Before the advent of the speakeasy, the ramshackle bar that sprung up and vanished as was required during the Prohibition era (and now turned a trendy locale for your friendly neighbourhood hipster), there was another hangout fast becoming everyone’s new favourite local in the mid 19th century – the temperance tea party.

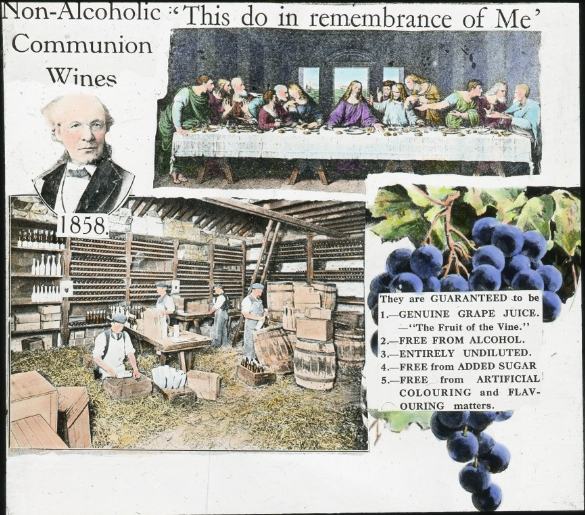

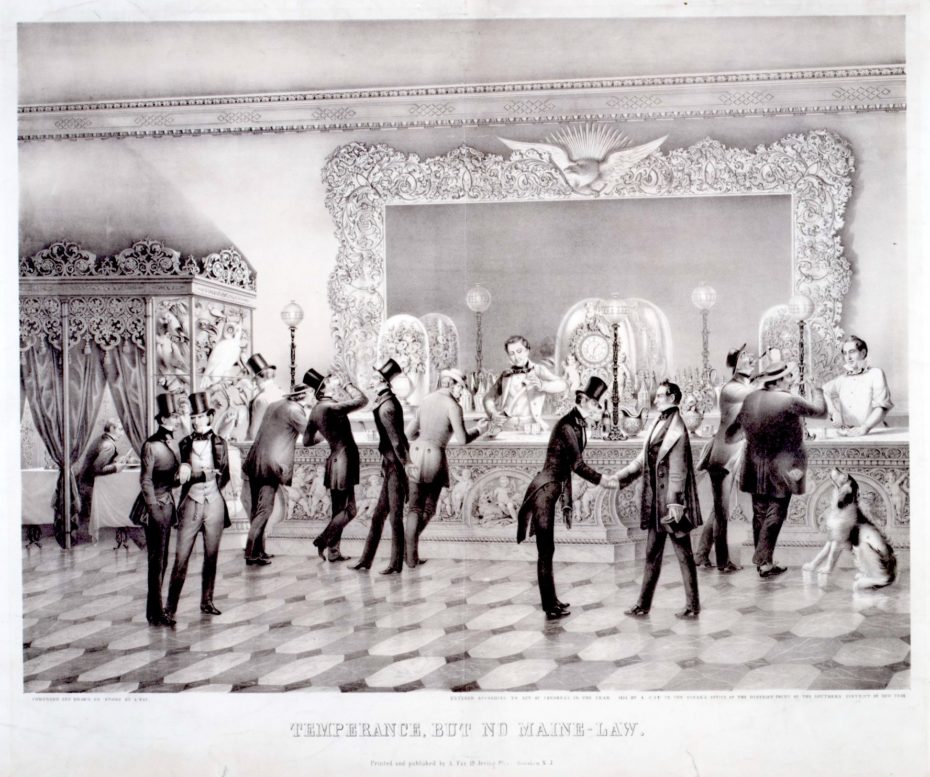

Held in so-called Temperance Halls, these large-scale tea parties were events designed to draw the workforce out of the gin palaces (a glorifed term for your local pub) and into more polite, moral, and sober society. But the gin palace had much humbler origins, once upon a time. A century earlier, most purveyors of gin were not actually in the business of selling alcohol, but selling medicine. They were in fact – and this is not a metaphor – chemists. Gin originally had medicinal associations and patrons bought it to take away, or drank it standing at the counter. It was this seemingly virtuous shop counter, over which crossed belladonna, cocaine, and everyone’s favourite asthma-inducing cigarettes, that led to the bar as we know it today.

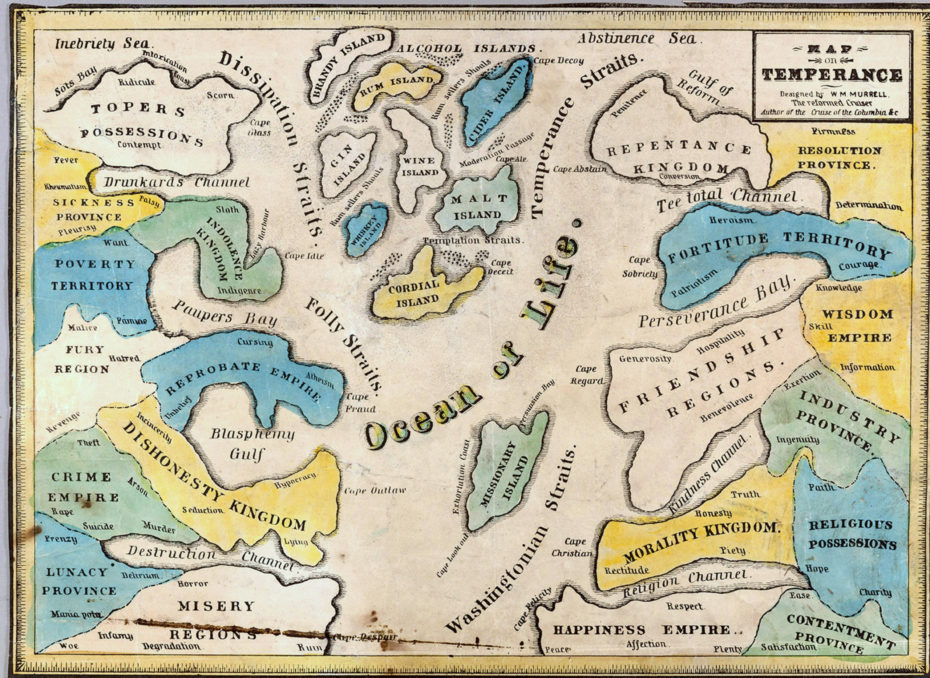

But why, a century later, was there such a strong desire to get people out of the gin palaces and in front of a teapot? Well, as the saying often goes, after a rather rough night out, we may have taken things a bit too far. Drinking gin, and other ‘medicinal spirits’, had gone beyond doctor’s orders and was becoming an outright epidemic, across both Britain and the United States.

This was due in part to the lack of access to clean and safe water for the poorest citizens, which meant many drank alcohol because it was cheaper than the alternatives. But it was also due to the fact that the late 18th century gave birth to the Industrial era, and this only spiralled further throughout the 19th. In short, the working classes worked for a living, and that work was poorly paid, poorly regulated, and pretty much miserable for everyone involved. The one thing they could look forward to at the end of a long day was the Victorian equivalent of cracking open a cold one.

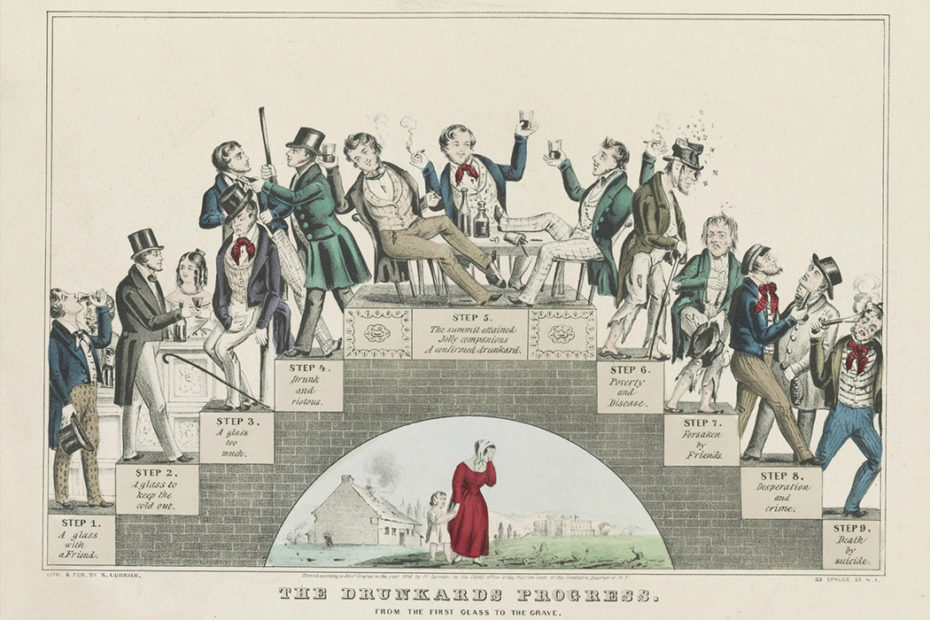

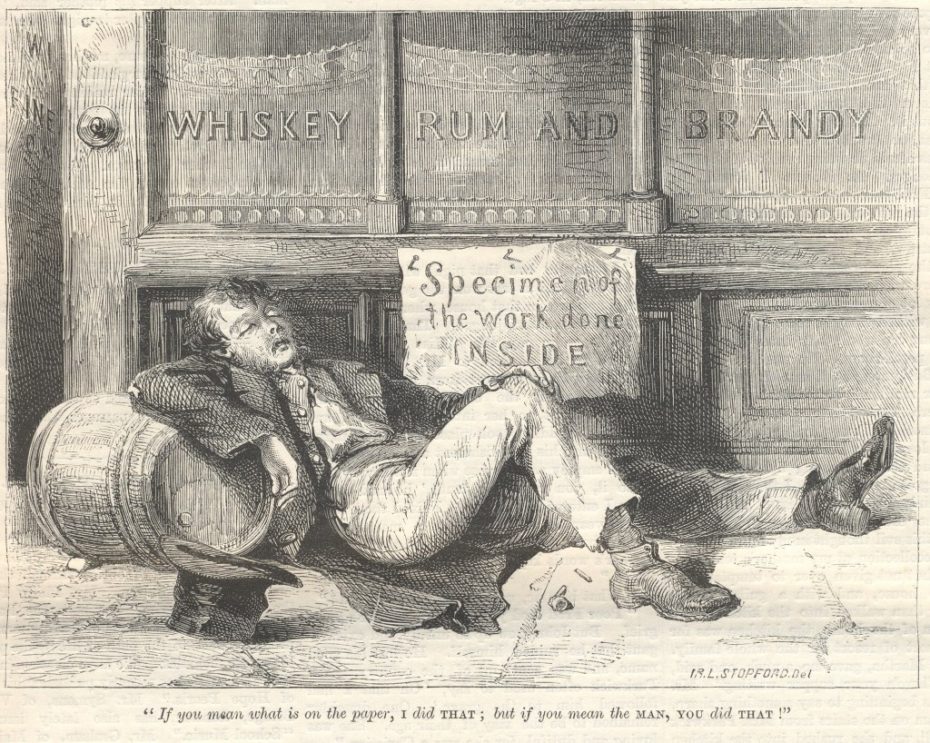

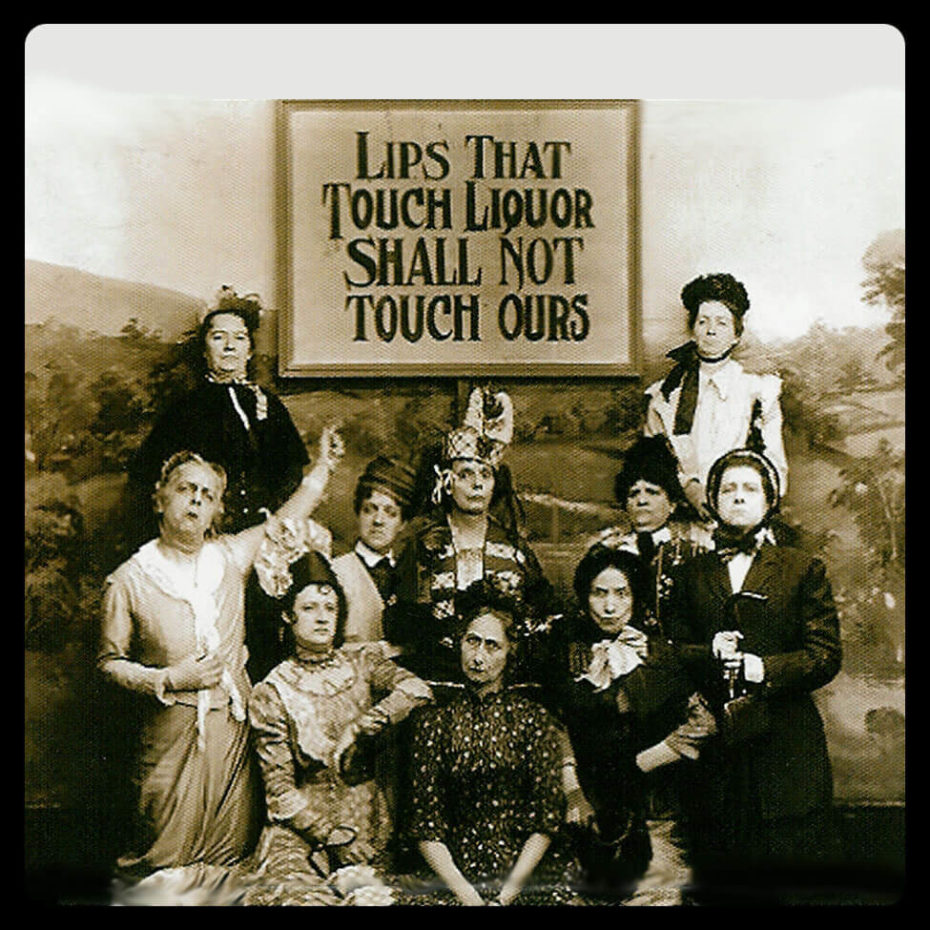

Life for the working classes were only getting more difficult as the industrial revolution fired up, and so further they spiralled into the ‘demon drink’. But this presented its own set of problems. Temperance societies set up by religious and women’s groups to help deal with these problems were largely concerned with the negative effects of alcoholism on the home; on the cohesion of the family unit. Domestic violence was rampant, children were starving from a lack of funds to buy food; funds that were being eaten up by the drinking dens that were all too happy to part fathers and husbands with their hard-earned coin.

But the kingpins of industry were far more concerned with something else. As can be found on the information packet of nearly all drugs purchased today, those under the influence are strongly advised ‘to avoid operating any heavy machinery.’ By far the biggest employer of the Industrial era was the cotton industry, which required the use of complex equipment and dexterous fingers. A drunk workforce was a sloppy workforce, and that wouldn’t do.

One of Britain’s earliest pioneers of the temperance movement, whose name is most associated it with it today, was a man by the name of Joseph Livesey. He lived and worked in Preston, a city in the county of Lancashire in the North West region of the United Kingdom. Preston, unsurprisingly, was a mecca of the Industrial era. Its skyline had long since lost its bucolic, verdant curves, trading them in for the dull, geometric spectres of the cotton mills. This was cotton country. They say that the city of Rome has more Egyptian obelisks than Egypt and, in the mid 19th century, Lancashire had more cotton mills than anywhere else on the planet. It was here in Preston that one could argue, began the entire industrialised world as we know it today.

Livesey wasn’t in the business of selling cotton, but selling cheese. His motivation for sobering up the nation wasn’t led by profit margins, but by a sense of philanthropy. Livesey was a hardliner for a total abstinence from alcohol, and established the Preston Temperance Society. It was this hardcore version of the temperance movement that became known as teetotalism.

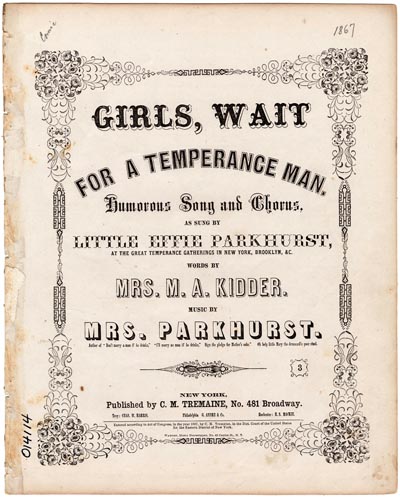

Temperance was slow to be taken up, to begin with, Teetotallers were given a bad rep as a miserable bunch of folks, and their propaganda could be a bit OTT. But as the 19th century ticked closer towards the turn of the 20th, being teetotal was on the rise. While it was all well and good that a large swathe of the local population had heeded his call for total abstinence, what were they to do now that they couldn’t (or shouldn’t) go down the pub for a quick one? And so, the British engineered the most British of solutions: the temperance tea party.

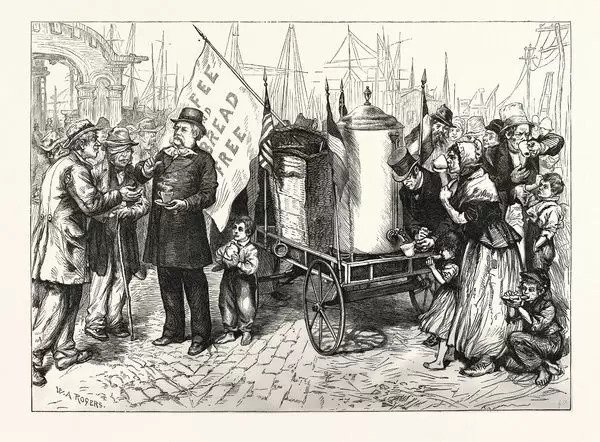

The goal of these tea parties, perhaps even more so than preventing people from turning to alcohol, was an intermingling of the classes. Prior to temperance, the social classes almost never mixed, and the act of drinking itself was considered a man’s endeavour. In this way, it wasn’t just an intermingling of the classes, but of the sexes – a novel idea for the period. And these tea parties were no quaint village hall affairs, they were spectacles. In 1832, over 500 Prestonians gathered around huge tea-urns and tables piled high with bread, cakes, and fresh fruit, all free of charge.

Historian Erika Rappaport writes that the temperance tea party, and the reformers who organised them, “implied that by drinking tea instead of alcohol, consumers would achieve class and gender harmony, political citizenship, and a heavenly home.” The parties became a kind of ritualised event, and the mass amounts of food a kind redemptive experience for those who took part. They even acted as a teetotaler’s 19th century “Tinder” for those looking for sober spouses.

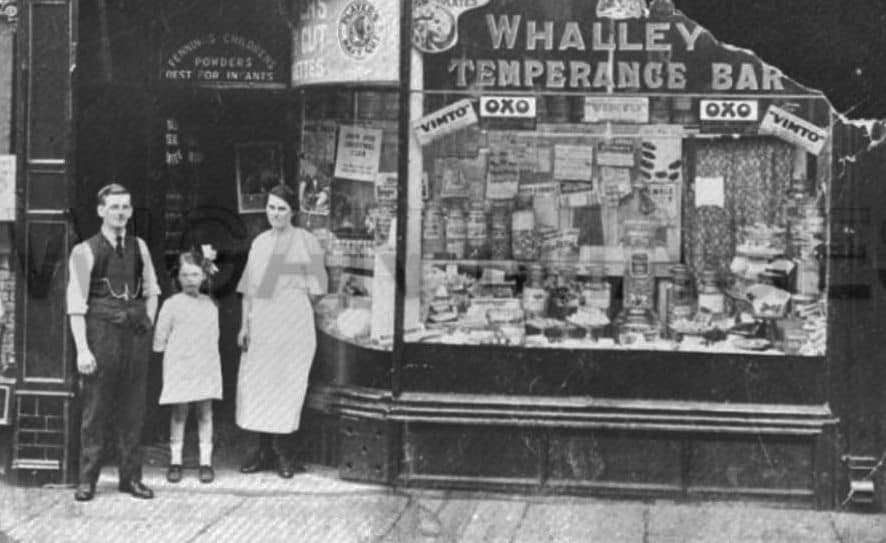

If tea parties weren’t your scene, there were other places in which to indulge your new sober lifestyle. Alongside temperance halls, many of which have became well-known theatres today, there were alcohol-free hotels, billiard rooms and temperance bars. Temperance bars were particularly popular in the North West, and were like your average gin palace; dimly lit, a vague smell of spilt drinks, only they didn’t serve alcohol. Instead, you could partake in some medicinal sasparilla, dandelion and burdoch, or blood tonic. Unlike normal bars, which took the man out of the home, temperance bars encouraged a multigenerational approach to spending your precious free time outside the factory.

Mr Fitzpatrick’s, in the northern mill town of Rawtenstall, opened in 1899 and is still serving the local sober population today, though it’s the last 19th century temperance bar of its kind. Atlas Obscura describes it as an “enchanting place, with shelves crammed full of herbs in towering glass jars. “Its menu still revolves around what was on offer more than a hundred years ago: 16 traditional botanical cordials concocted with herbs, fruit, and spices.

At its height, more than six million people in Britain were pledged teetotallers. By all accounts, when Joseph Livesey died at the ripe old age of 90 in 1884, he was a common folk hero, with thousands lining the streets of Preston for his funeral. But towards the mid 20th century, the temperance movement was on the wane. Temperance halls turned into theatres, and temperance bars started to disappear. The tea parties were no more, the emerging youth culture more absorbed with consumerism and rock ‘n’ roll than wholesome 19th century social movements. But that isn’t to say we all fell back into our cups. The 21st century has seen a large decline in the number of people consuming alcohol, especially amongst younger age demographics. While the pub was once the focal point of socialisation in Britain, some suggest that communicating online has ensured alcohol is no longer a significant factor in forging friendships for today’s Gen Z and late Millenials. The temperance bar isn’t quite dead yet, either. Modern takes, like Club Soda, are cropping up all over the place. And similar to the temperance movement itself, each year sees thousands – albeit temporarily – giving up the demon drink for initiatives like Dry January and Sober for October. A brief whiz around Wikipedia gives us a list of contemporary teetotallers, amongst them the late Steve Jobs, Tom Ford, Jennifer Lopez, Kim Kardashian and even, Donald Trump, so he says.