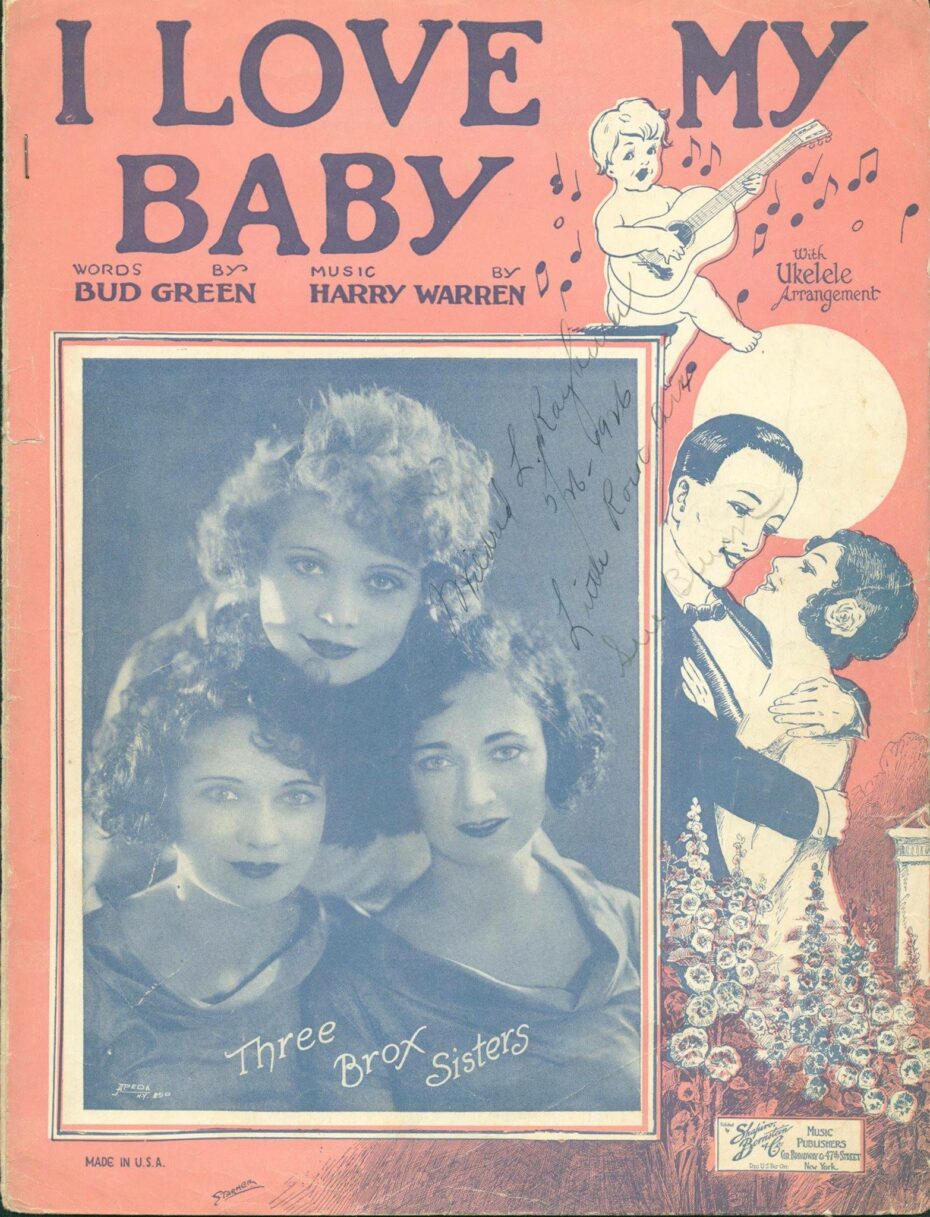

Before the Spice Girs, before Destiny’s Child and TLC, even before the Supremes, there was a litany of female singing groups – often found in threes, often known for their harmonic prowess, and often found on the great vaudeville stages of the time. They laid the foundation for the girl group as we know it today. And it all starts with a group known as the Brox Sisters.

Wait, who? Information on the Brock Sisters – as read their birth certificates, the family name “Brock” was later changed to “Brox” for theater marquees – is slim, and fickle. Some claim they were born in Kentucky and Tennessee, and raised in Alberta, Canada. Others say it was the other way round. One account throws Iowa in as a contender. The Brock Sisters, then, came into this world in the first decade of the twentieth century as one ticks off years on their fingers – Eunice in ’01, Josephine in ’02, and Kathleen in ’04. As is the case with many performers, they would later forgo their birth names on the stage and don something new instead. Ditching their Sunday Best, they took on the jauntier Lorayne, Bobbe (there was a brief flirtation with the name ‘Dagmar’), and Patricia.

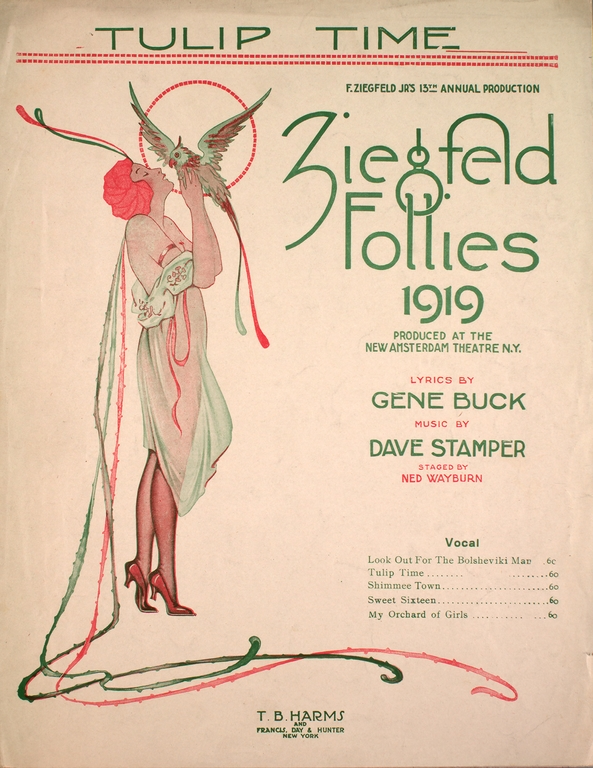

They started out early, first performing as kids in Mother Lang’s Children Show, but it wasn’t long before they took to Broadway in 1921, where an American composer, Irving Berlin, was putting on a series of shows called the Music Box Revue. It was on this stage that they’d get their first hit with an interpretation of “Everybody Step”, a rendition that Berlin loved so much, he brought the sisters back for the Music Box Revue of 1923 and 1924, tailoring songs to their jazz-tinged performance with a certain Southern twang. Cast in The Cocoanuts with the Marx Brothers, they sang another Berlin hit, “Monkey-Doodle-Doo”. And after that? It was the Ziegfeld Follies.

The Ziegfeld Follies were a series of elaborate productions on Broadway from around 1907 to 1931, and were inspired by the Folies Bergère from across the pond in Paris. You could call them a kind of variety show, only better. You know the famous Ziegfeld Girls and those tableaux vivants? That’s the Follies. And the Brox Sisters were only one group of many to make a name for themselves on its stage.

But when the talkies came around, they made the leap to the big screen in the famous Vitaphone shorts – their honey-like low voices were perfect for the early sound medium. After this came several feature length films like King of Jazz (1930), and Spring is Here (1930). Now prolific stars on stage, screen and radio, the early 30s would instead see them disband – each disappearing, like so many great things, off into married life.

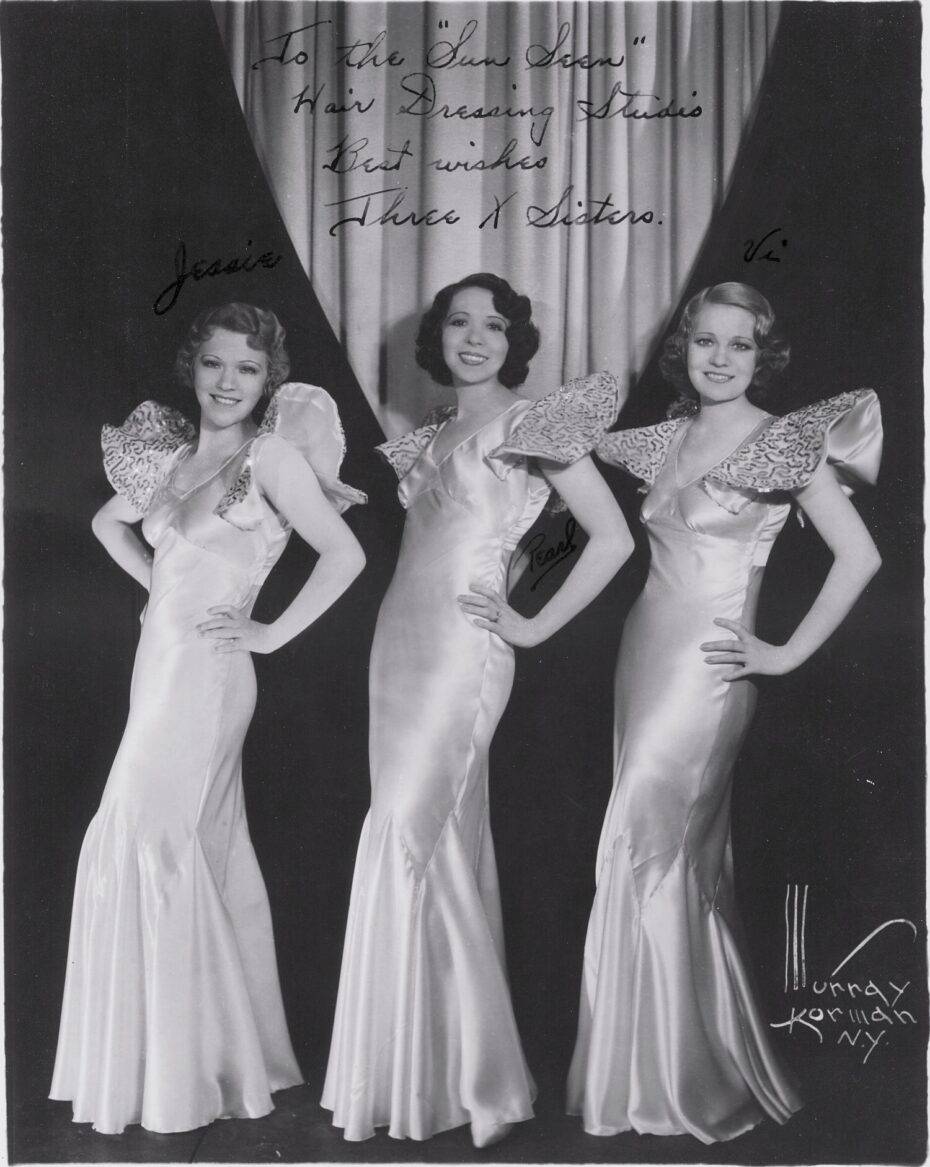

Now, let’s meet the Three X Sisters. Initially known as The Hamilton Sisters and Fordyce, due to them not actually being sister sisters, they took to the stage not long after the Brox Sisters. But unlike those three, the Three X Sisters found the whole Broadway thing pretty old hat by the time they formed a group.

With Pearl and Violet (the Hamilton’s) having performed back in Maryland as children, and Jessie (the Fordyce) – having grown up on vaudeville stages across the US, performing, they fittingly made their debut on the vaudeville stage, touring with the likes of Helen Schroeder and Anna Mae Wong. Having gained enough popularity back home in the States, the Three X Sisters made the leap across the pond to tour in Europe, selling out stages across the Continent.

By the early 30s they were back in the US, and showed no inclination of stopping. They toured the US with various bands for a while, and then took on movie shorts at the weekend. With the departure of radio favourites like the Brox Sisters, they became the top harmonisers on the airwaves, gaining steady work despite the onset of the Great Depression. By 1938 they were still headlining the top vaudeville houses in the country, like The Palace in New York and The Stanley in Philadelphia.

They even held stints performing shows at places like the Hotel Astor and the Waldorf Astoria, much in the same way that Adele or Britney would go on to headline resorts in Vegas. They slowed down by the time the 40s came around, each one going off to do their own thing. But back in the early 30s, there’d been another girl group knocking around at the same time…

The daughters of a former vaudevillian, Martha, Connie, and Helvetia were raised in uptown New Orleans with a love of music passed down to them by their family – their parents and aunt and uncle had sang together as a barbershop quartet, once upon a time. Trained in the more classical side of things, it didn’t take long for the Crescent City to rub off on them, as Martha would go on to say in a 1925 interview with the Shreveport Times, “the saxophone got us.”

As young girls, their mother would take them to see the leading African-American performers of the day at the Lyric Theatre, including the iconic Mamie Smith and her Crazy Blues. Before developing her own vocal style later on, Connie would imitate Smith’s style on the sisters’ first record, I’m Gonna Cry (Cryin’ Blues) as they began to gain popularity at local vaudeville theatres with their classical act twisted with jazz. At this point, the girls were still young. Martha was 19, Connie 17, and Helvetia – known as Vet and the youngest of the three – just 13.

New Orleans couldn’t hold them for long, though. By 1928, they were living in Los Angeles and had a contract with KNX, a radio station that broadcasted from the Paramount Pictures studio lot. By 1930, they’d switched to Warner Brothers’ station, KFWB – the same station that would play a role in the early careers of Bing Crosby and, later on, the Beach Boys. It was while they were in LA that they got gigs – where else – singing for other performers in movie musicals like They Learned About Women (1930) and Let’s Go Places (1930).

As their popularity grew, not everyone was fond. Thanks to their jazz influence, their approach to performance involved a lot of unique arrangements, with tempos and keys often changing mid-song in their signature improvisational style, and some listeners did not like this. The radio stations would receive furious letters complaining that the sisters were butchering their favourite songs.

After their stint in LA, it was time for the bright lights of New York, New York, where they landed a year’s contract with NBC. This is what would gain them attention on a national scale. It’s also where they’d go on to produce the Brunswick recordings with Brunswick Records, regarded today as milestones for jazz. All in all, the 30s saw them rack up 20 hits, two European tours, and even feature in CBS’s inaugural broadcast. The Boswells, in the end, were one of the first hit acts of the mass-entertainment age. Oh, and they just happened to heavily influence someone you might know, a certain young Ella Fitzgerald…

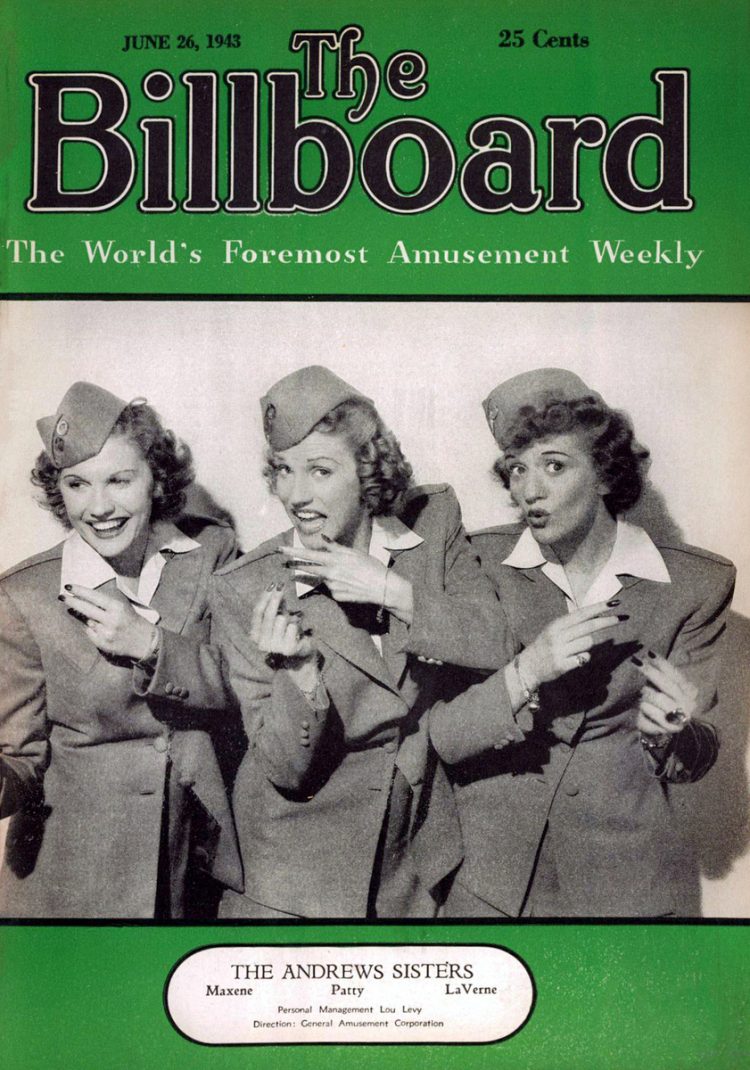

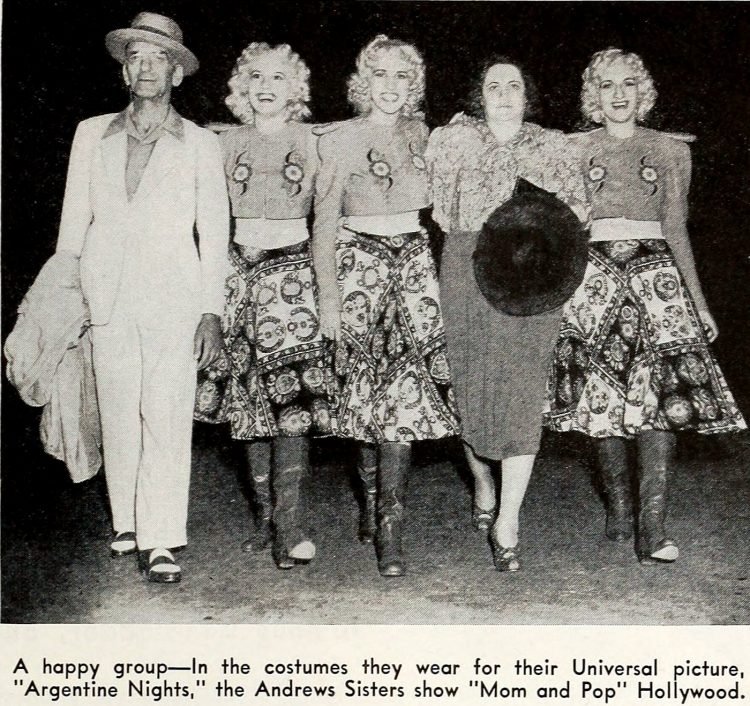

Patty, Maxene, and La Verne Andrews – known as the Andrews Sisters – took to the road in the early 1930s, starting out just as the Boswells reached their zenith, to support their parents when their father’s restaurant collapsed. They did this by singing in imitation of the Boswell’s. After a stint doing vaudeville, in 1937 they came to national attention with their radio broadcasts and first record hit, “Bei Mir Bist Du Schon”, a Yiddish tune whose lyrics were translated into English by Sammy Cahn and harmonised, many said, to sheer perfection by the sisters. They had a string of best-selling records over the next two years and, by the 40s, were a household name.

Sure, the Boswells were popular, but the Andrews were launched into the close-harmony stratosphere, a launch that would see them right through the war years with evergreen favourites like that “Bugle Boy from Company B”, an association that would stick with them for the rest of their career and bestow on them a firm fondness, like so many things that shone a little of bit of light in a very dark time. Dame Vera Lynn, for example, whose “White Cliffs of Dover” remain a unifying anthem in bleak times, even today. It was during this period that they would release their biggest hits, among them “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (With Anyone Else But Me)” and “Rum and Coca Cola”. Not only did they feature in service comedy films, they went out to entertain the forces across the globe, including in Africa and Italy.

Their support for the forces didn’t end there. It’s said that, when touring, they often treated three random servicemen to dinner. If any three women could qualify for being a nation’s sweethearts, it may well be the Andrews. But it wasn’t all rosy for the three sisters. Nation’s sweethearts they may have been (and hugely successful), the three sisters – together their entire lives – began to drift after the death of their parents in the late 1940s. When Patty decided she wanted her own solo act, it wasn’t long until the trio formally split in 1953. Maxene and Laverne tried to keep the show going for a while, but after a reported suicide attempt by Maxene whilst touring in Australia, the duo gave it up.

The three sisters reunited however in 1956, signing with Capitol Records. They recorded dozens of new singles, but with rock and roll being the new thing by the late fifties, their style of music was beginning to fall by the wayside. Still, they continued to tour extensively, mainly in high end nightclubs around the world into the early 60s. In some ways, this would be the final high for the Andrews Sisters. When eldest sister, Laverne, died of cancer in 1967, the remaining sisters once again attempted a duo act, but, like before, this never quite caught on, although they experienced a bit of a resurgence in in the 70s, when Bette Midler covered their biggest hit, “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” and the two made their Broadway debut. Despite this, the relationship between Maxene and Patty continued to remain frayed, and their last performance together would be on Broadway. They would reunite only once, in 1987, when they received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Just as they’d got their start imitating the Boswells, the Andrews Sisters would go on to become the most imitated girl group of all time, and the biggest female act of the first half of the twentieth century whose effect is still being felt today. So it’s not wrong to say they formed the blueprint for girl groups as we know them today, but perhaps it should be noted that they didn’t quite do it on their own.

Written by Freya Bainbridge