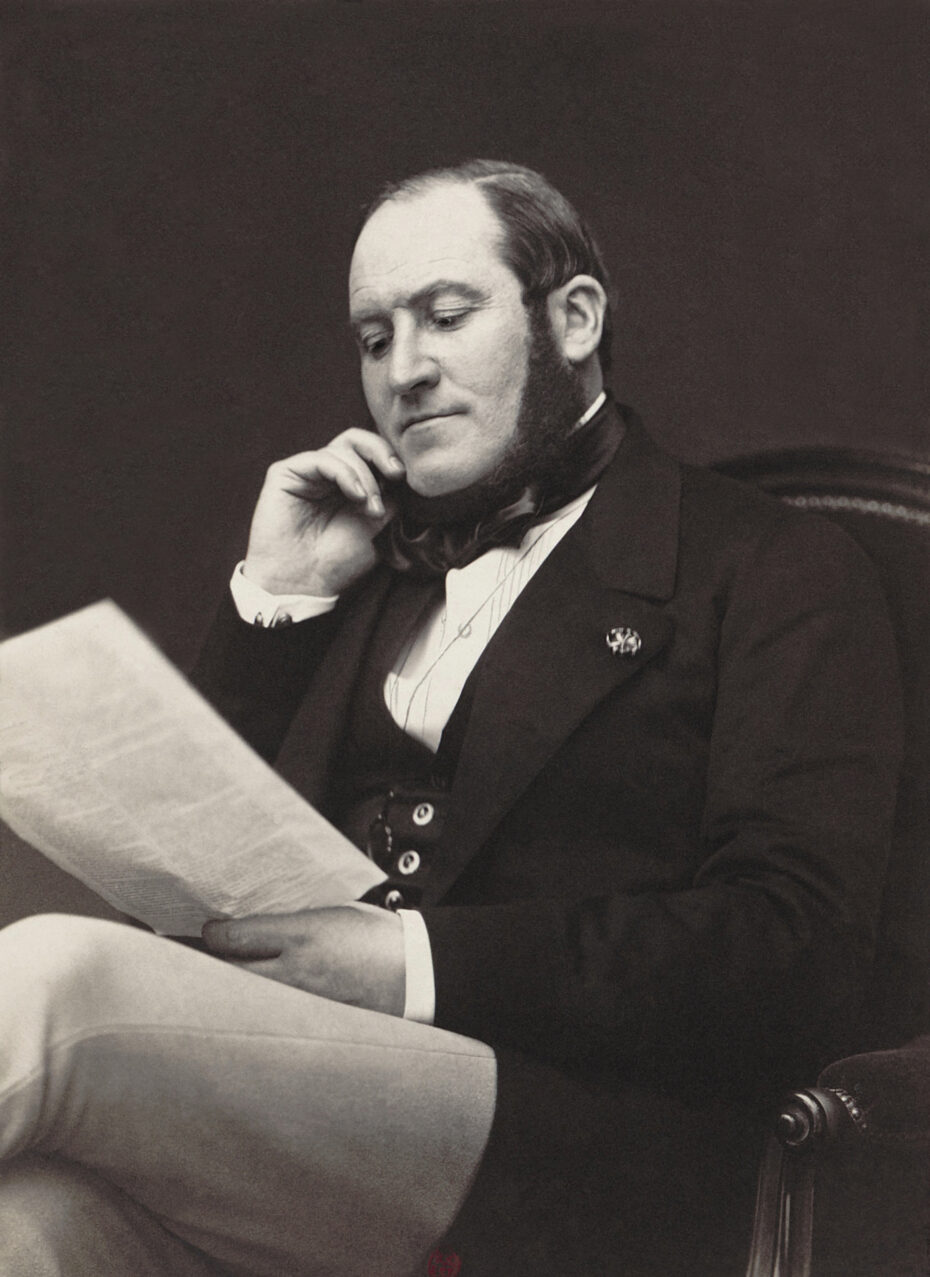

Walking through Paris, as a tourist or a local, it’s hard to miss the sense of harmony that the city exudes. The standardized buildings, the parks, the long angular streets that seem to always lead to a landmark. Everything feels intentional, organized, and connected. This isn’t by chance, this sensation is largely thanks to the work of a single man, Georges Eugène Haussmann, (AKA Baron Haussmann). Few cities have been so transformed by one individual as Paris was by Baron Haussmann. As prefect of the Seine (the old way of saying prefect of Paris), he was given the opportunity every urban planner dreams of, to completely redo a city. This was only possible because of the political context of the time; Haussmann was named prefect and given the project by the emperor Napoleon III. With absolute power came absolute aesthetic control, and Napoleon III and Haussmann took full advantage of it.

Inspired by the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire, Louis-Napoleon had begun several projects to expand and improve Paris. His plans had social, political, and aesthetic goals. Recent cholera epidemics had revealed the disastrous health effects of dense urban living and lack of access to clean air and water.

Rue du Jardinet, demolished by Haussmann to open boulevard Saint Germain photographed by Charles Marville

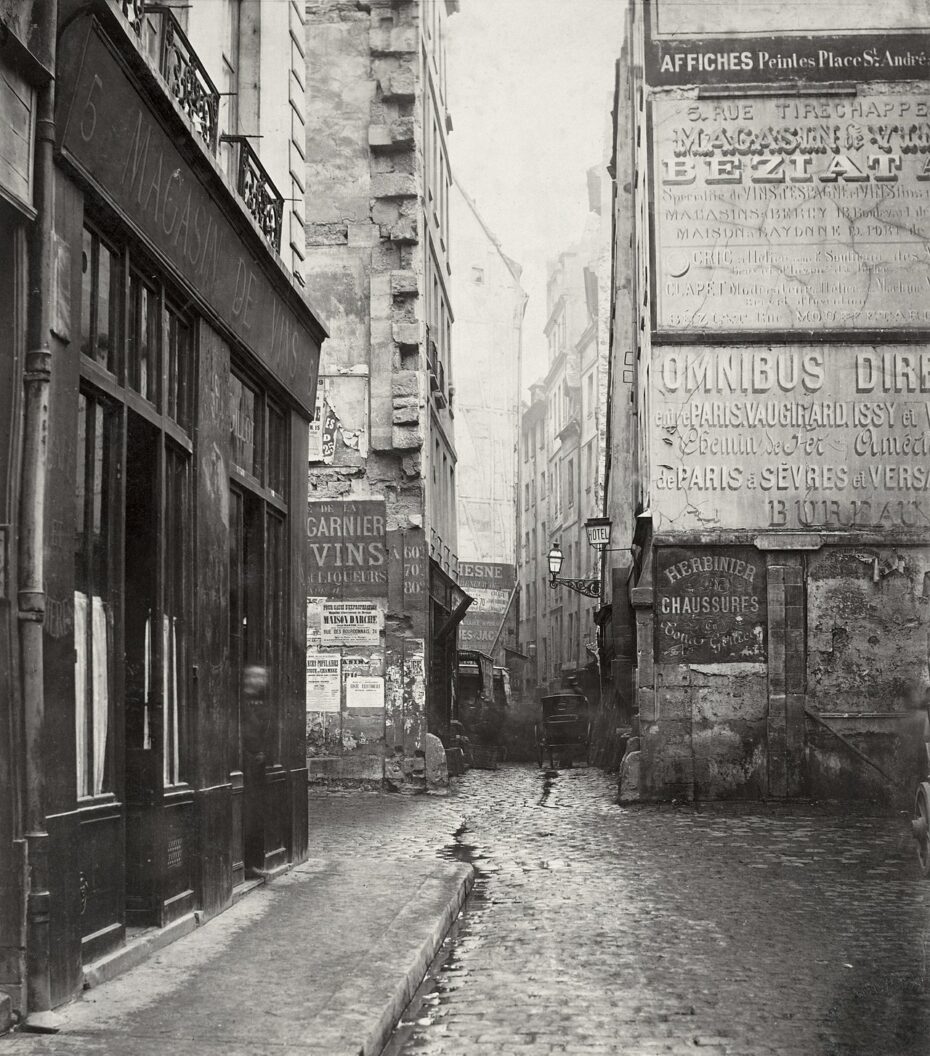

Rue Tirechamp, demolished to create rue de Rivoli photographed by Charles Marville

As president Louis-Napoleon oversaw the creation of subsidised housing and began to build the Bois de Boulogne Park, but his prefect of the Seine, Jean-Jacques Berger, did not work fast enough and lacked the passion Louis-Napoleon held for the project. So when he went from President to Emperor (after leading a coup-d’état to extend his power), Napoleon III hired Haussmann, sensing a kindred spirit in his enthusiastic and persistent nature. A born and raised Parisian, Haussmann rose through the ranks of political society as a lawyer and civil servant at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1853 he was made prefect of the Seine and directly given the task to make Paris bigger, cleaner, and more beautiful. He jumped into action and began building new boulevards that would connect and unify the city.

In the mid 1800s, Paris essentially became one big construction site.

View of Boulevard Henri IV from place de la Bastille, 1876 photographed by Charles Marville

Whereas before, when the river Seine was the centre of commerce, Haussmann’s large boulevards would become the new highways of Paris. On the right bank, these included Boulevard Strasbourg, Boulevard Sébastopol, and the completion of the Rue de Rivoli. Together the new streets formed a large cross, which gave the project its name, la grande croisée de Paris. Haussmann insisted on the streets being straight and broad. This was to give the public access to optimal light and air, or to prevent the building of barricades, depending on your political persuasion. Squares or important buildings like town halls or theatres were placed where major roads met.

Napoleon III wanted the first improvements done in time for the 1855 Paris Universal Exposition, so Haussmann dispatched teams working all day and night. A prefect of the Seine had never had so much power, for each decision, Haussmann simply had to ask the emperor for permission, instead of the French government.

Haussmann and Napoleon III’s first program was focused on central Paris, which had been the epicenter of overpopulation, as well as the cite of much of the political upheaval of the previous decades. This reshaping of Paris had clear political symbolism. Napoleon III and Haussmann were trying to scrub the city of its recent tumultuous history, leaving only a clean, open future.

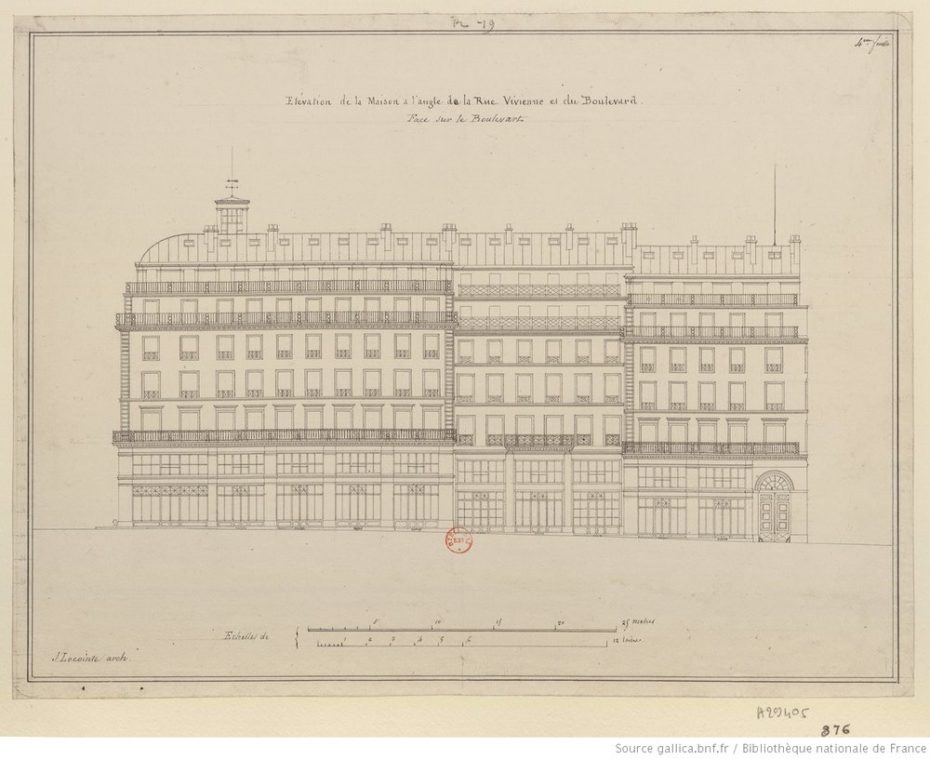

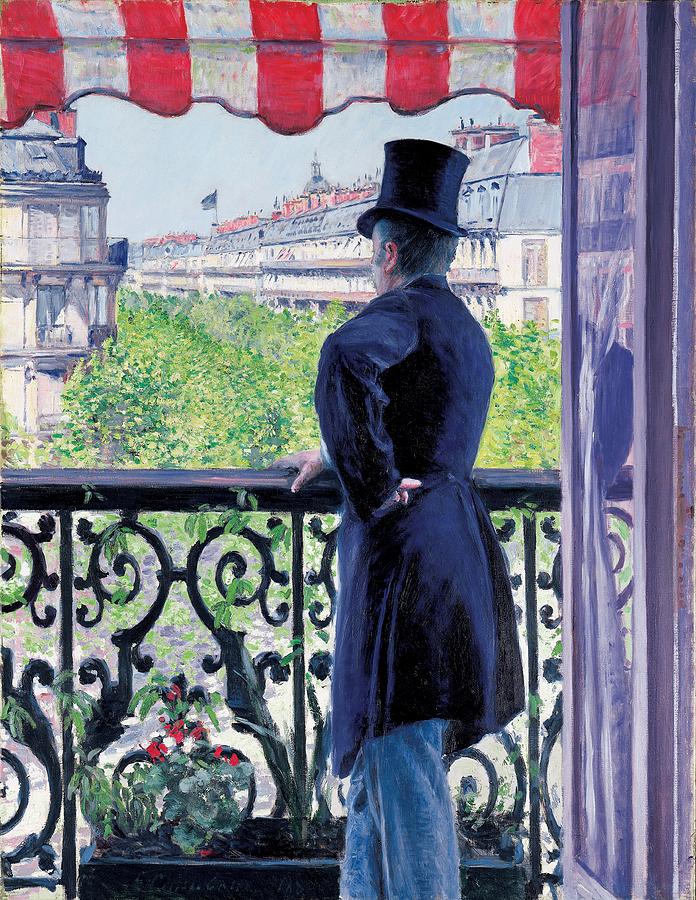

So what does the typical “haussmannian building” look like? After the Rue de Rivoli was finished, it became the model for the rest of his projects. The criteria included the number of floors; six at the max. The second and fifth floors were typically the ones with balconies – the most decorated ironwork reserved for the second floor where you could admire it best from the ground without the obstruction of a ground floor shop’s marquise. Second floor apartments were generally considered the “piano nobile”, reserved for the wealthy, with the roomiest living quarters and the grandest interior details. You’ll still find the fireplaces and ceiling mouldings are usually the most elaborate on the second floor. The top floor was usually inhabited by the lower-income tenant and the mansard roof’s angle were strictly regulated at 45 °. The material for the façade was of course, Lutetian limestone, also known as “Paris stone”, was mined from the quarries below. When streets converge at acute angles, the corners of the buildings’ angles were cut off or rounded or even concaved, or more specifically in architectural lingo, “chamfered”, to cleverly allow the eye to travel further around a corner.

After completing his first major project, the grande croisée, Haussmann began creating what he is perhaps most well-known for today: the boulevards. Enormous new streets were built on both banks, including the boulevard Magenta, Avenue Daumesnil, and boulevard Malesherbes on the right bank and avenue Bosquet, avenue Rapp, and rue Monge on the left. Several parks were also redesigned including the parc Monceau and the Jardin du Luxembourg. The entirety of Ile de la Cité was transformed to create new municipal buildings. The Etoile, the square that surrounds the Arc de Triomphe, was redesigned. Les Halles, Paris’ larges market, was transformed with large glass and iron pavilions. And he didn’t forget the little details – with his city architect Gabriel Davioud, Haussmann introduced official designs for everything from Paris’ famous hexagonal advertising columns to the public toilets and garden fences. These are the little details of course that helped make Paris look like Paris.

The renovations were to improve the lives of Parisians, but they were not without political motivations as well. The beauty of the new Paris was a demonstration of the power of Napoleon III and the French state. Under the emperor, Paris became a showcase of modernity, the model of a more accessible city. Yet, not accessible for everyone…

Haussmann and Napoleon III’s projects were often only oriented to serving the rich and many led to the displacement of poorer people to Paris’ suburbs. Their transformation of Paris, while appreciated by many, was also seen as a “bourgois-ification” of the city. Rents went up and many were forced to leave and live in squalid apartments on the outskirts of town, an ironic rebuttal to Haussmann and Louis-Napoleon’s supposed public health ambitions.

Haussmann was working below the streets as well. Anyone who’s read Les Misérable is already familiar with the sewers of Paris. Haussmann was as obsessed with the maze as Victor Hugo, but sought to improve it. The system of pipes was completely redone, allowing new water, gas, and sewage lines to be created.

Ever wonder why Paris has 20 arrondissements? Before Haussmann there were only 12. Much to the annoyance of their residents, who didn’t want to pay Paris taxes, Napoleon III and Haussmann annexed a ring of Paris’ suburbs, including Montmartre, Grenelle, and Belleville. This enormous increase of both Paris’ land and population size was a shock to the French people, but under an emperor, there were few ways to object.

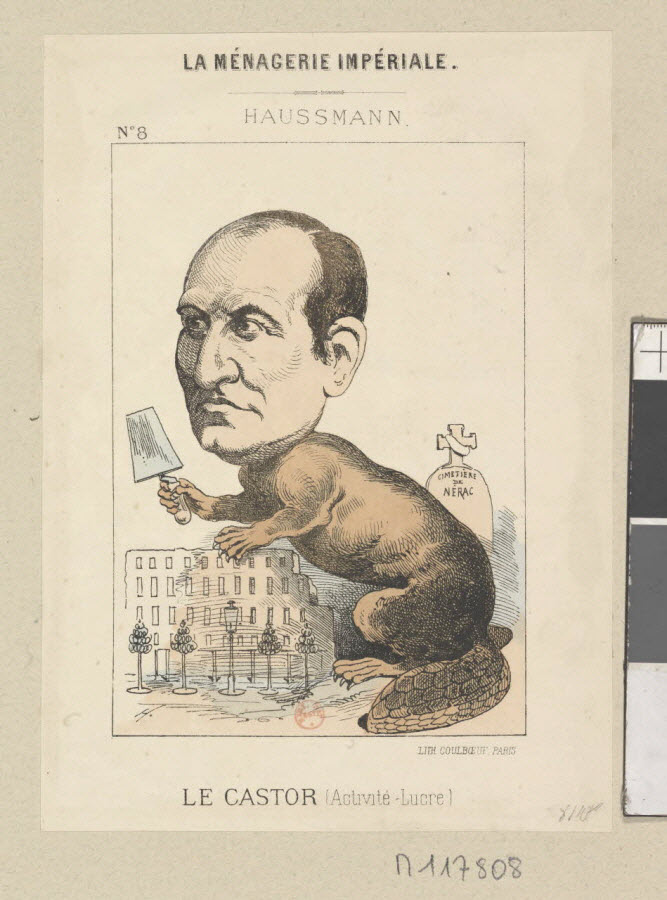

While his work was largely appreciated by Parisians, concern was mounting for the cost of this many projects, and he was not without his critics. Academics and politicians objected to him for aesthetic reasons, accusinh the project of rendering the city without character or history. It’s true that Haussmann’s passion for order sometimes got the best of him, like the famous story of him destroying several historic homes while creating the boulevard Saint-Germain because of his obsession for straight lines. In newspapers, he was caricatured as a beaver slicing up the city.

Haussmann’s architectural reign ended when Napoleon III’s political rule did. In 1870, the emperor was captured during the Franco-Prussian war and (yet again) the French overthrew their leader. The Third Republic began. Though Haussmann lost his job, the next prefect of the Seine finished many of his projects.

Haussmann achieved something that will never again be achievable without a totalitarian government. While his reputation remains complicated, Haussmann undeniably created the Paris we know and love today. With the support of Napoleon III, he brought to life a vision of what a city could be, a city that valued leisure time, green space, architectural beauty, and public health.

Paris is for the most part, a grand and elegant city thanks to Haussmann, but there are some parts of the old city that still remain almost unchanged, with clues to the “lost Paris”. And if you haven’t noticed already, we love following those clues.