In many ways, the history of the Louvre is the history of France, from the era of monarchs and the temples they built to their power to the radical ambitions of the French Revolution and Paris Commune. While many of the millions of tourists now flocking back to Paris will gawk at the architecture of the Louvre and its rich cultural offerings, an eye should also be turned to the history of this area of the French capital and the Tuileries, Paris’s missing palace; the disappearance of which marked the birth of the modern Louvre.

While it’s now the centre of Paris in the 1st arrondissement, the prime location that would hold the Tuileries Palace was once just outside the city boundaries, in an area that was often flooded by the Seine and was home to artisans who made “tuiles” (roof tiles). But its proximity to the Louvre Palace (begun by King Philip II in the 12th century to protect the city) led some royalty to start land development. After the death of her husband Henry II, Catherine de’ Medici moved into the Louvre but wanted her own residence. So she started construction on the Tuileries Palace in 1564 directly opposite, closing off the western end of the Louvre courtyard. Louis XIV lavishly grew and redecorated the Tuileries palace and his gardener, André Le Nôtre, also redesigned the Tuileries Garden. Celebrating the birth of the Dauphin with a spectacular Carrousel featuring equestrian feats and giving a name to the courtyard that is still is used today.

By 1750, Louis XV had already created a small private museum for the elite to display the royal collection in the Louvre – the early beginnings of the iconic museum we know today – and while the Royal Court was briefly housed in the Tuileries Palace, it eventually settled in Versailles and the Tuileries palace was gradually all but abandoned, used mainly for theatre productions. The gardens were soon taken over by Parisians, and in fact, the first manned hydrogen balloon flight took place on the grounds in 1783, with Benjamin Franklin, then ambassador to France, in the audience. It was only a few years later, in 1789, that Louis XVI and his family were expelled from their Versailles residence and taken to the Tuileries, where despite being prisoners, they lived in relative calm in the hall of the Manège, even being allowed to walk in the gardens (the steps to this part of the palace are still visible today) before the Reign of Terror and their grisly executions.

During this period, the museum in the Louvre also became open to the general public for the first time. The National Constituent Assembly declared in May 1791 that the Louvre would be “a place for bringing together monuments of all the sciences and arts.” Given the amount of looting that had taken place in the revolution, France’s National Assembly also sensed the urgency of an institution to “preserve the national memory.” As it was first known, the Musée central des Arts de la République opened on August 10 1793 with 537 paintings and 184 objects of art, three-quarters coming from the royal collection.

In post-revolutionary France, the soon-to-be emperor Napoleon Bonaparte took up residence in the Tuileries Palace, redecorating it in the Neoclassical Empire style to match his imperial ambitions. He targeted some of the buildings that had been destroyed during the revolution and built an arch in the Carousel courtyard in the style of Rome’s ancient Arch of Septimius Severus.

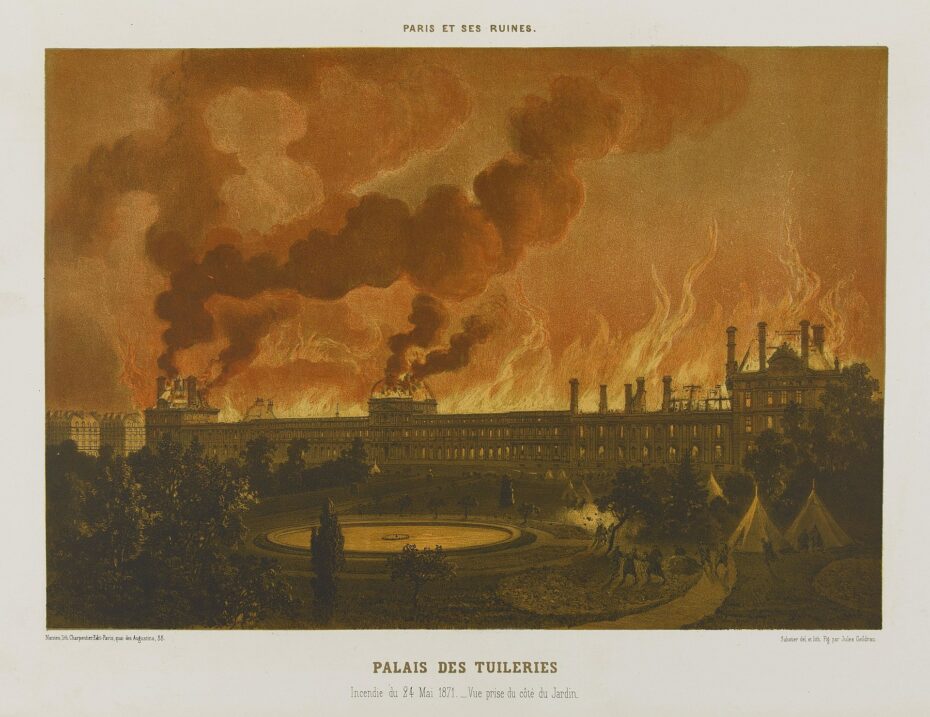

The palace went through another series of owners during Napolean’s exile, the Bourbon Restoration and the 1830 July Revolution, but it was during the 1871 Paris Commune, in the last days of the leftist uprising, that the palace’s history came to an end. On the evening of May 23, the building was set on fire, lasting for two days and gutting the palace.

As Jules Bergeret, the former chief military commander of the Commune, wrote in a note to the Committee of Public Safety: “The last vestiges of Royalty have just disappeared. I wish that the same may befall all the public buildings of Paris.” The emperor’s Louvre Library and some of the adjoining halls in what is now the Richelieu Wing were separately destroyed. But thanks to the efforts of Paris firemen and museum employees, the museum was saved.

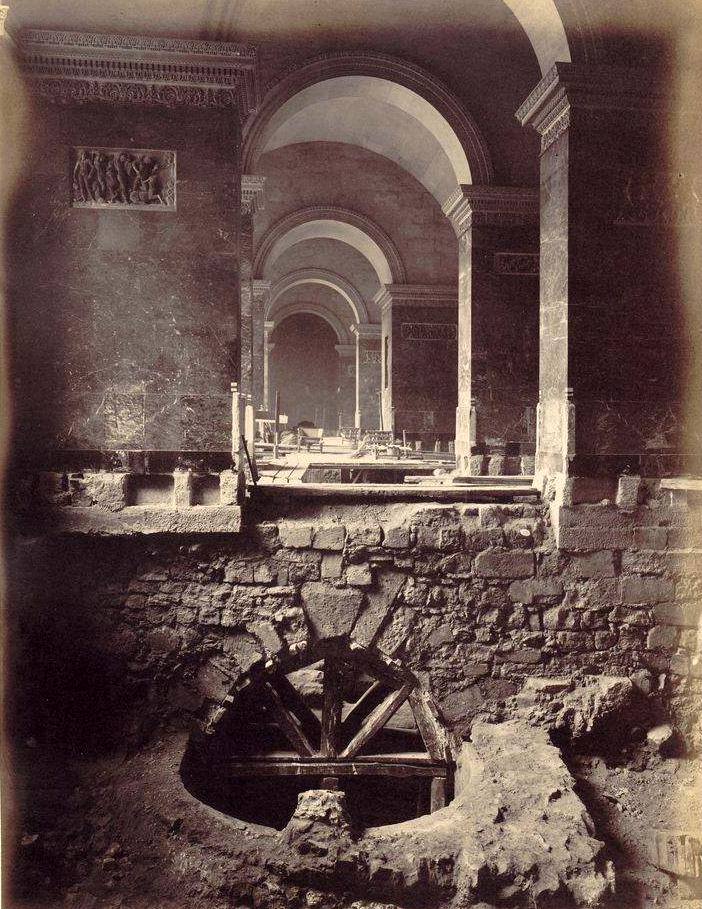

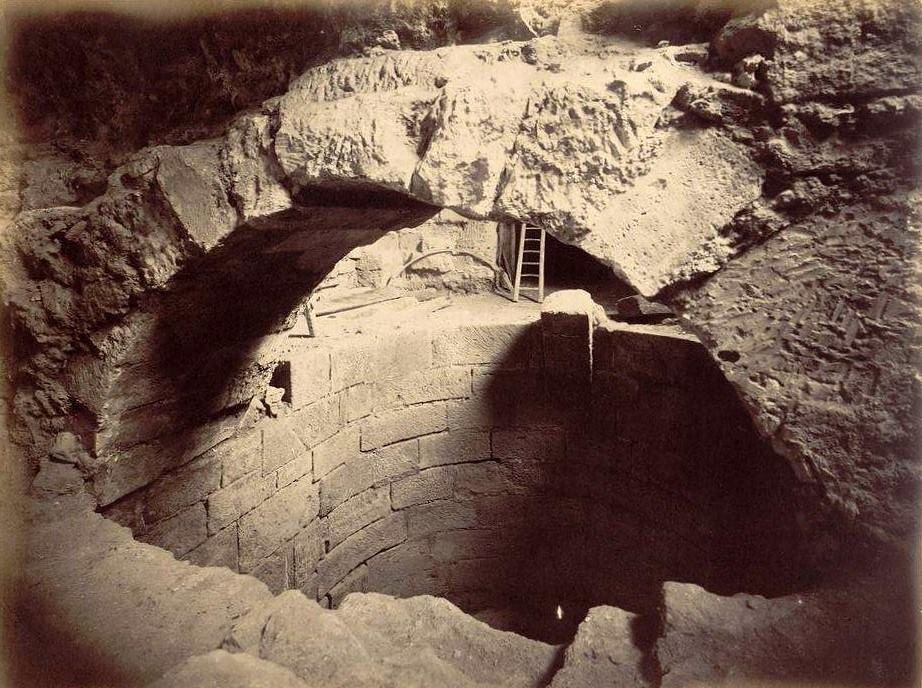

After a long debate, the remains of the Tuileries Palace were destroyed between 1882-1883. But the end of a relic to France’s monarchial past also marked a new era for the museum, allowing the palace to be entirely devoted to art, a softer display of France’s power. This modern “new” Louvre expanded, taking over the Flore and Marsan pavilions, which had been restored in 1874, and the north wing was doubled in width, stretching down the Rue de Rivoli. New rooms focusing on the antiquities and Near East collections were also added in 1888 (and a glass pyramid added a century later in 1989). This expansion required digging and excavation, which unveiled mysteries like a vaulted room beneath the Caryatids room…

To this day, there are vestiges of the Tuileries Palace not just around Paris, but the world; bits of stone and marble from the palace were sold by a private entrepreneur who zealously distributed pieces of the palace for profit. A group called the Committee for the Reconstruction of the Tuileries proposed rebuilding the palace in 2003, noting that much of the original furniture and paintings had been kept. Then president Jaques Chirac called for a debate on the estimated 300-million euro project. But it didn’t go forward, with the director of Architecture and Heritage, Michel Clément, saying in 2008 that “from our point of view, the reconstruction of the Tuileries Palace is not a priority. In addition, it is not part of French heritage culture to resurrect monuments out of the ground ex nihilo. Rather, we are concerned with the vestiges that have survived.”