The many style subcultures of post-war and modern Japan are rooted in rejection; a succession of generations refusing to traditional parental values. Each one has formed its own unique uniform of rebellion, but some have taken it to further extremes than others, riding dangerously on the fringes of society…

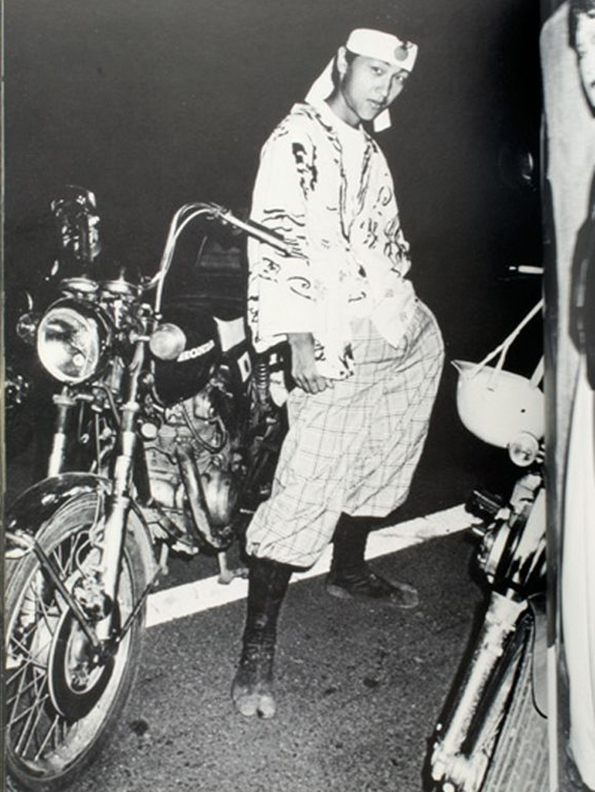

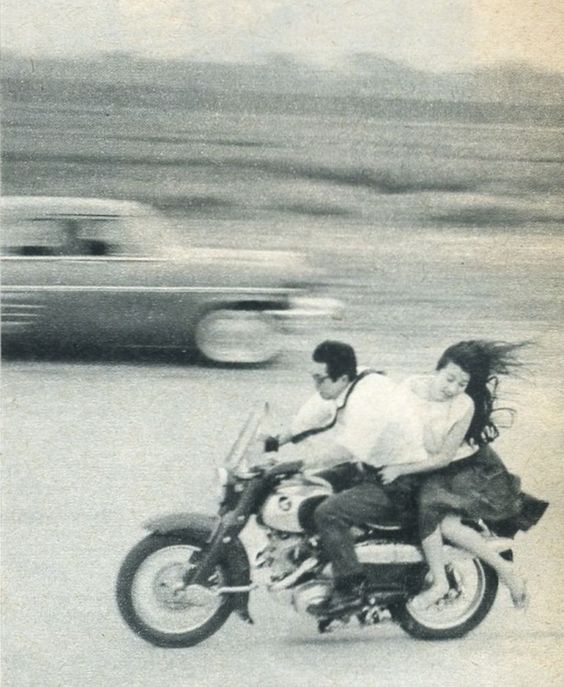

Anarchic, angry and restless, Japanese rebel bike culture emerged from the ranks of disaffected Japanese youth following WWII; a tribe of anarchic lost male souls, it was initially a male subculture, which refused to accept female members and was inevitably seen by the government as anti-establishment, anarchic and down-right criminal. Whilst some early members of the bike culture were rumoured to have been ‘failed’ Kamikaze pilots, their hardy and basic biker uniform, often inspired by the military jumpsuits and combat uniforms, was known most appropriately as tokkō-fuku or ‘special attack’ clothing.

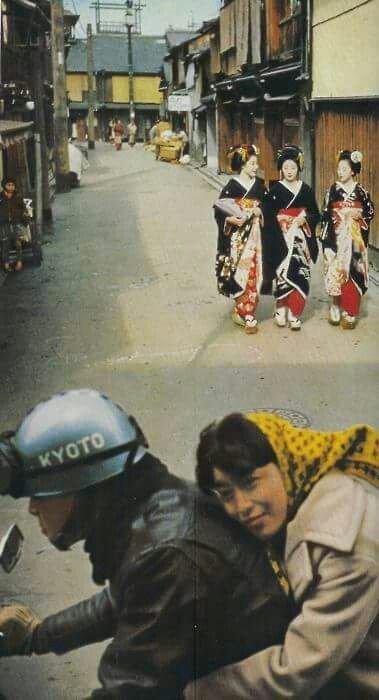

Growing increasingly aggressive, by the early 1970s, they came to be known as the bosozoku, which roughly translates to ‘a runaway train’ or ‘out of control vehicle’, seeking thrills in crime, speed and dress. It was imperative that the integrity of their bikes was maintained but modified illegally for rapid manoeuvre and quick get-away from their petty crime scenes.

Initially, women had no part in the ‘real action’ of the bosozoku other than to ride as decorative passengers for the most part. But the 1960s saw the rise of political freedoms and feminism. The girls who had perched on the seats of the Bosozoku boys now wanted their own gangs, and with various social changes and youth movements taking hold, Sukeban culture emerged.

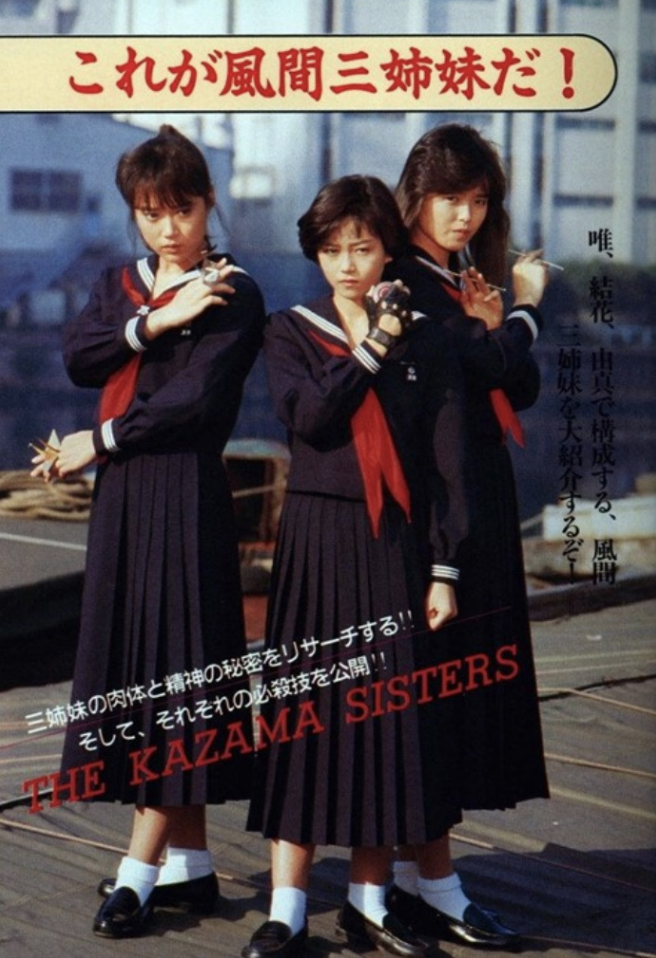

Sukeban is a Japanese word referring to delinquent girl gangs or the leader of the gang. The gangs had their origins in disruptive petty criminal student groups in schools and colleges – those who smuggled cigarettes and alcohol onto the school premises. The girl gangs ranged in both size and unashamed titles such as the ‘Tokyo’s United Shoplifters Group’ of around 80 girls and the ‘Kanto Women’s Delinquent Alliance’, reported to have had 20,000 members. The reputation of these criminal girl gangs’ exploits was so infamous that during the 1980s, the Japanese police titled their ID culprit-tracing sketches of the girls and their kit as “omens of downfall”.

Sukeban girls sported a very distinctive look. Japanese sailor-style and western-influenced school uniforms were modified and exaggerated. Skirts were actually lengthened, possibly in rejection of the sexualised school girl miniskirt, while their tops were emblazoned with gang motif embroidery. Under their skirts, they hid an array of light weaponry from razor blades to bamboo swords and barb-wired baseball bats. Life for the girls on the inside of Sukeban society was often pretty rough. Gangs had strict rules, hierarchies and punishment rituals. Disrespecting a senior member or stealing a boyfriend, sometimes considered a petty crime; punishable by cigarette burns for instance.

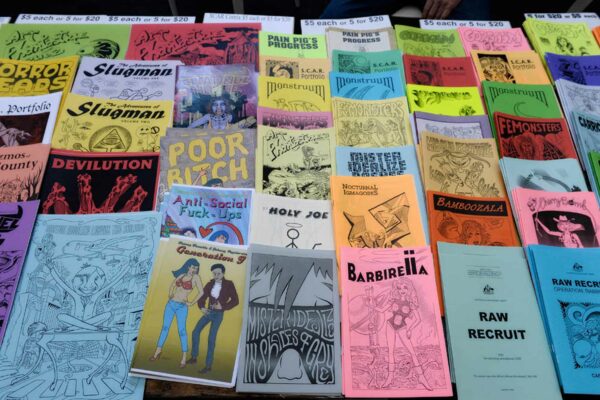

This edgy and dangerous lifestyle in contrast to the rigorous conservative Japanese traditions of old soon caught the attention and imagination of the Japanese media. Their attitude and dress culture would influence fashion over the next decades and the underworld subculture would migrate into film, TV and mainstream Japanese culture, as well as the seedier realm of Japanese erotica, fuelling fantasies further. The appearance, not the necessarily the behaviour, of the Sukeban became a model for popular characters in young adult Japanese comics too. Today, the Japanese media anime and manga tales are awash with exaggerated doe-eyed, super sexy rebel schoolgirls and spiky-haired, weapon-wielding heroes in trench coats exploding from comic book pages and cartoons.

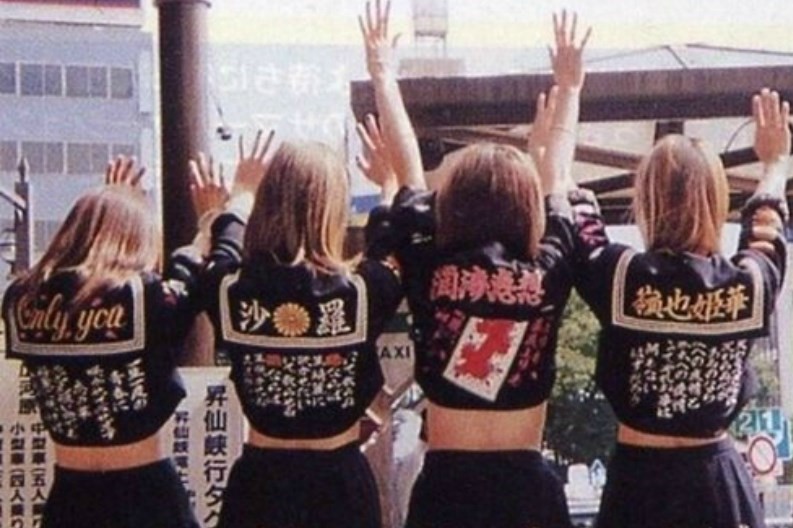

The 1980s saw Sukeban’s unmistakable look fade out for a period as the traditional school uniforms were abandoned for even more extreme styles. With the punk movement making waves in the West, pockets of Japan’s rebellious female youth also morphed in a new direction as girls on loudly-coloured and loudly-tuned bikes began burning rubber under the same modus operandi in anarchy as their male counterparts, the bosozoku. The male motorcycle gangs, commonly associated with the yakuza, had already started to decline by then with strict government crackdowns, but out from under their shadow, a female faction took to the streets – this time, emerging on their own two wheels.

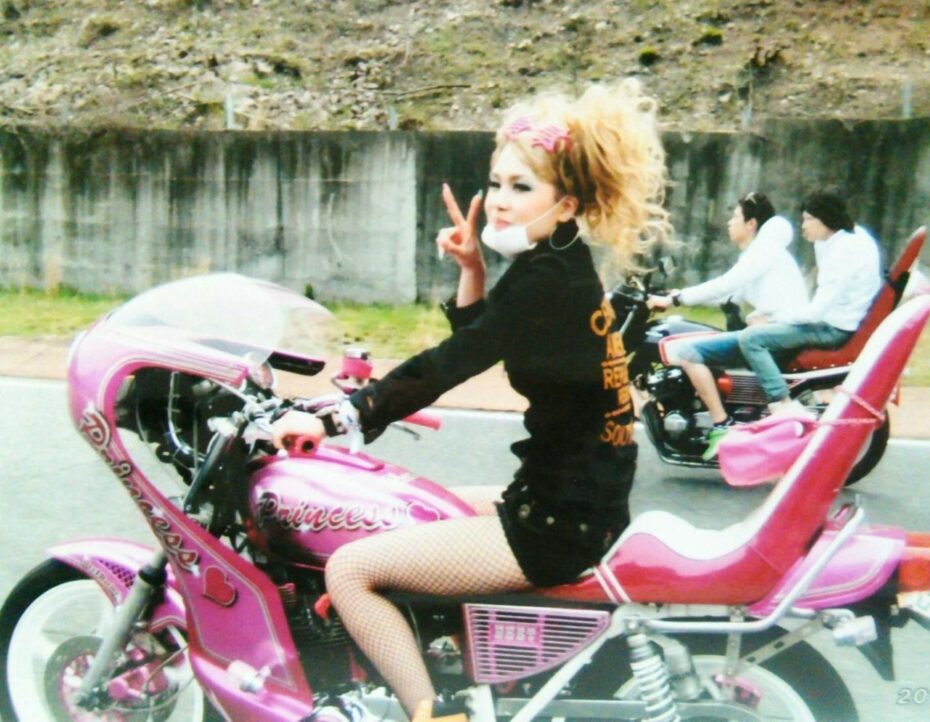

Immediately identifiable, their hair was brightly dyed or boldly permed; eyebrows were plucked impossibly thin with almost no make-up except exaggerated dark eyeliner. Their fingernails were exotically and randomly coloured and decorated with an assortment of tints and weapon-like spike and stud accessories. The multiple piercings to their ears, nose and bellybuttons were essential embellishments and ‘trademarks’.

The girls also pirated the boys’ tokkō-fuku overall jumpsuits, now bright and colourful, plastered with their symbols of allegiance and provocatively worn open to display their bandaged chests. Their clothing, like their bikes, was adorned with garish gang insignia, symbols and slogans. Flashy, outrageously colourful girly-pink graphics and lashings of extra buttons and badges were the final touches to this unmistakeable grungy tough-cookie identity.

Over the years, bosozoku girls have made their own very distinctive, increasingly extreme modifications to their bikes. The standard modern Yamaha, Honda and Suzuki Japanese machines are used instead of the old style western bikes. The Japanese bikes are decorated then ‘chopped’: the front fairings reworked into assertive and sculptural prows and adorned with a garnish of glittering girly graphics. The fuel tanks are equally enriched, plastered in sparking rainbow colours with motifs of Kamikaze pilots’ rising sun icons or gang icons. The entire bike, like their clothes, are typically covered with graphics, stickers and badges and inevitably very, very pink.

Technical modifications are limited to the installation of higher narrow handlebars to aide ease of escape through the tight traffic and the exhausts modified to be irritatingly noisy and attention-seeking. The pièce-de-resistance on their bikes is the seat, a snaking sculptural luxurious chaise-longue for two; super comfortably upholstered high-backed thrones for the pillion passenger and sometimes even a back for the pilot. The whole bike is then topped off with a glowing array of neon lights and fluttering gang flags as they concealed their identity behind surgical face masks.

Some women do take it to extremes, acting as daringly and recklessly as their male bosozuko counterparts, jumping red lights and smashing the occasional grumbling motorists’ windows with baseball bats, while others, particularly with the rise of social media, are simply in it for the fashion and their passion for fast, shiny wheels.

What remains of the gutsy Bosozoku girl gangs today is often a cryptic clash of styles from both the earlier Sukeban subculture and the grittier punk look that emerged in the 80s. Riding into the future, if Kim Kardashian trying to make the motorbike trend happen gives us any indication – perhaps it’s only a matter of time before one of the big brand fashion houses chooses the bosozoku girl as their next muse. Is it just us or is this screaming Gen Z fashion?