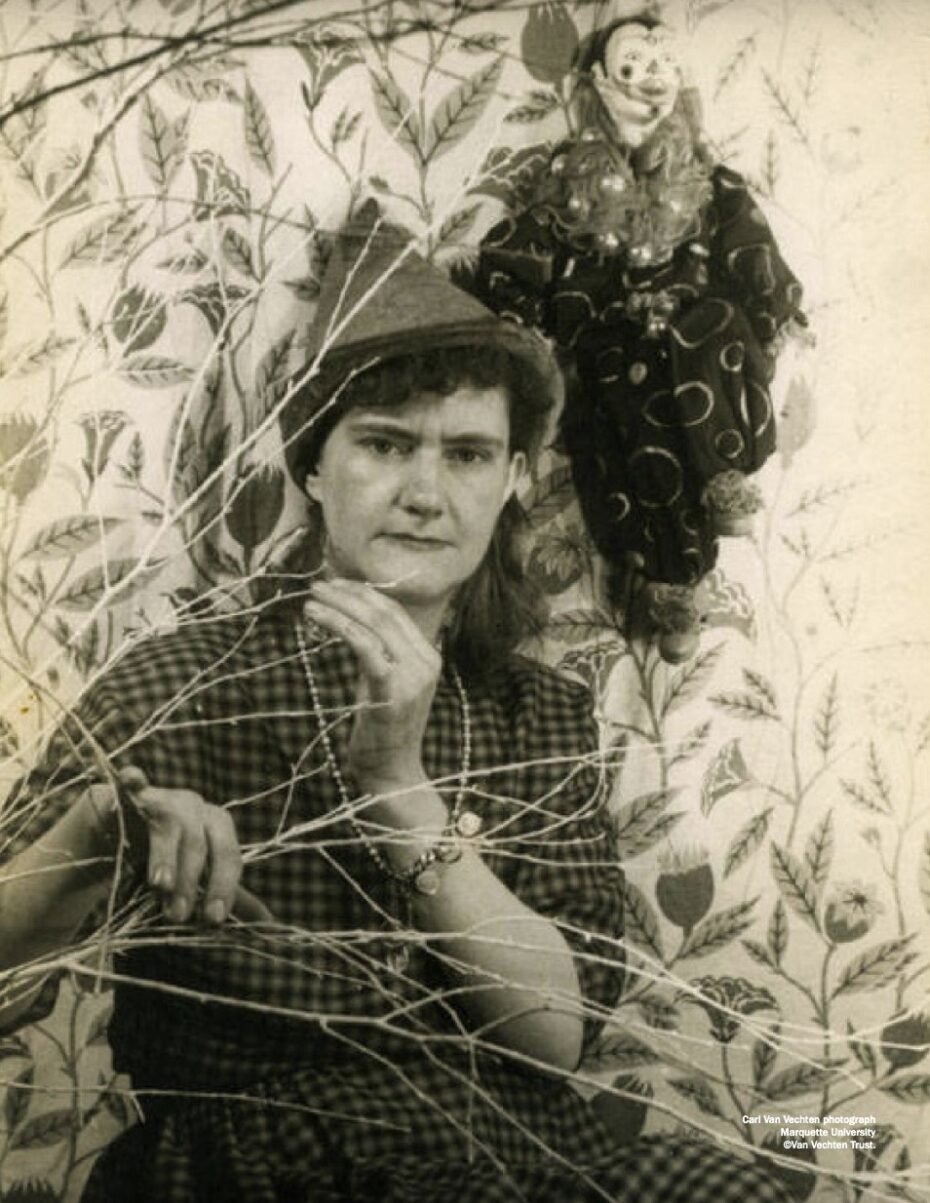

“I am a witch, oh that’s true”, confirmed Gertrude Abercrombie to a Chicago radio host in 1977, the year she died. In truth, the strangest thing about Gertrude Abercrombie is that she isn’t a household name among the Surrealist greats of the 20th century. Sure, she wore pointy hats, cast spells, lived in a spooky Victorian house on the south side of Chicago and kept black cats as companions, but the real magic is in her work. Haunting, otherworldly and eccentric but incredibly pleasing to the eye, her close friend Dizzie Gallespie once said “her paintings were jazz” – a world she also knew intimately. This fall, an auction of the “most significant selection of Gertrude Abercrombie paintings to ever come to market” will take place. So grab your broomstick, put on a jazz record and let’s step into the salon of Chicago’s “bohemian queen”.

For someone who ended her life as a recluse, Gertrude Abercrombie ran with quite a crowd. During the 1940s and 50s, she was at the very centre of avant-garde Chicago and hosted an artistic salon. Much like a more famous Parisian counterpart of the same name, she was often called “The Gertrude Stein of the Midwest.”

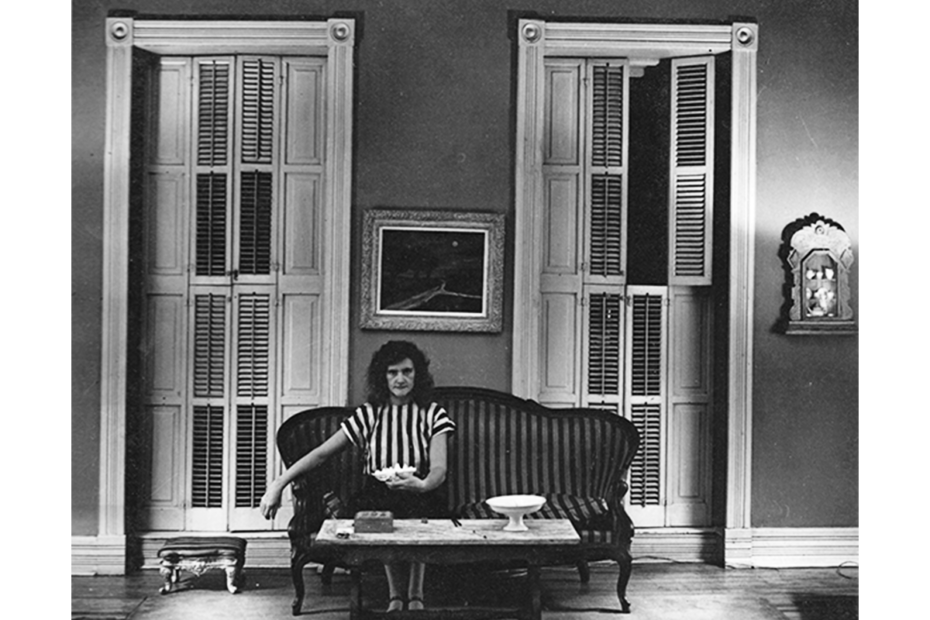

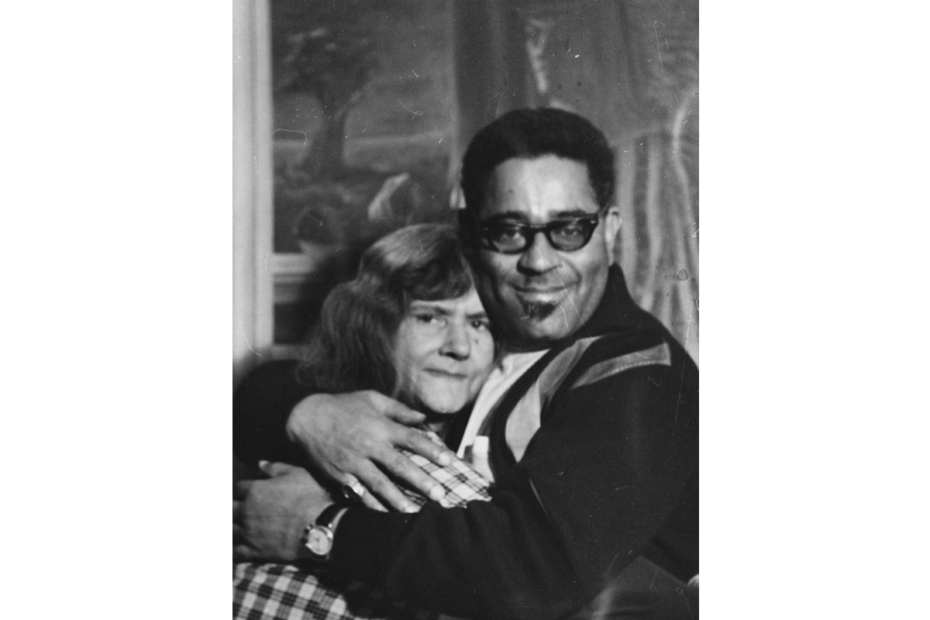

Her home, full of bohemian Victorian furniture, played host to major literary figures, critics and photographers, but it was most notably a haven to Black jazz musicians, serving as a welcoming refuge when they faced hostility touring in the Jim Crow era. A talented piano player herself, she was friends with music legends such as Sonny Rollins, Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Sarah Vaughan and counted Dizzy Gillespie as one of her closest friends, who led the band at her wedding.

Gertrude was born in Texas in 1909, grew up in Illinois and, for a short period, Berlin; an experience that gave her a lifelong love of foreign languages. Art came early and easily to her, at least partially due to the fact that both of her parents were opera singers – her mother a prima donna whose career took her as far as Europe before losing her voice to illness.

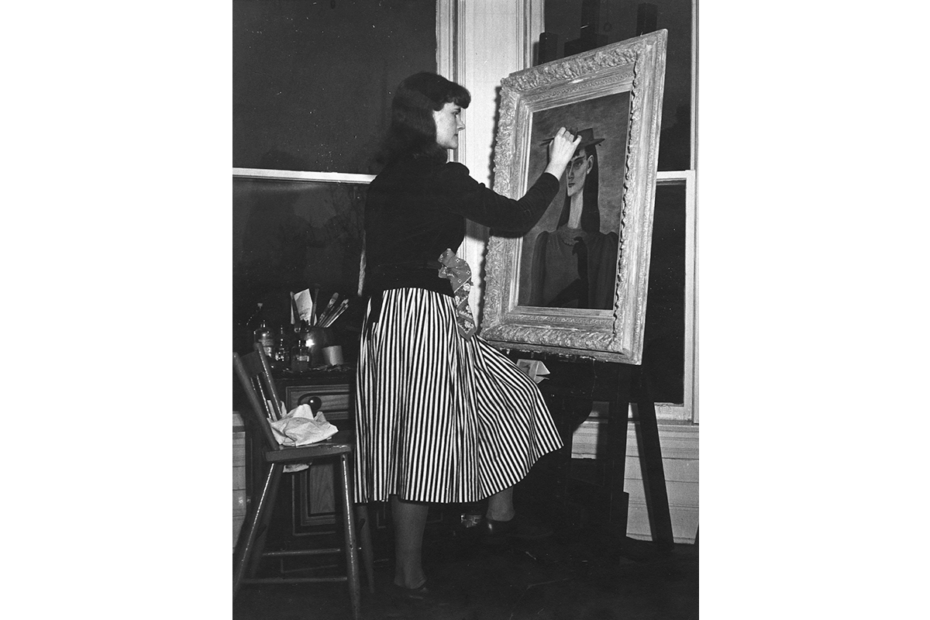

A woman of many passions, Gertrude studied a bit at the Art Institute of Chicago, and a bit at the American Academy of Art before getting her first job at a department store. When she realised painting was her vocation, she began an artistic career in earnest. Her style was eclectic and mysterious; well suited to Chicago, a city that championed surrealist art in the 1930s and is now known for its important collections.

Her début in the art world was at a fair in Chicago in 1932, where she sold her first painting and received considerable attention. She quickly became enveloped in the city’s arts scene, but while she was alive, Abercrombie was barely known outside the Chicago cultural circuit. She never settled into one artistic group, nor did she stay with one gallery, but constantly moved around, independent in her own style.

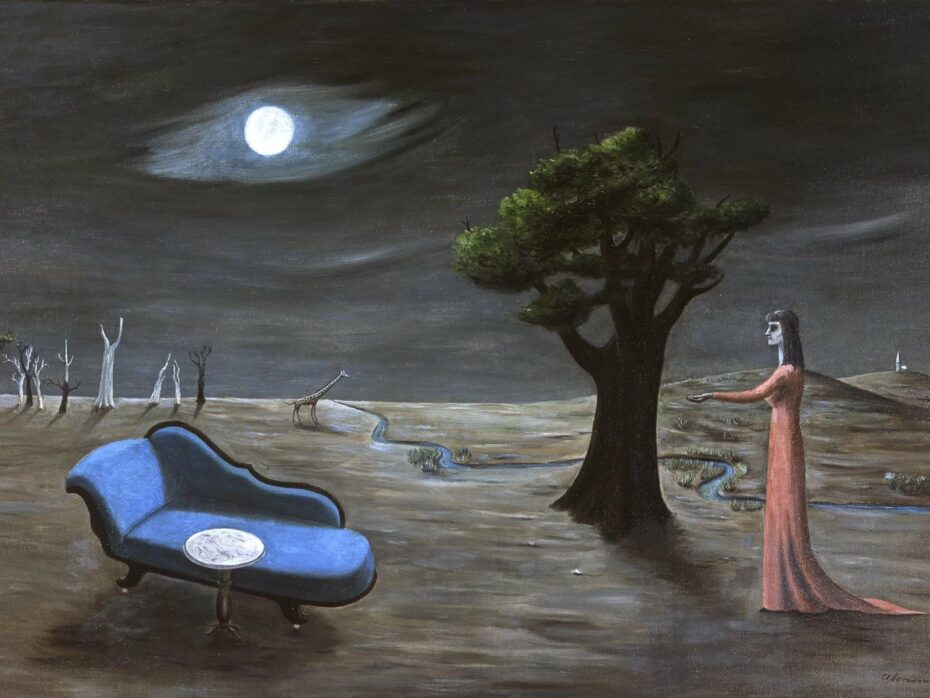

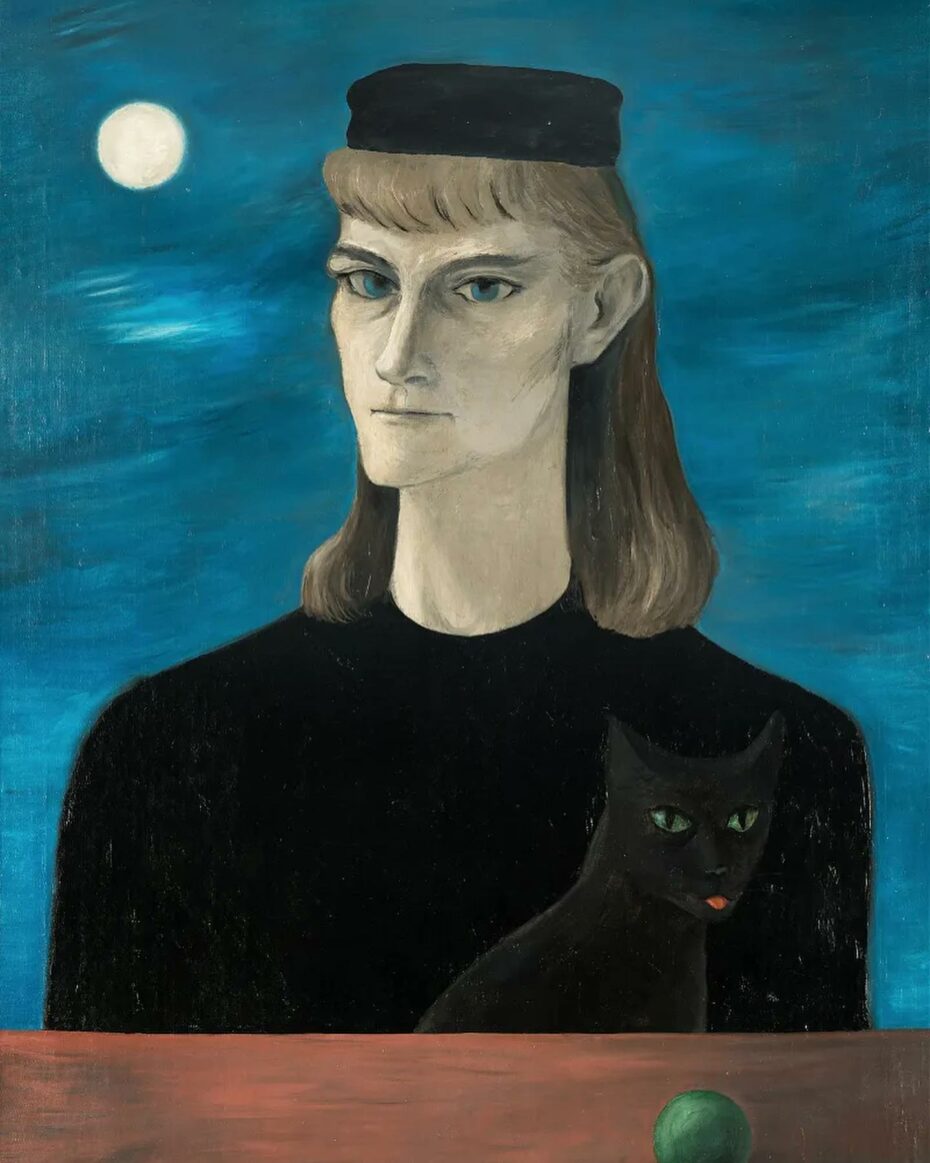

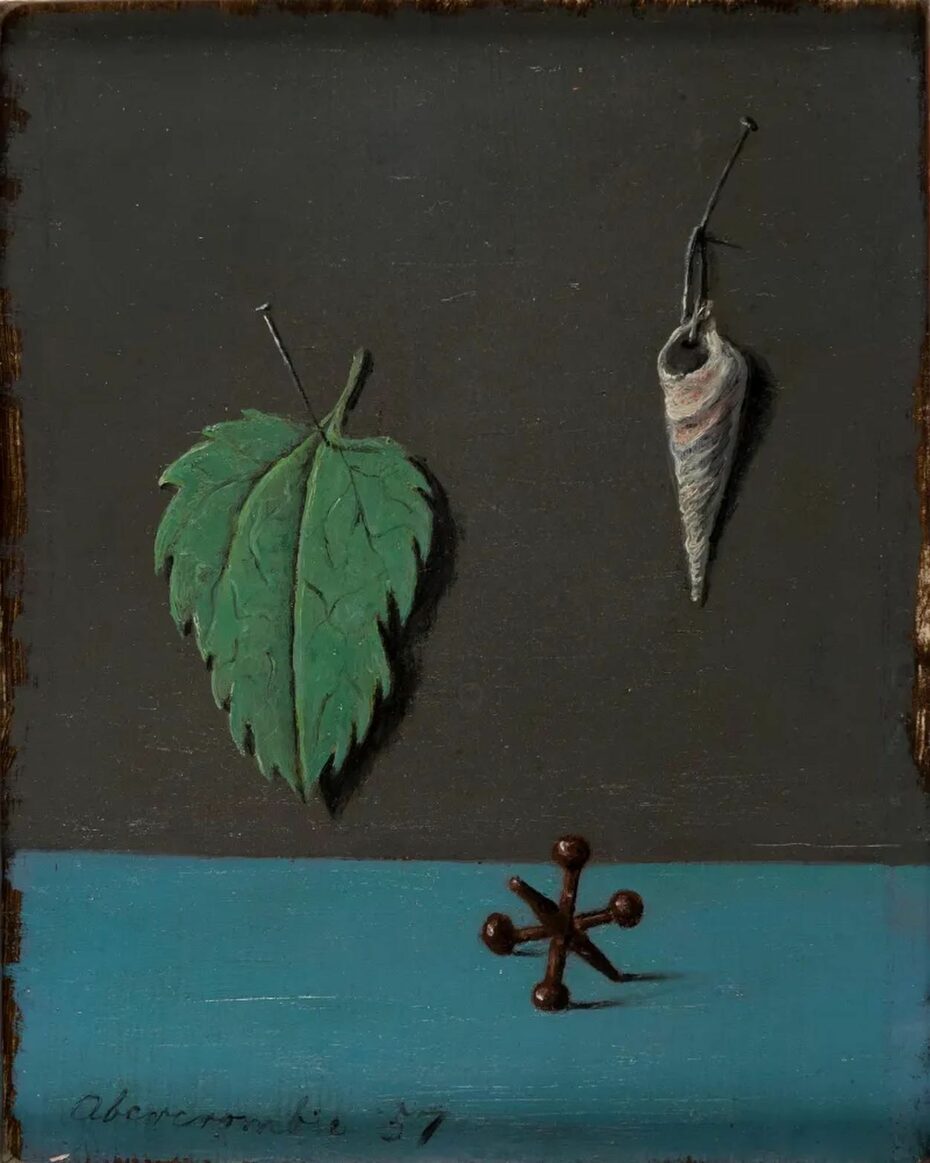

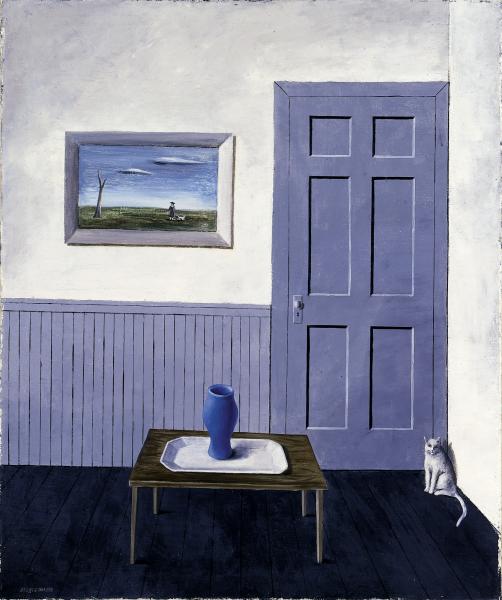

She often represented herself in her works, often posed alongside animals or objects. “It is always myself that I paint” she once said. Similarly, her paintings often delved into the philosophical and symbolic, if not the esoteric. The same symbols repeat across her work (cats, women in gowns, the night sky), and many of her paintings are set in the same dreamy, barren landscape.

Abercrombie’s subjects would come to her in dreams. She once described how important dreams were to her work:

Surrealism is meant for me because I am a pretty realistic person but don’t like all I see. So I dream that it is changed. Then I change it to the way I want it. It is almost always pretty real. Only mystery and fantasy have been added. All foolishness has been taken out. It becomes my own dream.

Abercrombie’s upbringing in the Midwest was an important part of her character and shaped her art. Her simplistic style and interest in quotidian subjects show the influence of regionalist painters.

The later years of Abercrombie’s life were troubled by health problems that decreased both her artistic and social output. She died in Chicago in 1977, having withdrawn from society, but not before giving the Midwest one more gift, the Gertrude Abercrombie Trust, which donated her works to museums across the region. Nevertheless, her work was overlooked for decades before a gallery in New York exhibited a retrospective of her paintings in 2018. At the time, you might have been able to pick up one of her pieces for just a few thousand dollars but Gertrude’s legacy is finally getting the attention it deserves.

In the world of art collecting, the auction house Hindman hosted an unprecedented sale of many of the artist’s best works last September : Casting Spells: The Gertrude Abercrombie Collection of Laura and Gary Maurer. Prices estimated at the lower range started at $10,000. Arguably a bargain for an artist who should soon be finding her long-overdue and rightful place in art history.