Alma Mahler was no ordinary woman: She shared her first kiss with Gustav Klimt, kept diaries that offered an insight on fin de siècle Vienna the same way Anaïs Nin’s journals did for 1930s Paris with the same (if not more extreme) fabrication, and drove her ex-lover to such madness he commissioned a sex doll in her likeness once she ended their affair. But behind the legacy, Alma is the ultimate cultivator of a mythological icon and a curator of lies, puzzling musicologists with the “Alma Problem” as the unreliable narrator to her famous composer husband, Gustav Mahler’s life.

More than just a muse to her coterie of men, Alma composed and wrote. From her early years, the arts intertwined themselves like creeping tendrils in Alma’s life, since her father, Emil Jakob Schindler, became one of the most esteemed landscape artists in the Habsburg Empire. Alma spent hours by her father’s side in his studio, while her mother carried on with Schindler’s artistic colleagues and students. Once Emil Jakob Schindler died, Alma’s mother married Carl Moll, one of the founding members of the Vienna Secession ushering in the teenage Alma into the world of the Viennese avant-garde just as she hit puberty.

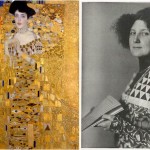

The teenage beauty left an impression on the art nouveau artists frequenting the family home, most infamously Gustav Klimt. Seventeen-year-old Alma fell for the artist, despite Klimt’s womanising reputation, but the artist also developed an obsession for the young girl, going as far as to follow the Molls to Italy. Klimt and Alma’s flirtation grew more intense: they met in secret and Klimt stole Alma’s first kiss. Things were cut short when her step-father discovered the scandalous relationship, irreparably damaging his friendship with Klimt, and fizzling Klimt and Alma into nothing more than a summer romance.

Alma soon discovered the power of her beauty, coupled with Nietzschian ethics, “Whoever falls, should also be given a push!”, she left a trail of broken artists behind (along with anti-semitic ideas, even though two of her husbands and some of her lovers were Jews). After Klimt, she discovered her love for music, but blurred the lines of her passions when she embarked on a stormy affair with composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, her music teacher. However, it was her future husband, Mahler, she met a year later, for whom she would mostly be remembered.

For Mahler it was love at first site, and only weeks later he proposed to Alma. Her family objected to his being 19 years older and his Jewish origins – but an even bigger stumbling block – Mahler wanted Alma to stop composing.

“How do you imagine both wife and husband as composers?” he wrote in a letter to her, “Do you have any idea how ridiculous and subsequently how much such an idiosyncratic rivalry must end up dragging us both down?”

“He thinks nothing of my art – and thinks a great deal of his own – and I think nothing of his art and a great deal of my own. That’s how it is!” Alma journaled, “Now he constantly talks of preserving his art. I can’t do that.”

Despite the creative differences, the couple got engaged days later, and married in the Spring. The moment Mahler married Alma, the lies began.

It was not only their age differences that made them an odd couple, but while Gustav was more introverted, his young wife was vivacious, beautiful and a socialite. She outlived her husband by 50 years, becoming the principle authority on the composer’s life. Scholars took the account of her husband’s life and work as a piece of music history, until the cracks began to appear and it seems that Alma Mahler left flawed accounts riddled with deliberate unreliable narration that painted Mahler and herself in a false, manipulated light. For decades, the foundation of any critical literature on Mahler using Alma’s misleading accounts earned itself the title, “The Alma Problem”.

Alma fabricated Mahler’s history by joining separate letters her husband once wrote together, sometimes altering letters before being published, determined to present herself in the centre and in the most positive light, as the selfless, powerless victim to her husband’s cruelty. She deleted references of her husband’s

kind gestures, eliminating any evidence that he brought her gifts. She also erased people she didn’t like from his correspondence. “It is now plain that Alma did not just make chance mistakes and ‘see things through her own eyes’. She also doctored the record,” said Jonathan Carr, who wrote a biography about Mahler in the 1900s.

Alma didn’t only spin a web of lies surrounding her husband’s relationship, but began an affair with the architect Walter Gropius, a young architect who’d become a key figure in the Bauhaus movement. Gropius let it slip to Mahler by “mistakenly” addressing a love letter to Alma’s husband. Even after the discovery, the two continued their affair in secret, until Mahler and Alma’s relationship improved thanks to a short analysis session Mahler had with Sigmund Freud, who, in classic Freud style, said the two were drawn into the relationship because they reminded each other of their respective parents. Gropius married Alma a while after Mahler died, but only after she ended her tumultuous relationship with Oskar Kokoschka.

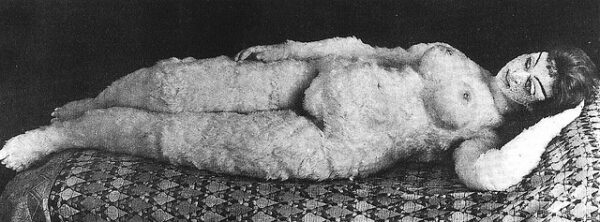

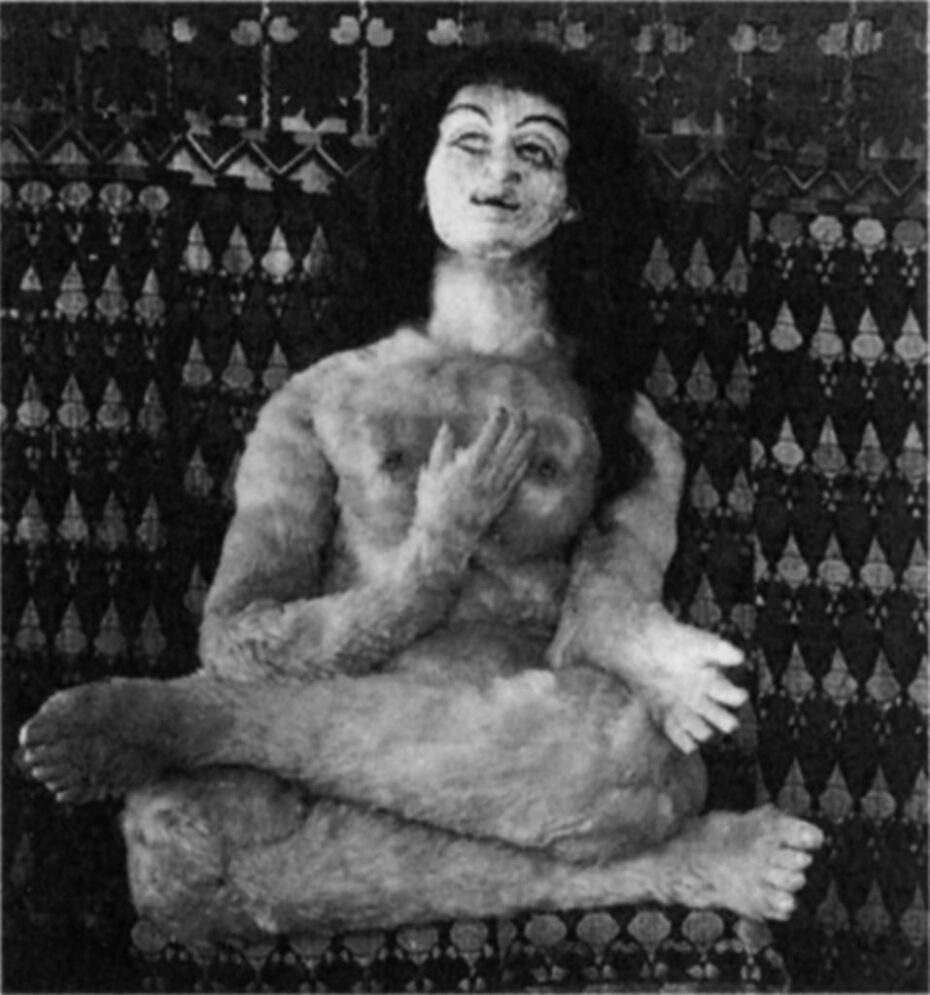

Alma had met the enfant terrible of the Vienna art scene in 1912. Kokoschka’s reputation was violent, unbridled; a beast. It was probably these qualities that drew Vienna’s most eligible widow. Kokoschka grew more obsessed by the day, painting Alma when he was not in bed with her. The relationship spiralled into toxic territory, fuelled by Kokoschka’s jealous outburst. But things got especially dark when Alma aborted her child by him (allegedly, he even stole the blood soaked cloth from the hospital) – and even more so when news of Alma’s marriage to Walter Gropius went public. In the style of the tormented, disturbed artist, Kokoschka commissioned a life size doll from Munich, stipulating it should resemble her in every detail.

Whether or not he wanted a sex doll or it was a coping mechanism for his rejected love, the doll was an epic fail. It looked more like a plush toy made out of fabric and wood-wool, fluffy and grotesque – which by the way, shouldn’t come as any surprise when you commission a sex doll of your ex.

Kokoschka used the doll more to take out his frustrations through art, painting and drawing it over and over again until he decided to throw a decadent party where the doll was a guest of honour. Champagne flowed liberally before Kokoschka beheaded it and broke a bottle of red wine over the head. Finally, the artist found a way to get over his break up after destroying her effigy.

Alma is a strange historical figure, but it can be easy to either reduce her to the men in her life or praise her as an independent woman who made waves in her community with her salons. Her compositions have slowly started to be performed again and recognised as an artist in her own right. However, sometimes it’s easy to idolise her on the flipside, but her cruel streaks, anti-semitic views and her outright lies reveal a dark side to this character. One thing Alma succeeded is curating her own life. It’s going to be hard to tell what’s real and what’s not, so best take her as a clever piece of living fiction.

Further reading: Passionate Spirit, The Life of Alma Mahler, by Cate Haste, Bloomsbury, RRP£26, 469 pages