Celebrities from Judy Garland to Madonna to Lady Gaga have been granted the title “gay icon,” but there’s one often-forgotten figure who deserves a spot on this list: Bugs Bunny. The Warner Bros. Cartoon character not only experimented with gender presentation but also married a man in at least three cartoons, in the 1950s. With all this talk about what is and what isn’t appropriate for children to see, now is an opportune time for a brief compendium of Bugs Bunny in drag.

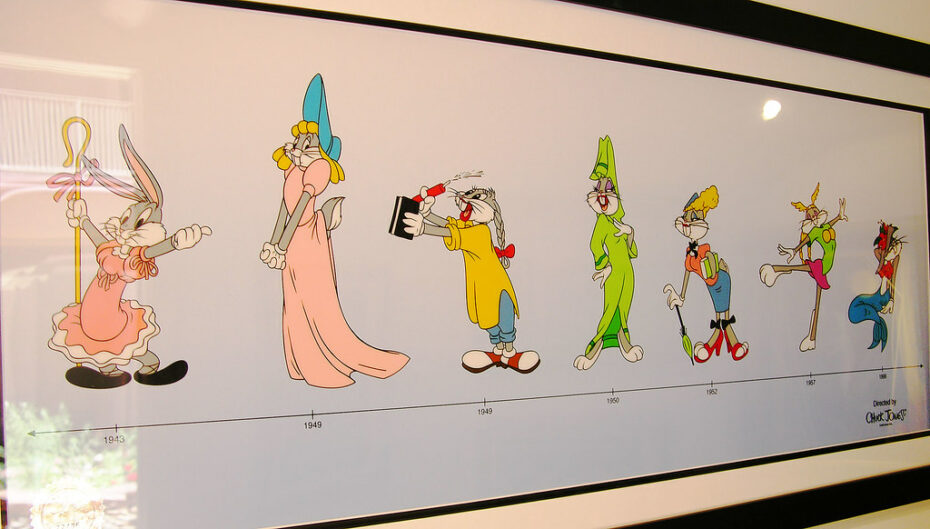

Chuck Jones, one of the creators of the “Wascally Wabbit” admitted in the ‘90s that he always imagined Bugs as a “transexual” (a word that we of course don’t use anymore, but was the language he had for trans folks back then). The character dates back to the 1930s, starring in Looney Tunes as a mischievous, wise-cracking rabbit with an innocuous Brooklyn accent. With his signature catchphrase “Eh…What’s up, doc?” he became the mascot for Warner Bros. during the golden age of animation. In fact, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, he’s the ninth most-portrayed film personality in the world.

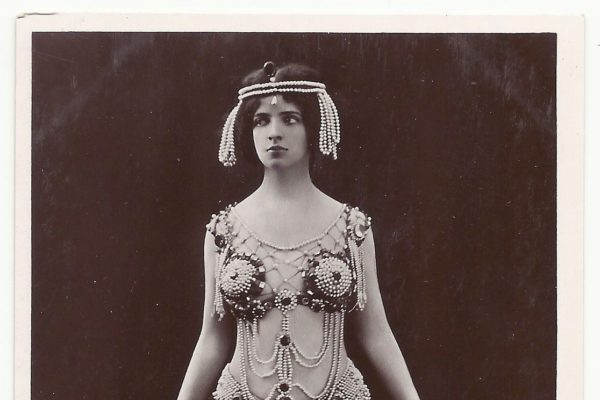

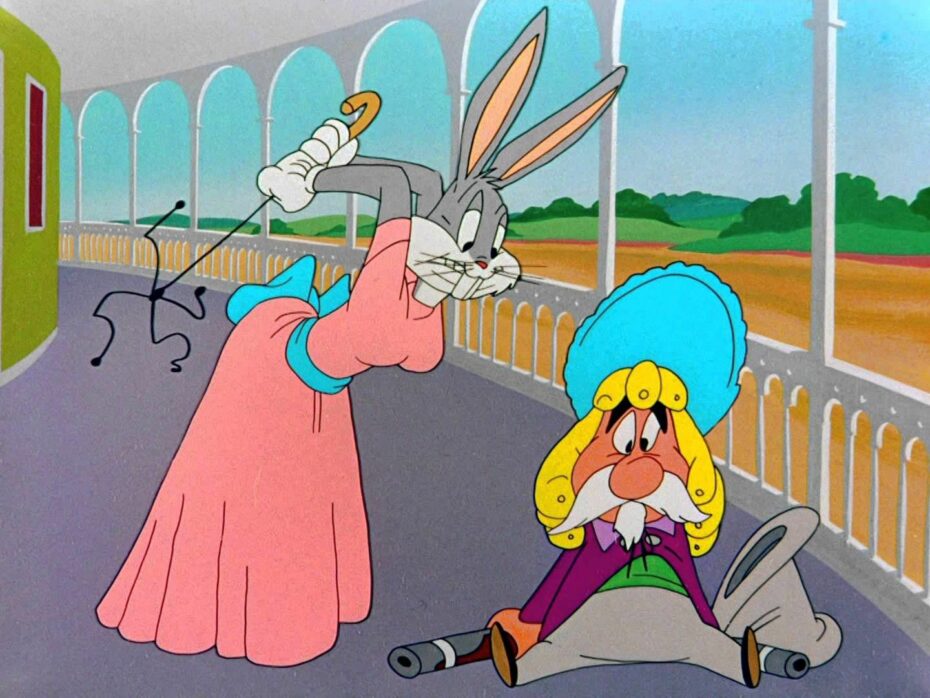

While wearing women’s clothing was often a way for Bugs to get out of a sticky situation, his unabashed gender-bending also became part of his personality. Most importantly, pretending to be a woman was never just the butt of a joke. Most often, the costumes were a tool in the constant game of cat and mouse (or rabbit) between Bugs and Elmer Fudd, the hunter always on his tail. Often the seductress in outfits worthy of a magazine pinup (and always with bright red lipstick), Bugs successfully charmed his archenemy and could live another day.

These characters — from a mermaid to a cancan dancer to a Viking — were not making fun of femininity, but in fact, showing how it could be a source of power to get what you wanted. Interestingly enough, Bugs became sexually liberated during an era when the 1930 Hays Code banned “sex perversion or any inference to it” and self-censorship abounded after the establishment of the Federal Communications Commission and the first set of commercial TV regulations. But while live action stuck to these “family-friendly” standards, animation became a field for increased experimentation.

As Melanie Kohnen, an associate professor of rhetoric and media studies, told Insider, “People actually found ways of inserting queerness into cartoons and stretched the boundaries of the Production Code because animation in itself is a medium that already lends itself to surrealness or strange situations.”

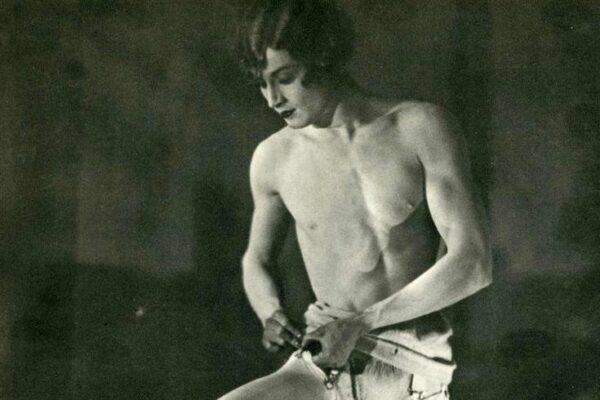

Crucially, Bugs was aware of the fact that as a woman, he would be underestimated, and no one would expect his conniving plans. He dressed as a bobby soxer (a 1940s enthusiastic teenager, often a fan of Frank Sinatra) to get back at opera singer Giovanni Jones (yes named after Chuck Jones), who had grown frustrated by Bugs interrupting his rehearsal. So when asking for his autograph, the “bobby soxer” puts a bomb in his hands. It is a cartoon, after all. And these queer acts have continued through Bugs’ decades-long spotlight in the media. Who could forget when he planted a big kiss on basketball star Michael Jordan in “Space Jam” to prove that he was “real” and not just a figment of Jordan’s imagination? And Bugs isn’t the only one: His co-star Daffy Duck also often wears women’s clothing, and given their close, though often contentious relationship, they’ve been described as “an old married couple.”

While back when he was being created, no one would have called Bugs gay, he often is a barely shielded example of queer coding. Even RuPaul said that Bugs Bunny was his first introduction to drag. Especially in an era with next to no queer role models, it’s clear why a young person would attach themselves to a figure whose gender fluidity goes behind strict binary confines or who is overtly depicted as part of a queer couple, even if it is with their worst enemy. (Although Out wrote in its list of “25 Cartoon Characters Who Should Just Come Out Already” that Bugs’ “long-standing rivalry would play out really well on a reality show if set in the current era.”)

Back in 1995, Eric Savoy argued in an article for The Ohio State University Press that it was due time to explore Bugs, and cartoons in general, through an academic lens: “I am particularly interested in recuperating Bugs Bunny as a queer cultural icon, a parodic diva, whose campy excess and canny games are profoundly though tacitly indebted to the African-American tradition of Signifyin(g), especially in the potential to short-circuit the self-congratulation of an impercipient adversary.”

The origin tale for this form of wordplay comes from the Signifying Monkey, who bested a lion through his words, often messing with the literal and figurative meanings. Bugs Bunny too used this verbal trick to overcome his oppressors.

For example, when he appears to shoot Elmer Fudd while dressed as a ‘50s bombshell and laments, “Oh, how simply dreadful. Your poor little man? Did I hurt you with my naughty gun?” And he also subvertly questioned gender norms. As Savoy writes, “Bugs Bunny parodies ‘woman’ in order to insert himself into Elmer Fudd’s heterosexual fantasies and heterosexist compulsions; to sabotage this script he offers duplicitous signs of femininity, signs which are patently transparent and constructed to us, but entirely opaque to Elmer’s gendered (il)logic.”

Of course, it would be wrong not to mention the ways in which Bugs’ explorations of different identities dipped into the realm of racist appropriation and making fun of other cultures, notably the presence of Black and yellow face in older cartoons. While these depictions have luckily become less common in a time of greater representation and cultural sensitivity, depictions of gender and sexuality are often still sticky. Look no further than the debate over the “de-sexified” Lola Bunny in the 2021 film “Space Jam 2: A New Legacy.” But during an era when politicians are gaining points by scaring parents into believing the media is influencing their children to pursue “divergent lifestyles,” there’s something liberatory, and clearly political, in holding a beloved character up as a queer icon. As Charles M. Young wrote in the storied Village Voice newspaper in 1975, in an article aptly titled “Oryctolagus Cuniculus — a.k.a. Bugs Bunny,” “beneath all that role playings, [Bugs Bunny] had focus,” for “after pulling a fast one on Elmer, Bugs always had the presence of mind to put on a tutu and pirouette into the forest, or play his carrot like a fife.”