Americans in Paris. Hemingway, Josephine Baker, Jim Morrison, James Baldwin, Nina Simone – these are the names and faces that typically come to mind when we think of those who left their mark on the French capital. But a bison-chasing cowboy doesn’t exactly fit the profile of the American intellectuals, writers, artists and musicians who schmoozed with Parisian society on the sidewalk cafés of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. In 1887, the man known as Buffalo Bill crossed the Atlantic with 83 “saloon passengers”, 38 steerage passengers, 97 Native Americans, 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 elk, five Texan steers, four donkeys, and two deers, according to records. He was arguably the most famous man in the world for his time – even if his persona was a cleverly marketed myth. His Wild West show defined mass entertainment, and when he brought it to Paris for the Universal Exposition, it just about eclipsed the inauguration of the Eiffel Tower itself.

In the history of odd friendships, Buffalo Bill and Rosa Bonheur might just take the cake. The American Wild West showman visited France multiple times during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where he struck up a relationship with Europe’s leading female painter. They hunted wild boar together at her chateau outside of Paris and she painted him. But beyond this comradery, Buffalo Bill’s trip across the pond highlighted France’s unlikely fascination in the Far West, which continues to this day.

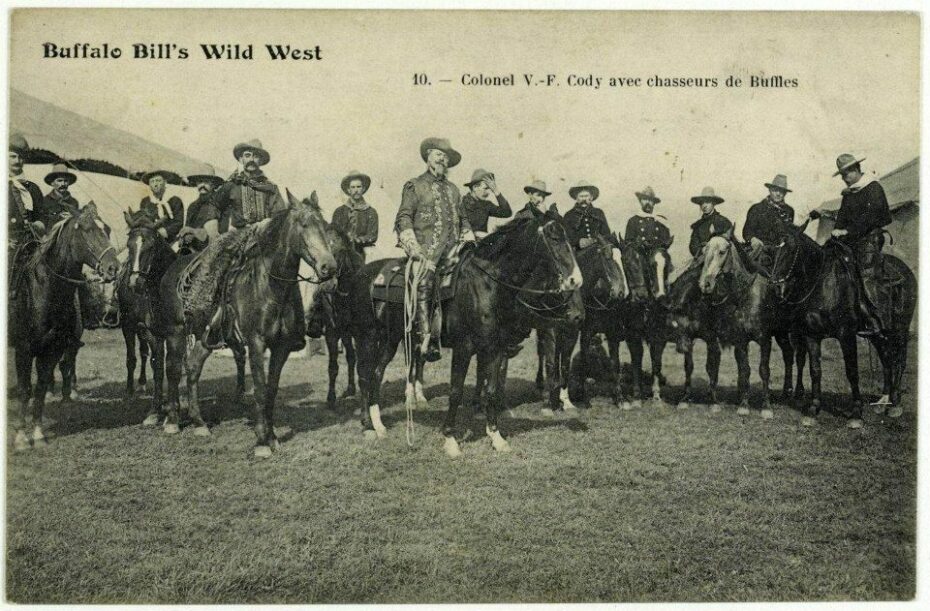

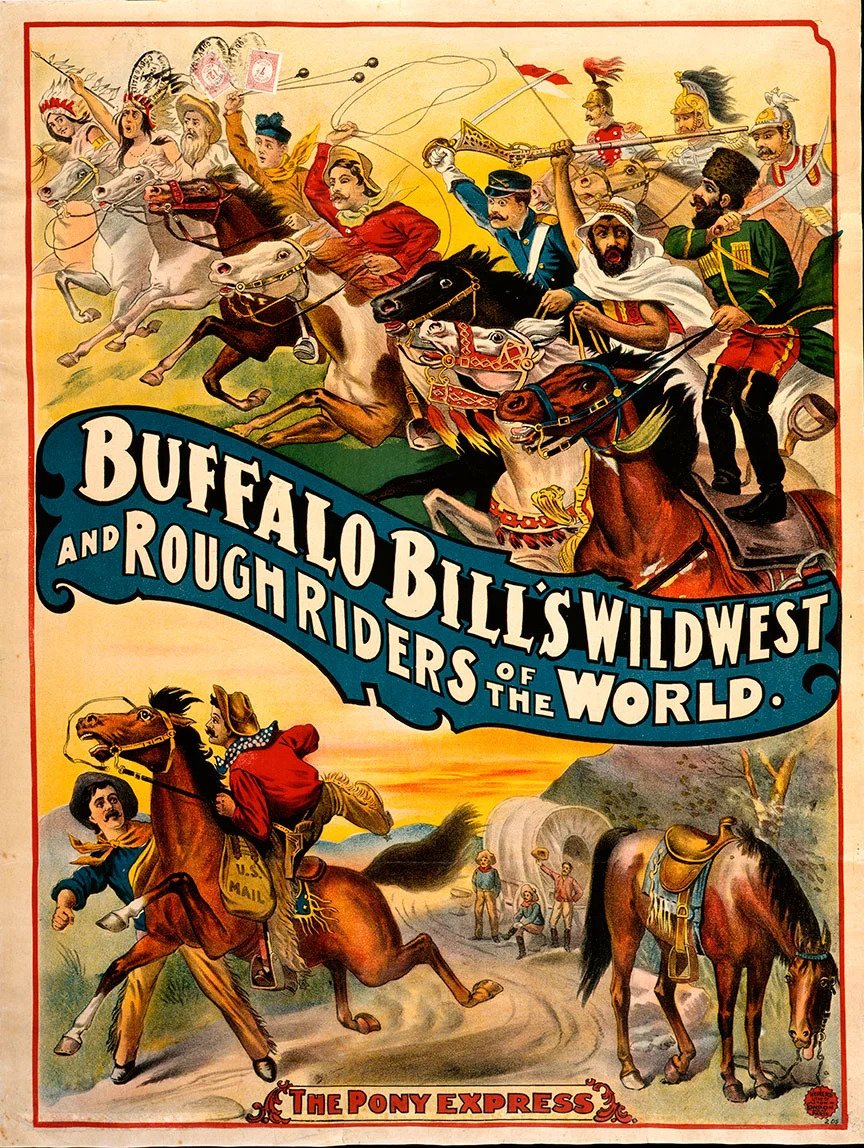

Born William Frederick Cody, in what is now the state of Iowa, Buffalo Bill was a soldier, a Pony Express rider and a buffalo hunter who garnered fame in his early 1920s through hundreds of dime novels, weeklies, plays and popular media that romanticised cowboys and pioneer life. His nickname came from supposedly killing 4,282 buffalo in a single year during the Civil War. He’s credited as the man who gave the “Wild West” its name, and in 1883, he founded Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a large touring troop that went around the United States and eventually introduced Europe to the American frontier.

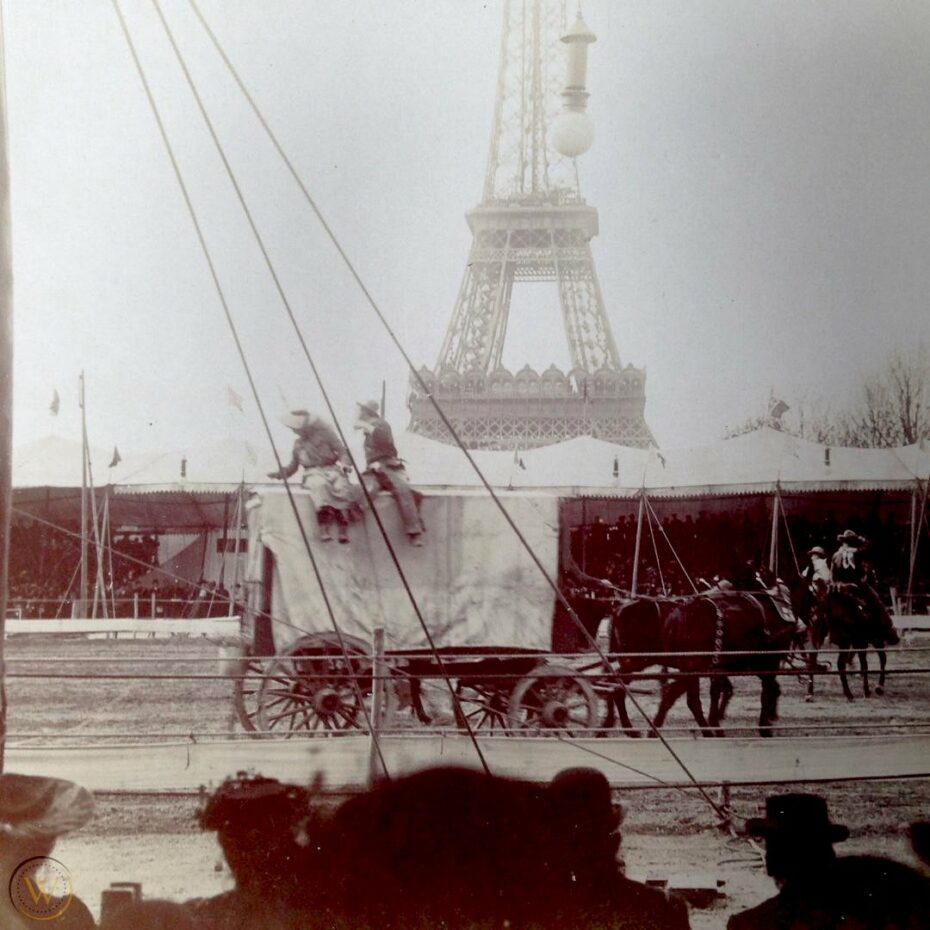

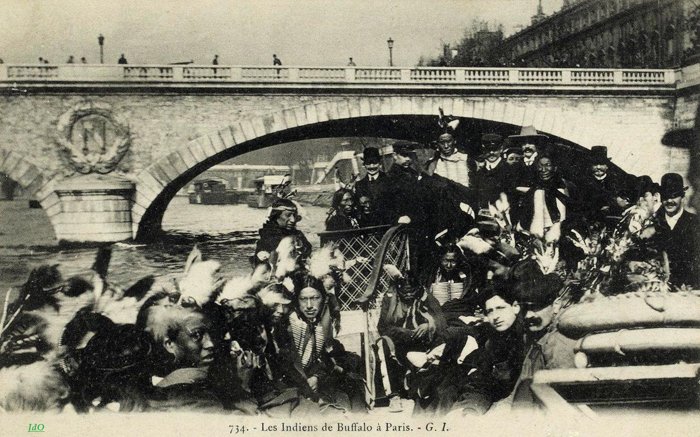

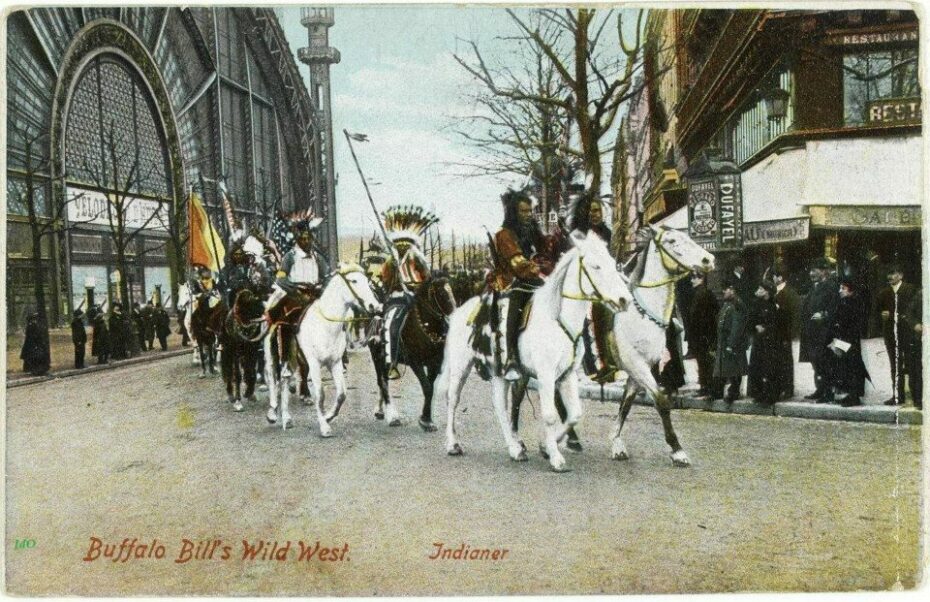

The Wild West show first came to England in 1887, the same year as Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, monetizing on a renewed European enchantment with the America wild west. It was a huge success among the English elite, with Victoria herself making her first appearance at a public event since her husband’s death. And two years later, Bill returned to Europe for the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris. His troupe were among the first people to climb the Eiffel Tower.

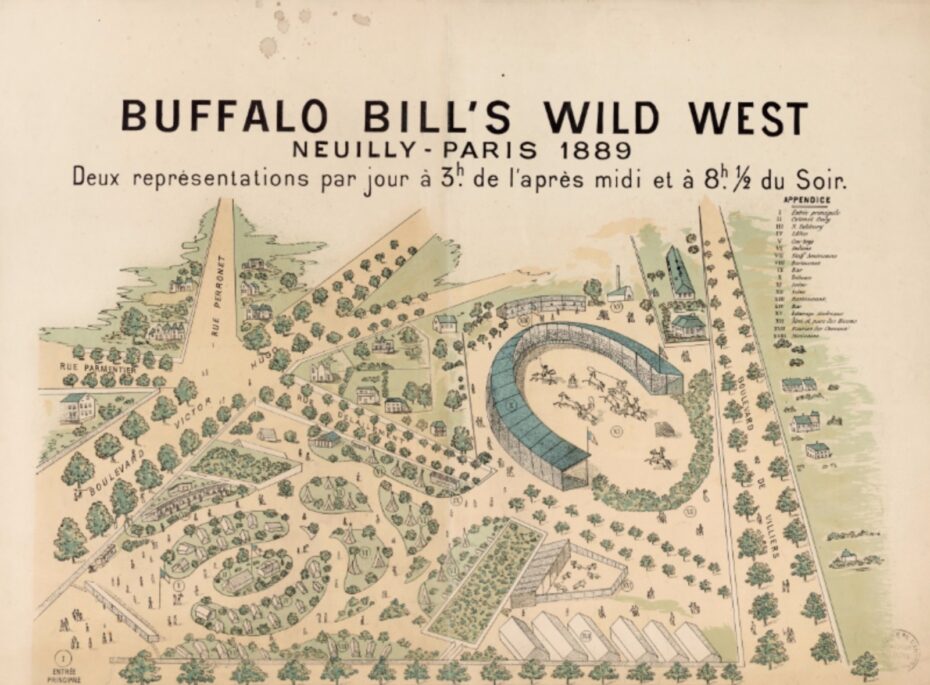

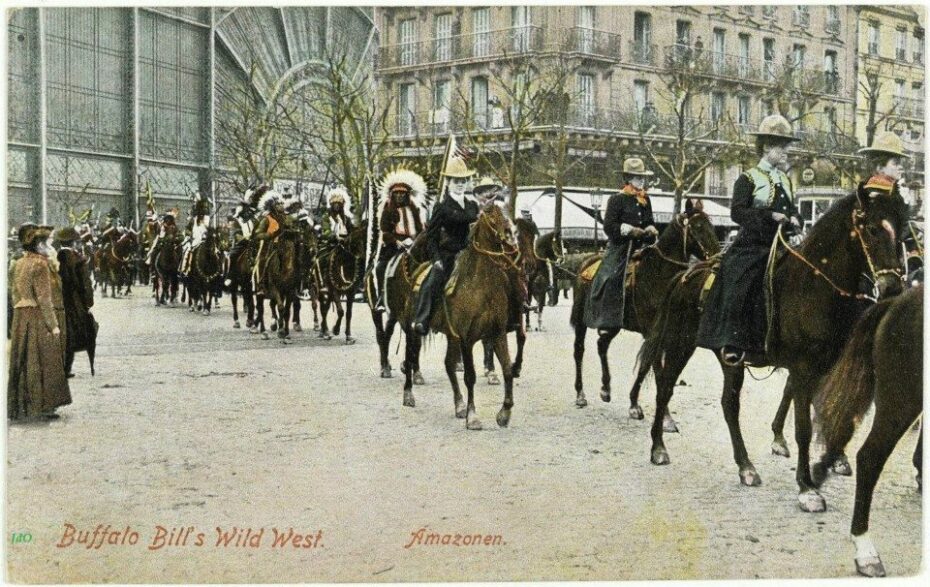

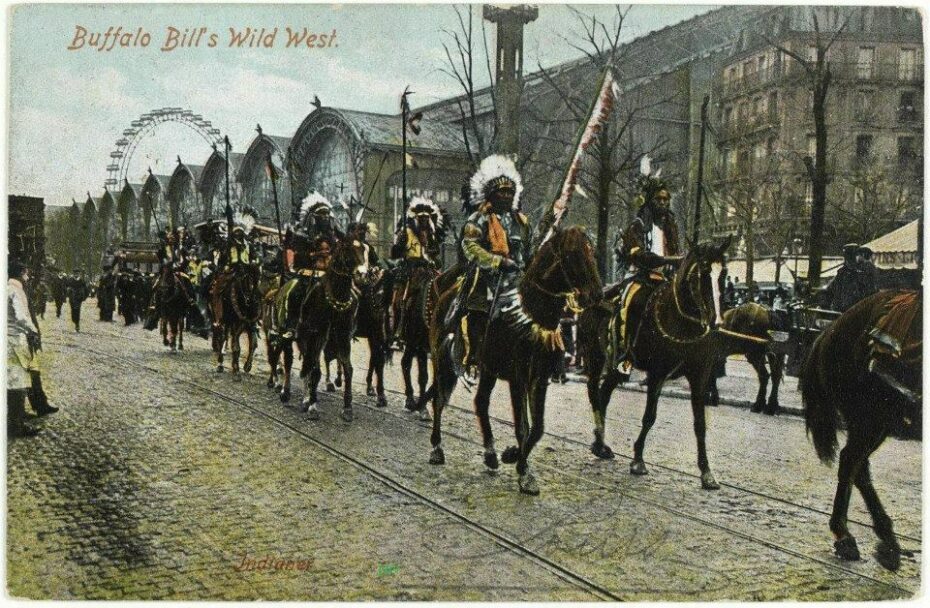

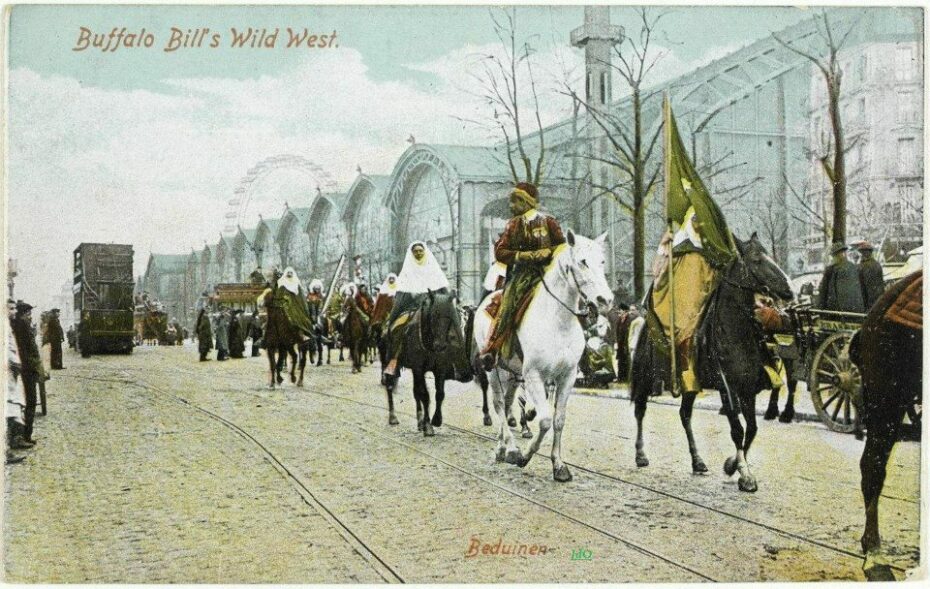

The Wild West show lasted for a full seven months in Paris. While the Iron Lady attracted roughly 12,000 visitors a day, two Wild West shows per day attracted 30,000 spectators, all wanting to experience the American West of “Guillaume Bill” – as the French called him. The show featured not only cowboys, Army men and Native Americans, but also Arabs, Turks, Mongols and representatives of other ethnic groups who showed off their horses and regional dress.

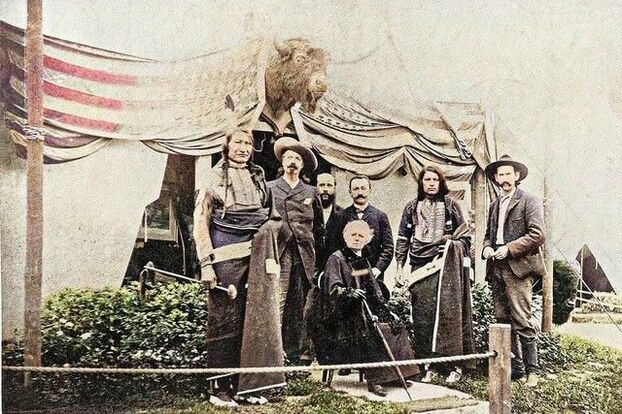

Headliners included famed sharpshooter Annie Oakley, frontierswoman Calamity Jane and legendary Sioux Chief, Sitting Bull, with a band of 20 braves. These great Sioux and Pawnee warriors who had famously resisted white domination (most notably Sitting Bull), were enlisted by Cody as paid performers to participate in his show and live in roving camps alongside the white frontiersmen they’d been battling against across the Atlantic just years earlier. Cody and Sitting Bull developed a friendship, and photographs of the two standing side by side were used in promotional posters and sold as postcards.

“Ironically, the image of the submissive American Indian also seemed obvious with the presence of Chief Sitting Bull who resisted white domination all his life,” notes a study by the Texas Women’s University. “Whether Sitting Bull’s participation was beneficial, exploitative, or one of empowerment, his participation in the Wild West Show connected Native Americans with stereotypes that would follow them for more than a century”.

Buffalo Bill’s show was a spectacle of trick riding, marksmanship displays and races, but also featured the myth of the “inverted conquest” with staged Native American attacks on white frontiersmen, depicted as the victims of their Native enemies. Buffalo Bill’s popularity, which spanned decades (and has been compared to the Beatlemania of the 1960s) would have a profound impact on cinematic and literary portrayals of the Wild West.

Jeremy Johnston, curator of Western history at the Smithsonian-affiliated Buffalo Bill Center of the West, says William Cody’s real opinions about Native Americans were conflicted. “In his writing it’s very clear there was tremendous respect for American Indians. He would tell his readers that [Native Americans] had every right to resist what was happening to them, and to fight back.” Meanwhile, for the entertainment of his audiences, the truth of settler aggression was grossly sanitised and Native showmen cast as the villains to be booed and hissed by the masses.

From Paris to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and beyond, Buffalo Bill allowed the rest of the world a glimpse at the fading American frontier, but at how great a cost? As the Texas Women’s University points out, his association and apparent friendships with respected indigenous resistors of white frontier domination introduced conflicting identities – “savage” but “noble”, “exotic” but “uncivilized”, “spiritual” but “heathen.”

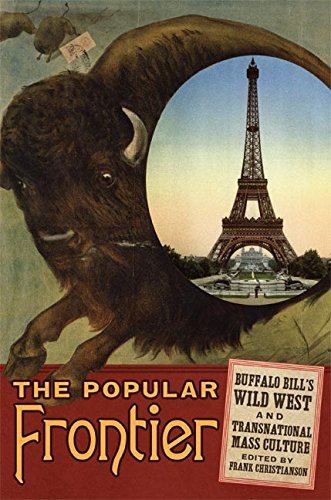

The Popular Frontier: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Trannational Mass Culture covers his global influence. As Emily C. Burns writes in the essay “Taming a ‘Savage’ Paris” from the book, “The show invited observers to make surprising links between contemporaneous trends in France-American exchange”. Paris was the next frontier for the US to conquer, Burns argues, coming at a time of heightened American tourism in France and waves of artists and intellectuals flocking to the city.

As True West Magazine reports, Wild West mania took Paris, with Stetson cowboy hats becoming the hottest fashion trend and the song “Buffalo Bill Galop” becoming a hit. Newspapers even “likened Cody’s capture of Paris to the taking of the Bastille.” One of the most impactful visitors to Cody’s Wild West was painter Rosa Bonheur, who came to sketch the exotic American animals and the Native American warriors. Bonheur was already established as a great animalière, a painter who captured animals, both epic pieces showing the strength of horses or lions but also the everyday scenes of farm life. Cody accepted Bonheur’s invitation to visit her chateau in Fontainebleau where he got to experience la chasse (the hunt) à la française, in the same forests where French kings once hunted. As the Buffalo Bill Center of the West wrote, they struck up a friendship: Bonheur painted him and in return, he gave her a traditional Lakota-Sioux garment worn by Lakota chief Rocky Bear. Belonging to one of the chiefs associated with the show, the ensemble, featuring eagle feathers, would be painted by Bonheur.

Katherine Brault, who is in charge of Bonheur’s museum-chateaux and fought for years to raise the funds to preserve the garments (still displayed there today), told Le Parisien, “Rosa was the only one in Europe at that time who appreciated the knowledge of the Native American people. For her, the people who live in harmony with nature have understood everything.”

The Musée d’Orsay is holding a retrospective of Rosa Bonheur’s work until January 2023.