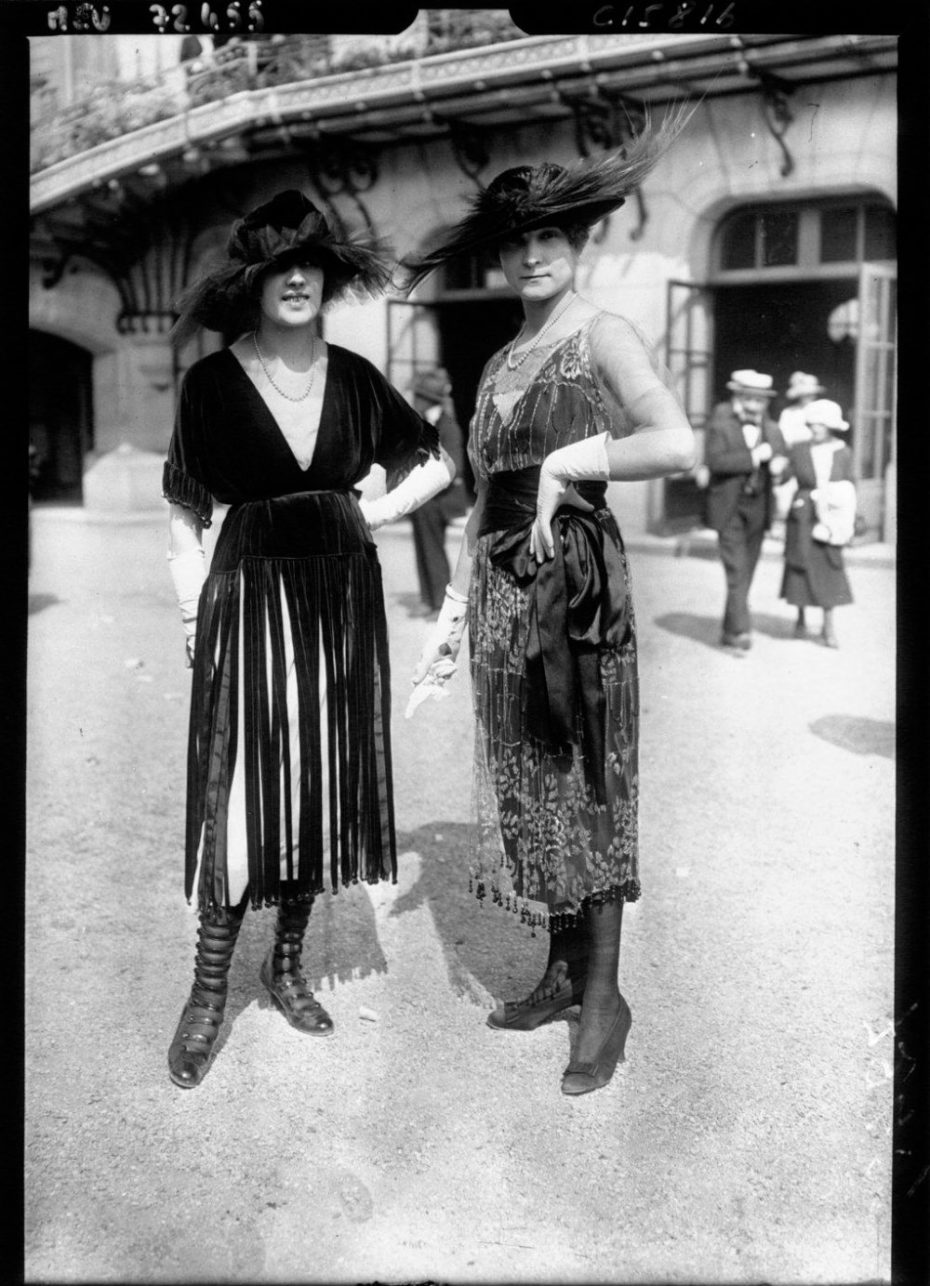

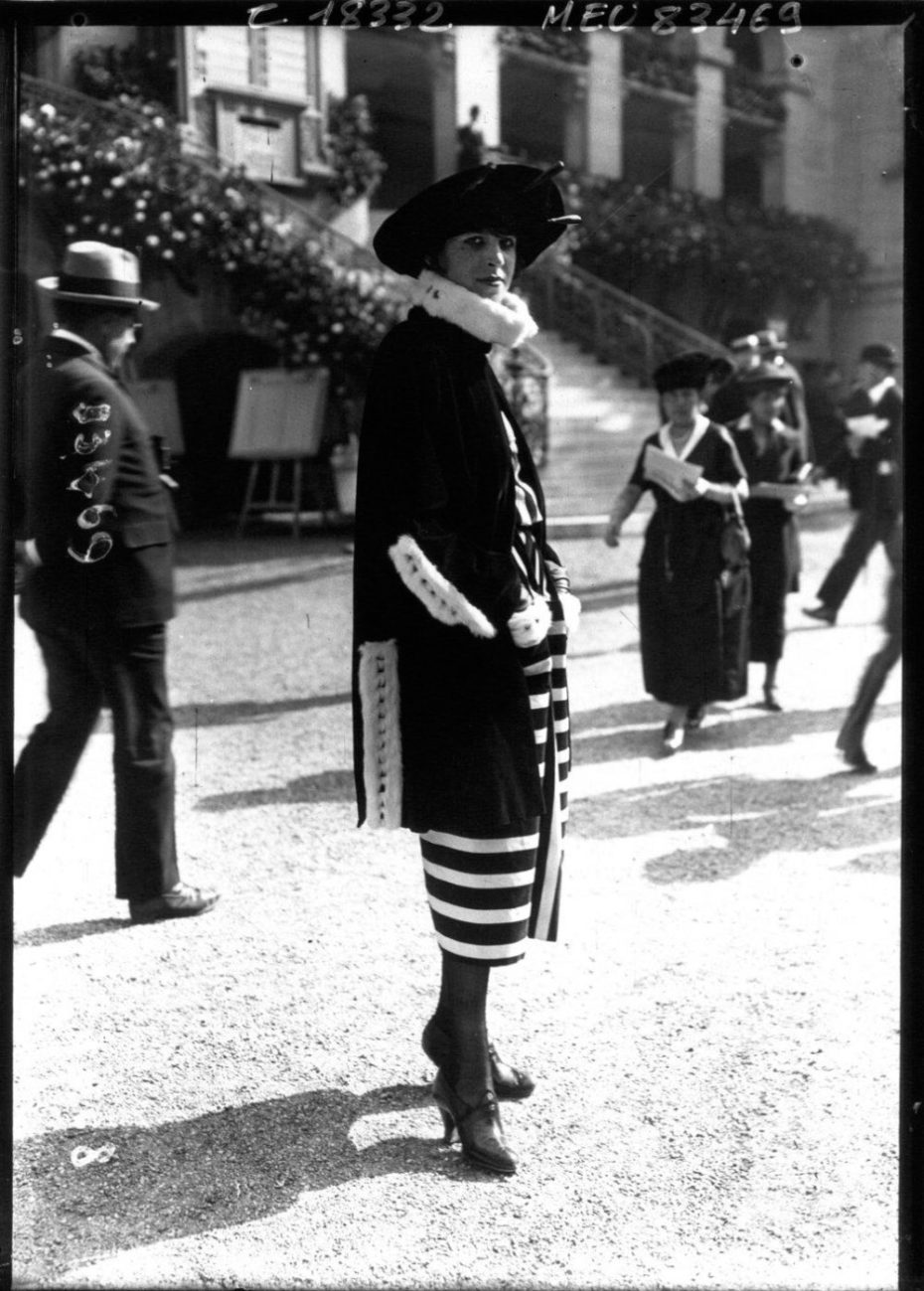

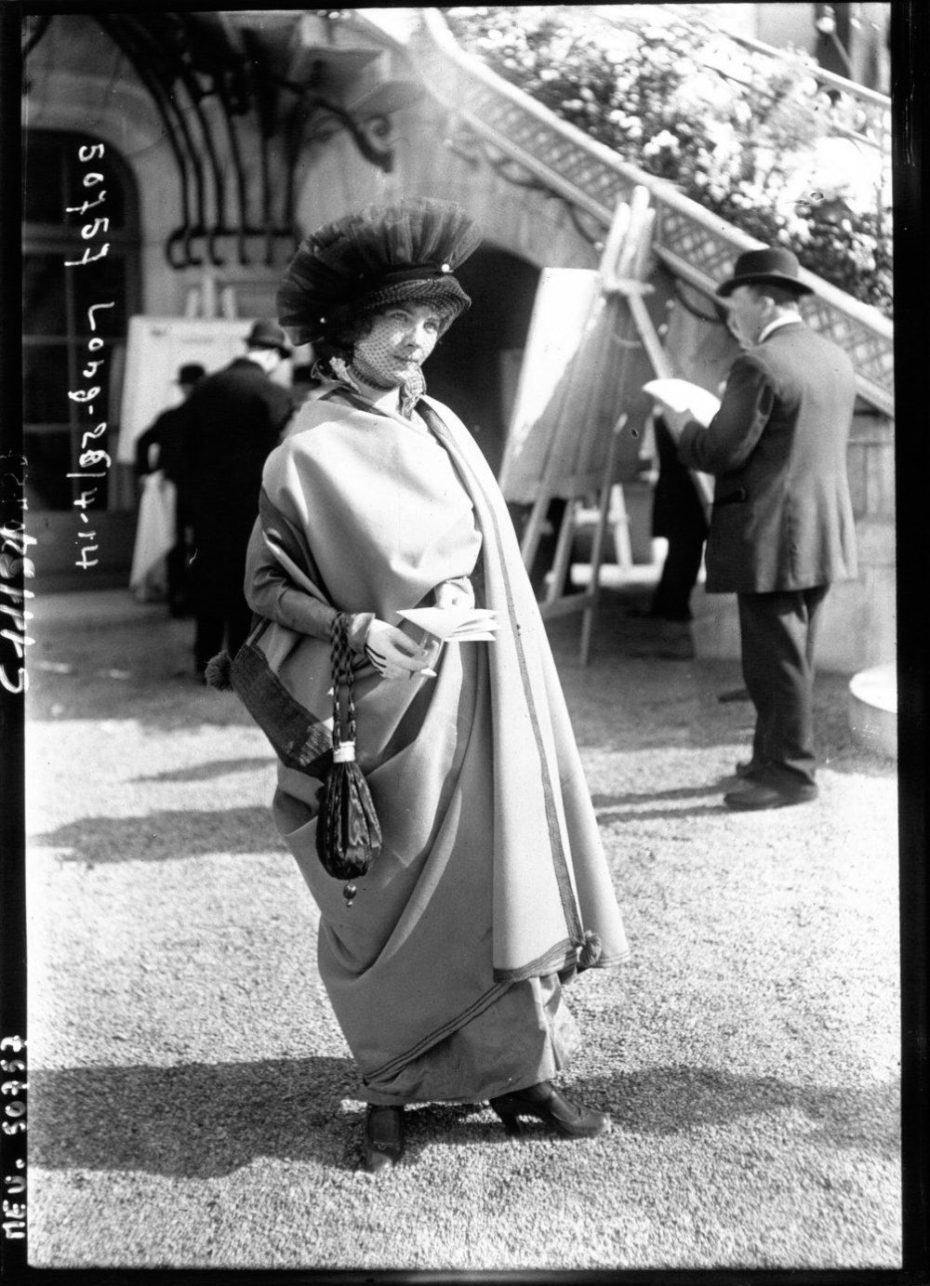

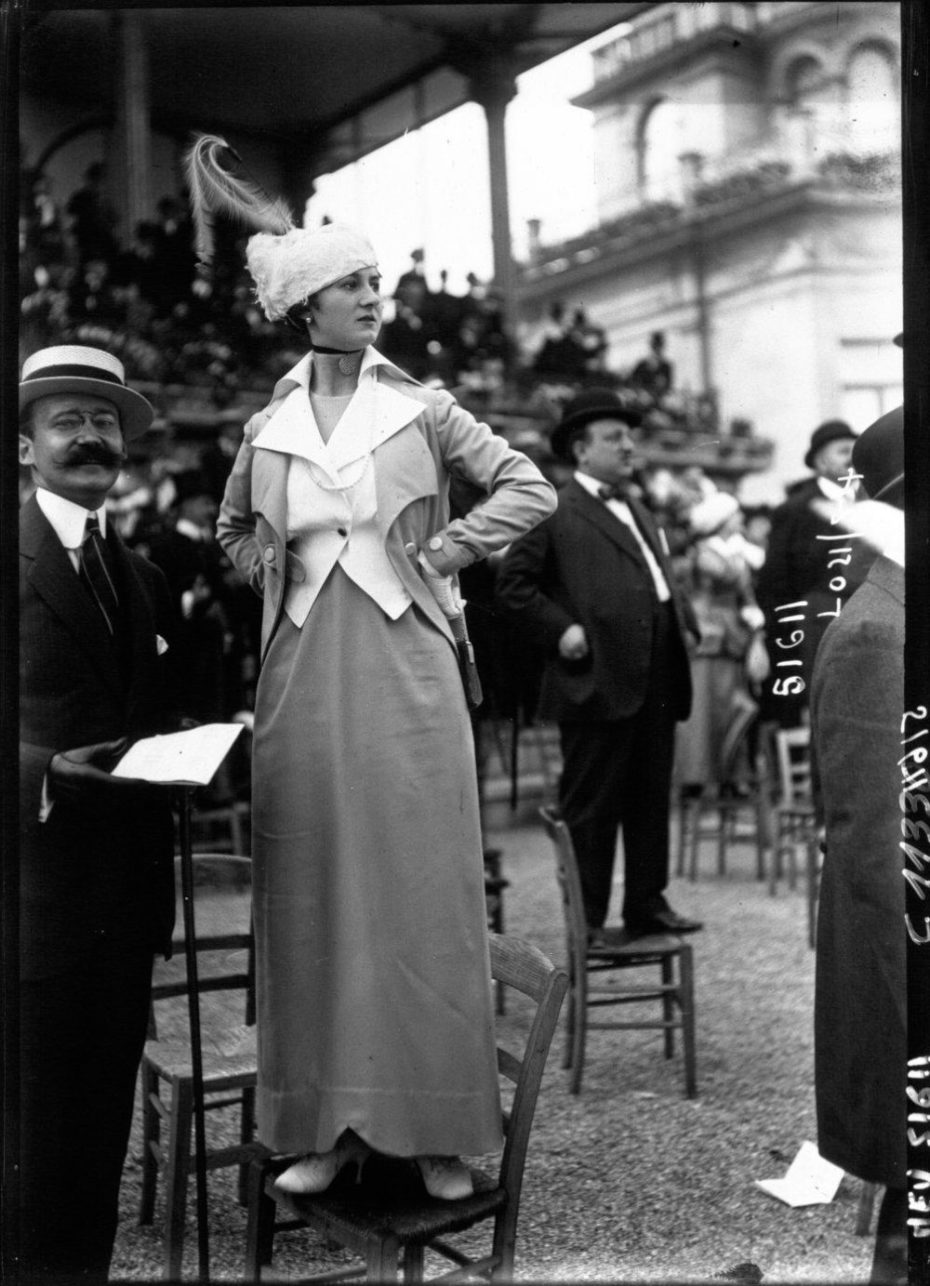

In the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century, spectating at the races was a glamorous event beyond comparison. Paris’ Hippodrome de Longchamp racecourse was the place to see and be seen; it was a stage where the bold and the beautiful would strut their perfectly tailored, coiffed and manicured stuff for all to marvel at from beneath their lace parasols. The sophisticated French capitol was hands down the centre of the fashion universe. Its boulevards and grand department stores, its opera house and even the morgue (yes, you read that right) were the scenes of stylish displays of incomparable proportions. But there was arguably no greater stage than the Parisian racetrack. It didn’t take long for the city’s scores of enterprising haute couturiers lining the Rue de la Paix to clock that Longchamp, held every Spring from 1863 onwards, complete with a select cross-section of the fashion-conscious Parisian society, was the most extraordinary runway; the most perfect paddock for piloting their nouvelle mode pageantry. The fashion houses would send out their own choice clothes horses, dressed in their very latest creations to rub shoulders with the bourgeoisie. The race – and fashion fever – was indeed on, and all the rivalrous haute couture thoroughbreds were vying for a first place and some publicity – good or bad. This spectacle, only a few minutes from the Eiffel Tower would have been attended by the likes of Napoleon III and the excitement was vividly captured in many of Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas’ paintings.

From the early morning on race day, fashionable Parisians would be proceeding along the Champs-Elysées in their carriages towards Longchamp, where huge crowds of all ranks and classes would steadily be gathering and mingling. The royal couple, aristocrats, government officials and other well-heeled high society members would be ensconced in their special enclosures, while the bourgeoisie and the lower-classes would be seated on the grass.

After the races finished, the highly anticipated gala balls were not to be missed, and for many, were an important opportunity to climb social rank via their style. And one didn’t just casually show up to Longchamp in their favourite frock from last season – according to historian John Potvin, such a faux-pas was a serious risk from a social standpoint at a time when so much depended upon appearance. “One needed to invest in articles of clothing in order to gain access to privileged spaces.”

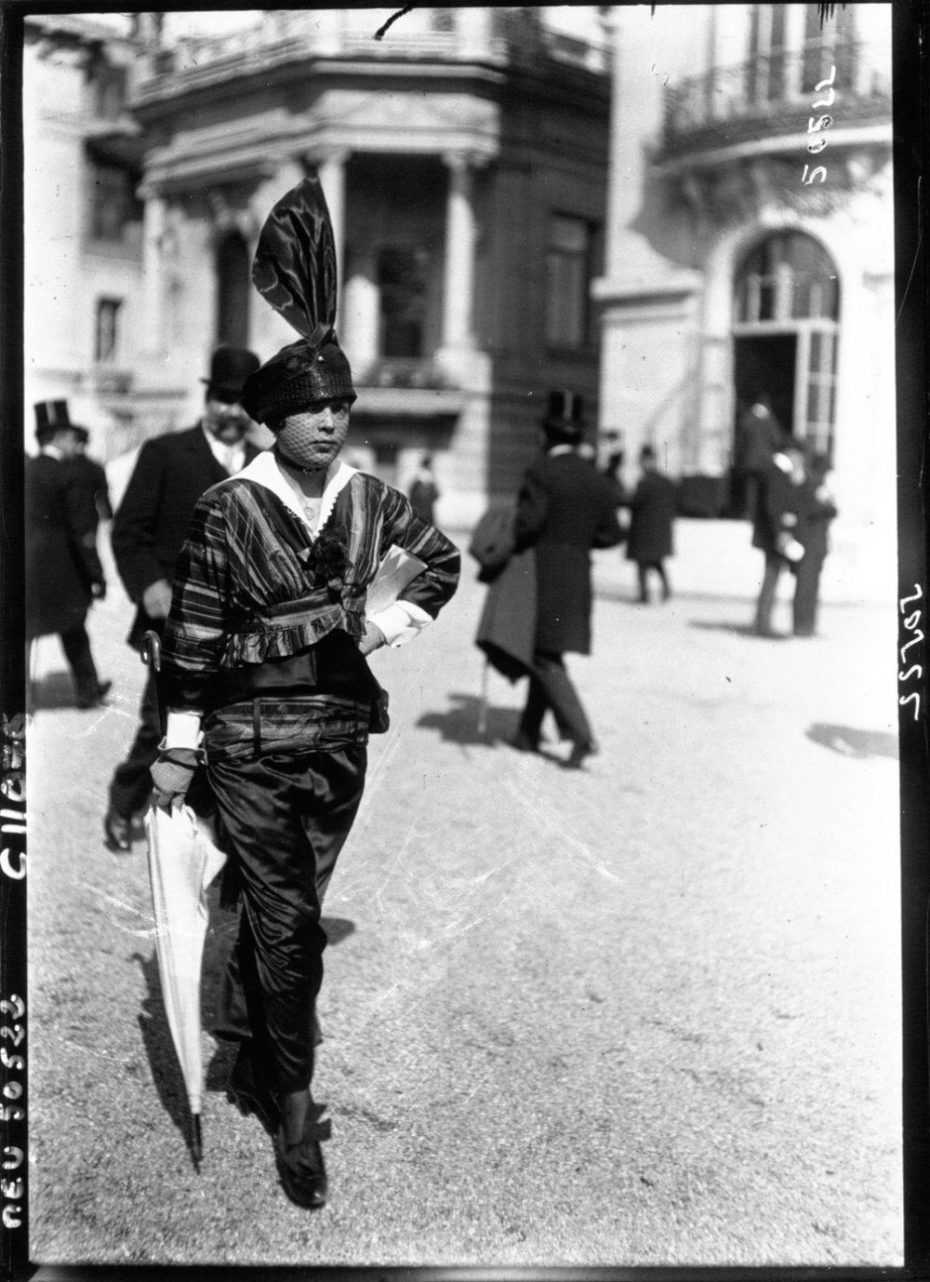

Some attendees to Longchamp were ladies who weren’t necessarily accompanied by a gentleman – as was the custom for the upper classes. This new genre of celebrity were the famous demimonde, women who hovered inconspicuously on the fringes of respectable society. They were tarred with the brush of somewhat doubtful social standing and dubious morals. And scandalously, they were more often than not kept in style – and high fashion – by their well-to-do lovers. But who were these celebrity mannequins and their high fashion couturiers? Paris Haute couture at the time was dominated by the influential Charles Worth who turned high fashion into a booming industry. His House of Worth was by no means the only fashion palace in Paris, there were over twenty couturiers who vied for attention along the Rue de la Paix and on Place Vendôme. Amongst these were Paul Poiret, Jeanne Margaine-Laxroix, Jeanne Paquine, Jeanne-Marie Lanvin and Coco Chanel, who opened her first shop in 1910. One demimonde attending Longchamp was none other than Mademoiselle Gabrielle Chanel, pre-boutique days and mistress at the time to a wealthy heir of a textiles empire, Étienne Balsan. Coco showed up to Longchamp in a then-revolutionary ensemble: an unadorned simple, loose-fitting frock, a style that would propel fashion onto a brand new trajectory in the Roaring Twenties. No structured corsets, garters, whalebones, chemise, gussets, false hair, brassieres or trailing silk skirts for Ms Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel. Instead, the feisty flapper dress was born following Coco’s revolutionary and rather racy Longchamp forays. But she wasn’t alone in her forward-thinking fashion …

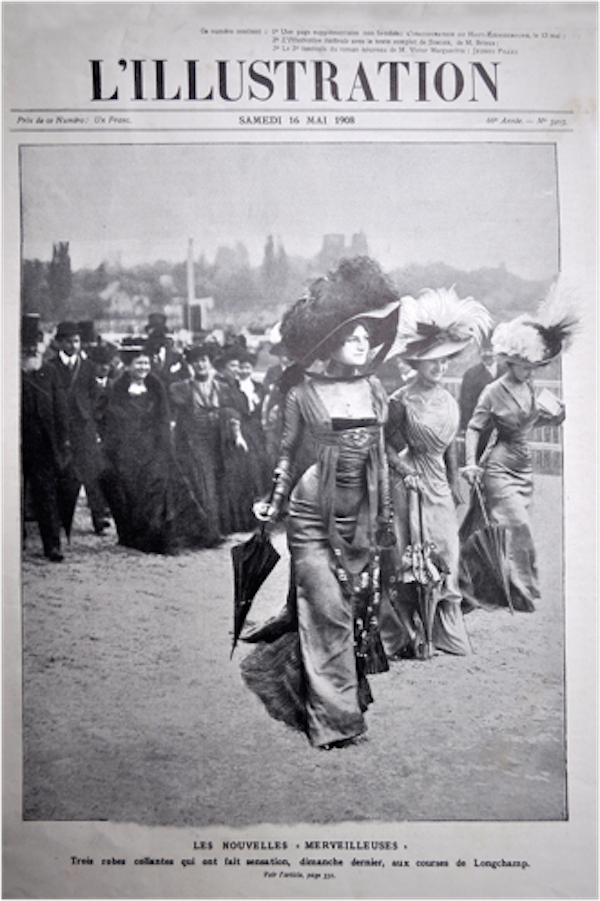

In the Spring of 1908 yet another Paris-based designer sent three ravishing models in what was to become the famous new 20th century silhouette, to the racecourse at Longchamp. The effect was dramatic: spectators and the press called these women ‘a monstrosity’, claimed they were ‘semi-naked’ and showing vulgar décolletage. The young designer was Jeanne Margaine-Lacroix who had, like Coco Chanel, unconventional designs on women’s fashions of the time. Out with the bell-shaped, pouffy crinoline skirts and expansive dresses; she famously used stretchy silk jersey to create hip-hugging, figure skimming body-con dresses that would accentuate every curve on the female body. With skirts scandalously split to the knee, French weekly paper L’Illustration, reported on appalled women marching their menfolk out of Longchamp en masse.

L’Illustration’s front page featured these ‘outrageous’ women, calling them Les Nouvelles Merveilleuses, in reference to a historic period at the end of the French Revolution when aristocrats who survived the reign of terror staged their own fashion revolution. Soon enough every young woman in Paris wanted to burn her Victorian outfits with their corseted waistlines and exaggerated chests and instead, sport slender and slinky dresses like the ones worn by Jeanne Margaine-Lacroix’s three Longchamp vixens. The desire for a new silhouette was unstoppable and Jeanne Margaine-Lacroix’s new silhouette had properly ‘sounded the death-knell’ for the previously worn constrictive ensembles.

“At Longchamp, one could introduce a new fashion to great public acclaim,” says Potvin, “yet a wearer also risked ridicule should a gown be poorly received, while a designer chanced a devastating blow to his newest design and potential financial disaster in the case of a fashion flop”.

La Belle Époque closed with WW1, the days of plenty and prosperity were over. Fabric availability, choices, shades and styles, for obvious reasons, became simpler and more practical as a new age dawned in the 1920s. Longchamp had witnessed all these foibles and whims and set the standard (and the catwalk) for a cut-throat industry.