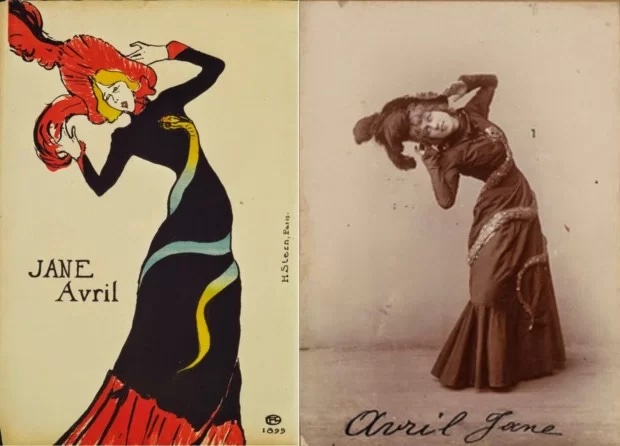

If you knew that “Satine”, Baz Luhrmann’s lead character in his 2001 movie musical Moulin Rouge! was in fact based on a real-life French can-can dancer called Jane Avril, the decision to cast Nicole Kidman might make even more sense. Avril, with her flaming red hair, thin lips and delicate facial features, tall gaunt physique and long, unmistakeable kicking limbs captured over and over again in Toulouse-Lautrec’s iconic posters, was once upon a time, a star in her own right. Paris in the 19th century: Montmartre was an intoxicating central cesspit for a creative explosion, and at the heart of it was that bohemian palace of pleasure, the Moulin Rouge. You could say that it was a haven to Jane Avril, who thrived in this Belle Epoque underworld, having escaped an even darker one. It was there, under the spinning red sails of the cabaret’s windmill that she would cross paths with her unlikely soulmate, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and become his muse. Their troubles were their bond: Jane Avril the delicate and damaged dancer, and Henri, the talented ousted aristocrat, both caught in an inescapable vortex of cruelty and creativity.

Born Jeanne-Louise Beaudon, Avril’s mother was a prostitute and she believed her father to be an Italian marquis who had abandoned them when she was only 2 years old. She was spirited off to a countryside convent by her grandparents in order to escape her mother’s dire influence. As fate would have it, her mother returned her to Paris in 1877 where Jeanne attempted numerous escapes from her mother’s control and eventually at the age of 14, was given refuge at the forbidding Salpêtrière Asylum, a mental institution for women in Paris.

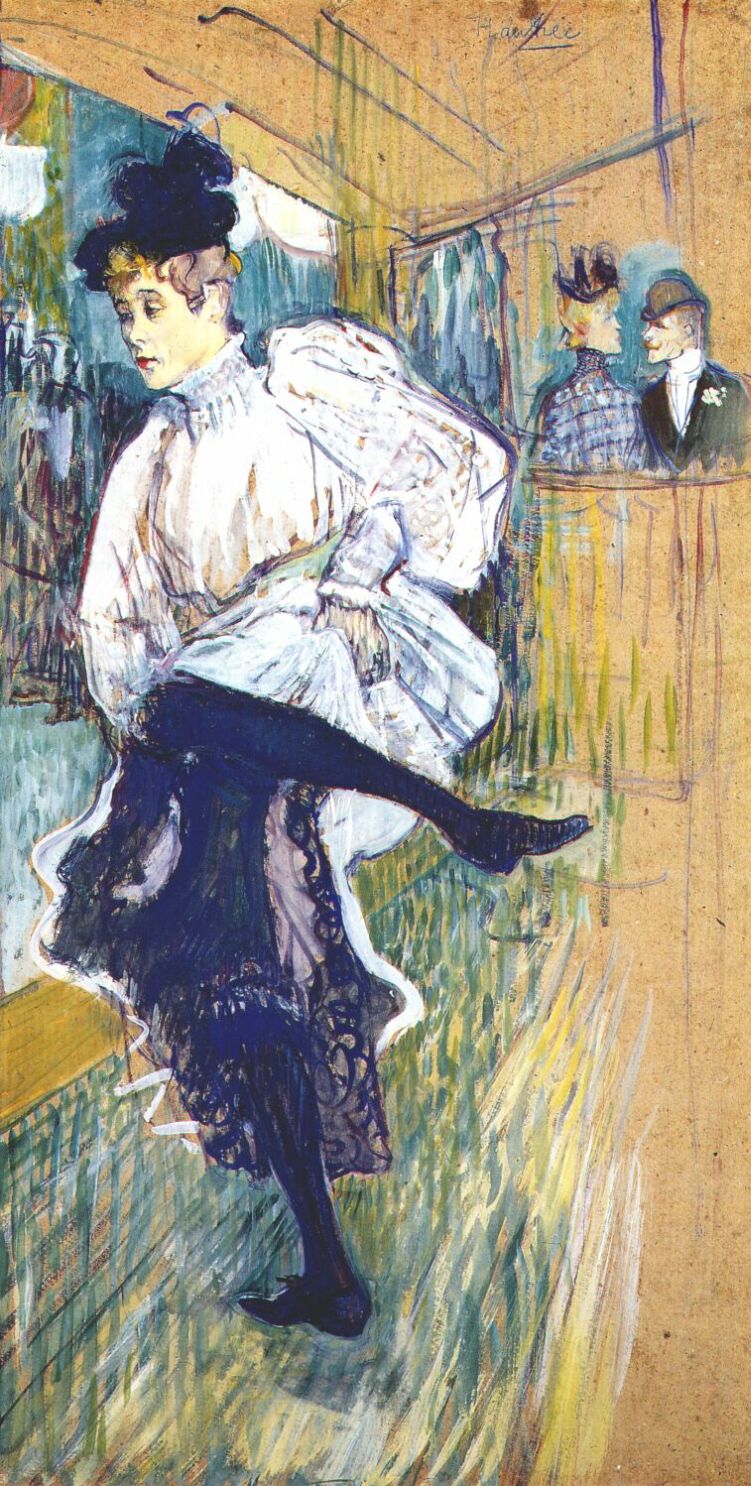

Within the sanctuary of the Salpêtrière Asylum, Jeanne was diagnosed with a neurotic condition, regarded at the time as a ‘female hysteria’. This was a physical affliction which produced sudden and erratic twitching and thrashing movements of her limbs. There was little understanding of such conditions at the time, far less any known ‘cures’. Fatefully, the institution, perhaps to satisfy the voyeuristic afflictions of its patrons’ fascination with abnormal human conditions, regularly held open day events for governors, staff and patients, known as Le Bal des Folles (‘The Ball of the Mad’). Jeanne soon discovered that dancing was not only therapeutic and aided her condition, but that she was able to move in ways like no other dancer could. Belgian born Parisian architect, author and critic Frantz Jourdain later described her as ‘this exquisite creature, nervous and neurotic, a captivating flower of artistic corruption and sickly grace”.

Upon Jeanne’s release from Salpêtrière in 1884, seeking shelter, she fought her way from club to club, eventually landing at Le Chat Noir, then a new and already infamous cabaret club in bohemian Montmartre. She immersed herself in dance and performance, engaging with patrons like Oscar Wilde and Stéphane Mallarmé. It was at Le Chat Noir that she met Robert Sherard, Oscar Wilde’s first biographer, who suggested she adopt the more exotic and Anglophile stage name ‘Jane Avril’, which would serve to conceal her identity on stage and also from her still preying mother.

Jane’s routines were so unusual and mesmerising, she attracted outlandish headliner titles such as as L’etrange (‘The Strange One’), Jane La Folle (‘Crazy Jane’) and La Melinite (after the explosive). Jane danced at many venues, notably the Latin Quarter’s Le Jardin Bullier ballroom.

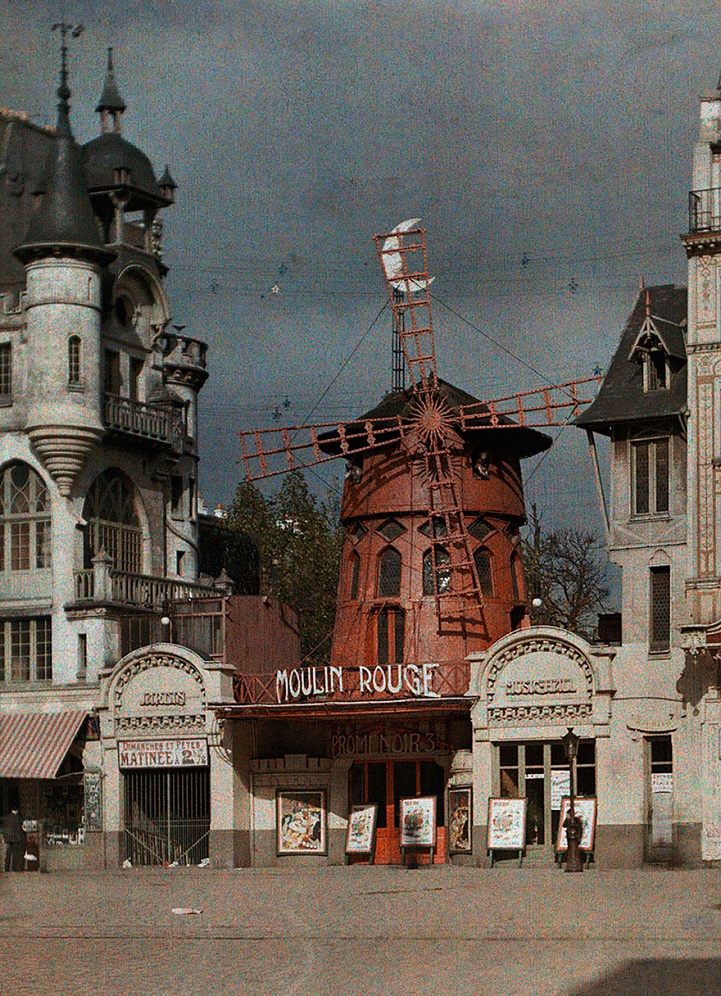

In 1889, Charles Joseph Zidler, co-founder of the Moulin Rouge Cabaret Club employed Jane Avril as the club’s new headline act. Jane replaced the cabaret’s fallen Queen, legendary dancer Louise Weber, better known as La Goulue (‘The Glutton’). La Goulue had pioneered the exotic Can-can dance with its endless display of layers of white petticoats.

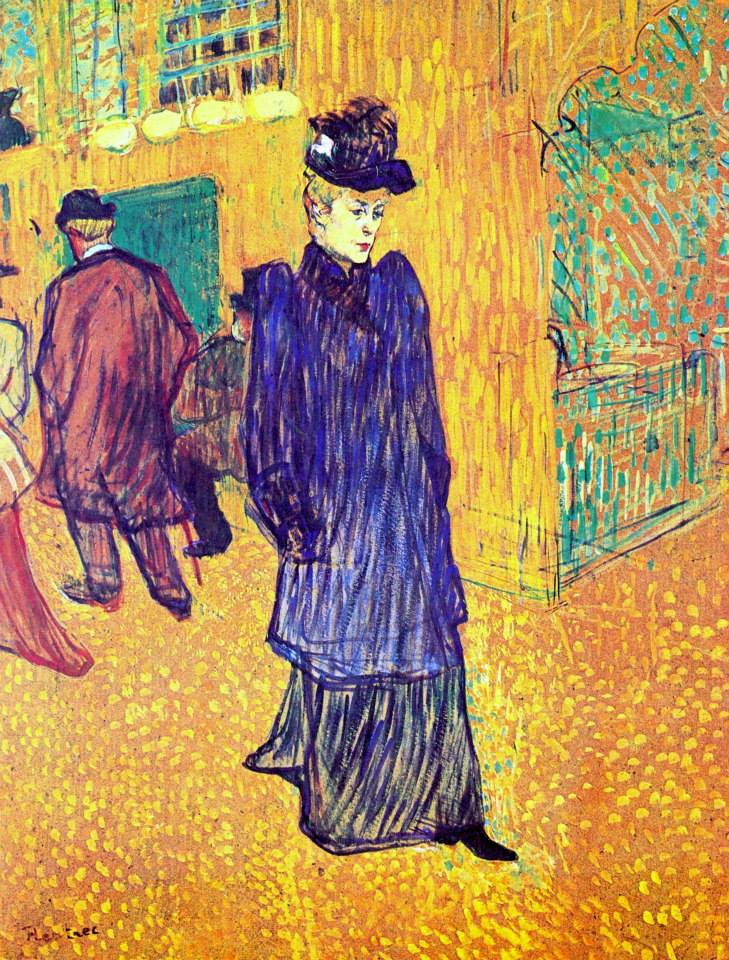

Jane Avril would bring something new, delicate and demure to the stage with her strange, reflexive sudden bursts of motion. Her hypnotic dance routines were described as ‘an orchid in a frenzy’.

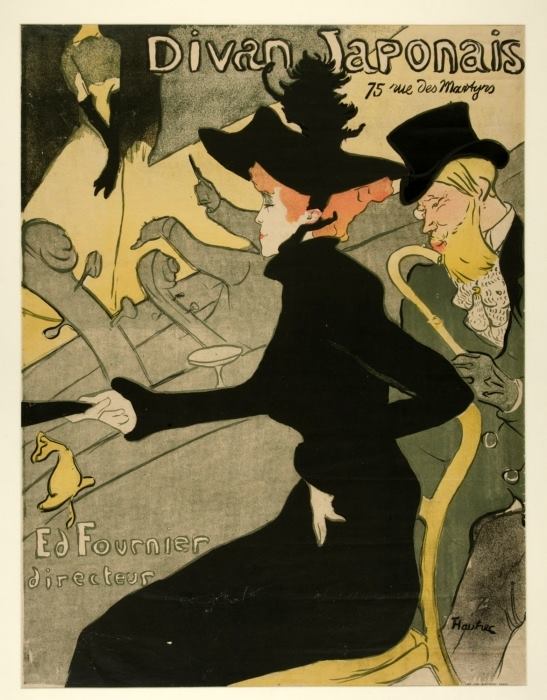

Jane Avril would dance in many of Paris’ legendary venues through Zidler’s patronage, with Jane choregraphing her own routines and designing her own costumes. In 1893, she prepared for another of Zidler’s grand balls, the ‘Jardin de Paris’ held on the Champs Elysées. To promote this spectacular event, Zidler instructed his radical poster artist from the Moulin Rouge, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Jane and Henri would be inextricably linked forever.

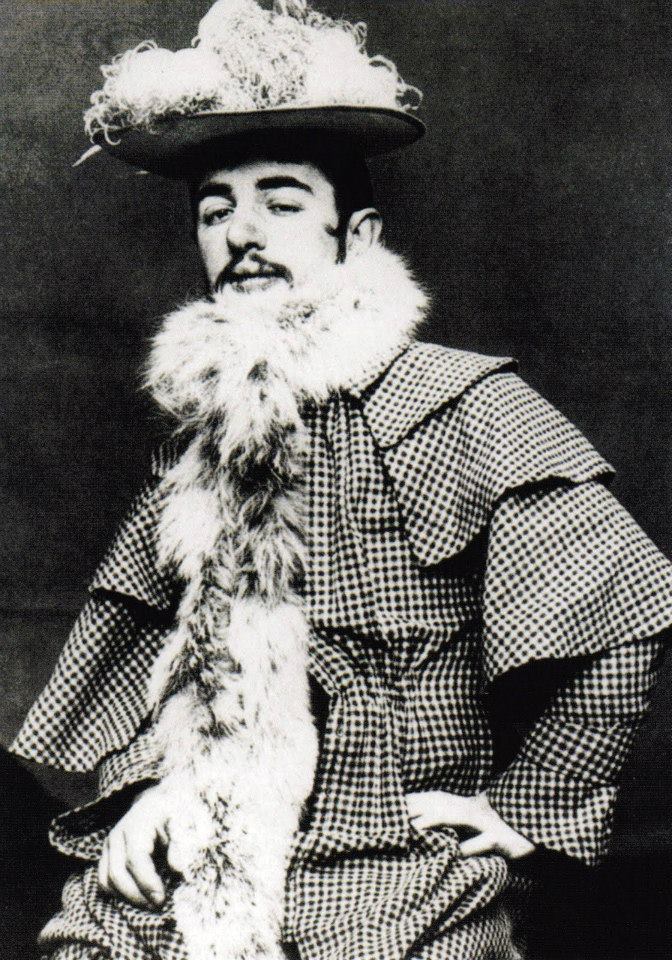

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa was born into an aristocratic land-owning dynasty. Should he have outlived his father, he would have been titled the Compte de Toulouse-Lautrec. Unfortunately, Henri was born with a genetic disorder, pycnodysostosis (‘stone bones’), where bones became dense rather than long. As a result, Henri’s legs would never fully develop and to boot, his condition was aggravated by several riding accidents in his teens. Unable to participate in traditional boyhood play, he concentrated on drawing and painting. His early work featured horses, but as he entered adulthood, he was captivated by Parisian night life and became intoxicated with the struggle and strife of life in the debauched drinking dens, dance halls and brothels of the underclasses.

The darkened, narrow streets of Montmartre’s nights were his world. Like the broken dancers and the hardened prostitutes, Henri was equally a misfit, an aristocrat cut off from his kind, a lost dog easily tethered into this edgy world of the imperfect. Accepted by these unusual families of the ladies of the night, Henri would enjoy their confidence and co-operation, permitted to draw and paint them in their most intimate and private routines; dressing, bathing and loving. Henri was bewitched by them.

Henri said of his subjects “A model is always a stuffed doll, but these women are alive. I wouldn’t venture to pay them the hundred sous (coins) to sit for me, and god knows whether they would be worth it. They stretch out on the sofas like animals, make no demand and they are not in the least bit conceited.” He was fully accepted by the ladies, and rejoiced, “I have found girls of my own size! Nowhere else do I feel so much at home”.

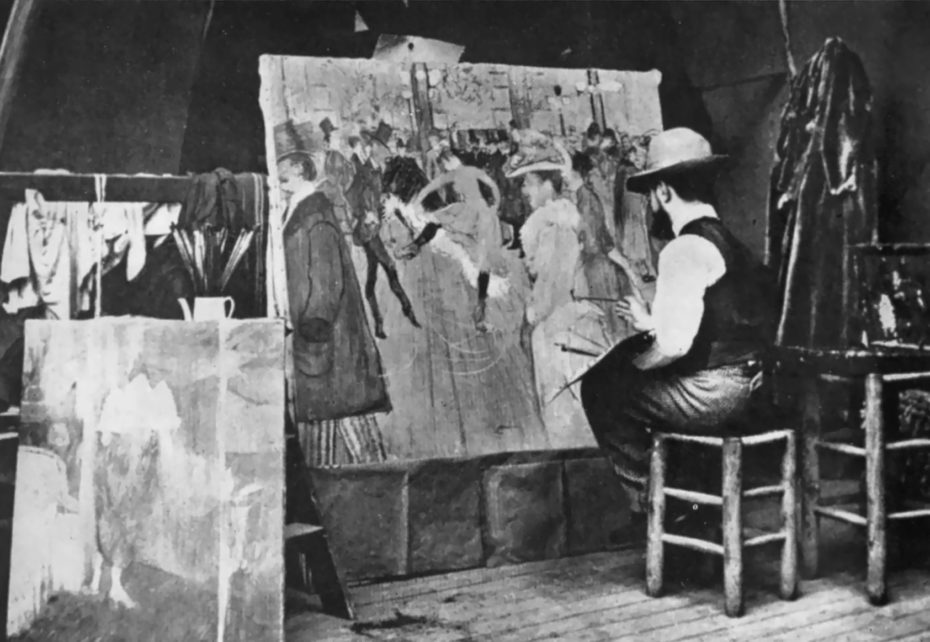

The first Moulin Rouge (‘The Red Mill’) cabaret club stood in the north of Montmartre, its infamous blood red windmill sails flying above on the street front. The club had opened in 1889 and Henri was commissioned in 1891 to produce publicity posters to promote the regular evening events and acts. Although the public loved his posters, Henri’s work was not regarded as ‘art’ by his peers in Montmartre, however, the club was a good gallery to promote his posters and paintings.

Jane Avril had started dancing at the Moulin Rouge in 1889. While publicly, she was most certainly his painterly muse and inspiration, in private she was an enduring friend to Henri Toulouse Lautrec. Henri obsessively produced posters, sketches and paintings of Jane until his untimely death in 1901. He would capture almost all aspects of Jane’s life in his posters of her dancing, in the sketches of her arriving at stage doors and in his formal sitting portraits of her. Jane may well have been Henri’s obsession, but she had an endless series of suitors and admirers.

And she certainly had her fair share of passionate affairs with fellow female dancers, May Milford for one, who Henri also painted in his posters. At 42, Jane married French artist Maurice Biais, another cabaret poster artist, who had also worked promoting her on behalf of Zigler. The Moulin Rouge’s first incarnation came to end with a devastating fire in 1915. The Great Depression which soon followed, lead to her bankruptcy as a widow and she died in 1943, like she began, in obscurity and poverty.

With only photographs and Toulouse-Lautrec’s art to go by, we’ll never know the strange beauty of Avril Jane’s dancing. Despite being the literal poster child of the Moulin Rouge, her legacy has been largely forgotten, and much like Satine, the fictional character she inspired, her legacy is rather tragic. “The facial expression is one of incredible sadness. Of one of Lautrec’s most intimate portraits of Avril, one contemporary described the mood: “One feels the weariness, one sees that the young woman dances for our pleasures and not for hers, one reads it as the poorly hidden desire to escape from this existence where the blasé public takes too much.”