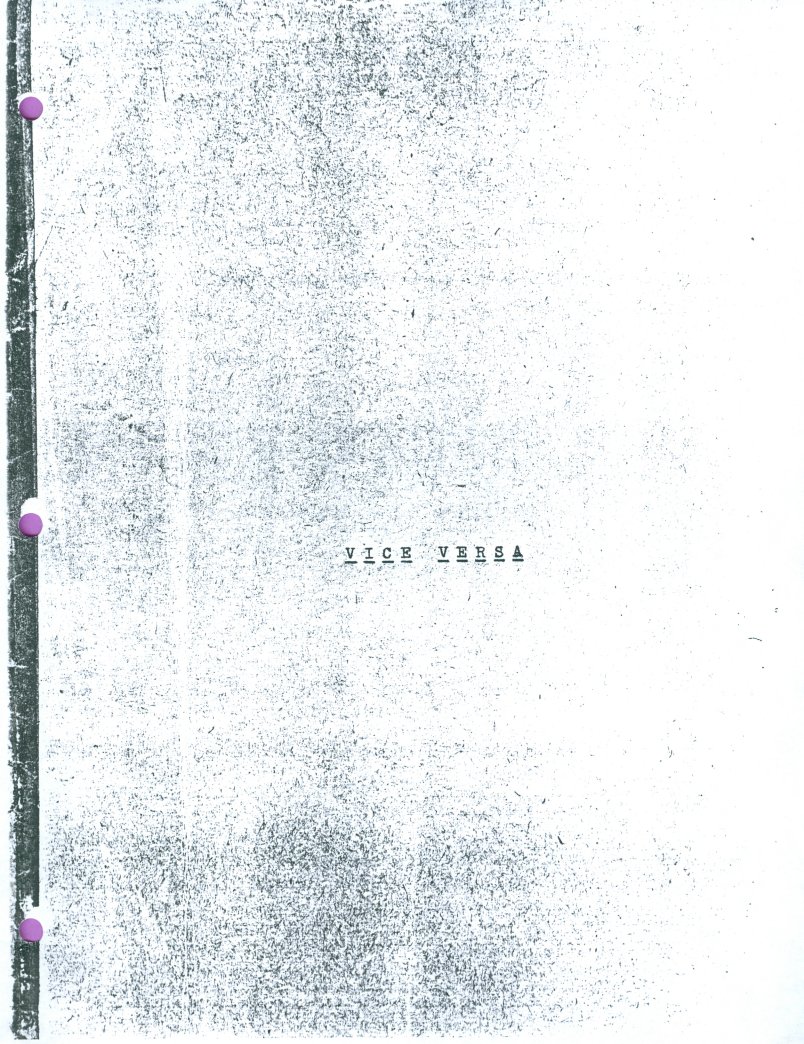

Hollywood has a thing for origin stories at the moment, and one origin story in particular begins in Los Angeles, in an unassuming building on Gower Street, just off Melrose Avenue. This is not the origin story of a Marvel Comics character, or even of a Hollywood bigwig getting their own biopic. Now part of the broader Paramount Pictures studio lot, in 1947 this nondescript building in magnolia housed the Publicity Department at RKO Studios. Today it’s known as the Lasky Building, after Jesse Lasky, pioneer of the motion picture and key founder of what would become Paramount Pictures. This is not Lasky’s story either. Instead, this is the story of a secretary who went by the name Lisa Ben. Or, at least this is what she went by in certain, knowing, circles – but more on that later. Having been told by her boss that it was vital she look busy at all times, Lisa Ben got busy, alright; busy using the office’s Old Royal manual typewriter, white bond, and carbon paper to make what would become the first lesbian publication in the United States, Vice Versa.

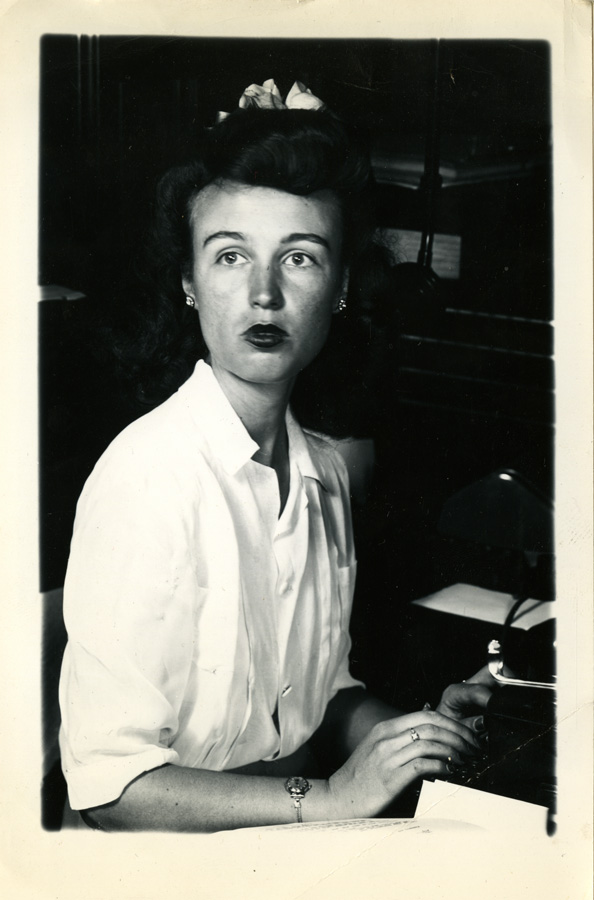

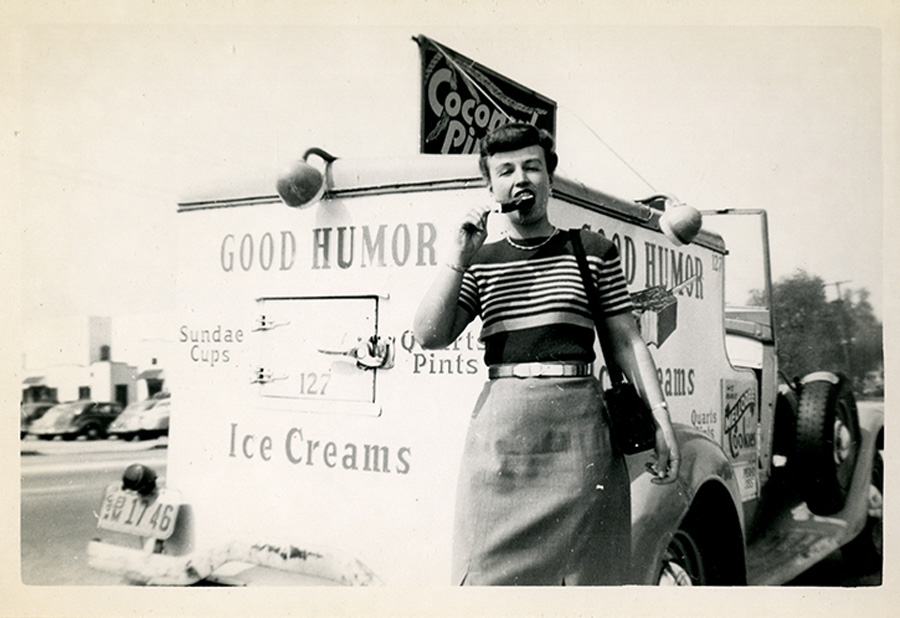

Behind the pen name Lisa Ben, writing away at her desk on RKO’s dime, was Edythe Eyde. Born in Fremont Township, California, in 1921, she grew up on an apricot farm in Los Altos whilst her father served in civilian defence along the Pacific Coast following Pearl Harbour in 1941. During the war she worked as a secretary for the War Dog Reception and Training Center in San Carlos, from where she would often write to her brothers fighting in Europe using the center’s typewriter. These letters would later become part of the Washing Post’s “Letters from War” project. In 1945, she moved to Los Angeles and by 1947 was working for RKO, where she would go on to continue misusing office equipment – all the better for us.

Vice Versa was a small, personal project – the grassroots of grassroots – in that Eyde was physically limited by the amount of copies she could produce by herself – like the familiar tale of the self-publisher today, she was writer, editor and publicist all in one, using carbon paper to make duplicates, no more than 10 – but also in that the drive behind making it was a very simple, very human one. “I knew the way I felt, but I didn’t know how to go about finding someone else that was that way and there was just no way to find out in those days. You know, everything was pretty closed about things like that. I wrote Vice Versa mainly to keep myself company because I thought that although I don’t know any gay gals now, by the time I finish a couple of these magazines I’m sure I will. I was such a little optimist,” she told the journalist Eric Marcus for an oral history book that later became the podcast, “Making Gay History.”

Being a one-woman show, Eyde had to wear many hats to produe Vice Versa, but she wasn’t entirely new to the zine culture. Years earlier, whilst a student at the exclusive Mills College; a women’s school in Oakland, to “study business and prepare for matrimony”, she sent a letter to science fiction writer and publisher Forrest J. Ackerman, creator of the zine Voice of the Imagi-Nation, otherwise known as VOM. In the letter she expressed her disappointment that her college did not offer Demonology as a course, an area, along with witchcraft and the occult, that Eyde had been inclined towards since a young child. “… and if I were to suggest such a thing,” she wrote, “I am afraid that the authorities would have me in a straight-jacket quicker than you could say ‘Cagliostro.’”

Ackerman was impressed, and invited her to be a contributor to VOM. With a knack for illustration, she created many cartoons and even designed some of the zine’s covers. In one issue she confessed to being a Satanist, drawing quite the response from the largely male readership, with one writing in to say, “She says she is ‘interested in Devil worship and Black Magic purely for revenge, power, love of mystery and just pure devilishness’ but NO FURTHER THAN THAT. Well how much FURTHER THAN THAT can she go??”

A few years after they met, a besotted Ackerman proposed, but Eyde turned him down. Later, he would talk of how he should have clocked on sooner: “When we went to movies together, I would come out raving about Marlene Dietrich and she came out raving about … Marlene Dietrich, not Gary Cooper. Like me, she liked Betty Grable’s legs, not Clark Gable’s ears.”

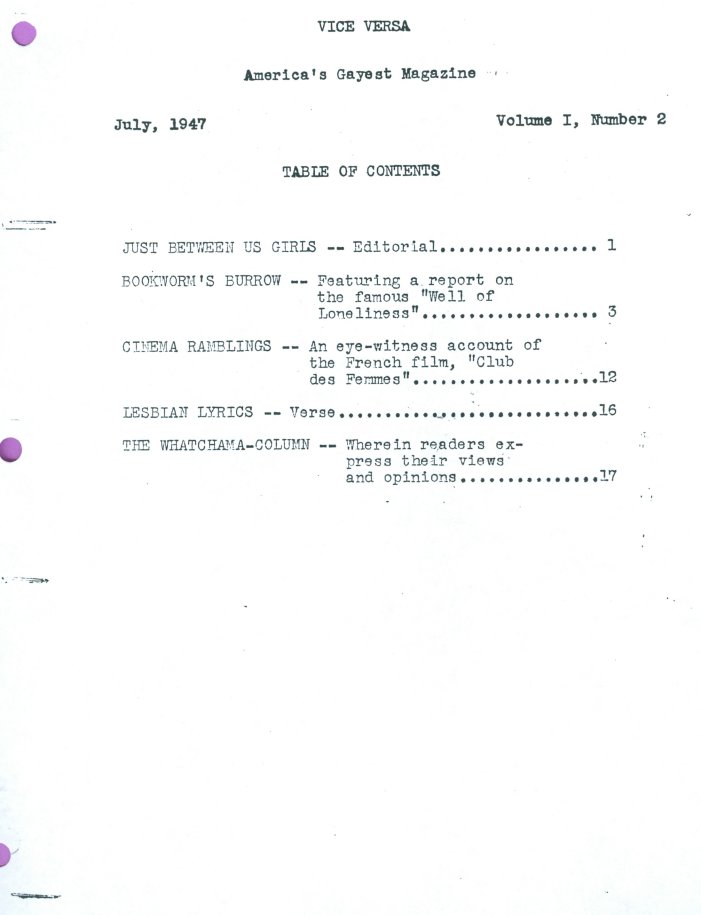

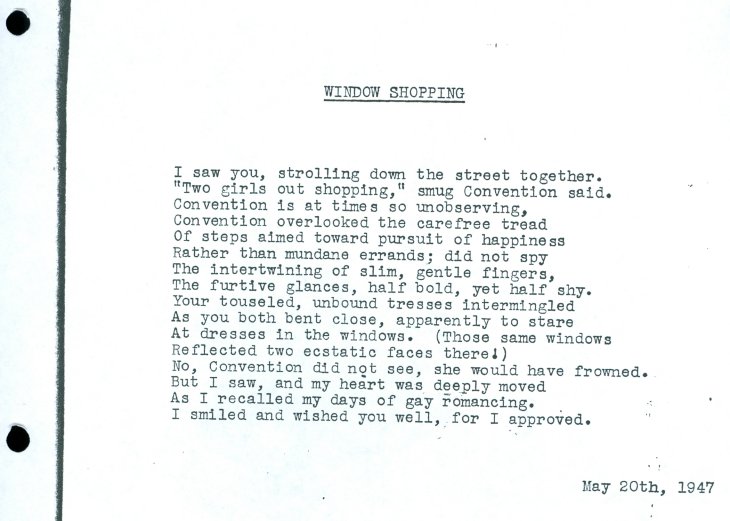

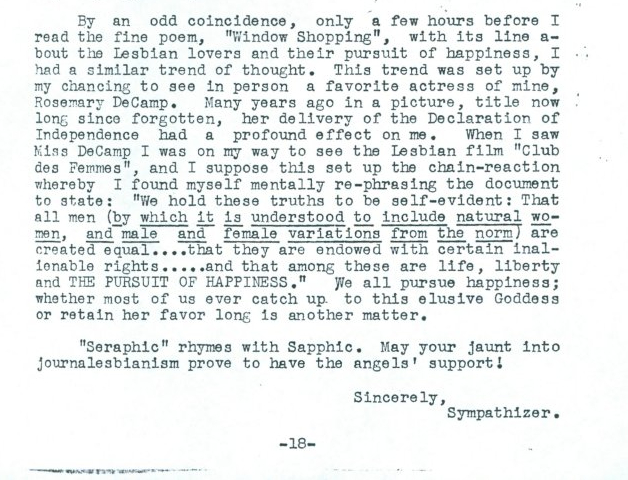

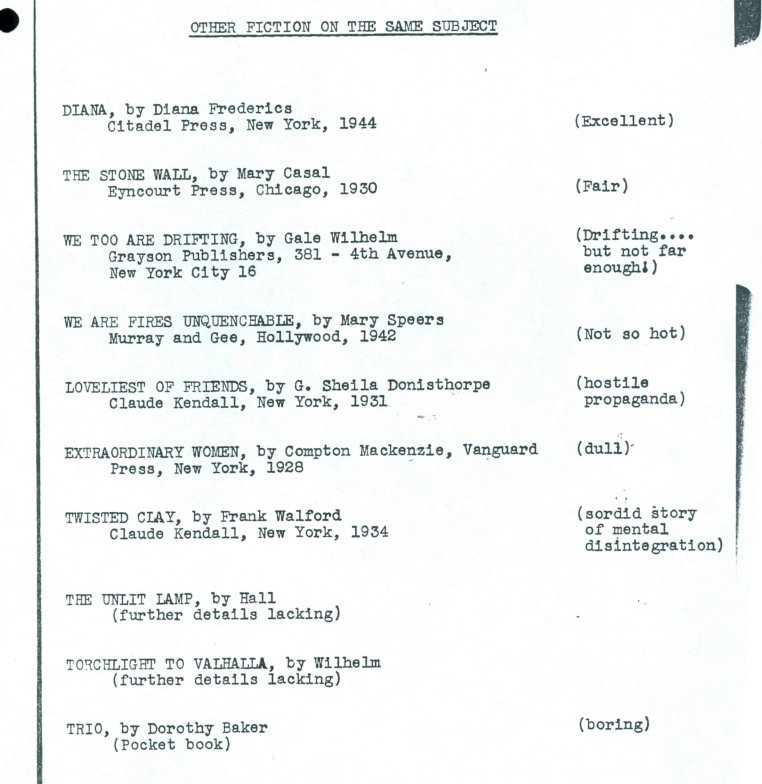

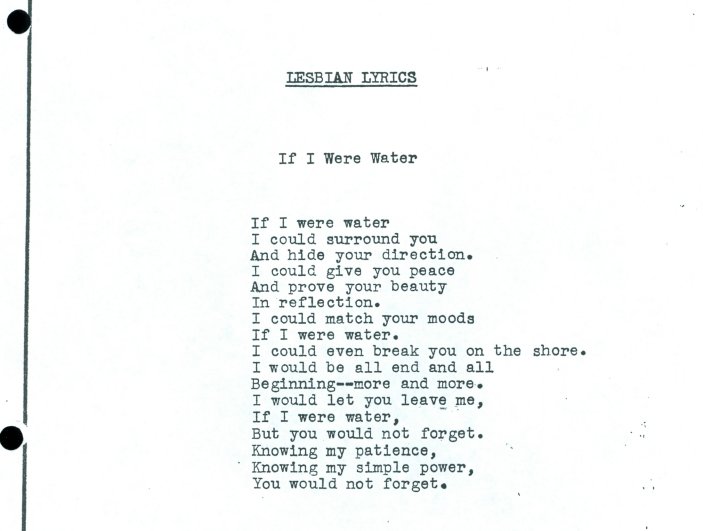

Compiled almost completely by Eyde, with some contributions by readers (though never enough), Vice Versa featured stories, book and film reviews, poems, letters to the editor, and the ‘Watchama-Column’ – a moving section of the magazine left over for what Eyde described as ‘fantasising over’ or ‘imagining’ the potential of the future for gay communities, whatever that may be.

One review was for the 1937 film Children of Loneliness, adapted from the novel Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall, a popular lesbian novel from 1928. In possibly one of the earliest cases of queer-baiting, Eyde laments the film’s lack of relation to the base novel, writing: “Those in the audience who hoped to view scenes of lesbian love were sorely disappointed. There was not the slightest demonstration of affection between two women displayed upon the screen, aside from a brief flash of one girl with her hand upon the shoulder of another, a casual gesture indeed.”

In the October 1947 edition, Halloween is, unsurprisingly, the theme. Eyde extorts the virtues of that time of year, a time of liminality and letting loose. All those outcast creatures that are feared, held in contempt, denied of existence, are now “free to roam the earth unrestrained, uninhibited.” An appropriate day, Eyde writes, “for those of us who must masquerade the other three hundred and sixty-four days of the year.”

These outcast creatures come in many forms, by day. They are salesladies, “selling nylons to madame.” They are secretaries in insurance firms, advertising agencies, and movie studios. They are nurses, waitresses, and street car conductorettes (that last one, admittedly, not so much today.) But come night, so Laurajean Ermayne – another pen name – writes, “I am butch; I am a white-starched shirt. Cuff links. A bow tie. I am close-cropped hair. I am a husky throat. I am manners. I dance, and I lead my partner.”

Vice Versa, and its recipients, were undeterred by the end-of-the-world feelings that abounded in the wake of the very real threat of the atomic bomb in the late forties. In a letter to the editor from issue two, a reader remarks, “Of course, the imminence of Armageddon suggests that we may all be atomized before the world wises up on the confusions that cloud the minds of men; that we will all become one–male, female, homo, lesbian, bi-sex–in the amalgomating atomic cloud when fission writes Finis to homo saps…”

The pages of Vice Versa are full of this optimistic looking towards the future – even with the threat of the A-bomb hanging over everyone. Whether from contributors or Eyde herself, there is a strong feeling that change is coming, slowly but surely, and all that is needed is just a little push for the proverbial dam to break. But perhaps not just yet. Let’s circle back to that nom de guerre of her’s – Lisa Ben. The puzzle savvy amongst you will have clocked onto it as a non-too-subtle anagram of lesbian (later, when writing for another lesbian publication, The Ladder, Eyde would suggest the use of another pen name, Ima Spinster).

But why the tricks? Why the secrecy? In short, there was a very real threat of arrest for anyone caught distributing queer materials. It was the early days for LGBTQ+ rights in the US in 1947, the year Vice Versa began circulating. A brief primer to bring you up to speed: In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association will list homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance. A year later, Eisenhower will sign an executive order banning homosexuals from working for the federal government, calling them a ‘security risk’. The first known lesbian rights organisation in the country, Daughters of Bilitis, will not be formed until 1955. Stonewall is still to come, in 1969.

This necessary secrecy affected distribution, too. Originally sending copies through the mail, Eyde stopped when she was informed of the dangers involved in getting caught by the Postal Service. Instead, she went really old-school and handed them out in person at places like lesbian bar the If Club, relying on word of mouth and a kind of sharing system, whereby when someone was finished with their copy they passed it onto another and so on, a chain-link of desperately needed LGBTQ+ material amongst the so-called Uranian Underground. In subsequent editions of the magazine, Eyde would continiously express her delight and surprise at the size of the audience Vice Versa was reaching, and their appetite for more. But this appetite largely failed to produce contributions to the magazine’s content, despite Eyde’s insistence that readers send in their offerings. A monthly output was too much for one women to deliver alone.

In the end, Vice Versa would run for only nine issues. Its final edition, in February of 1948, included no indication that it would be the last. Instead, it simply quietly vanished from circulation, becoming a kind of fond tale passed around by those in the know. Alongside the lack of contributors, around the time of its last issue, Eyde lost her job with RKO. Howard Hughes had just purchased the company, and subsequently laid off 75% of the workforce. She quickly took up a new position at Universal Pictures, but it left no time for making herself ‘look busy’ and as a consequence, no time for Vice Versa. And that, as they say, was that.

Or was it?

Not quite.

Vice Versa was over, but the following decade Eyde began writing for The Ladder, the first nationally-distributed lesbian magazine, run by the Daughters of Bilitis, of which she was was now a member. And writing wasn’t her only cause – Eyde was also a talented musician. Not in the classical sense like her parents would have liked, after eights years of violin lessons, but in a rather more spirited sense – writing and performing gay-themed parodies at a local gay club called The Flamingo. Popular tunes like “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter” would become “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write My Butch a Letter.” The Daughters of Bilitis billed her “the first gay folk singer.”

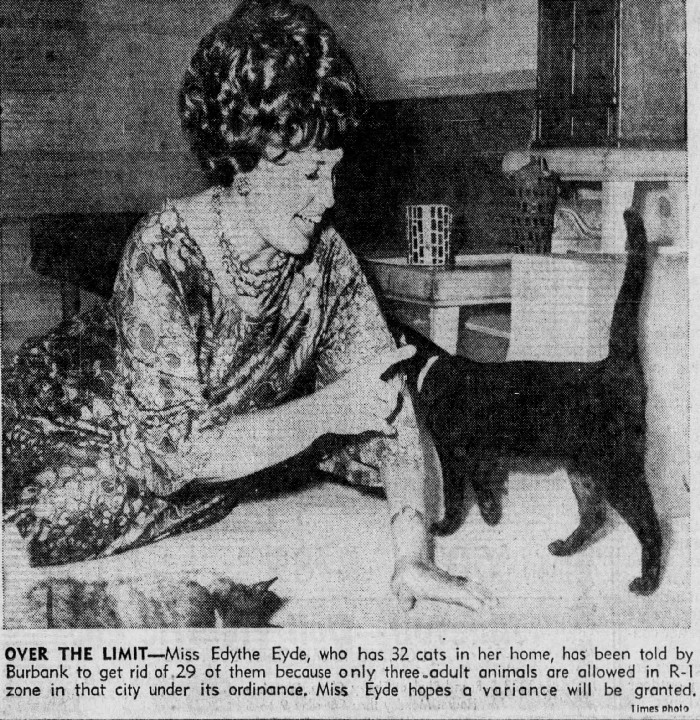

In 2010, The Association of LGBTQ Journalists (NLGJA) welcomed Edythe Eyde into its Hall of Fame, and in 2016 the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries announced that her papers, including a complete set of Vice Versa‘s nine issue run, were now housed with them and available for public research. Just a few months earlier, in December of the previous year, Eyde had passed away after several decades of living quietly in Burbank, California, a largely unknown pioneer of LGBTQ+ rights and proud cat lady (32, at one count).

Decades later, Eyde would be asked about the reasoning behind the name, Vice Versa. Straight from the Latin vice, “a change, alternation, alternate order” and versa, “to turn, turn about”, it doesn’t take too much reading between the lines. “I called it Vice Versa,” Eyde said, “because in those days our kind of life was considered a vice. It was the opposite of the lives that were being lived — supposedly — and understood and approved of by society. And vice versa means the opposite. I thought it was very apropos.”

In Unspeakable, his history of the gay and lesbian press in the United States, journalist and historian Rodger Streitmatter noted that Vice Versa “contained no bylines, no photographs, no advertisements, no masthead and neither the name or address of its editor… yet it set the agenda that has defined lesbian and gay journalism for 50 years.” A small but vital vehicle of communication for gay women, Vice Versa was a trailblazer as one of the first life-lines thrown to “the boy-girls, the gayborn. The children of the night, seeking the light, not as moths around the flame but as the flames! The fires unquenchable.”

All nine issues of “Vice Versa” can be seen reproduced in full on Queer Music Heritage’s website.