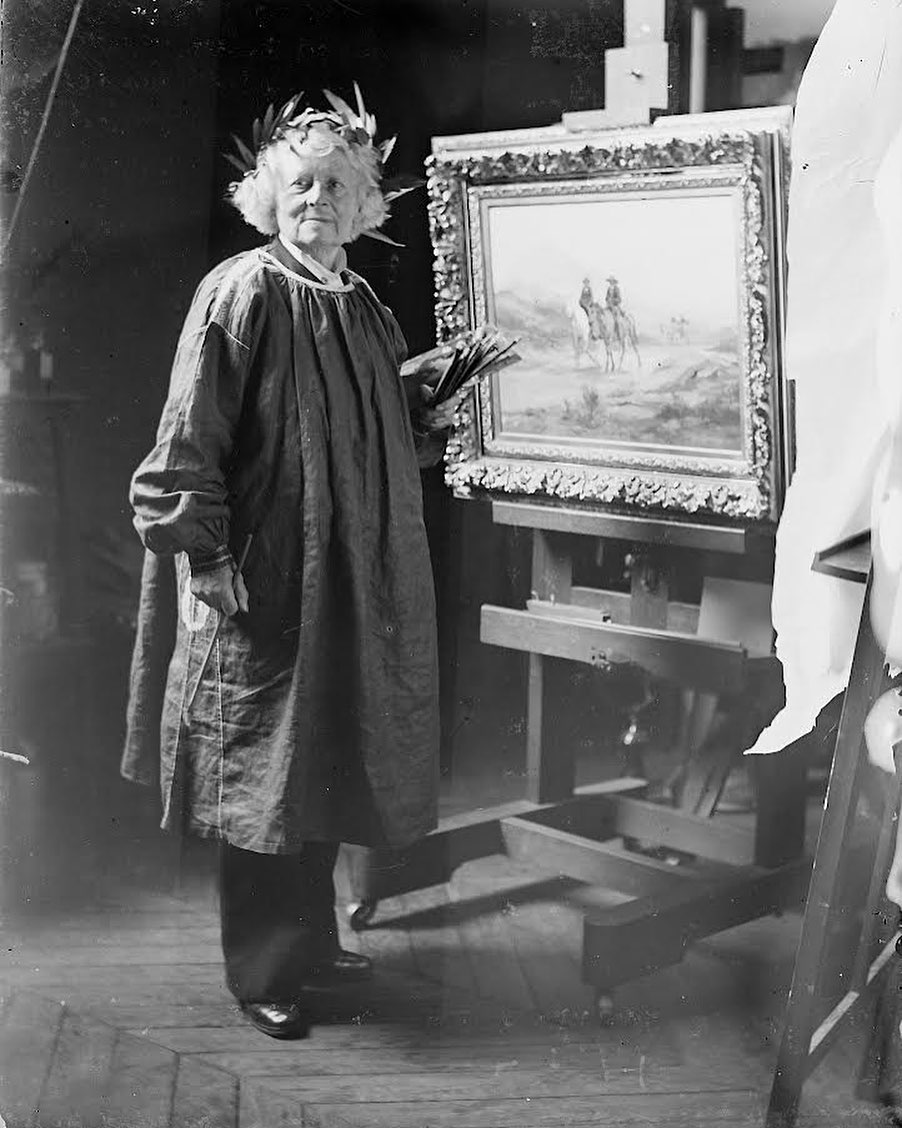

A cigarette-smoking, pants-wearing, animal-dissecting painter, Rosa Bonheur spent her life doing exactly as she pleased. 2022 marks the bicentenary of the birth an artist who opened countless doors for female creatives, both in her home country of France and abroad.

Born in 1822 in Bordeaux, Rosa Bonheur was the daughter of Sophie Marquis, a piano teacher, and Raymond Bonheur, a landscape painter. She grew up in a creative, progressive household, where she and her sisters were educated alongside their brothers. Many of the Bonheur children went on to become artists. The English sociologist Francis Galton mentioned the family in an essay about hereditary genius.

When Rosa was six years old, the Bonheurs moved north to Paris. She was a noisy, undisciplined child who was reportedly expelled from school multiple times. At the age of twelve, following a disastrous attempt at becoming a seamstress, she began training as a painter with her father. Sensing her potential as an animalier, he brought live animals into the studio and encouraged her to draw and paint them.

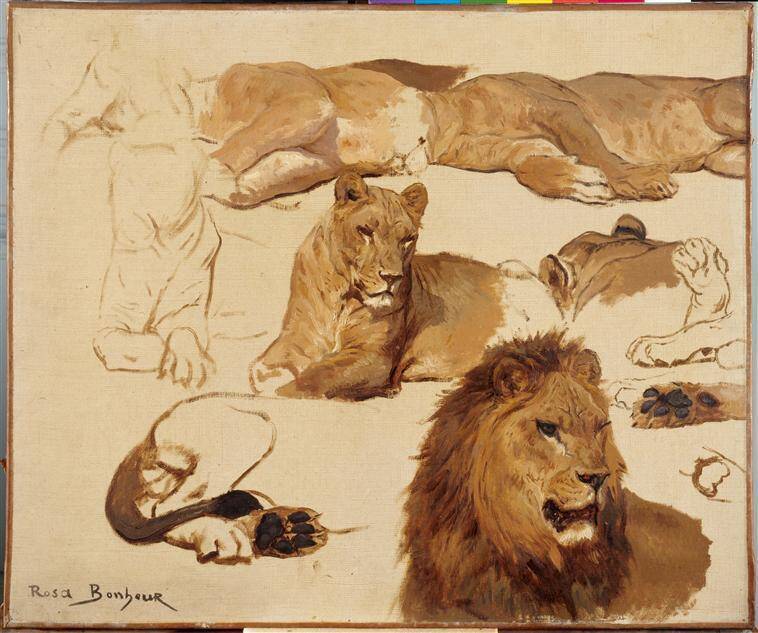

Bonheur advanced quickly. Her first work was accepted to the Salon of 1841, when Bonheur was just 19. She continued to be passionate about depicting animals. For all the time she spent copying the old masters in the Louvre, she spent even more escaping to the countryside in search of animals to sketch. A classicist at heart, Bonheur studied anatomy and even dissected animals in order to depict them as accurately as possible.

Bonheur’s artistic education was unusual for the time. This was largely thanks to her family’s liberal values and her father’s occupation as an artist. Raymond Bonheur had been the director of a school started in 1803 to instruct women in the arts. Upon his death in 1849 Bonheur took over the role. “Follow my advice and I’ll make you Leonard de Vinci in petticoats”, her students remembered her saying.

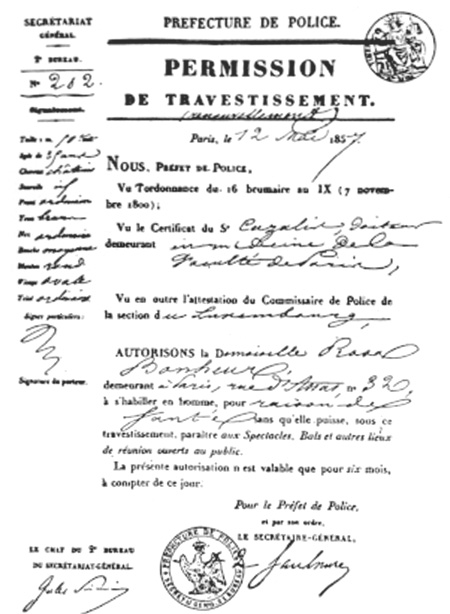

Speaking of petticoats. One of the most notable things about Bonheur was her love of wearing pants, a reflection of her personal style as well as her status as a woman who rode horses, visited livestock fairs, and painted on a daily basis, all activities that would be hindered by wearing heavy skirts. She held a permission de travestissement, effectively a legal document from the French government which had to be renewed every six months, allowing her to “cross-dress”.

Rosa Bonheur’s permission de travestissement

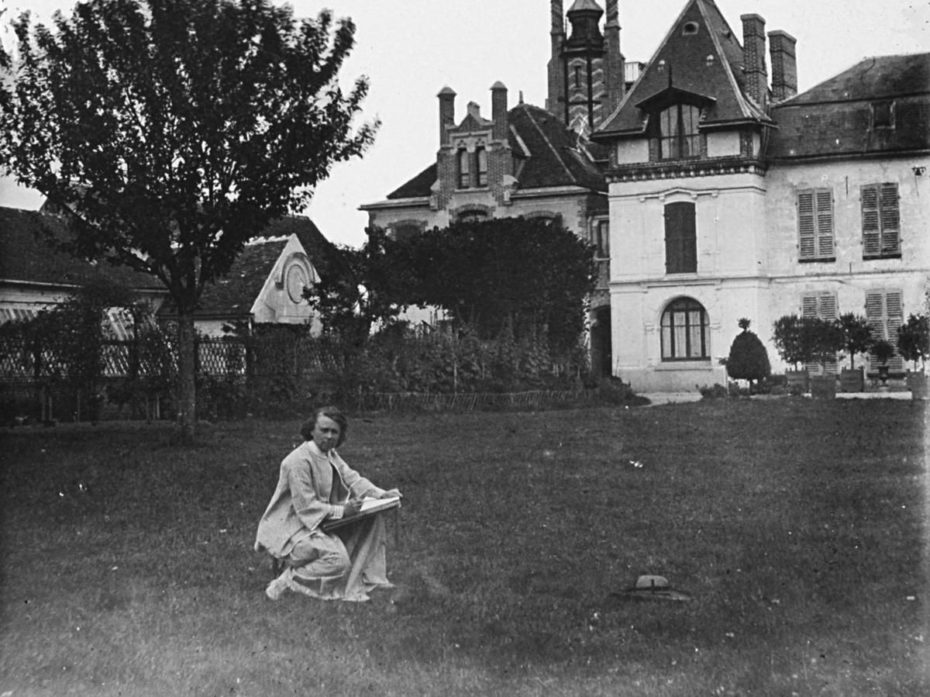

Rosa took full advantage of the permissions granted by creating something of a trouser-based uniform for herself while she worked. According to the archivist at Château de Rosa Bonheur, it was only really when she posed for the occasional portrait that she’d wear a dress. Not-so-fun fact: Until January 31st of 2013, it was illegal for women in France to wear trousers. It made headlines at the time when the 200 year-old law requiring women to ask police for special permission to “dress as men” or else risk being taken into custody, was finally revoked.

Soon Bonheur’s paintings became highly sought-after. Her monumental painting The Horse Fair, which she described as her personal “Parthenon frieze”, toured Europe and America, earning her international fame. The work was eventually sold to Cornelius Vanderbilt who later donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. French critics mourned the loss of what was already considered a national artistic treasure. Rumour has it, Napoleon III tried to buy it back, for a sum that Bonheur said was too low.

Vanderbilt’s acquisition of The Horse Fair showed the appreciation American patrons had for Bonheur. This affection was mutual, as Bonheur herself had a passion for America, especially the aesthetic of the wild west. She was particularly fascinated by Native American art and culture. During the 1889 Exposition Universelle, Bonheur met the mythic Colonel William F. Cody (AKA Buffalo Bill) who was in town with his traveling show. After watching many of his performances, she invited him to stay at her home. They hunted wild boar together and Bonheur painted his portrait. In return he gave her a traditional Sioux garment. The two stayed close for years. Later, when Cody’s house was burning down, he refused to leave without his friends painting.

After The Horse Fair, Bonheur was world renowned as one of the best living animalièr. She was given the honor to submit any work she wanted to the Salon, she received commissions from the French government, and she held an exhibit at the 1893 World’s Far in Chicago. She even had an audience with Queen Victoria. The highpoint of her fame came in 1865 when she was awarded the prestigious Légion d’honneur. The red ribbon adorned almost all of her jackets and became an essential feature of her “uniform”. In accepting, Bonheur became the ninth woman to receive the order of merit and the first female artist to be honored.

From the success of her work, Bonheur bought the Chateau de By, a castle where she set up an enormous studio as well as a fully stocked menagerie. “ a lion and lioness, a stag, a wild sheep, a gazelle, horses, etc. One of her pets was a young lion whom she allowed to run about” a friend relayed in a letter.

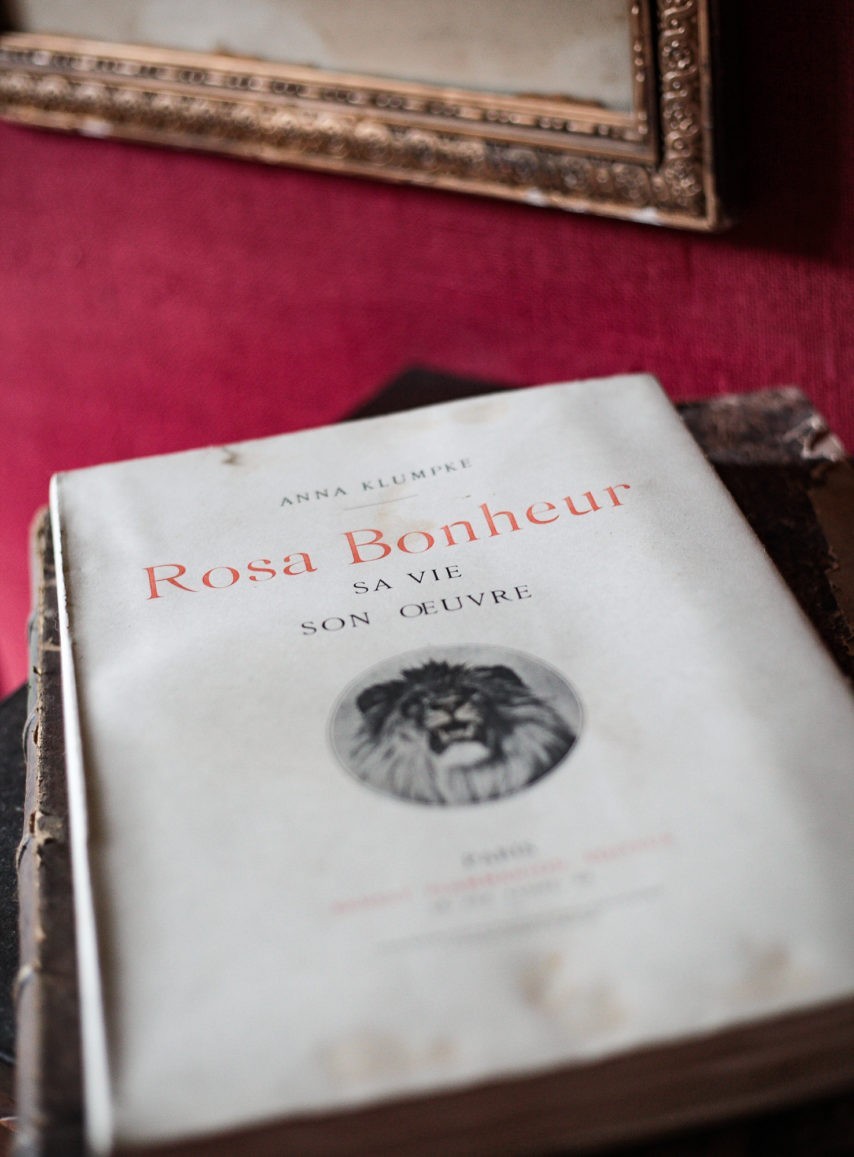

Despite never marrying or having children, the artist is believed to have been in two significant relationships. The first was with her childhood friend, Nathalie Micas. The two were inseparable for 40 years, until Nathalie’s death, after which Rosa met a younger American painter, Anna Klumpke.

Bonheur lived at the chateau du By until her death and is buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris. She influenced countless artists in her own time, including the impressionists, who appreciated Bonheur’s honest depiction of the natural world. She continued to inspire artists in the twenty-first-century, including Molly Luce, who cited first seeingThe Horse Fair as a pivotal moment in her artistic education, and the wonderful Wayne Thiebaud.

To celebrate Madame Bonheur’s 200th birthday this summer, head to the Parisian guingettes (village balls) named in her honour, or stay overnight at her Chateau, a time capsule waiting to be discovered.