Europe is filled with scores of enchanting abandoned and underused historic structures that have survived war and ageing. Only now, they’re offering shelter to those in immediate need: refugees. Cathedrals and churches, halls and barns have successfully sheltered armies, citizens and the sick in the past, surely the forgotten old wings of once-great castles and country houses could do the same? Just as neighbourly kindness and compassion are extended to those in dire need, physical structures, too, can play their part in times of crisis, filling the gap in our basic human need for a roof over our heads.

Ukrainian cities – like those in many in other war-torn regions – have been levelled, with homes, schools, apartment blocks, business districts and hospitals reduced to charred dust, often leaving families with no choice but to flee the apocalyptic devastation and look for refuge elsewhere.

Now, it’s true that old country piles may not be the warmest and driest of residences and perhaps the room layouts are a bit odd, but they’re a safe and secure refuge. A roof is a roof after all! The adaption of buildings for new uses is nothing new, the famous Pantheon in Rome was a public bath, then converted to a temple and finally refurbished as a church. Like all good plans, the devil is in the detail – the supposed obvious and simple solutions (even with the best will in the world) are never quite so easily executed, and success is never guaranteed. As any architect worth their salt will tell you, the need for shelter is so much more than just the availability of bricks and mortar; a home is created out of being able to make a personal choice of location and layout, and eventual personalisation. In the case of refugees and people fleeing persecution, we’re talking crisis intervention and often a case of ‘needs must’. Marrying traumatised individuals with a beautiful castle in the woods may seem a positive solution, and in many cases it does indeed fill the immediate, short-term need for shelter and safety and does offer a short respite to catch one’s breath and ‘regroup’. Technicalities such as ownership, approved uses and local prejudices however, also get in the way and there’s often a niggling undercurrent of applied rules, regulations and other details that temper the ability to reoccupy these relics from the past.

Let’s explore a few inspiring examples of unlikely refugee abodes …

Guédelon Castle and Château de Saint-Fargeau, France

Guédelon Castle looks like a medieval chateau under repair, but it’s actually not even yet complete. Guédelon is an experimental project that’s taken over 25 years to build using entirely historic construction methods to create an authentic contemporary castle, vaults, towers, halls moat and all. After some 10 years, a couple of towers, the great hall and some enclosing walls have been completed. And for one Ukrainian family of refugees fleeing the destruction of Kyiv, it was a delight to be invited to stay and participate in the project before finding a longer-term home in Auxerre — a small town about 30 miles away.

Owned by the founders of Guédelon Castle is Château de Saint-Fargeau, a truly massive 15th century towered and moated castle-palace. Isolated in a grand forested estate and offering aristocratic adventure pastimes, boating, horse riding and hunting, it too has offered shelter to Ukrainian refugees as a temporary haven for those awaiting visas to other countries. “The generosity was almost overwhelming,” said one of the Ukrainians who were welcomed to the chateaux with a fully stocked fridge and a cheerful itinerary of activities for the children. “It really does put your faith back into humanity,” he said. A total of 30 people have stayed at the two castles since the outbreak of Putin’s war in Ukraine.

Pessat-Villeneuve, Puy-de-Dôme, France

Close to the Puy-de-Dôme, the youngest of a chain of dormant volcanic mountains in the lush Massif Central range in the heart of France, lies the peaceful village of Pessat-Villeneuve. A settlement of 600 inhabitants have adopted a thoughtful and structured approach to helping refugees. There’s an old castle in the village, which also functions as the public hall. The mayor initiated a universal refugee programme offering temporary shelter in the castle lodgings – to those from the Middle East, Africa and beyond. Refugees are given board for no more than 4 months until longer-term housing is secured by the mayor’s office in the region. The castle will never be home, never be advertised as home, but acts as an orientation centre, familiarising incomers with language and local customs, from bike riding to shopping.

The Czech Castle of Bečov nad Teplou (dating from the 14th century)

Sixty Ukrainian refugees arrived at the Castle of Bečov nad Teplou in The Czech Republic, a 13th century rambling hilltop fairytale fortress, crowned with colourful domes and towers standing above a tiny village of 1000 inhabitants. Albeit very grateful for the immediate shelter, safety and security, most refugees still yearn to return to their own modest homes in Ukraine.

The Roman and Byzantine Temples at Baqirha

Like the houses of the gods, the Roman and Byzantine hilltop ruins at Baqirha close to the Turkish border offer a very traditional refuge spot for many Syrians fleeing conflict in the south of the country. This is a centuries-old lofty and isolated pilgrimage destination, well away from trouble in the plains below. The slopes are littered with the remains of massive walls and colonnades of the white marble temples.

The remains of the shattered enclosures provide shelter from the wind and define the residential living pattern. One resident reports, “I chose this place because it provides peace of mind, far from overcrowded places and those riddled with disease”. Recycled plastic awnings and reused metal sheeting lean incongruously against the ancient walls, solar panels complete the dystopian picture. Albeit without water and drains, this is a home of choice, a spiritual haven, albeit before the conservationists move them on.

Cinecittà Film Studios, Rome

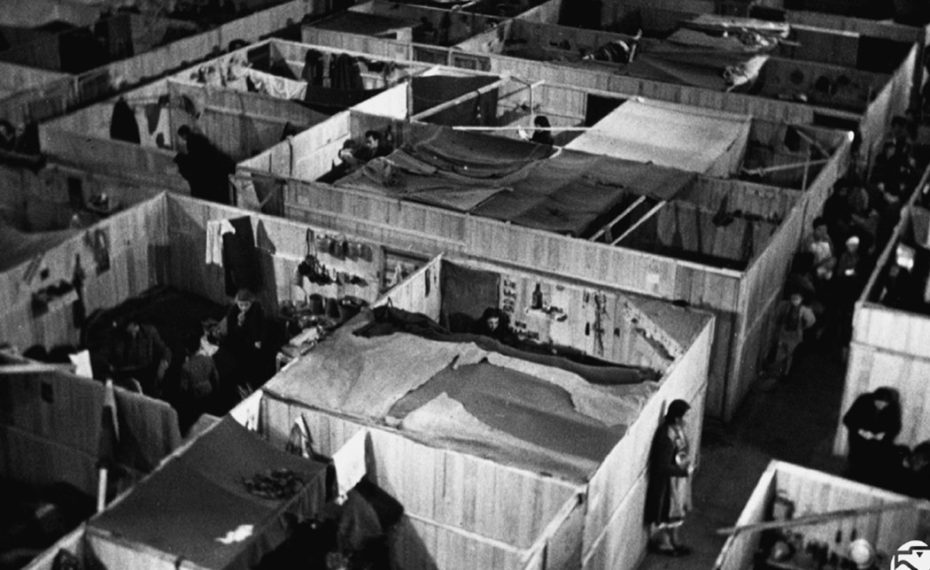

The Cinecittà film studio (Italy’ Hollywood) was partly destroyed by the Allied bombing of 1943/4. Between 1945 and 1947 the studios became home to 3,000 displaced Italian and international refugees, camping on the massive sound stages. Perhaps not home, but there was work, some even ending up doubling as extras as the studio attempted to resume production!

It’s clear the old houses and castles can provide shelter and safety, just as they were originally intended to do. The human factor, however, is known to put a spanner in the works – humans are immensely complex and fragile, especially those who have experienced trauma. Added to that cocktail are the local hosts and the obligatory municipal red tape, often frustrating the process. Relics can physically be adapted and repaired to serve a very commendable and noble purpose, but they inevitably come with their own political, practical and demographic baggage, somewhat thwarting their long-term ‘success’ as residences for refugees.