When we think of Vogue we visualise a vibrant, striking, photographic image adorning the front cover of the seminal publication, but the first pictorial cover would not appear until 1932. Before the likes of Helmut Newton, Richard Avedon, Annie Lebovitz and Steven Meisel, it was the time of the illustrator. Early 20th century artists George Wolf Plank, Georges Lepape, Eduardo Benito, Helen Dryden, and André Édouard Marty, among others, would transform fashion and help elevate Vogue to the pinnacle of sophistication.

Vogue had been founded by Arthur Baldwin Turnure and published its first weekly Journal in 1892. It would be advertised as a cultural periodical aimed at high society and the social elite. The illustrated covers and contents would be a traditional take on the figurative form. Images were rendered by illustrators and then etchings were made to produce the ‘fashion plates’, to be used to mass produce the artwork via the printing press. Fashion plates had been used since the late 16h century to depict the latest trends at the Royal court. But it wouldn’t be until the 18th century that it was widely used and distributed to the general public. Vogue’s first editions were prominently black and white as colour printing was still in its infancy on a large scale while coloured prints had been laboriously hand-rendered in the past by designers of the day to try and express the vivid colours of their creations. In 1909 when Condé Montrose Nast purchased Vogue, it began its transformation into the iconic visual identity we now know.

Nast’s changes would include a move to a fortnightly, then a monthly format. The price rose and so did the quality, the magazine centered on high society, Haute couture fashion, and the lifestyles of the upper echelon. Nast, sought out and employed the finest illustrators and artists of the day and with the advance in printing techniques, the magazine’s aesthetic metamorphosis would begin to evolve. The early part of the 20th century would become the golden age of the Illustrator at Vogue. Visual artists with their own personal perception of form, line, and colour would bring their character and vision to produce some of the most celebrated illustrated magazine covers ever produced.

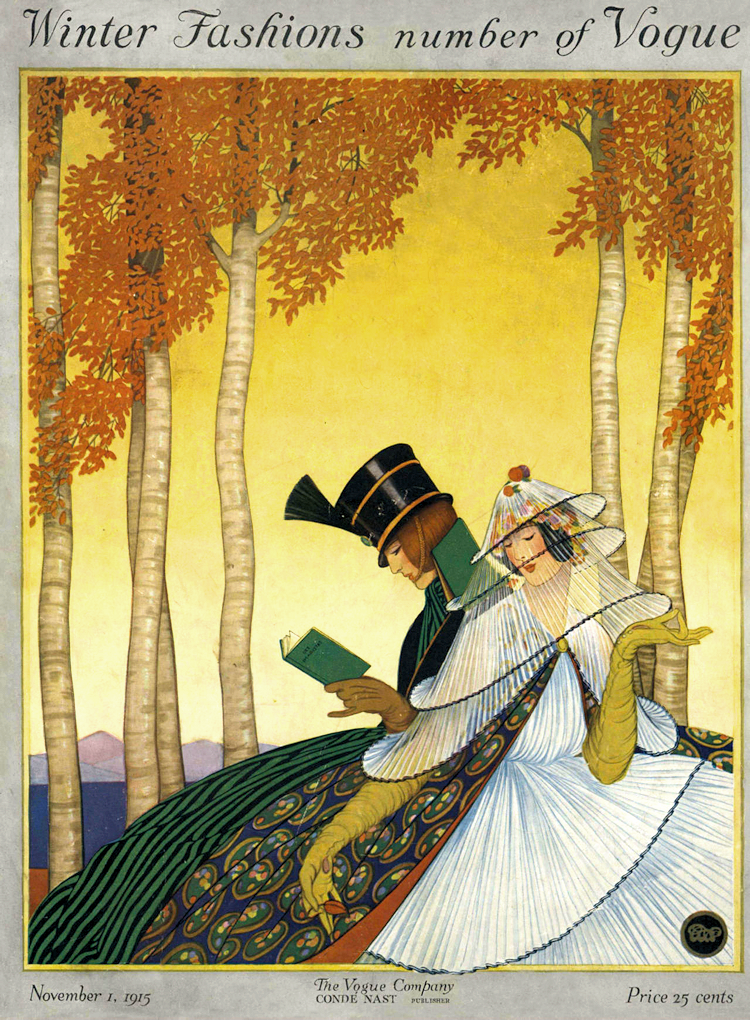

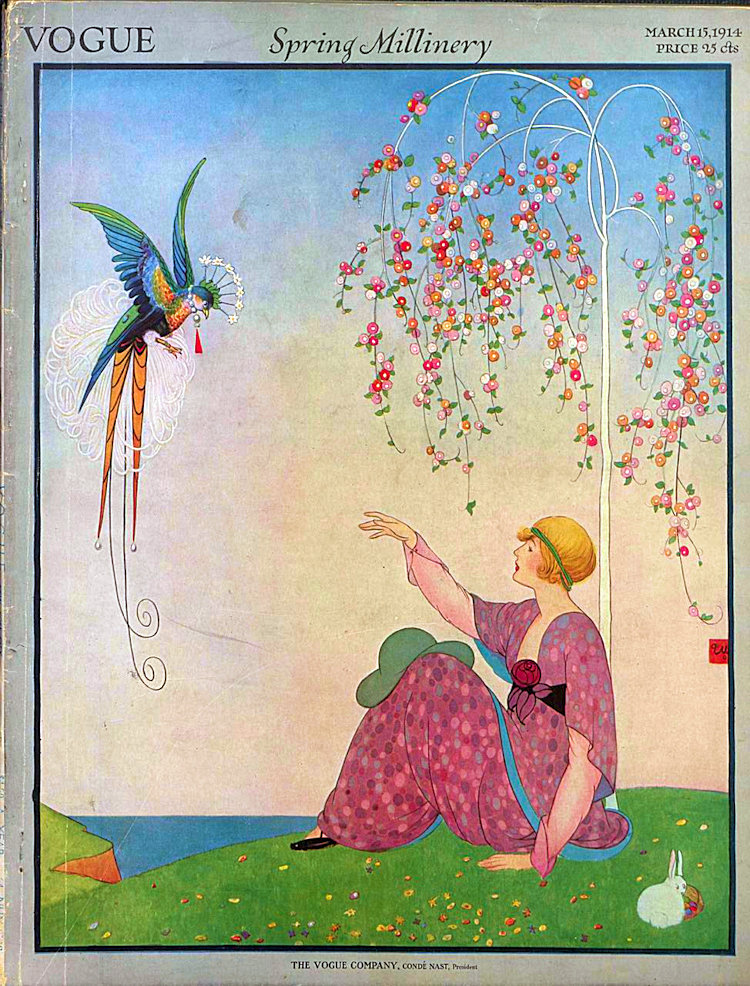

George Wolfe Plank began to work for Vogue in 1911, with his first cover appearing in November of that year. The woman joined with the peacock would be a step towards a new dawn in fashion illustration. The image shows the eastern influence that was prevalent in the Art Nouveau scene at the time.

Japan had opened up its borders for the first time in the late 19th century and woodcut prints that had appeared in Europe had influenced artists such as Van Gogh, gauging and Toulouse Lautrec. The technique of block colour and nominal use of perspective gave the image a flat defined stylistic approach, an imaginary world where fantasy and elegance are intertwined. This first cover Illustration would prove so popular it was reproduced for the later 1918 addition. Plank was a self-taught artist and before he could monetise his considerable talent he had worked in factories and department stores. Plank would produce over 60 covers for Vogue over a period of 15 years.

Watercolours, Inks and Gouache were employed to produce an ethereal, through the looking glass aspect to his surrealist fashion illustration. Elegant Figures were elongated and draped and paired with objects and animals, exquisite detail is juxtaposed with blank space giving an arresting effect. In his November cover of 1917, you can witness his use of negative space and vibrancy of crafted detail in the garments of the figure. Post Vogue, he lent his practice to include Book Illustration, Textiles, and theatre production, living in England until his death in 1965.

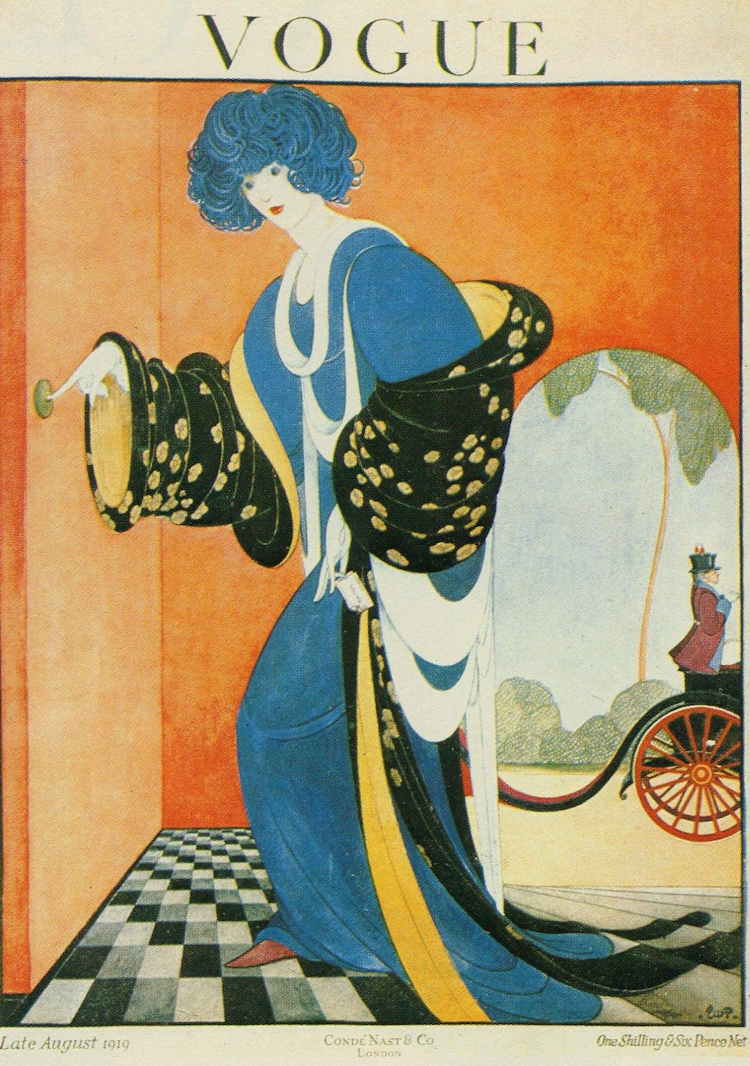

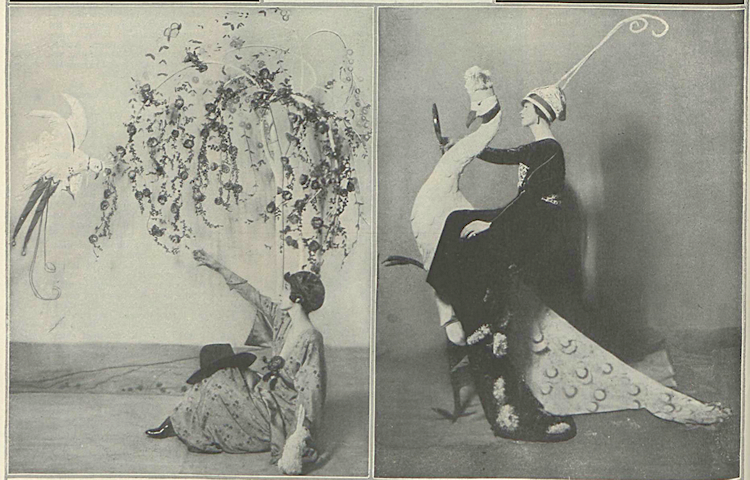

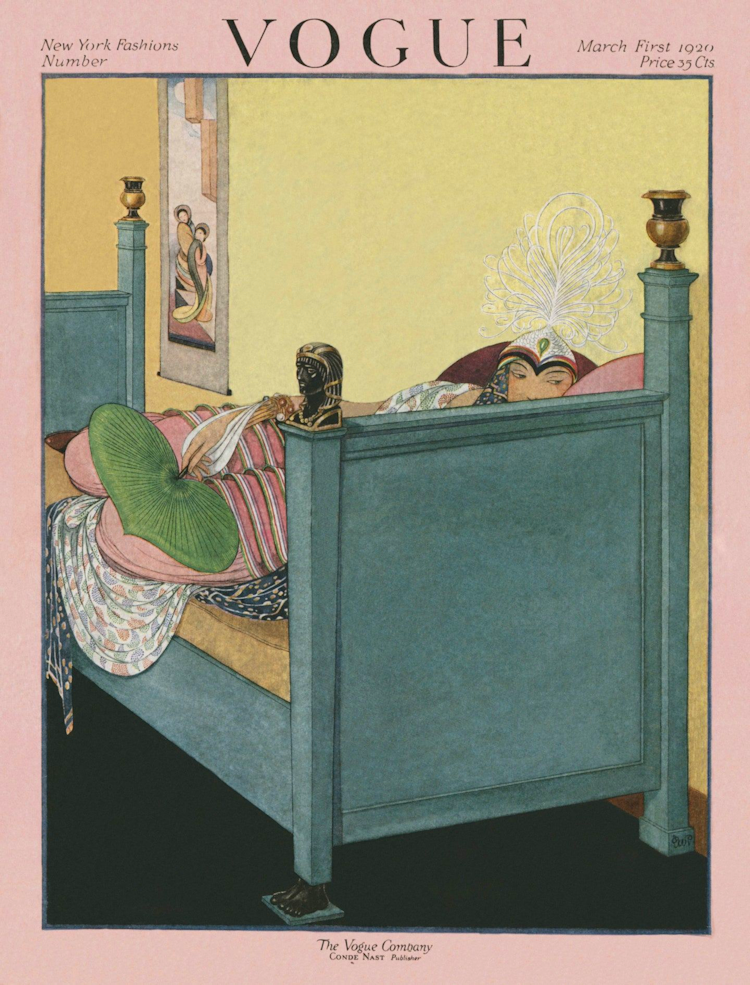

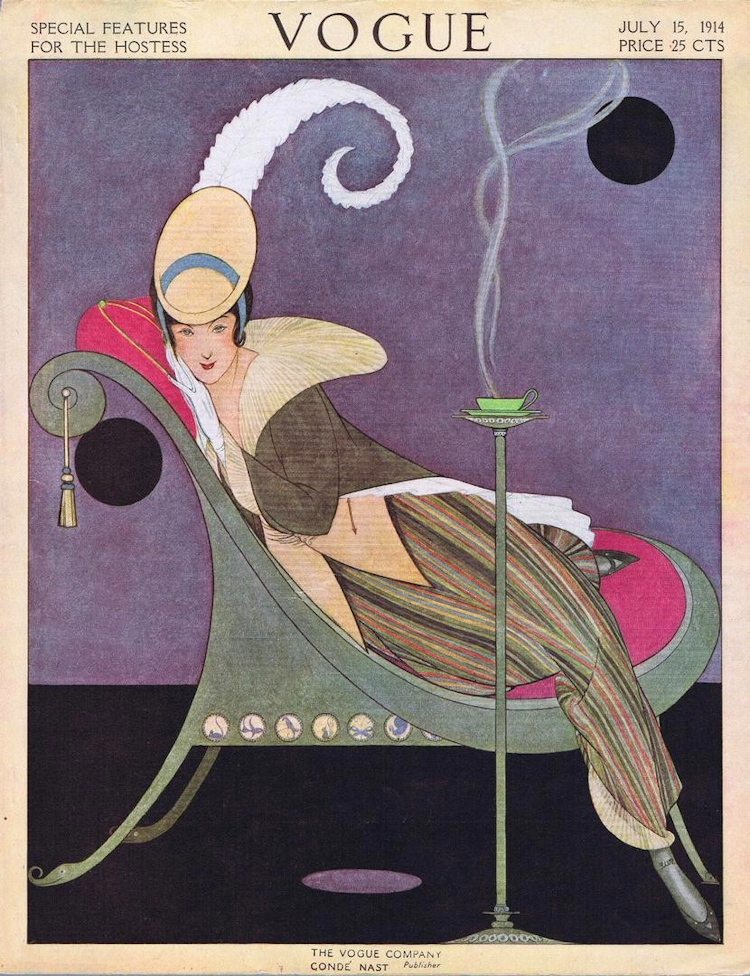

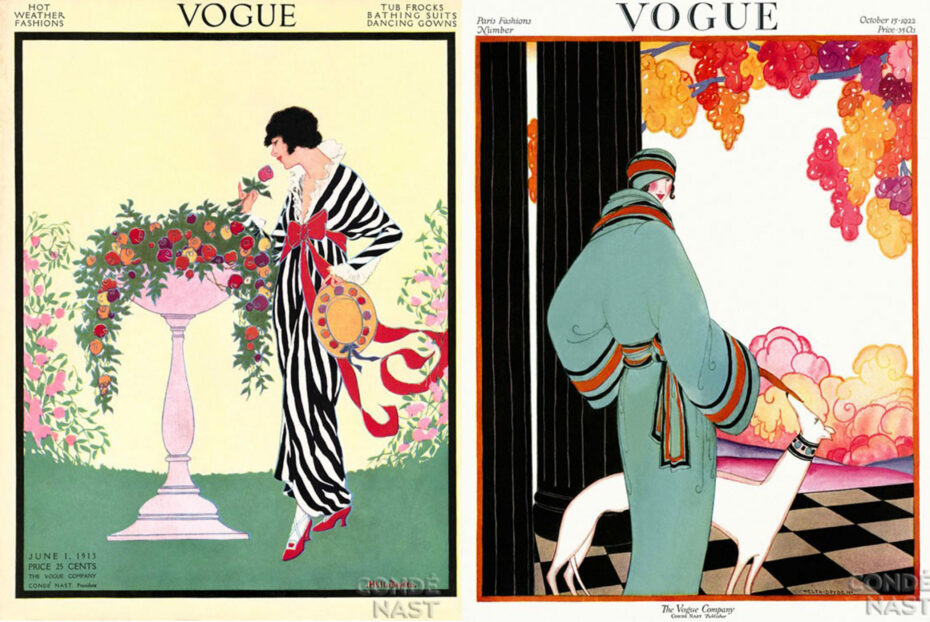

Helen Dryden was born in Baltimore in 1882 and, as with George Wolf Plank, she was largely self-taught; she had shown early promise when she had designed paper dresses for her dolls. These would be eventually sold to a newspaper for their fashion section. The early work of Dryden shows a sensual impressionistic quality of light and colour with a decorative flair, one of her inspirations had been the Russian painter and costume designer Léon Bakst who had recently transformed the Ballets Russes in Paris. Dryden began working for Vogue in 1919, she had been trying unsuccessfully to secure a creative position in fashion magazines for some time. But her drawings had been rejected by a staff steeped in inequality and ignorant of her talent.

When Condé Montrose Nast took over the magazine, he recognised Dryden’s artistry and originality Their collaboration would continue for 13 years with over 100 vogue Covers and illustrations with Dryden going on to become the highest-paid female commercial artist In the United States. Dryden would develop her style at Vogue transitioning from decorative Art Nouveau to the geometrical Art Deco. The artist’s progression can be seen through her covers from 1913 to 1922, Dryden will always be associated with the Art Deco movement as this was when her style flourished at the magazine. Her figures of women could be seen in contrasting imagined landscapes of sharp structure and tinted flora, sometimes with animals whose colours and elongated forms complemented the figurative focal point of the cover.

Dryden left Vogue In 1923, when her practice was moving towards a more cubist influence as can be seen in her later work for The Delineator, a prominent women’s magazine of the era. Later she would work in Industrial design for the American car company Studebaker designing car interiors showing what a versatile and innovative artist she was.

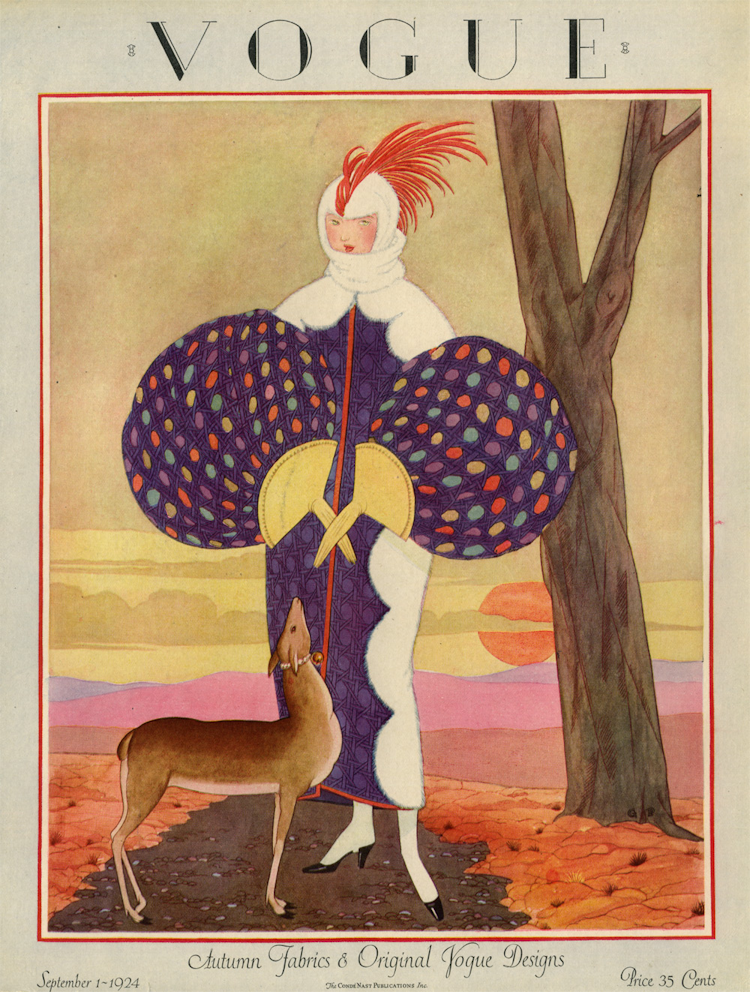

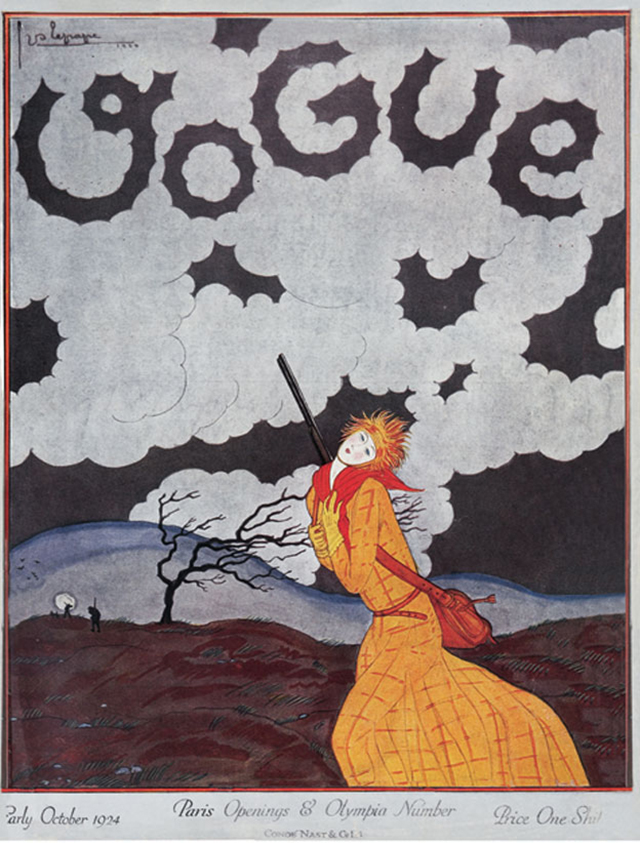

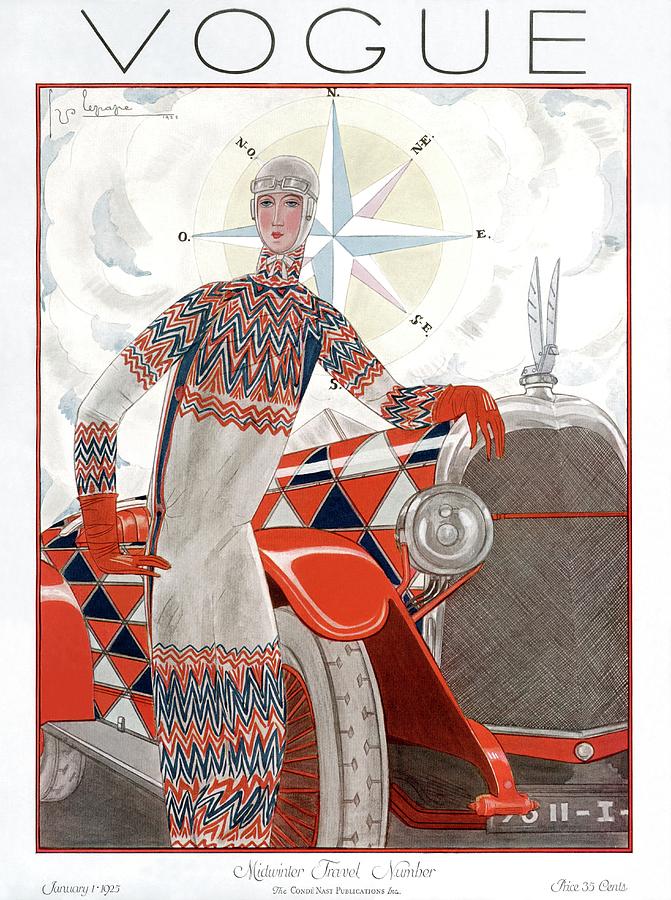

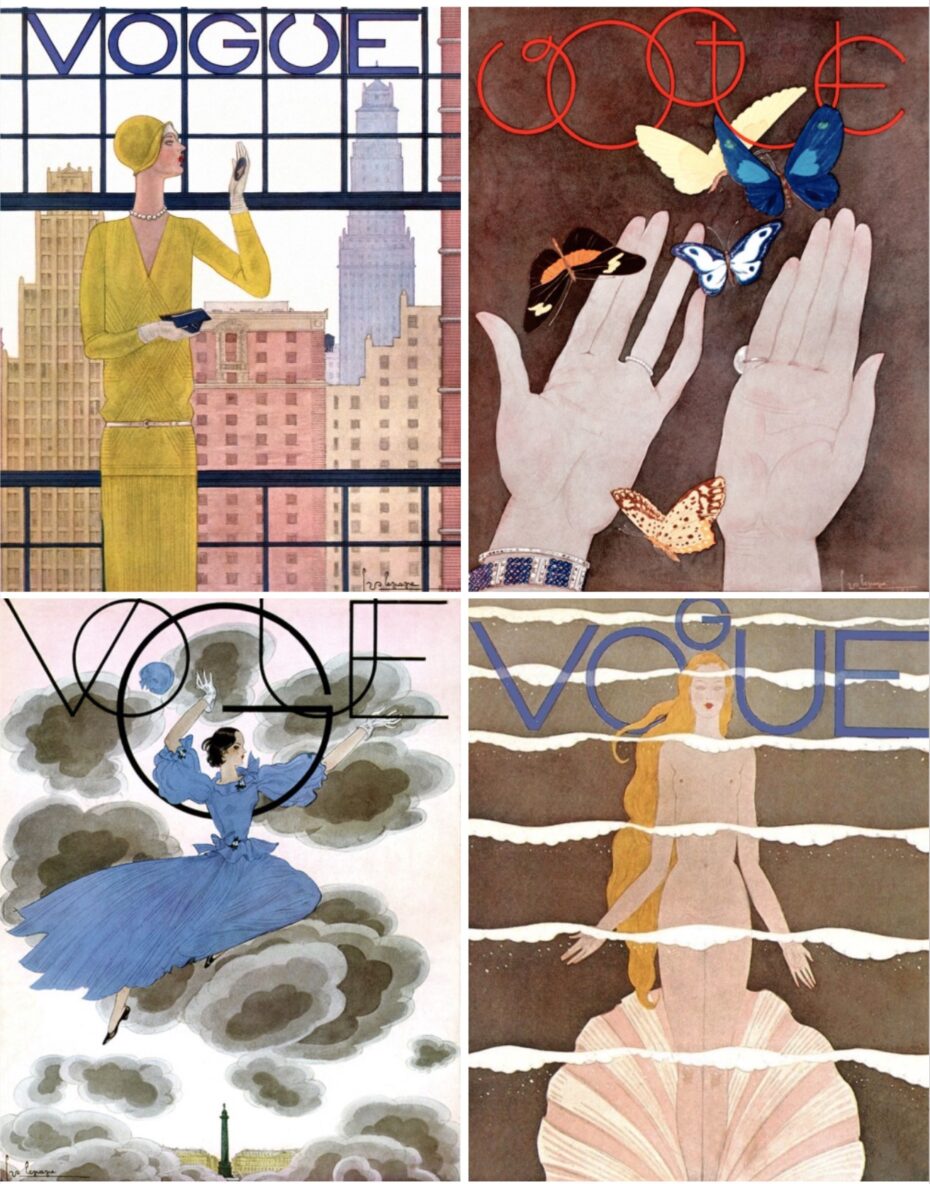

Movement, story, and exoticism would be some of the elements Georges Lepape would bring to fashion Illustration when Condé Nast invited him to New York in 1926 to work for Vogue. His work with fashion designer Paul Poiret over 10 years illustrating his collections was highly commended and led to work with the fashion magazine La gazette du Bon Ton, Harpers Bazaar, and various fashion houses and brands. Lepape’s output was prolific; he designed posters for film, theatre, costume, set design and textiles. In 1916, he illustrated the cover for British Vogue, the first of 114 covers he would complete over 23 years of collaboration with the magazine.

In 2016 a Vogue cover illustration created by Lepape broke an auction house record in New York when it sold for $52,500 after it had been valued at just $6,000. So what makes his work for Vogue still so significant now? The imaginative poetic gesticulation of his figurative characters gives a sense of narrative theatre to his work. His models live in his illustrations and don’t just exist in the flat of a two-dimensional landscape; they arrive and depart, flowing through a real and imagined world of the artist’s making. The environments can either sit in muted time or propel the foreground into startling intensification. On occasion, Lepape’s Illustrations would grace the covers of Vogue in New York, Paris and England simultaneously showing the vast popularity of his work.

Lepape’s covers would become highly anticipated by the public; he seemed to grasp a fresh approach constantly through his use of form, colour, his modern take on typography and the satirical element he would bring to the work. Lepape would continue to work for Vogue until 1939, always refining and innovating his unique style of illustration. He would continue to be a popular and influential artist until his death in 1971.

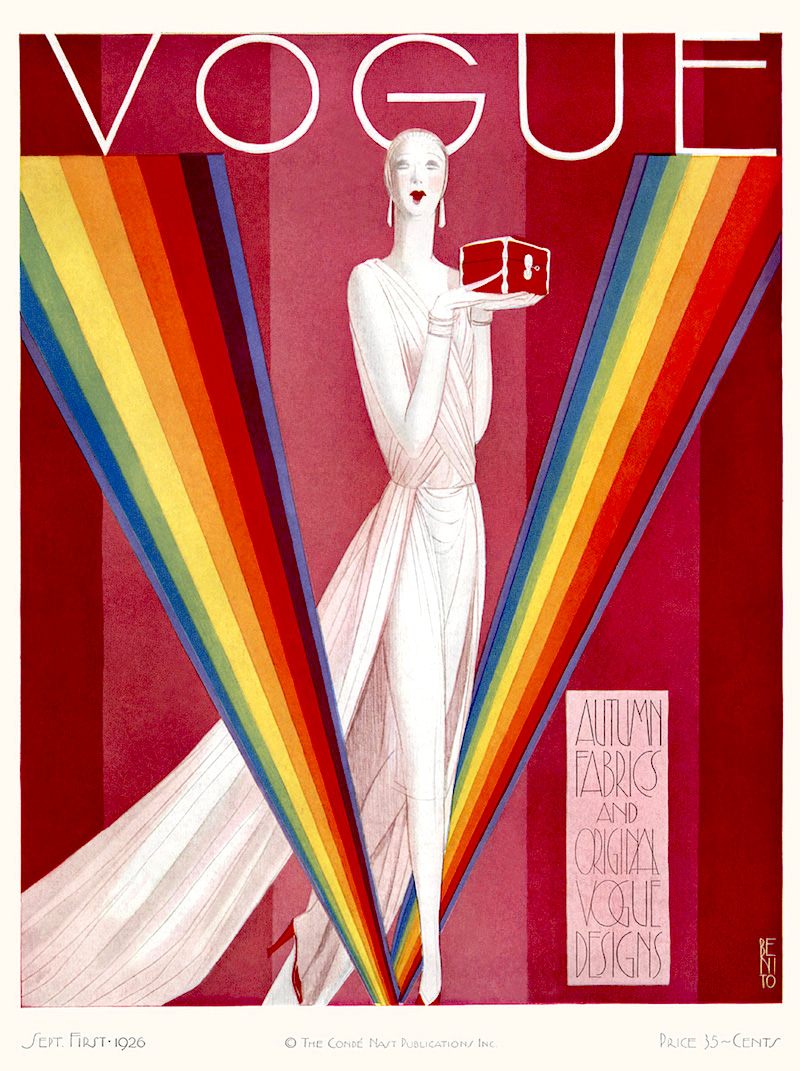

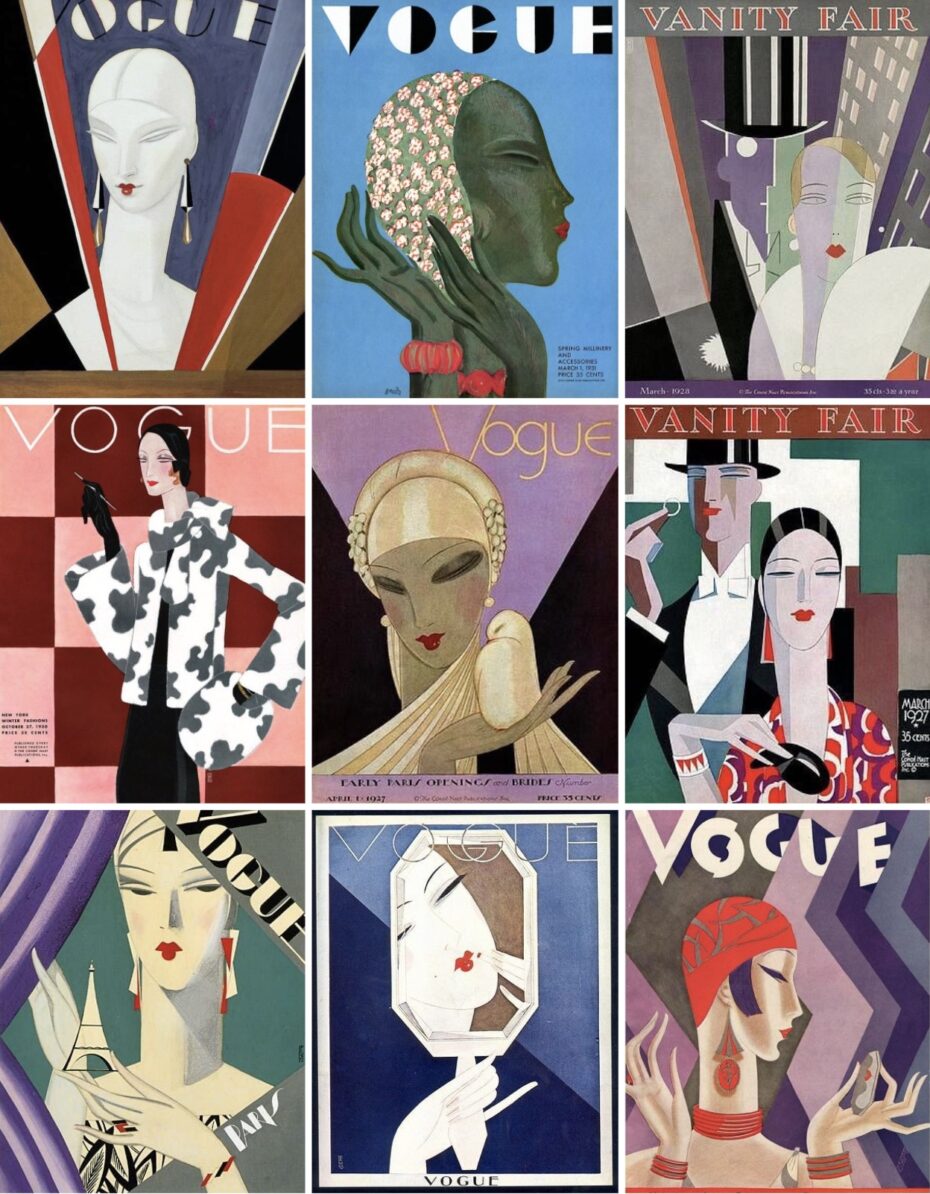

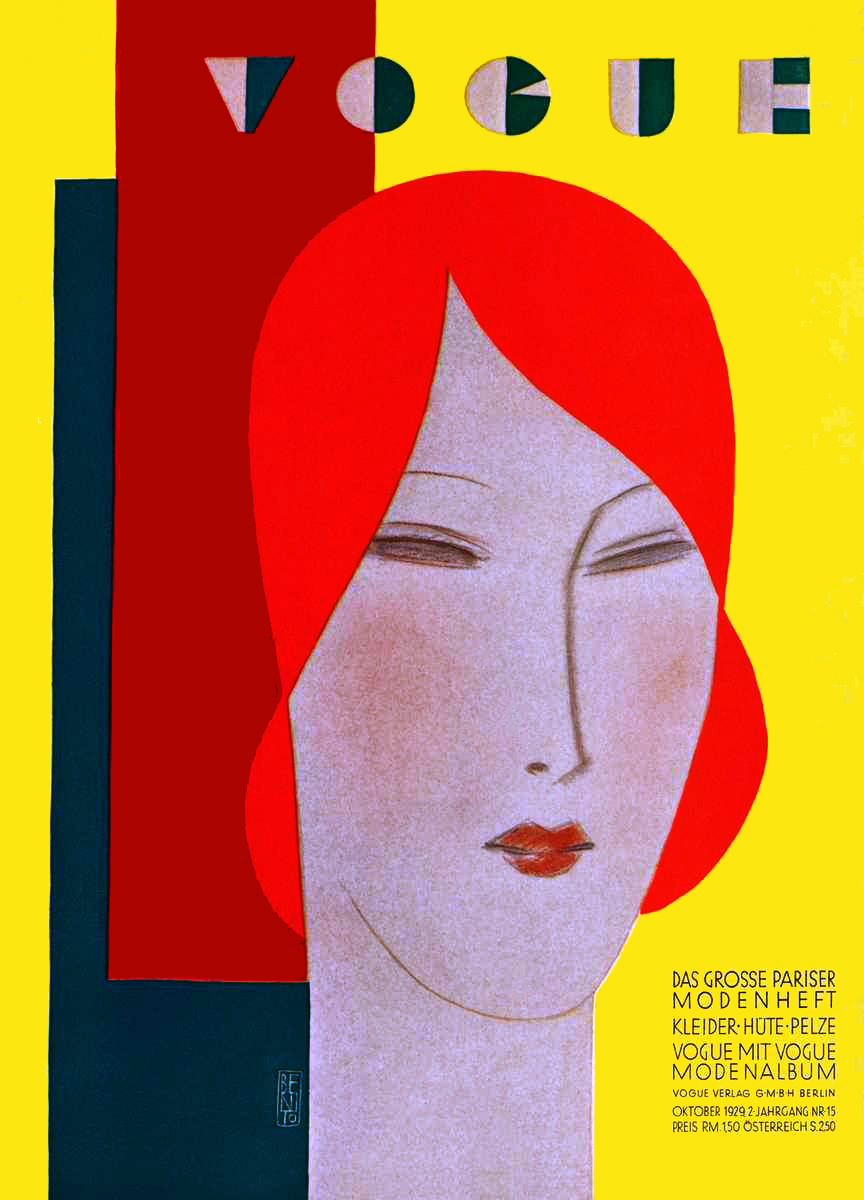

Eduardo Benito was born in Spain, studied art in Paris, and would be appointed ‘illustrator in Chief’ for Vogue in New York in the 1920s. His style would be influenced by the progressive art scene in Paris at the time, the Cubist sensibilities of Picasso and Braque would shape his attitude towards perspective and abstracted form in his illustrations.

In 1919 Benito exhibited his work in Paris at the Galerie Sauvage, and as fate would have it met the fashion designer Paul Poiret who championed his work to Condé Nast. Benito began traveling to New York and working for Nast at Vanity Fair and Vogue. His first cover would be in 1923 and his difference in style is evident compared to the other covers of that year. Benito’s Illustrations have more in common with some of the fine art paintings popular at the time. In an exploration into a geometrical concept of the human form, figures were often seen in flattened a close-up perspective, a modernist view of a decadent culture. Benito was an influence on the Art Deco movement of the time but his work for Vogue progresses toward a more Cubist ideology; a defined colour palette and his gradual use of shade and light to hint at depth in an abstracted scene.

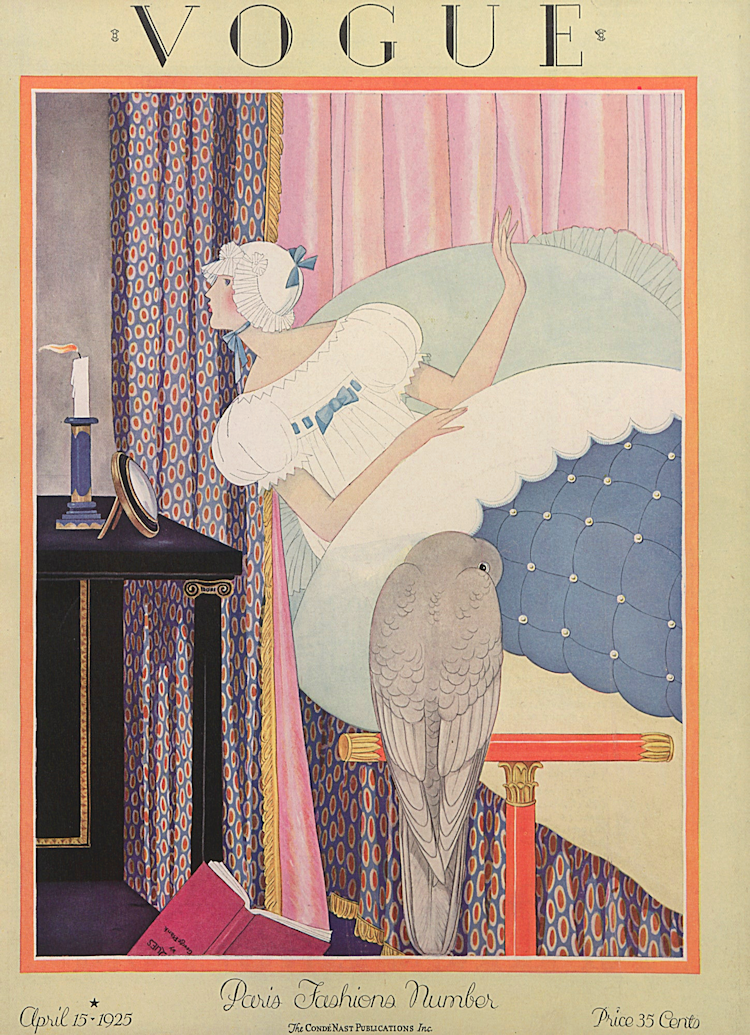

Many of Benito’s Vogue covers concentrate on the portraiture depiction of the female figure; models apply lipstick or gaze into mirrors, they hold drinks and trinkets, their large heads link to sinewy extremities that flow through the paintings. Benito would go on to work for Vogue for 2 decades where his innovative illustrative style was much celebrated then and now. He continued to work as an artist throughout the rest of his life passing in 1981 at the age of 91.

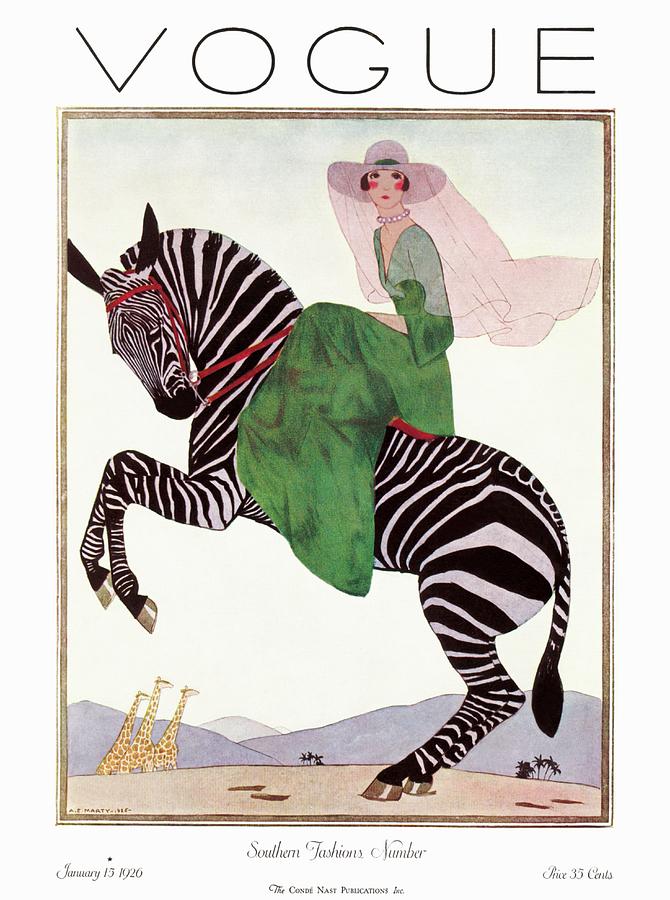

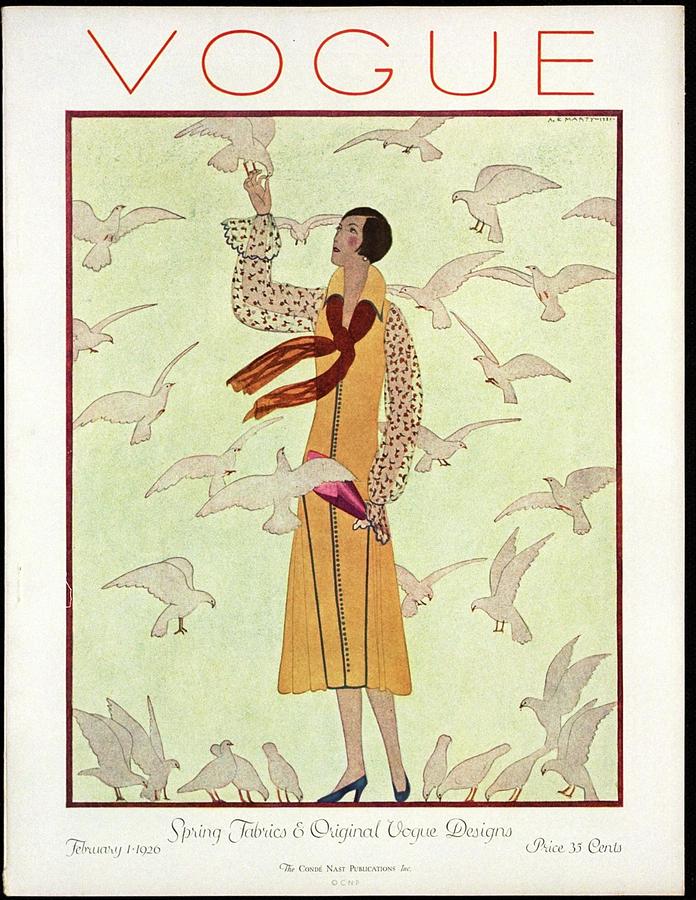

The visual narrative of André Édouard Marty’s work is what makes it differ from the other fashion illustrators of the time. Though keeping with an Art deco influence and sensibilities, Marty’s work dwells inside a domain of romanticism and ethereal elegance. André Édouard Marty was born In Paris in 1882 and would like so many others, attend the Ecolé des Beaux Arts in Paris, where he would meet amongst others, Georges Lepape. In the early 1920’s he would join the creative elite at Vogue, bringing his unique take on fashion illustration. Over a long career, Marty illustrated over 50 books, design ceramics, theatre costume, and set design and jewellery.

The story and theatrical element that exists in Marty’s illustrations take the viewer on a exaggerated tour into the fantasy life of the sophisticated. The blending and use of colour give the illustrations a lived-in personality, a life beyond the cover; a life of music and fashion in the cultural dynamism of the 20s. In a long career Marty would also be published in, Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fair, Le Sourire , Modes et Manières d’Aujord’hui and Comoedia Illustre.

The golden age of illustration would eventually succumb to the golden age of film. The glamour of Hollywood and the film industry in the 1930s had helped usher in the time of the photographic image in many forms. Edward Steichen, who had first had his fashion photographs published as early as 1911, would capture Vogue’s and the public’s imagination with its first pictorial cover; a full-colour fine art print that would announce the future to come. Technology had advanced making the camera and photography an almost instant medium. No more waiting on the illustrator to deliver their latest take on cultural creations, photographic fantastical realism was in vogue, literally. By the end of the 1940s the illustrator had largely been edged out of fashion magazines. The very thing that had helped create Vogue would now be side-lined to the more popular medium. Illustrators would still find work outside of fashion and with the magazines as art directors, but the influence and prominence of the hand-rendered image had waned and the last illustrated Vogue cover would appear in 1958. Art and technology, as with fashion, would be constantly evolving and changing but as trends are forever in a revolution of the past to influence the present, the first new illustrated Vogue cover in over 60 years appeared In Italian Vogue in 2020. It was 1 of 7 covers commissioned by the editor in chief Emanuele Farneti, as much for environmental issues as aesthetic. The sheer scale of a photographic shoot was highlighted by Farneti in the September issue.

‘’One hundred and fifty people involved. About 20 flights and a dozen or so train journeys. Forty cars on standby. Sixty international deliveries. Lights switched on for at least ten hours non-stop, partly powered by gasoline-fuelled generators’’

So can illustration remerge as the prominent visual representation of fashion and culture in Vogue? It would appear that it would be an ethical choice in regard to the environmental landscape. Technological advancement would be part of the cause for the illustrator’s decline in the mid-20th century at Vogue. Now can digital technology be the catalyst for its return? With the extensive use of computer-based visual arts software, the illustrator has found new ways to present, deliver and manipulate their work. Illustration has found a resurgence in other publications and periodicals from independent magazines to national newspapers. Has the mass consumption of endless digital photographic media started to create a need for a more human connection, the character, and the individuality of an analogue image?

Vogue’s golden years of illustration can be looked back upon, as a time when the interpretation of social culture and fashion was as important as the designs themselves. When illustrators influenced and interpreted art movements and delighted their audience with the anticipation of the next cover.