One of the most exciting technological advances of recent decades is arguably the 3D printer, allowing creators to turn their wildest inventions into real-life products. But 3D printers are far from the first foray into producing realistic, 3-dimensional replicas. Photosculpture is a process dating back to the 19th century, using a series of photos taken in the round to make a sculpture.

Photosculpture was invented by French painter, photographer and sculptor François Willème, who studied at the famed Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris and made models for art bronze manufacturers. He was interested in making a “sculpture exactly similar to the model (living or inanimate)” according to an 1861 article in Moniteur de la photographie. In fact, another sculptor, Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon, had also been interested in using the budding field of photography for his sculptures, but gave up this dream and became one of the most renowned French photographers of his era instead. Little more is known about Willème though, and the only representation that remains of him is, as you would guess, a photo sculpture. But his legacy has been cemented through his ingenious invention.

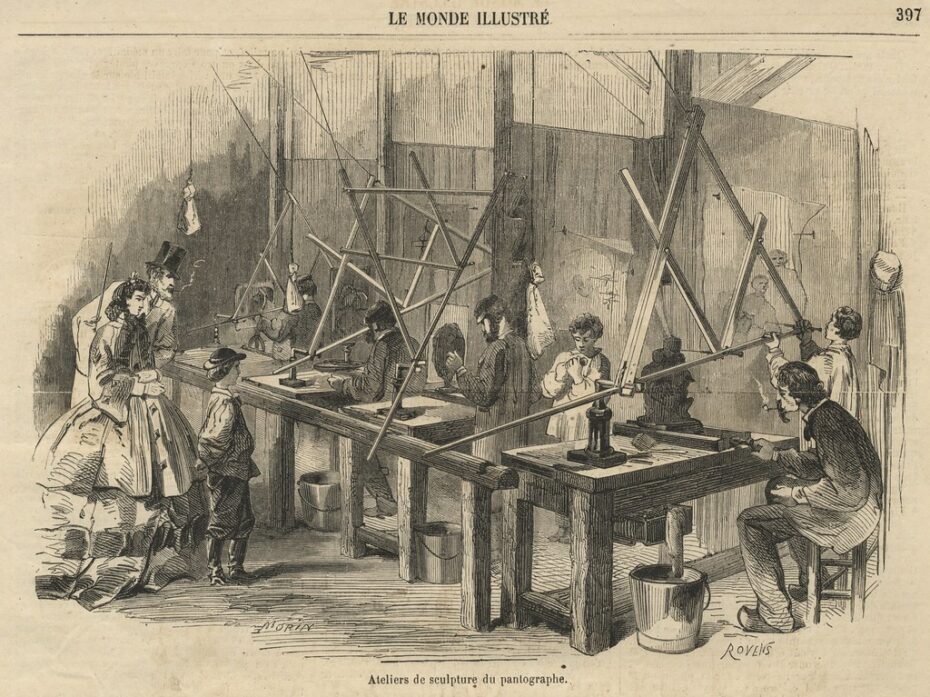

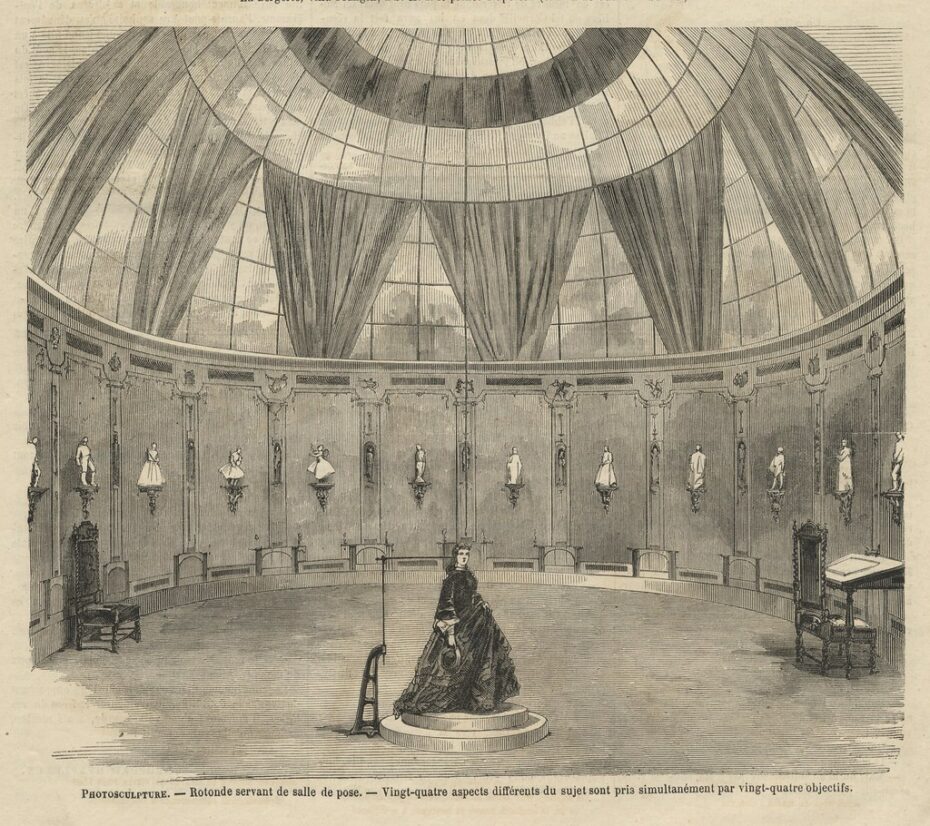

Photosculpting was an intensive process relying on 24 cameras, one every 15 degrees. Willème would synchronize the 24 photos to make the 3D image, projected onto a screen. A pantograph (a mechanical device for tracing an image) was used, with the different photo layers cut into sheets of wood.

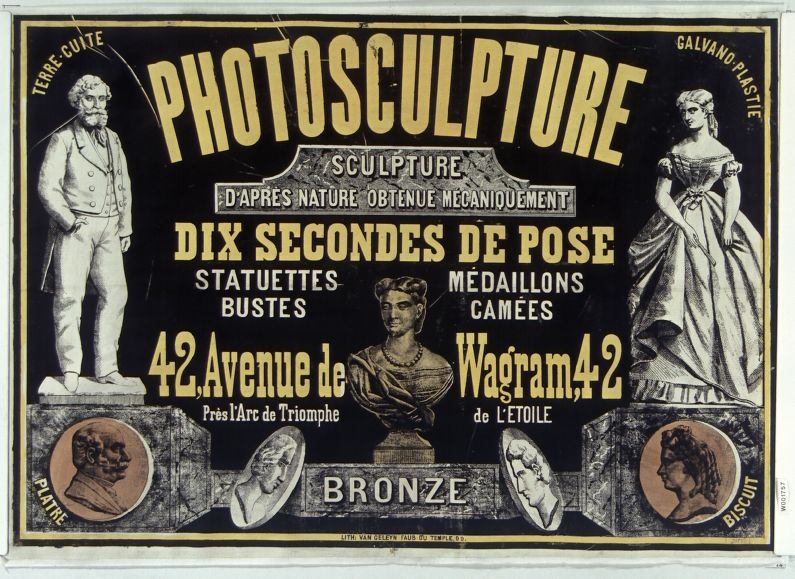

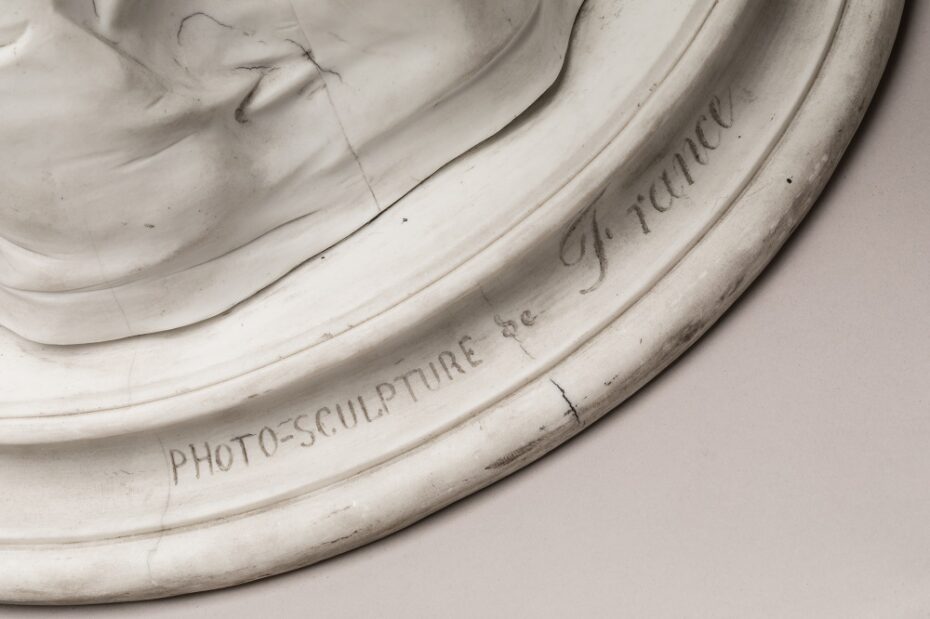

The pieces of wood were put together to make a rough 3D replica of the original object that he would fill in with clay and then cast or paint using a variety of materials including bronze, plaster of Paris and terra cotta. The pantograph allowed him to make sculptures in a variety of sizes, including a 50-centimeter statue, a medallion or a bust.

To help visualise the process, here’s a 1939 film by Pathé explaining the process:

Willème filed patents in France (as well as the United States and the United Kingdom). The American patent reads, “By this improved process I am enabled to produce sculpture exactly similar to the model, whether living or otherwise, with much greater rapidity, at a less cost, and by the aid of persons having no previous knowledge of the art. I may further lessen the time necessary for the sitting and produce sculpture of larger or smaller dimensions than the original, or in any other proportions desired.”

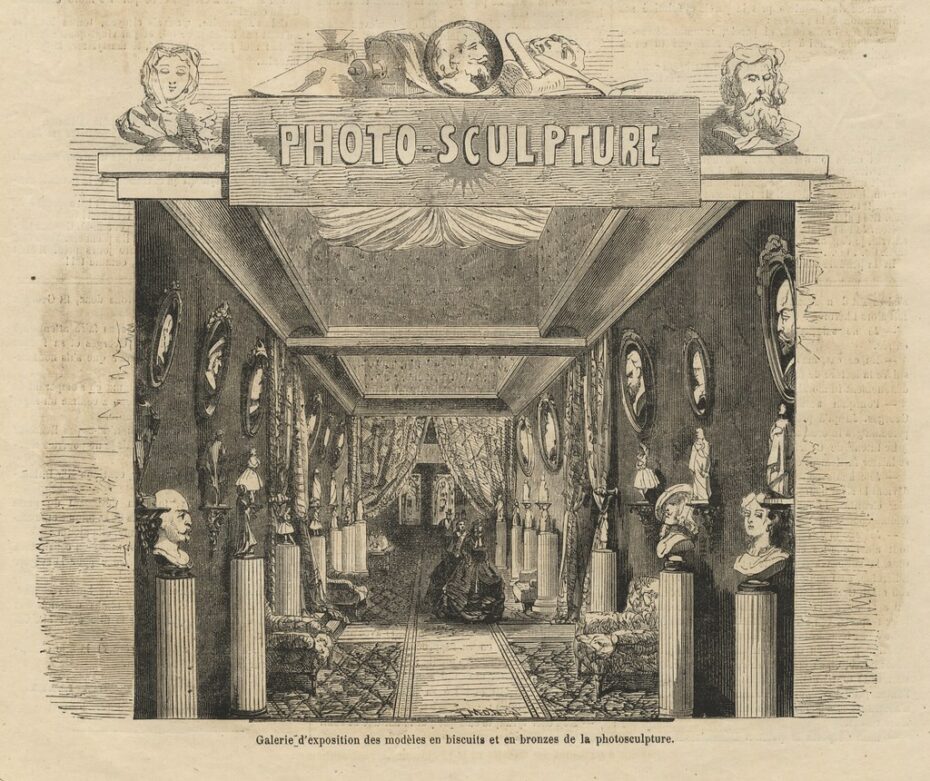

Compared to traditional sculptures, these were a quick and affordable art form. Photosculptures took only a few days to make (compared to months for a conventional design) and cost a few hundred Francs (compared to thousands for larger versions). Willème presented the process at the Société française de photographie in 1861, garnering great attention and a slew of high-class clients of the Second French Empire, from members of the imperial family to those in creative and literary circles.

These included Ferdinand de Lesseps (best known for building the Panama Canal and for one of his descendants marrying a Real Housewife of New York), the novelist Théophile Gautier and actress Augustine Brohan. The popularity of photosculptures expanded beyond France, with studios opening in London and New York. Willème was even awarded the insignia of the order of Charles III of Spain after going to Spain to create portraits of the royal family.

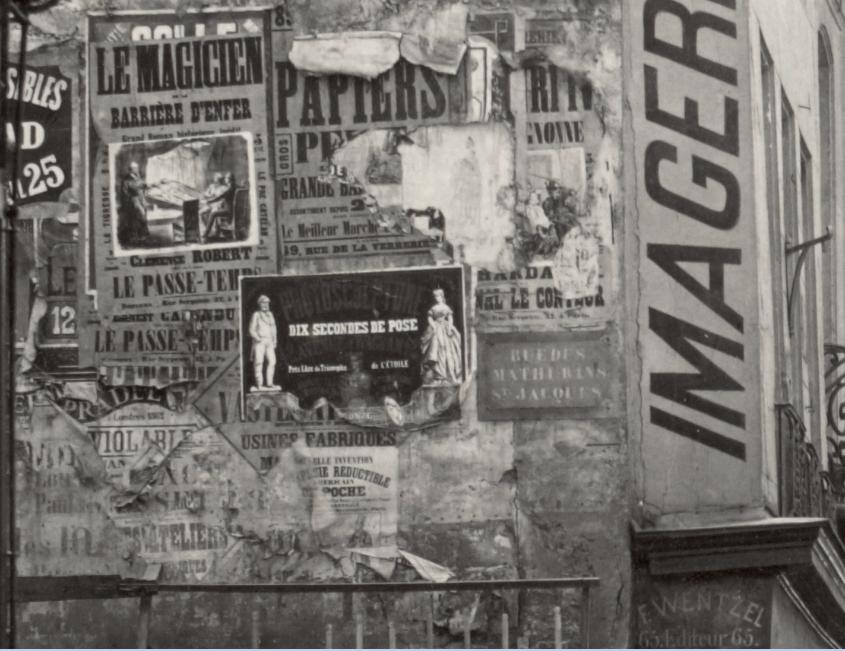

He opened a big Paris studio near the Arc de Triomphe from the funding he received; among his investors was Isaac Péreire (a banker and grandson of the man who invented the Pereire calculating machine). The impressive space featured a cupola (a rounded dome ceiling) with panes of blue and white glass. But by the time he showed off his design at the 1867 Universal Exhibition, the photosculpture trend was already waning. The studio closed and Willème left his own company in 1869, although the business continued without him. He returned to his hometown, where he gave drawing lessons at Turenne College.

One of the reasons photosculpting didn’t explode in popularity was perhaps because of how complicated it actually was. In a 1899 edition of La Science française, Louis-Philippe Clerc, who often wrote about photography, described it as the earliest attempt of using photographic methods to obtain a sculptural relief image of a living model. He also mentioned a different, simpler technique called photostery created by the photographer Lernaic and developed by Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, known as Nadar, who famously took the first aerial photographs. But photostery was not a standalone sculpture, but simply a form of photoengraving, giving an existing photo a 3D effect through a relief image. Italian engineer Carlo Baese di Castelvecchio (a relative of Napoleon Bonaparte) also patented an interesting method of object reproduction using photosensitive gelatin whose size would change depending on light exposure.

If you’re looking to see some historic photosculptures, many are housed at the Musée Carnavalet in Paris, including models of stage actors Denis-Stanislas Montalant, known as Tibot, and Céleste-Rose Beauregard, known as Rose Deschamps. There’s also some at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, the world’s oldest museum dedicated to photography. And if you want to see exactly how a photosculpture worked, in 2012, students at the Winchester School of Art recreated the apparatus…