In the decades since she jumped from a lower Manhattan high rise window at the age of 22, Francesca Woodman’s work has been rediscovered, revered and taught as gospel to photography students and has taken on a mythical cult status. Critics are forever tempted to use the circumstances of her death in 1981 as a key to unlocking her compellingly strange images riddled with ambiguity that – a bit like a psychoanalytical test, can affect beholders in different ways, depending on their melancholic state. The second week of September is National Suicide Prevention Week, an annual awareness campaign that often passes by quietly for most, and painfully for others. To help raise awareness about suicide prevention and warning signs of suicide, we’d like to talk about Francesca and share her ethereally visceral body of photographic work.

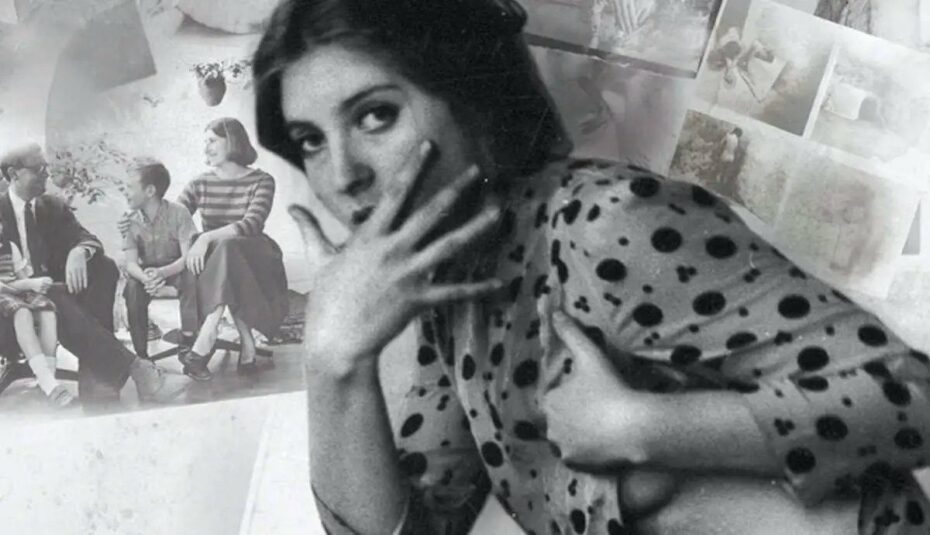

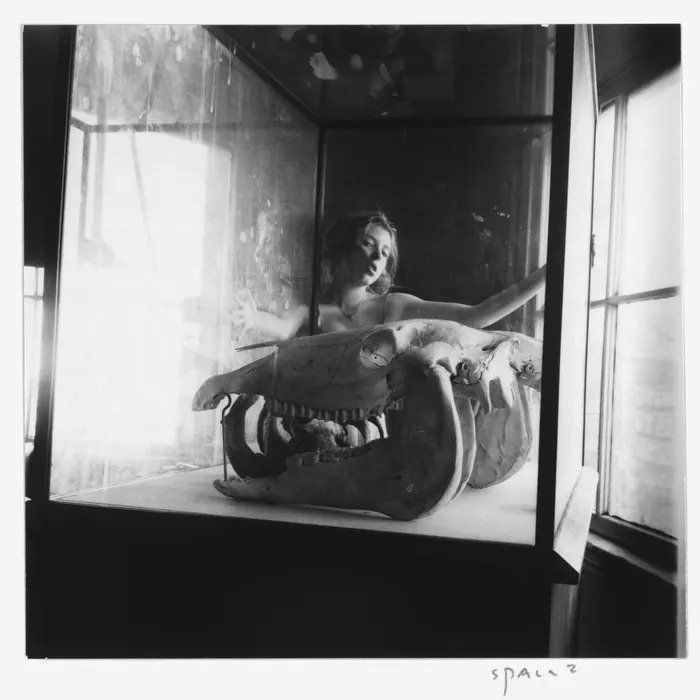

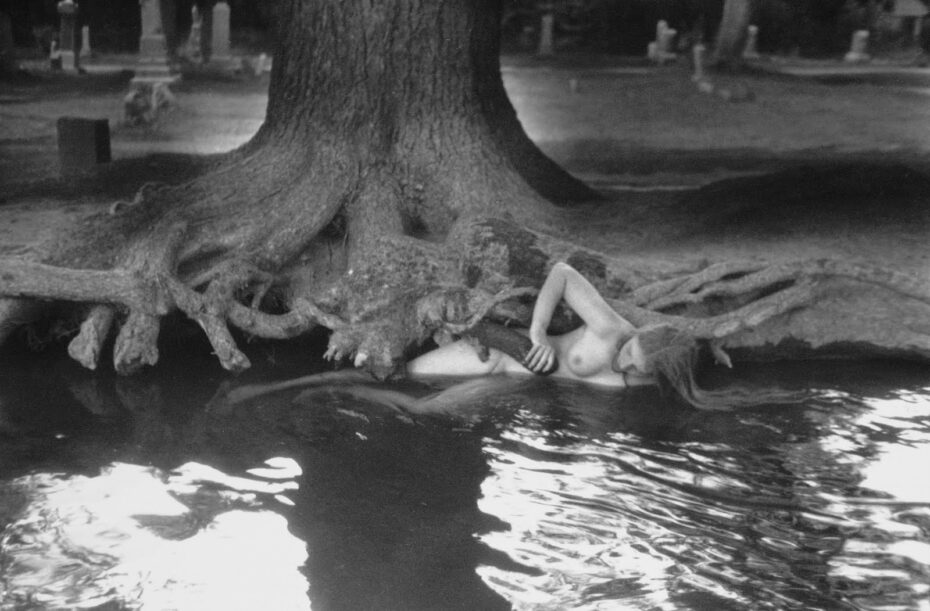

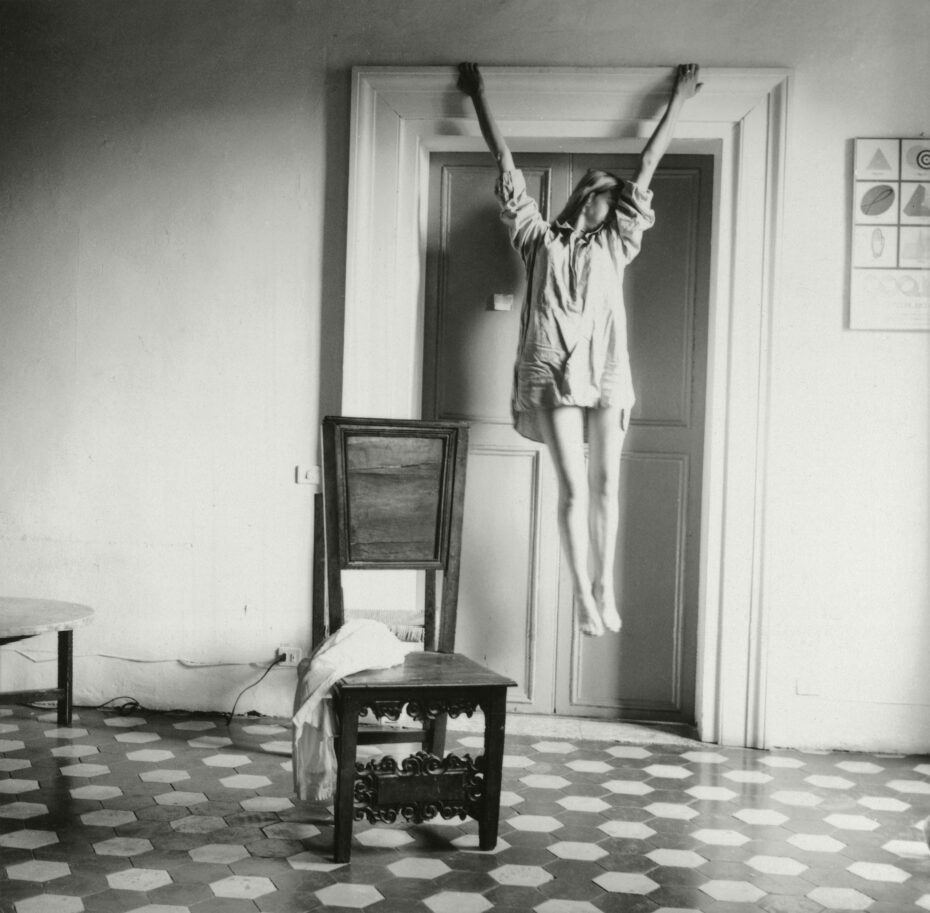

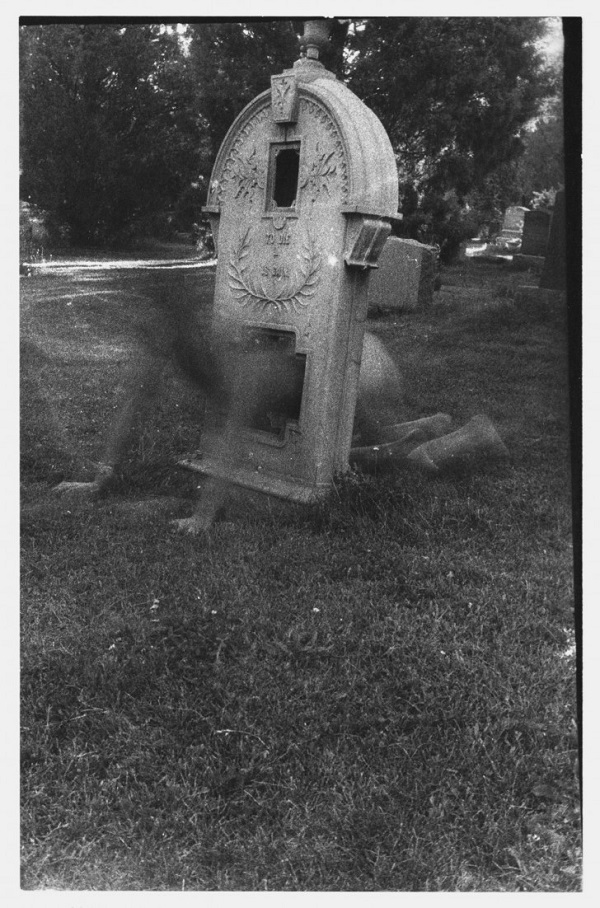

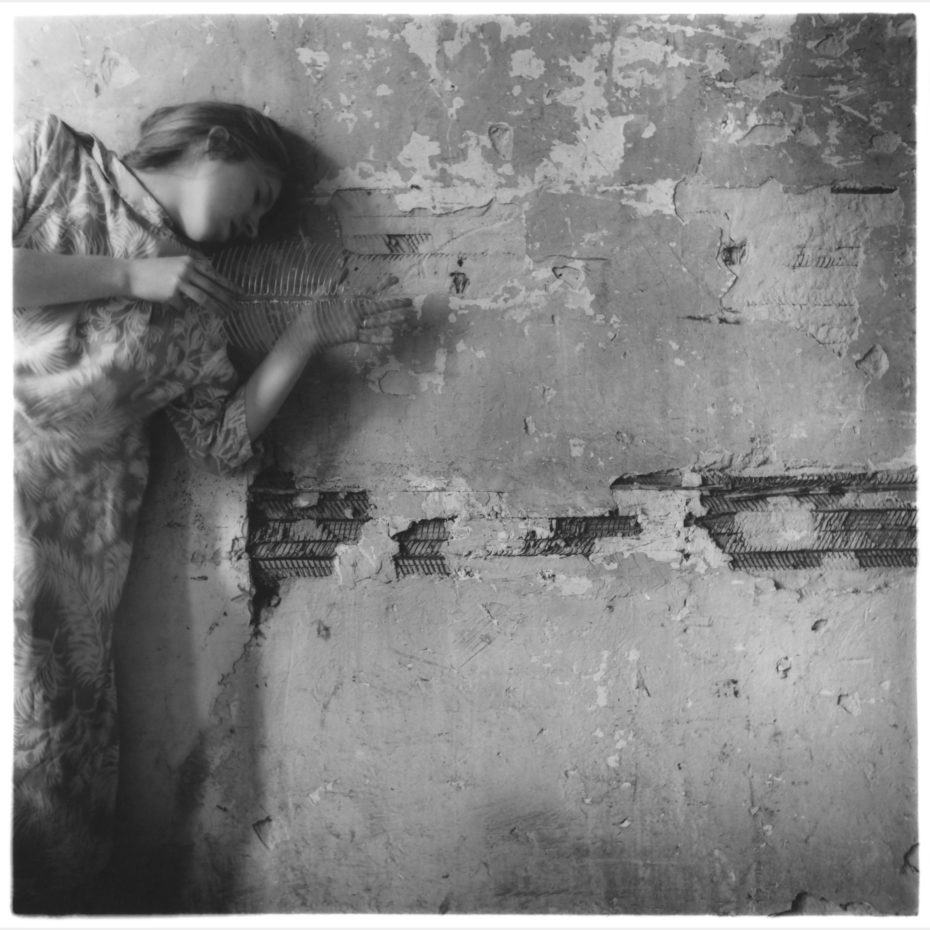

Woodman’s work has had a powerful grip on audiences. She left behind some 800 photographs inextricably intertwined with her own life and personal wellbeing, that still being dissected. To this day there are many questions that surround this exceptional artist. Much of Francesca’s photography features herself as the subject and protagonist; often she seems tormented, distressed and panicked, in despair, constrained, contorted and entrapped; her face a ghostly blur, her body deliberately depicted vulnerably nude or semi-clad. Like a piece of theatre – gothic and ghoulish – the subject in her scenes is found in graveyards, in abandoned houses, in decaying factories, in spooky natural history museums filled with jarred animal fetuses.

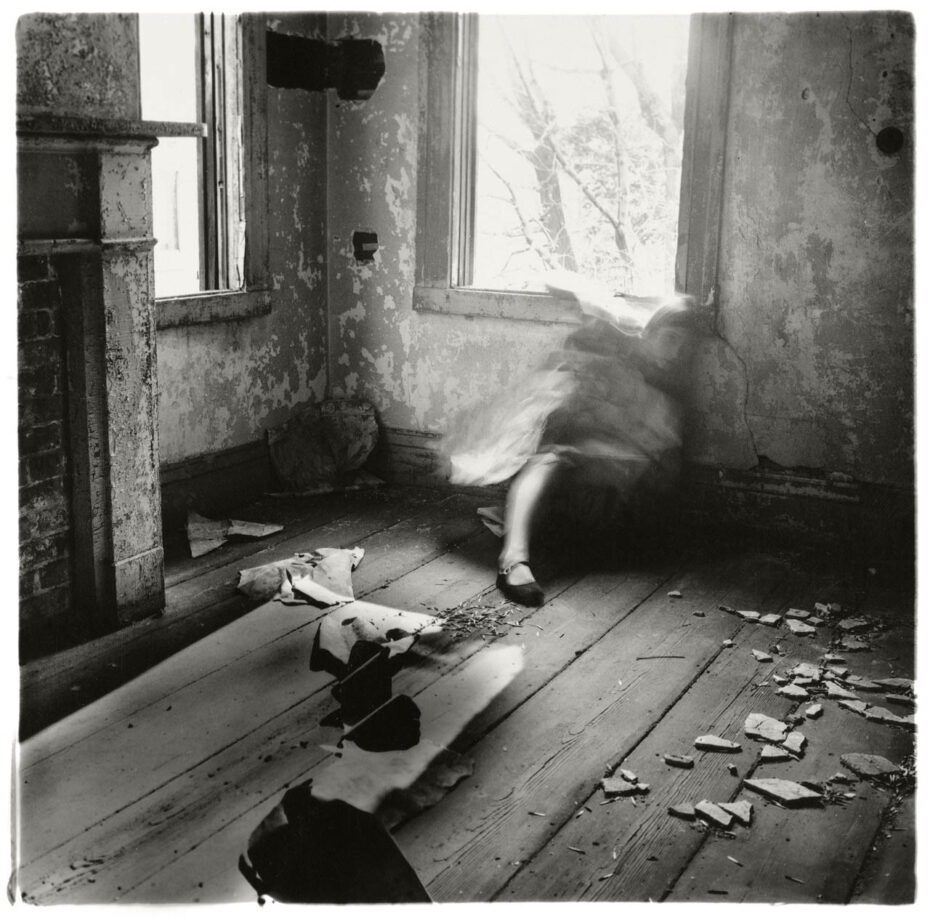

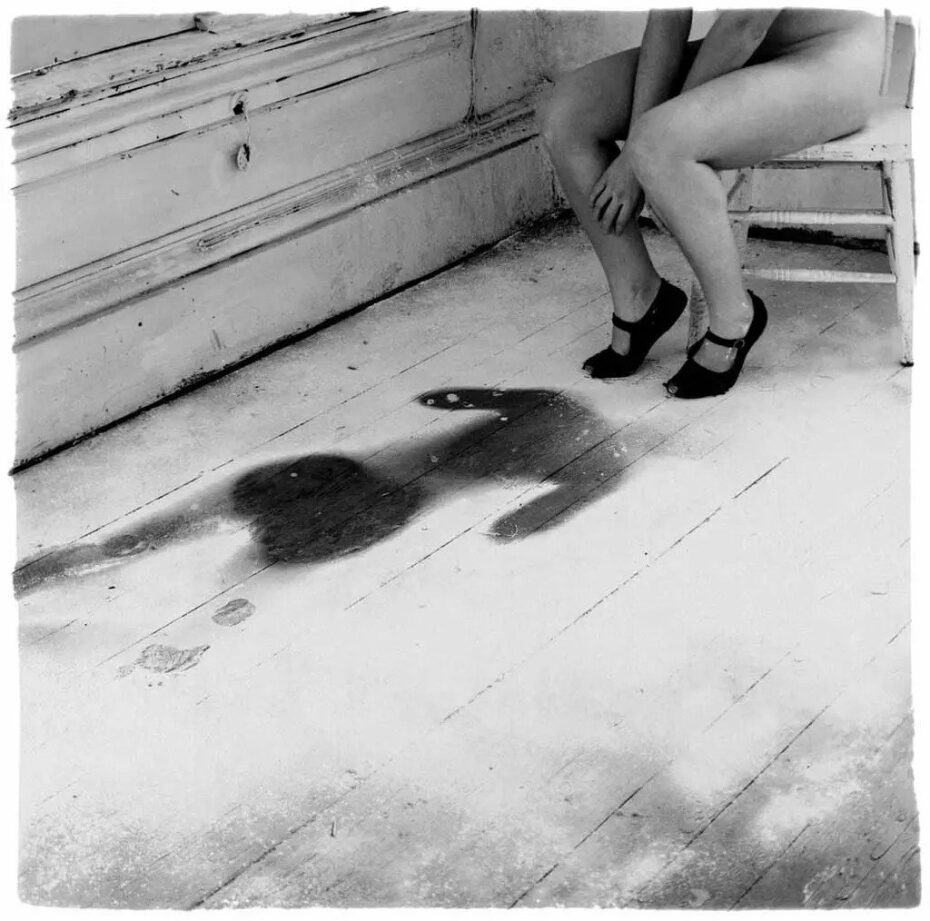

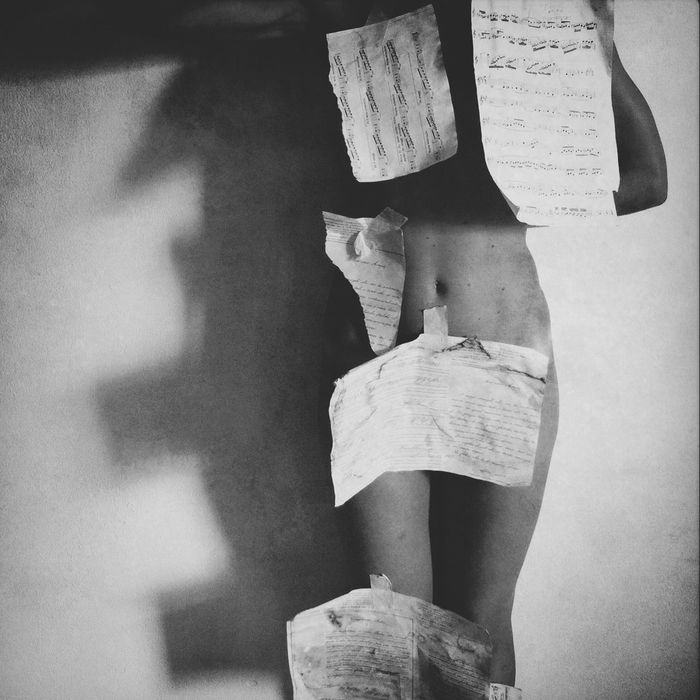

Often the nude female subject would disappear into ghostly smoke, she’d blend into walls and evaporate in the sunshine, reinforcing the rhetoric of a quest for erasure. We know that while she was a student at Rhode Island School of Design, her work showed the ‘engagement with the female body and her simultaneous courtship and subversion of the male gaze, in addition to her employment of highly charged symbols’, according to Corey Kelly in an essay entitled A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman. Much of it is photographed within the confines of a domestic setting – does that constitute a feminist outcry for the plight of women?

An article in Slate begged the question:

“Is Francesca Woodman the Sylvia Plath of Photography?”

Much guesswork remains and all we can do is to turn to the clues in the artwork themselves – or so we assume.

Francesca Woodman was born in Denver, Colorado, into a family of artists, her father George a university lecturer and painter, her mother Betty a ceramicist and according to Francesca’s brother Charles, “art was a religion. It was like a background, always there”. In the pursuit of art, the Woodmans bought a home at Antella near Florence where they’d holiday and work in summer and where a young Francesca would spend a solid year learning Italian and going to school when the family moved there for a sabbatical. It was also in Italy that her father first gave her a camera. Later (1978) she would return to Rome and study at the Rhode Island School of Design’s European Honours programme. Italy, balmy hot summers and intense Mediterranean light, was possibly the greatest singular influence on Francesca Woodman’s work, the intoxicating beauty and decay having provided the inspiration for her best known photographs.

The intense Italian light floods her images, blending the crumbling stucco walls with her soft curvacous body. Contrasting materials – brick and flesh, yet under the soft shadows all morphs into one. Crooked tables, shiny fish scales, paint-splattered walls all merge into her patchy body paint and dust, a visual harmony from so many competing and disparate elements, all in concert through the lens of her camera. The juxtaposition of the elements is dynamic: asymmetrical compositions and peeling plaster lines are abruptly stopped by her smooth skin, not jarring, all well under the gaze of her camera’s eye. Italy is where she conjured up some of her most memorable work: her world apart, her own special place.

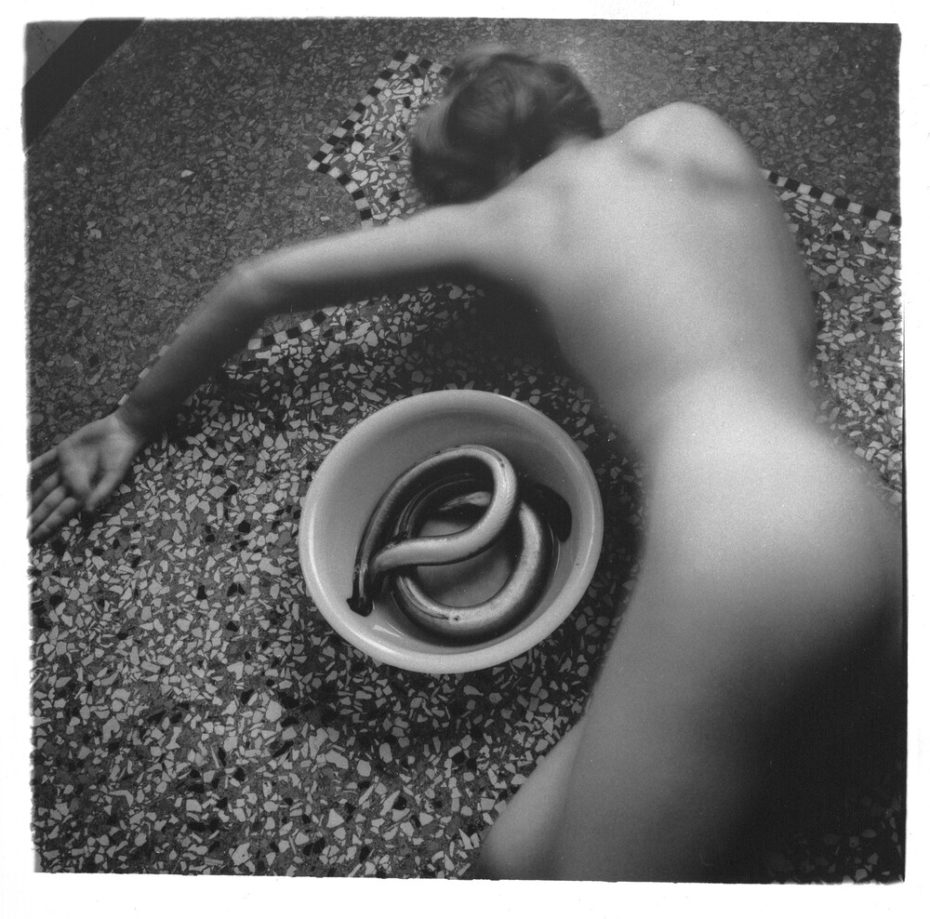

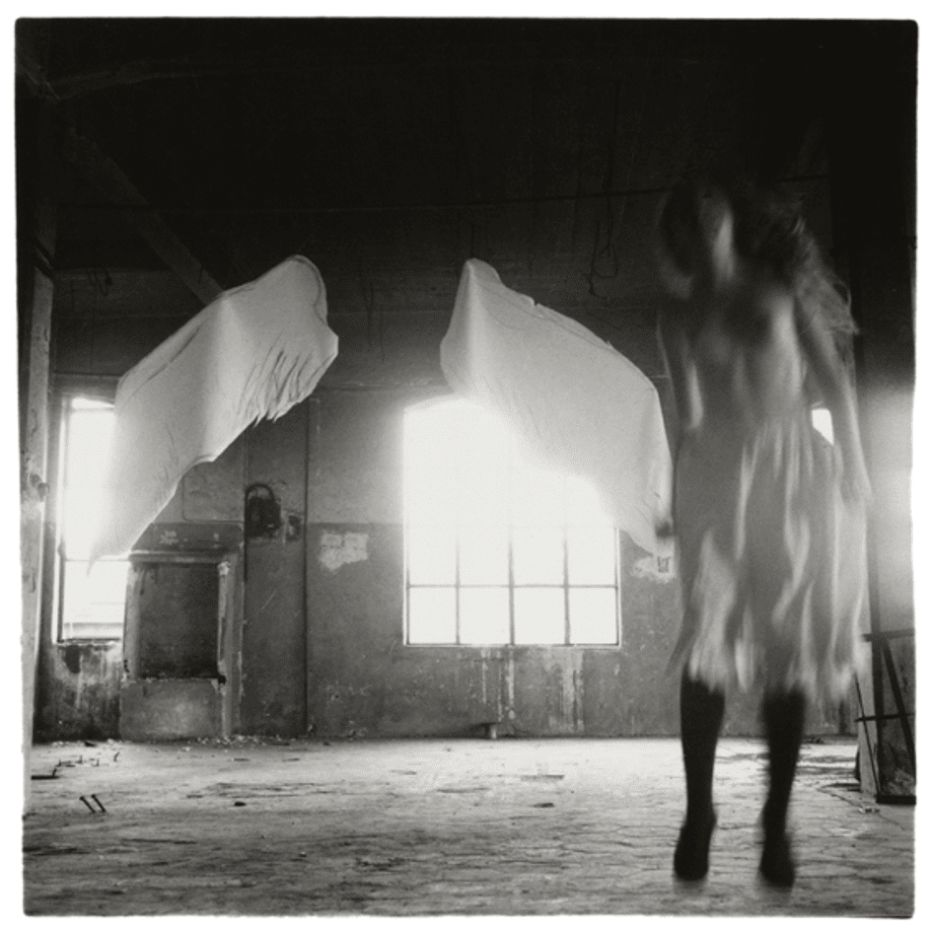

From her Italian stint came the Surrealist-inspired Eel Series (1977/8) featuring Francesca’s contorted body, slightly blurred and in soft focus, on the floor, turned away from the observer but facing a bowl of eels that she had bought earlier that day from a Roman market. It was in the Maldoror bookstore with its Surrealist, avant-garde literature where she spent hours, and also where she later held her first solo exhibition. An abandoned, dilapidated pasta factory with its peeling walls, the Pastificio Cerrere in San Lorenzo, became the space where she’d incarnate her imaginative compositions. The Angel Series sees Woodman leaping joyfully towards two wings hanging from the ceiling of the pasta factory. Here she would experiment with the disappearing forms, the ghostly figures blending into the furniture and the other characteristic elements that we now associate with her work, all retrospectively interpreted by some as a foreshadowing of her death.

Francesca Woodman would mastermind these photographic ‘stories’ that, some critics argue, were anything but spontaneous. They’d be carefully planned, staged and meticulously choreographed – much like a Surrealist artist would their painting or sculpture (Woodman was hugely influenced by the Surrealists Dora Maar and Man Ray). Such was the genius of Woodward that she would invite the viewer into her private sphere, as if we are party to her very intimate thoughts and allowed to see her at her most vulnerable. Francesca would both tempt and tease with her photographs; are they private, candid or exhibitionist? Many feel escapist, there’s evidently fun being had in the taking, while also being oddly erotic like the photographs with an eel draped between her legs and another pointing at her crotch. Others are disturbing part-bodies, her legs ‘amputated’ underneath a coffee table or her torso lost in a cupboard.

Her technical ability and darkroom skills were those of a magician. An accomplished photographer at an uncannily young age already, her black and white self-portraits (or models that resemble Woodman) with long shutter exposures, lens flare, double exposures and Victorian ‘spirit photography’ are a common thread that runs through most of her work. Francesca Woodman knew exactly what she wanted to accomplish with each shot, like the best film director she would orchestrate every scene to serve her narrative. She’d manipulate her compositions, shadow and light and timing, with meticulous precision. She embraced the notion that photography was an art form full of illusion, delusion and surprise – what the human eye sees, the lens doesn’t necessarily, what happens before or after the shutter snaps open and shut, remains a mystery.

She was drawn to collecting rafts of theatrical textile props – fraying textured bedlinen, shaggy furs, stuffed animals, dead birds, pieces of furniture vintage clothing (she had a brilliant eye for frocks) – that she cleverly inserted into scenes. Her stories were often, deliberately, half told, figures were half in dark, half in light, faces and hair fuzzy and vague, and we, the viewers, are invited into the scenes – but only some of the way, never fully. That’s part of the charm of Francesca Woodward’s work – their interactive, interpretative quality, that nothing is quite what it seems.

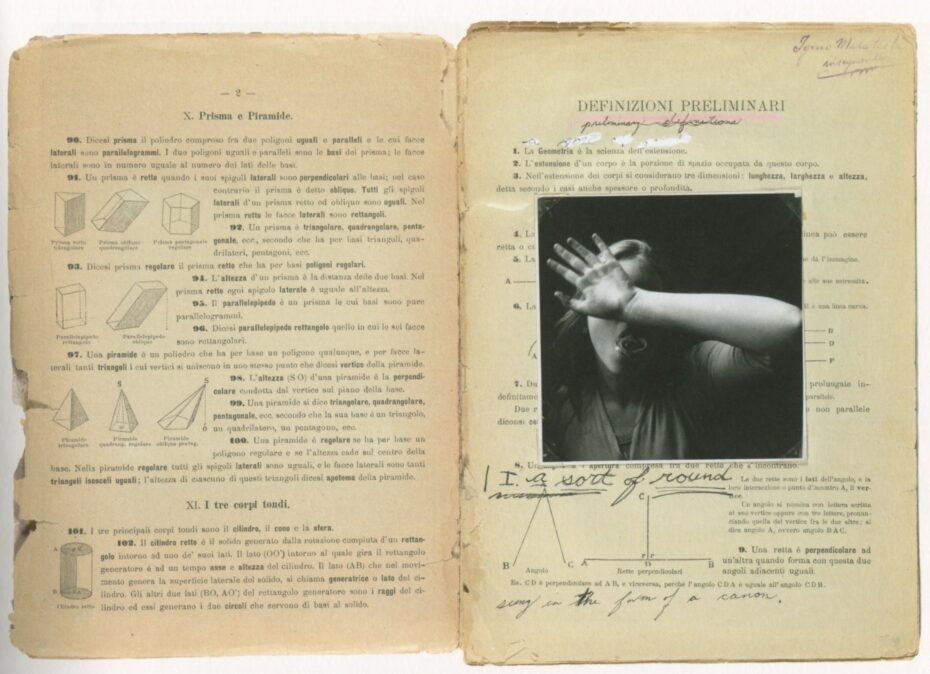

She had been experiencing bouts of depression after returning to the USA and New York in 1979. She worked part-time as a photographer’s assistant, she suffered a romantic break-up and at the same time, was upset that her work wasn’t gaining adequate attention. Despite these warning signs, those close to her didn’t anticipate what was to follow. Perhaps the only omen came from Alex Riding, who thought that in constantly pushing herself to the limit to explore perplexing subject matter, she was “unaware of the dangers involved, like a moth flying ever closer to a flame”. In 1980 she was offered a summer fellowship at McDowell Colony in Peterborough, where she had a darkroom and produced profound work. In 1981 one of her notebooks that she’s been working on since adolescence was published in book form, Some Disordered Interior Geometrics.

It may indeed be the case that her work had been acutely influenced by living in a state of constant anxiety. We know she had a penchant for reading Gothic literature, rich with derelict buildings, tombs, mirrors and angels with female protagonists imprisoned for ‘madness’. Her brother Charles Woodman, like her parents, thinks it’s not right to draw parallels between his sister’s work and treat them as ‘suicide notes’ – “it’s not the lens I see it through”, he says. In a documentary made decades after her death, a school friend remembers that in the weeks before her death, she ceased to produce photographs altogether, and thought that instead of fueling her creativity, a debilitating depression seems to have halted it altogether.

Her parents recall a witty, amusing girl who wasn’t particularly intellectual, who liked having a good time. Her critics and fans see a tormented, sad, lost girl whose depression played a major role in her art. Her portraits reveal a vulnerable, painfully honest, neurotic, at times humorous and somewhat ironic but always artful soul. Her mother muses, “Her life wasn’t a series of miseries. She was fun to be with. It’s a basic fallacy that her death is what she was all about, and people read that into the photographs. They psychoanalyse them. Young people in particular feel she’s talking about them, somehow. They see the photographs as very personal. But that’s not the way I approach them. They’re often funny.”

Ultimately the mystery that surrounds Francesca Woodman is what intrigues us as much as the inimitably aesthetic and nostalgically precious body of work she had left behind. In the final journal entry before her ultimate, personal journey out of this world, poignantly written in the past tense, she wrote, “I was inventing a language for people to see the everyday things that I also see, and show them something different.” Francesca’s world was that of a divine light that bound and blessed all that it fell upon and she captured this in her camera’s eye. Unfortunately in the real world, nothing is quite so easily controlled. Perhaps that was Francesca’s biggest gift to the world – to be able to see the harmony in chaos and present it to us as something beautiful.

A book now available from the library at Messy Nessy’s Cabinet: