The atomic age of Americana was marked by post war prosperity, white picket fence idealism, and pinup models. Lots and lots of pinup models. Rosy cheeked redheads and buxom blondes graced magazines, calendars, billboards, and even book covers. These images were as ubiquitous as they were homogenous. Often, models shared features so indistinguishable from the next that the only difference seemed to be hair colors and outfits. Especially in terms of pinup art from the 40s-60s. However, while the dominant image of the pinup model might be Blonde beauties who prevailed in the 50s, the actual history of the pinup model is much older and more diverse than we realize.

The “pinup girl” would first be conceptualized in 1895 by Charles Gibson, a Life Magazine illustrator. This woman was a reflection of Edwardian beauty standards and Gibson’s own wife. The “Gibson Girls” as they were dubbed, were voluptuous with exaggerated hourglass figures, voluminous up-dos, porcelain skin, and naturally rosy cheeks and lips. The image became so popular that pretty soon, the Gibson Girl was used in everything from advertisements to magazines.

But Black and Brown women of this era were also a part of the growing Gibson Girl trend. Vaudeville actress, Dora Dean Babbage, would become so popular for her beauty and quote; ‘plump striking figure’ that she too would be hired to advertise cigarettes and chewing gum. Likewise, stage actress Aida Overton Walker also embodied the aesthetic with her voluminous hair and curves, making her celebrated for her beauty as well as her talent.

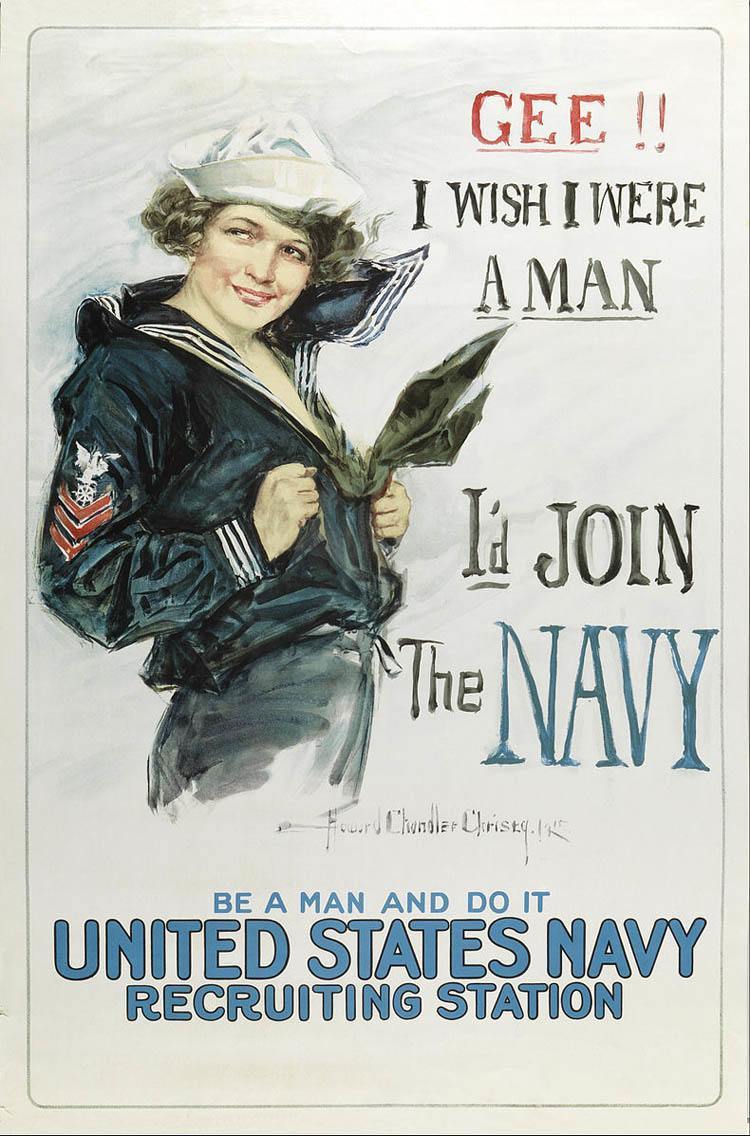

In response to this unattainable and restrictive new norm, a contradicting trend towards wearing more utilitarian clothing emerged alongside it. By 1917 what we know as the modern day pinup would take shape as advertisers began to use the imagery of beautiful women in men’s military garb to inspire patriotism in American men. The sexualisation of the Gibson model would also become more overt as pseudo suggestive slogans like: “I want you…to join the Navy” would be plastered next to images of women in feminized military uniforms. Black and Brown women, whose image has never been synonymous with All American Beauty, did not have their image co-opted for this sort of propaganda.

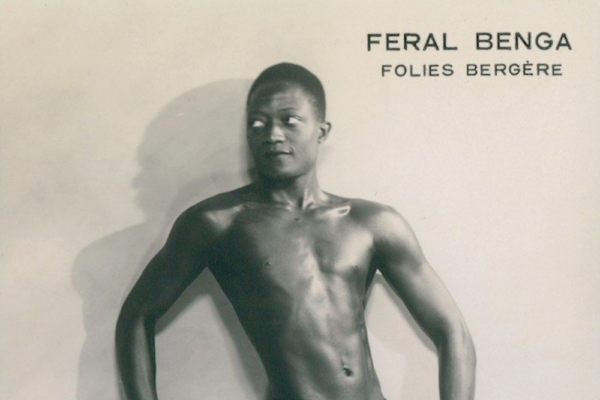

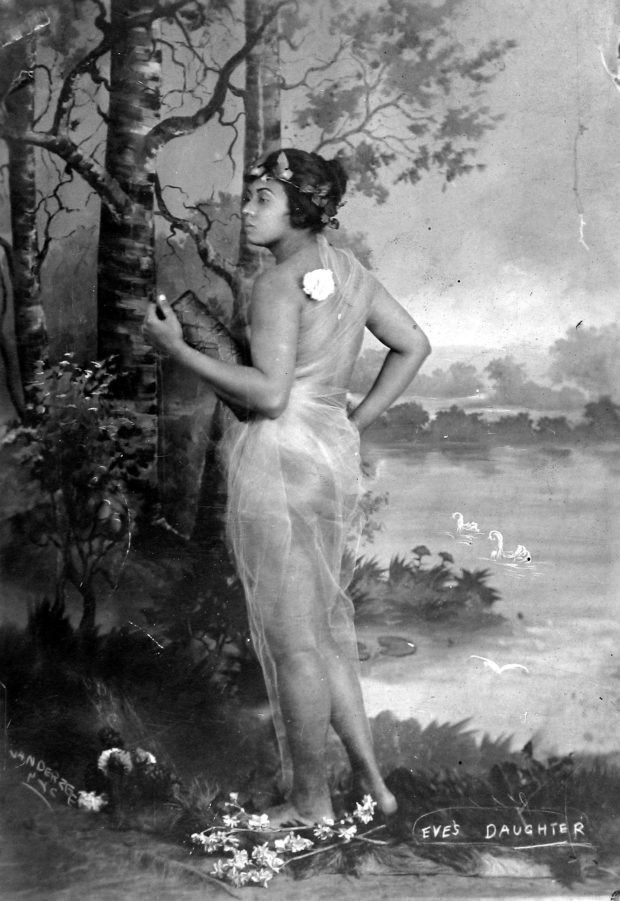

The 1920s and 30s would usher in a new found era of freedom for women which would be reflected in the imagery of models. Now, flappers with their above-the-ankle dresses offered new titillating material for photographers and illustrators. Actresses like Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, and Jean Harlow posed suggestively for promotional stills of new films and plays while underground photography studios mushroomed across cities to cater to the growing thirst for more risqué media. In the case of James Van Der Zee, he would pose a number of Black beauties for a collection of nude photos with titles such as “Black Venus.”

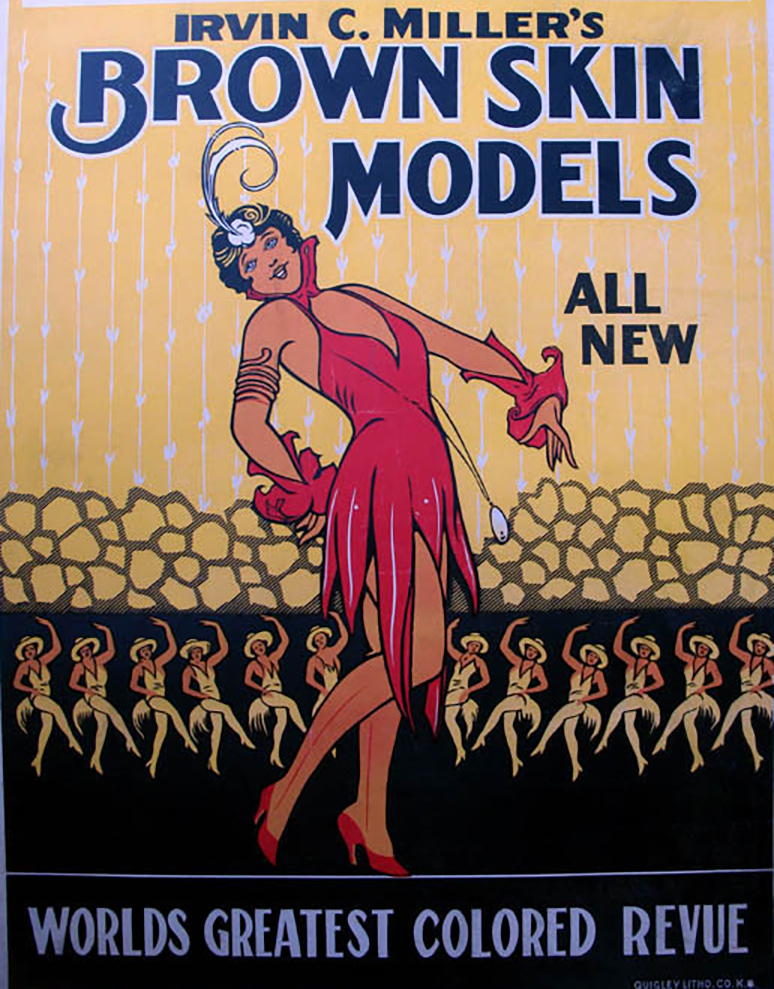

Similar to White stage and screen actresses, Black burlesque dancers would often pose nude or scantily clad to promote their roadshows and revues. Performer Kahloah would do just that for the all-Black revue Blackbirds circa 1935. It was also not uncommon for these burlesque dancers to lend their image to cosmetics brands like Blanche Thompson, wife of vaudeville producer Irvin C. Miller, who endorsed Lucky Hearts Cosmetics.

As the 1940s rolled in, so did WWII. This is where the ubiquity of the pin-up image, also sometimes known as cheesecake photography, would really begin to be felt as now, these ever cheerful vixens would be painted on planes, helmets, calendars, advertisements etc. Their image was meant to give the boys back home something to fight for. Something to look forward to coming back to. Something that women of the 1950s would have to deliver on.

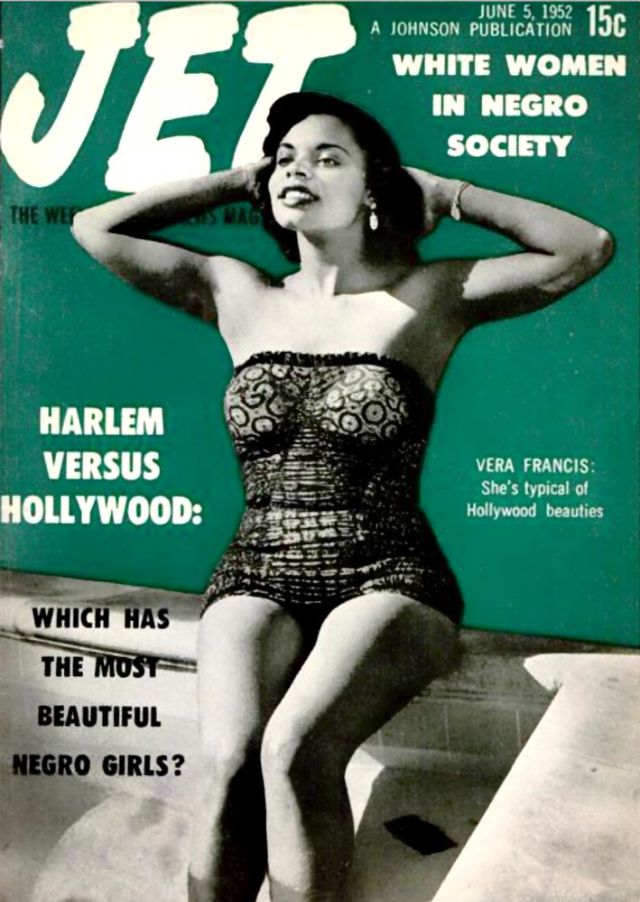

After the success of WWII, Americans were experiencing unprecedented economic prosperity. There was also a new found curiosity surrounding sex that may have, in part, been ushered in by the ever present image of the pin-up girl. In the Black community, this curiosity was felt and Black magazines founded during this decade rose to the occasion by offering their very own Black pin-ups. Jet Magazine featured a beauty of the month much to the excitement of male readers and aspiring career women, who used the opportunities to break into modeling or acting. Some of the girls were college students or girls with career aspirations that had nothing to do with modeling, who simply wanted to make a few extra bucks.

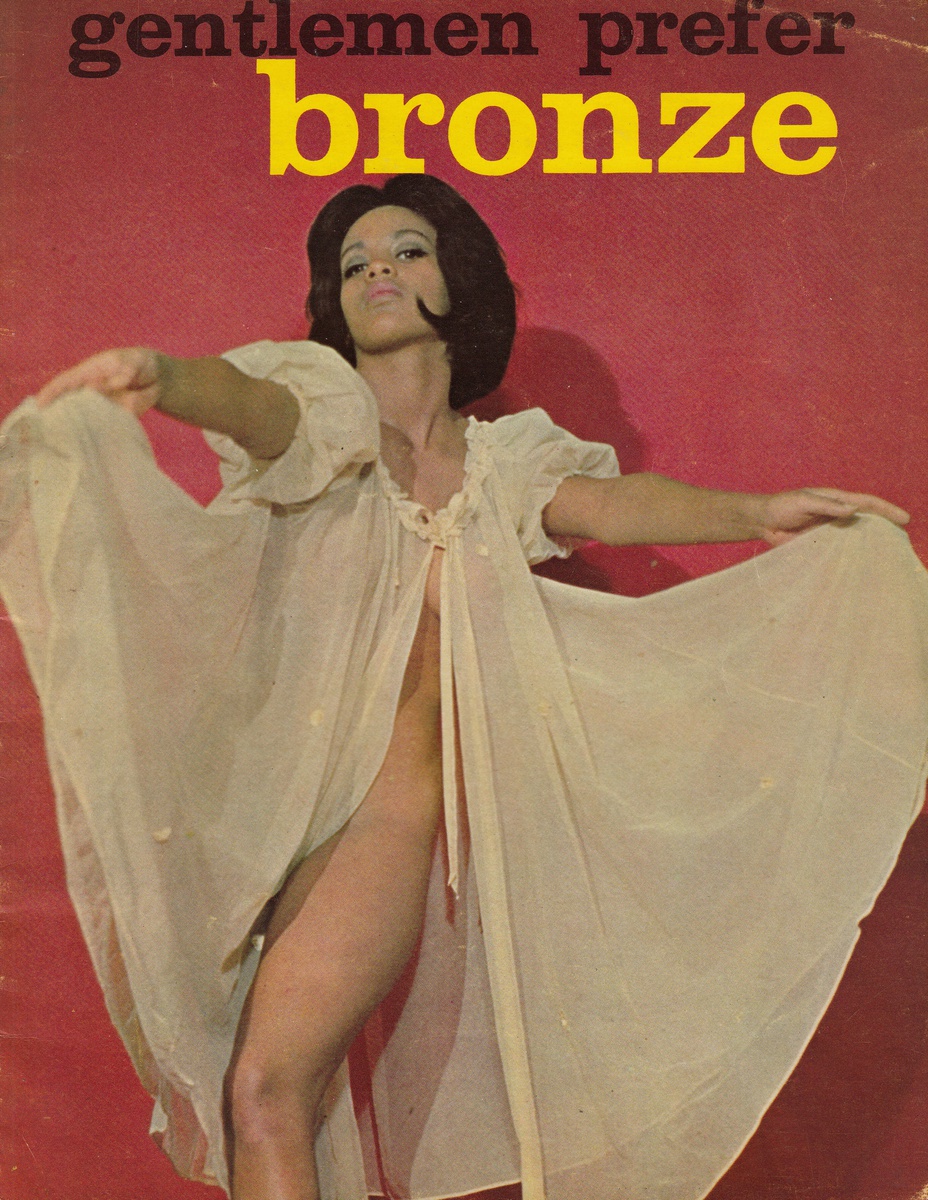

Shake dancers, the Black community’s answer to burlesque, were often the centerfolds and cover girls of these publications. Their provocative careers and sexy image provided journalists with no shortage of material, and the press covered their private and professional lives closely, offering tantalizing photos of women next to write-ups on their dating lives and career moves. Duke Magazine, an upscale men’s magazine for Black men, would be published in 1957 and was considered Black people’s answer to Playboy. They would include the first full color centerfold of a Black model.

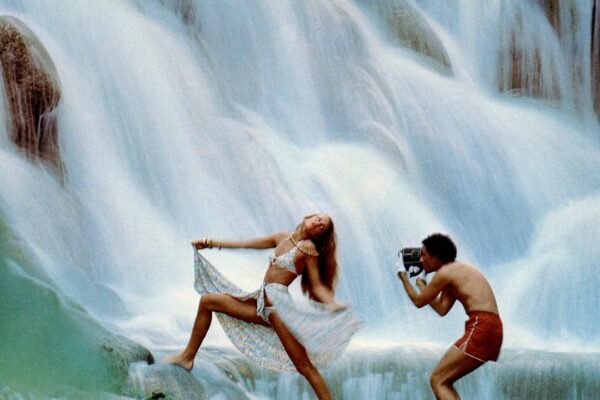

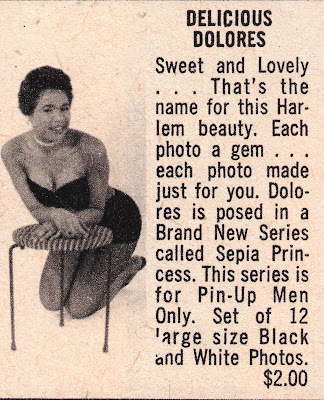

For men wanting to see a bit more skin, there was Cass Carr’s secret camera club, which offered sexy pictures of ebony models which were sold in secret and under the guise of being ‘figure studies’ for artists. The Harlem-based photographer Cass Carr is rarely credited as one of the first photographers to hire Bettie Page as a model. She was actually arrested at one of his shoots in 1952. The 1960s and 70s would bring about an all-out sexual revolution which rose alongside the “Black is Beautiful” movement. In response to this, Black models were now more sought after than ever before, both for runway and for pinup – at least in their own communities that is. In 1965 Jennifer Jackson would become Playboy’s first African American Playmate. That same year, Playboy would open a resort in Jamaica.

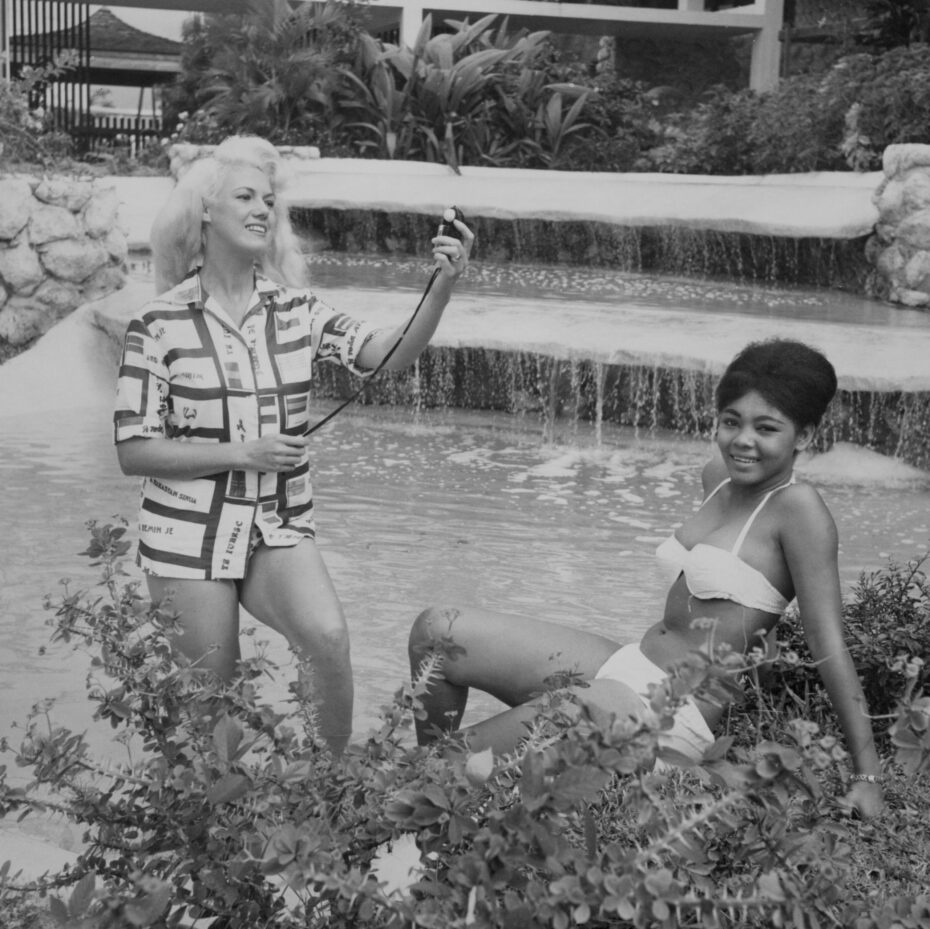

For this venture, Hugh Hefner employed former pinup model turned photographer, Bunny Yaeger, to snap pictures of his Jamaican bunnies. Bunny had already been photographing other beautiful Black women for several years to stand in opposition to racist 1950s culture. But when it came to selling the photographs, white publications wanted nothing to do with Black pinup models and Black publications would not buy from a white photographer. Yaeger’s work with models of color has only recently begun to be examined and much of it remains unseen by the public.

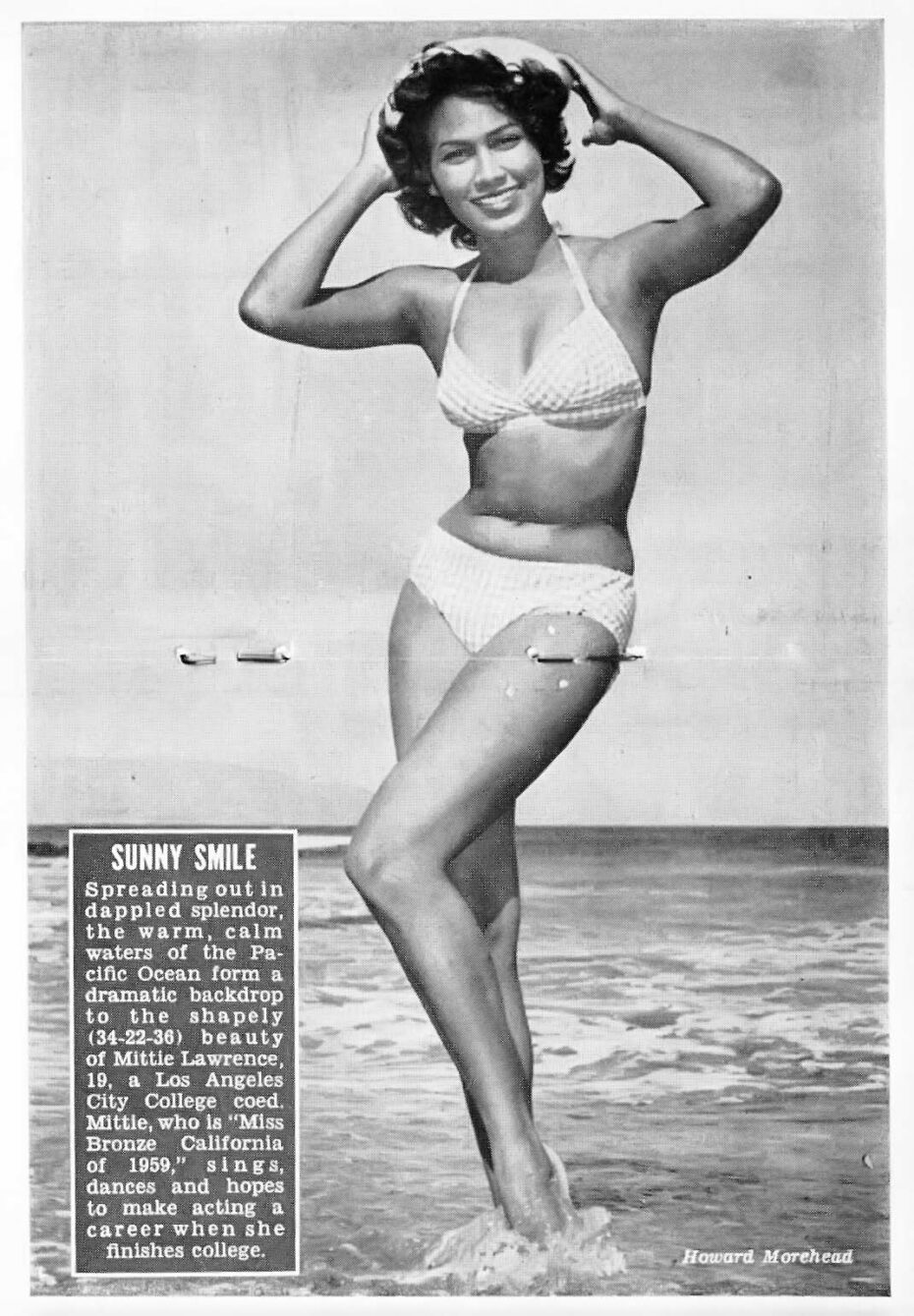

The rise of Black pinup photography was in part spawned when pioneering African American photographer, Howard Morehead, overheard another photographer proclaim that it was “next to impossible” to supply attractive Black models for fashion and pin-up photography because there “weren’t that many attractive Negro girls who had charm and were photogenic.” Morehead founded the Miss Bronze California beauty pageant as a reaction to the systematic discrimination faced by African American women and his photographs were frequently featured in Jet and Ebony magazines.

This belief kept Black women shut out of the world of pin-up modeling despite the fact that Black models had been doing it for as long as the concept had been around. The 80s through the early 2000s would see the most dramatic shift in pin-up culture as new forms of media ushered in a new type of pin-up. The video vixen would become a prominent fixture of the African American community during this time and would be something of Black people’s answer to the pin-up model of yesteryear. Like their predecessors, these women’s provocative careers spawned curiosity and intrigue. It was not unusual to see these Black models being interviewed on television or attending prominent red carpet events in the Black community such as the Soul Train, BET, and Hip-Hop awards. They were the endorsers of fashion brands and the cover models of magazines catered to Black men. Their images were shared on websites and online forums and many of them used the notoriety to build nest eggs for their futures.

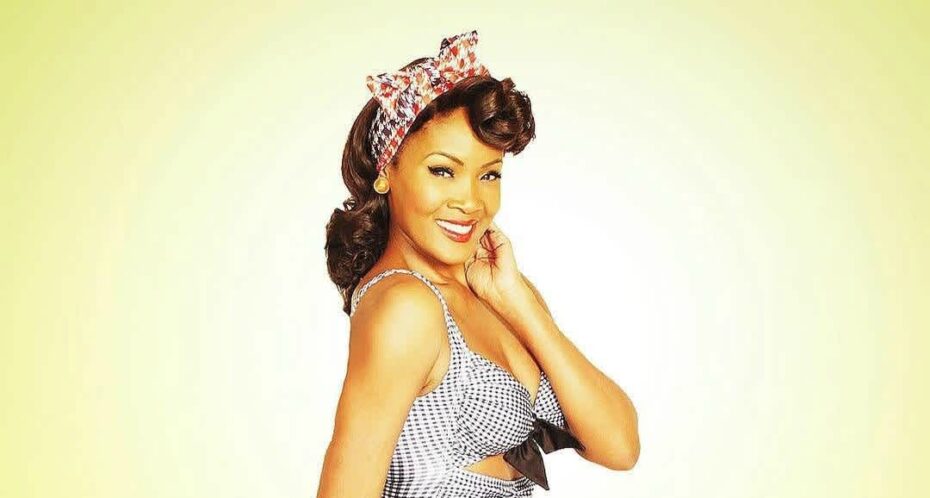

As the 2010s rolled in and social media became a permanent part of American life, the pin-up model was driven almost exclusively online. Instagram models were soon to be the new ‘pin-up girl’ as print media fell out of favour. There was however, a renewed interest in burlesque ushered in by the likes of Dita Von Teese and influential vintage enthusiasts. Slowly, but surely, a new generation of pin-up models, photographers, shake dancers, and burlesque performers emerged in the decade to come.

“Given the time periods in which subcultures like Neo-Rockabilly and burlesque take inspiration from, and especially white-washed history’s selective memory, many blacks don’t feel an affinity for retro revivalist groups,” writes Carmilla De Rosa of The Pin-Up Club. “However, there are a few prominent black women in these movements who are reclaiming their history and representing women of colour”.

In 2013, Candace Prioleau would create Black Pinups Magazine in response to modern pin-up publications almost exclusively publishing white and non-Black models. The issues feature notable Black figures in the pin-up and burlesque communities including: Angelique Noir, Perle Noir, and jazz singer Tammy Savoy. Modern shake dancers and models like Bebe Bardot, Elexus Jionde, Nikki DaVaughn, and Chicava Honeychild have also worked hard to create timelines that chronicle the contributions of Black women to the art form of pin-up / cheesecake modeling and burlesque.

“I believe when you hear the words burlesque dancer or pin-up model you have a certain image embedded in the brain. The faces for pin-up models and burlesque starlets have always been beautiful white women. I think that as long as this image is the mainstream prototype then the men and women of colour will always receive a limited amount of publicity, even if their talent or beauty surpasses their counterparts. However, we have so many resources that our forefathers and mothers didn’t acquire. I encourage every performer – black, white, yellow or green – to take back your power and put your destiny in your own hands … We have the power and responsibility to learn from our past.”

– Perle Noir (via Pin-Up Club).