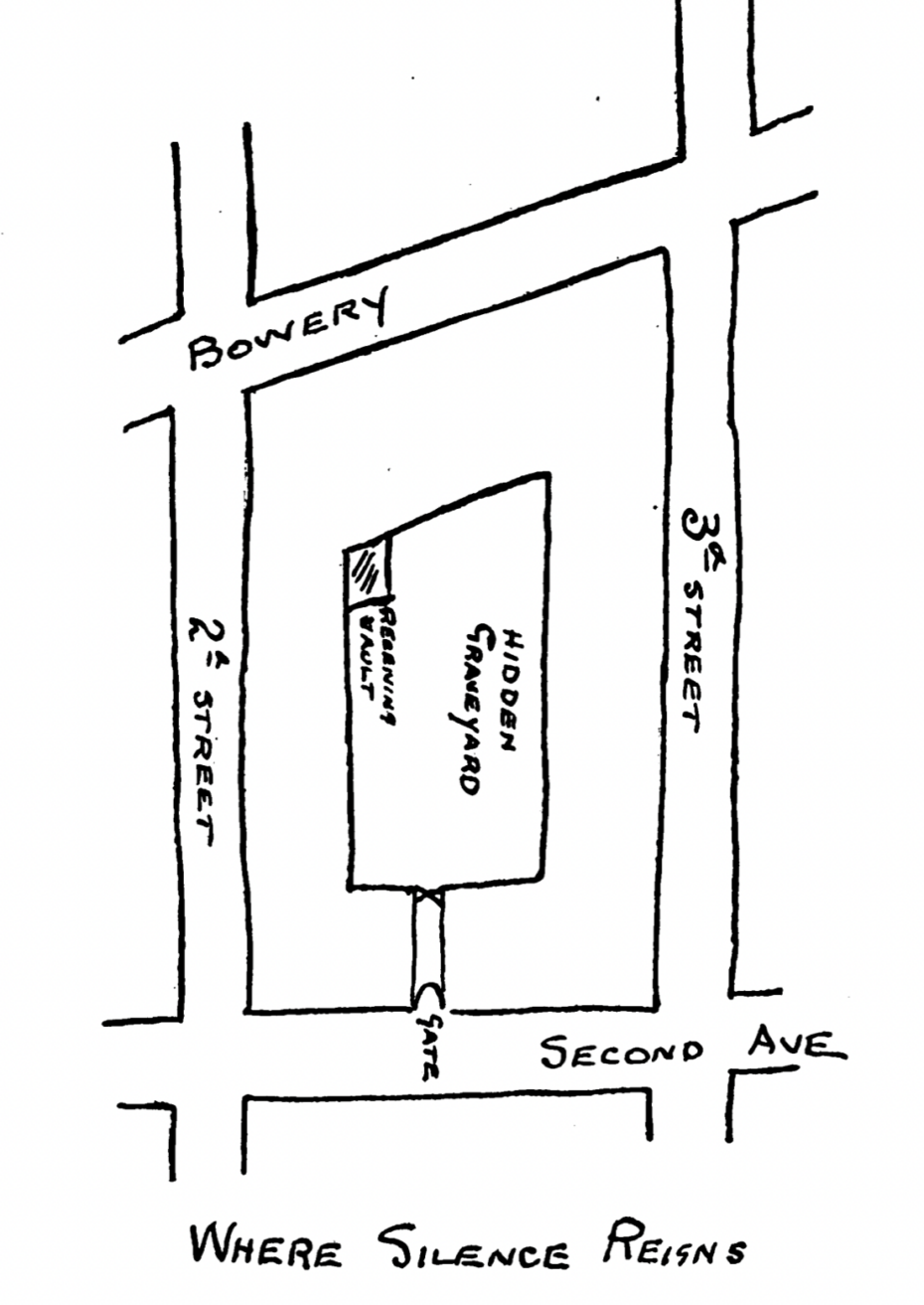

We are exploring New York City with an old hand drawn map that bears the mysterious legend, ‘Where Silence Reigns.’ Roughly sketched out over a hundred and twenty years ago, it shows just four streets. Like a pirate’s map of old, it has an ‘X’ marked on it, but this map marks the spot of buried treasure of a different kind – a long forgotten and abandoned graveyard.

We’re on the trail of this hidden graveyard in the midst of Manhattan’s bustling East Village. Walking down the noisy Bowery, it is hard to imagine silence reigning anywhere, just as it must have been when the map was drawn back in 1899. The man who made the map picks up the tale :

“In this part of the city, the houses are so thickly bunched that not a foot is spared for even a bit of green, and if a few blades of grass struggle out from between the brick-paved courts, they are ruthlessly ground out of existence by heavy shoes, as if they were some poisonous and hurtful thing.”

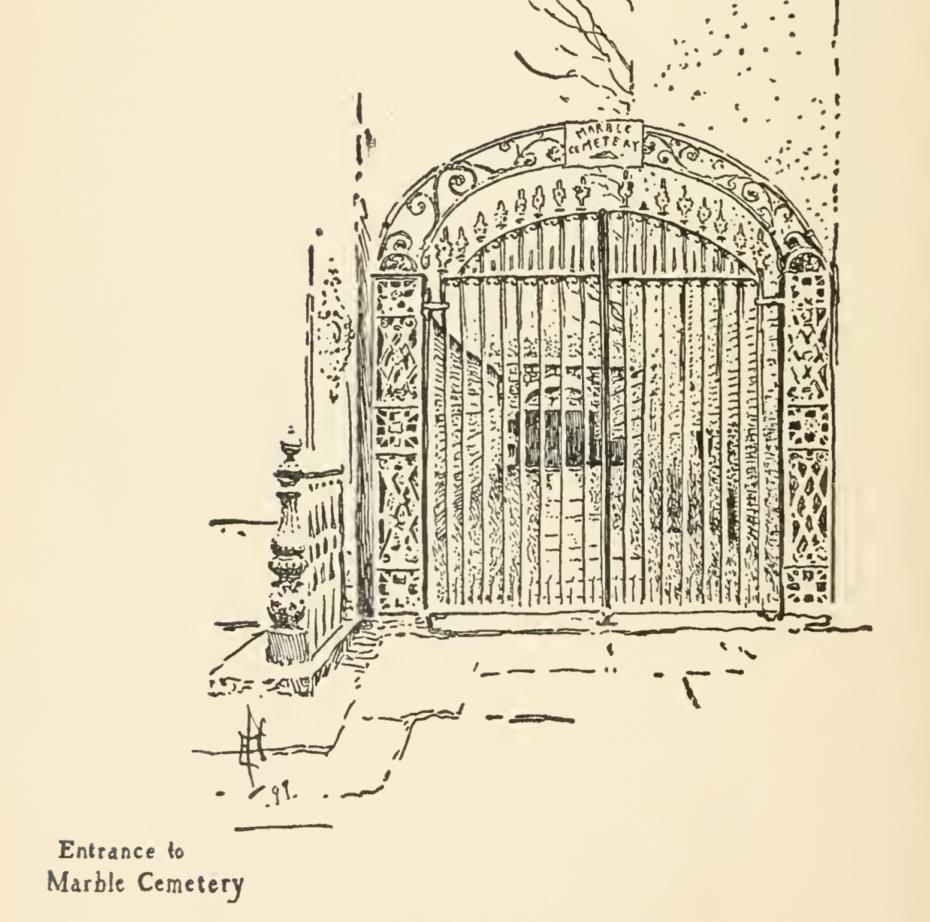

The location marked on the map takes us to Second Avenue, between Second and Third Streets, to a small ornate, wrought iron gate set back from the street. Today, it is quite visible to passersby if not a little unknown; back in the late 19th century it was overgrown, boarded up and hidden…

“I had noticed an iron gateway set in between two houses…cramped between the tenements…a gateway of a bygone day, tall with rusty bars of an ancient pattern…standing beside the closed gate with never a chink of broken space through which to peep at what was beyond.”

Our enterprising map maker found a way to get past the locked gate by spying an open tenement door, tiptoeing through and climbing over a back wall, where he found something remarkable.

“Having gone so far, I made a discovery – amidst a solid mass of brick and mortar of the tenements, hid a long-forgotten cemetery. So shut in by dwellings that to one who walks the near-by streets, unconscious of its existence, it is as completely lost as though it had never been.”

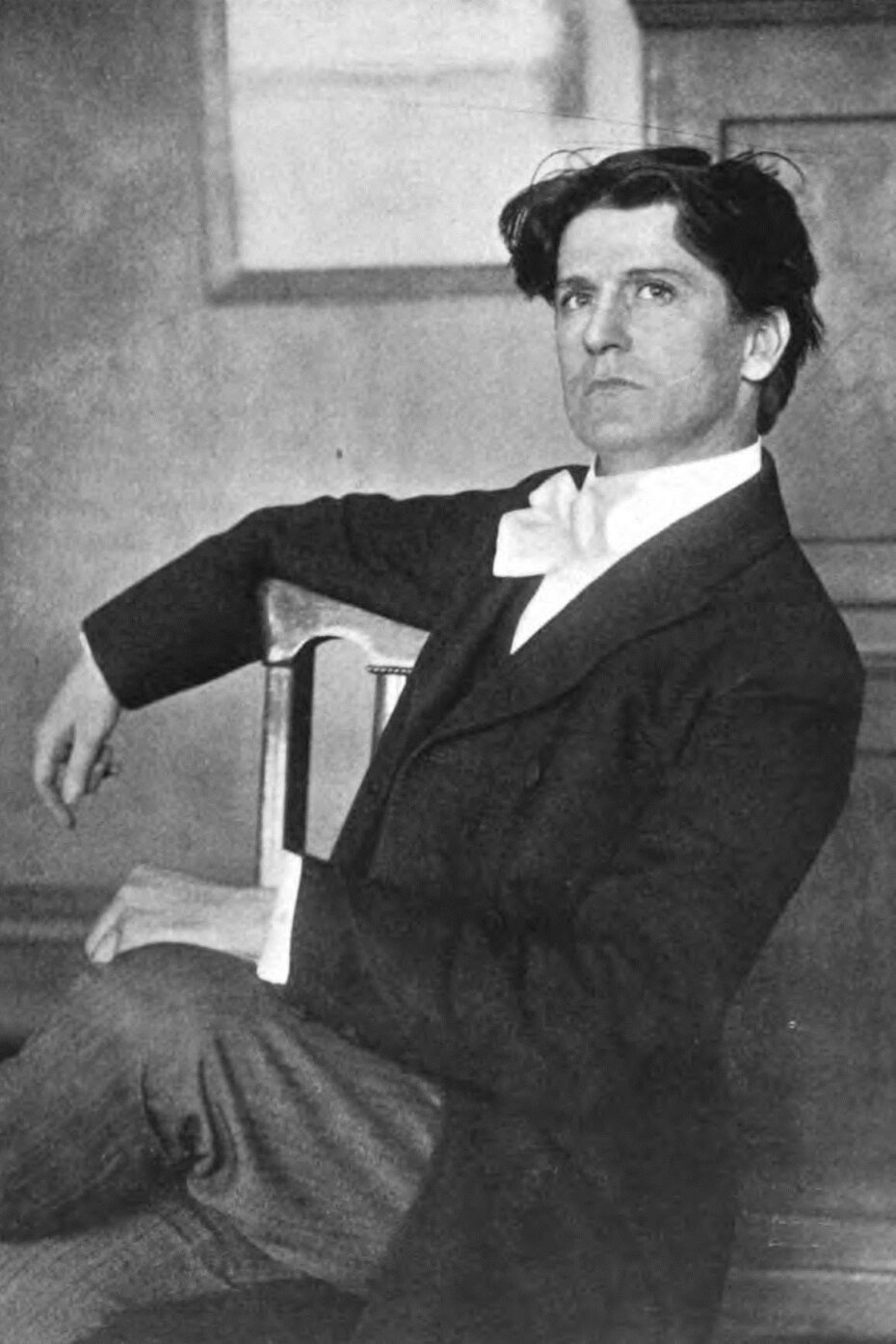

Our adventurer had just come across what was then, the abandoned Marble Hill Cemetery, New York’s oldest non-sectarian graveyard and of the smallest burial places in the city. His name was Charles Hemstreet and he was perhaps New York’s first urban explorer.

Urban exploration may seem like a fairly recent pastime, an underground community of adventurers in search of ruins, abandoned buildings and forgotten tunnels lying underneath the cityscape. But this discovery was made back in 1899, when Hemstreet went in search of old buildings and overlooked corners of Manhattan that were already being lost to unrelenting urban development. Back then, as today, beautiful buildings from New York’s past were being regularly demolished and replaced with ones anonymous and plain, rendering the great city virtually unrecognisable from one generation to the next.

Listen to Hemstreet describe this fast disappearing Manhattan in the 1890s and it could well have been written today:

“Whatever it may once have enjoyed of country green, and unobstructed river breezes, no trace of them remains. It is now a cramped and gloomy way, darkened by the structure of the elevated road from above, and by an irregular line of unattractive buildings on each side.”

Fortunately, Marble Hill Cemetery (not to be confused with a second, slightly larger cemetery with the same name several streets away), managed to survive, and today is a lovingly tended, yet still secluded cemetery in the East Village. Usually under lock and key, it is open about once a month between April and October, where you can step inside, and marvel as this ‘Place of Internment for Gentlemen’.

At the end the nineteenth century, Charles Hemstreet, a man after our own heart, scoured the city in search of other such hidden gems, writing his discoveries in books little known today such as “Nooks and Corners of Old New York”, and “When Old New York Was Young”. We went out onto the streets of Manhattan, his books in hand, using them as guide to see if anything he unearthed could still be there today; following in the footsteps of a kindred spirit to all those who love to explore the forgotten corners of the city before they are lost forever.

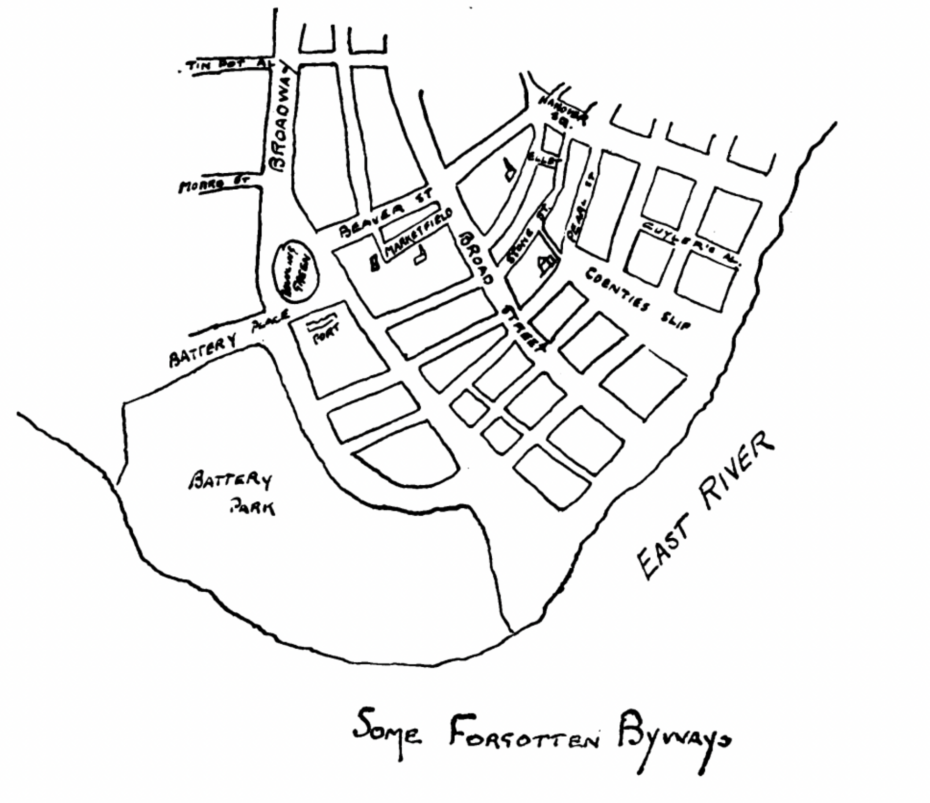

Hemstreet did much of his exploring in Lower Manhattan in what is known today as the Financial District. This is the oldest part of the city, settled as the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam in the 1600s. Whilst much of modern New York was built on its famous grid system, creating a city of straight lines, right angles and famous avenues, down in the Financial District you’ll find as Hemstreet wrote, “a confusion of streets…where various sections met at every conceivable angle”. Often the streets of Lower Manhattan, today dense with skyscrapers, still follow the original topography of the island; the unusually curved Maiden Lane for example follows the path taken by a narrow stream where Dutch ladies once went to wash their clothing, called the Virgin’s Path…

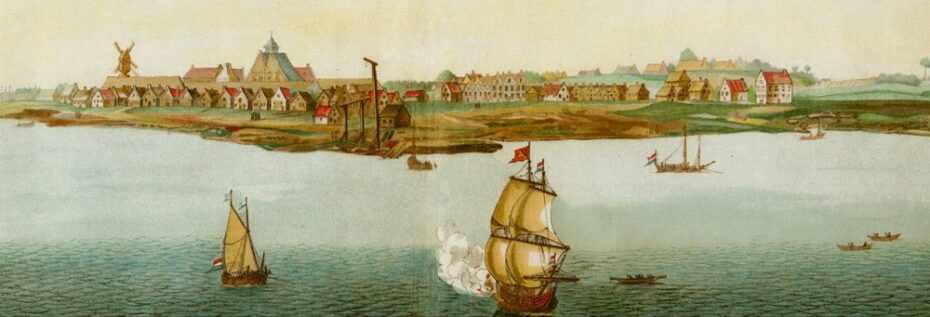

Back in 1899, the old New York Hemstreet set out to explore was already a place largely of memory. His chapters are often fruitless searches for bygone places such as, “The Pleasant Days of Cherry Hill….Some Forgotten Byways….Old-Fashioned Pleasure Gardens…..” Here’s how he described the lost village of New Amsterdam;

“Here it nestles at the lowest point of the island – one hundred and twenty as dainty and picturesque houses as an artist ever dreamed of; tiny structures one story high, some of stone, some of brick, some of wood; all with steep, slanting roofs. This, then, is the village of New Amsterdam, shut in to the north but a wooden wall, with its two gates about to be closed for the night; gates that are as the eyes of the town, for the citizens go to sleep when the gates are locked. There is just enough light to show the little town with its enclosing wall; just enough light to see the crooked, narrow streets, that have grown to their present dignity from lanes that led from house to house.”

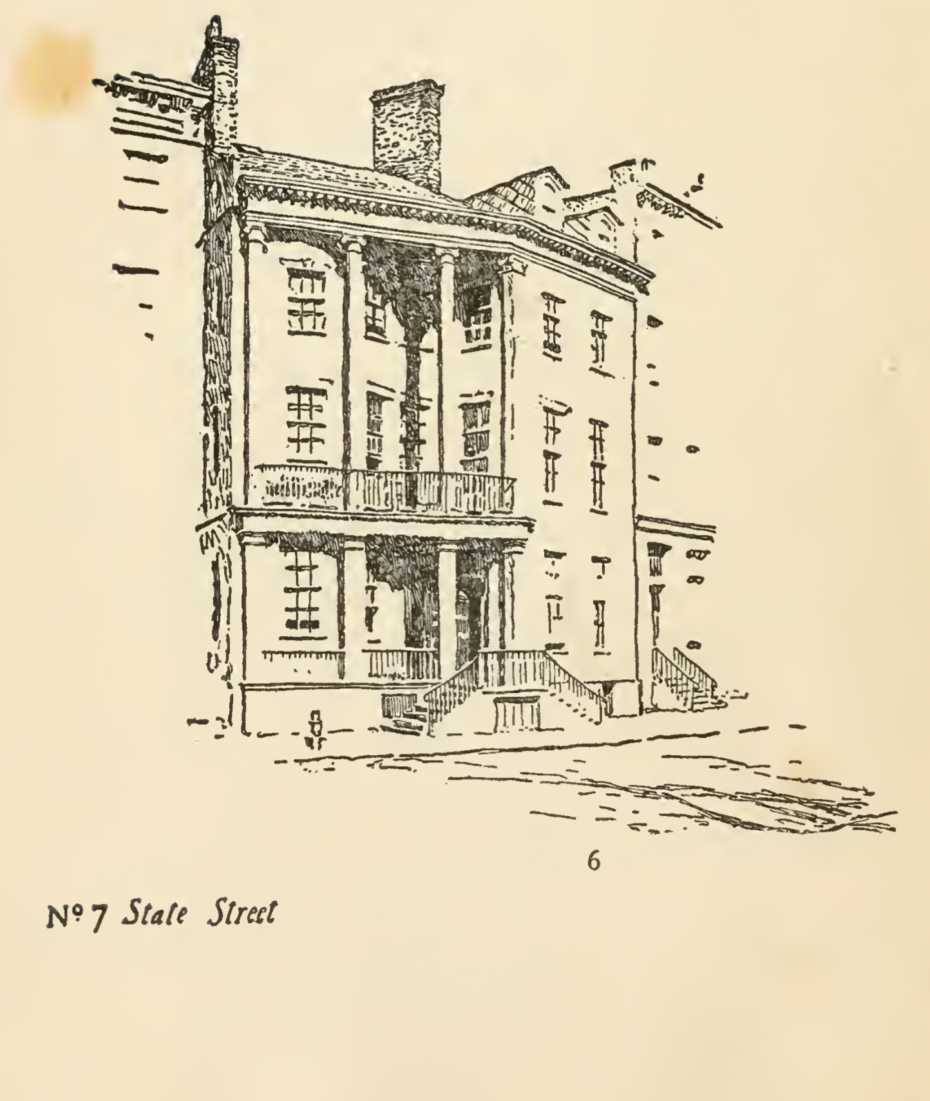

We’re beginning our adventures on one of the first streets you’ll encounter in Lower Manhattan if you were to start at its southern most point: State Street. Located opposite the bustling departure points for the Staten Island Ferry, one of the first things you’ll notice about tiny State Street is that it curves just like Maiden Lane does, gently following the contours of the waterfront. The second thing you might notice is a tiny red brick house nestled at the foot of monolithic skyscrapers. It is all that remains of what was once one of the most fashionable thoroughfares in Manhattan. State Street had been lined with mansions overlooking the harbour, but when Hemstreet searched them out in 1899 only one remained, just like today.

“The fashionable quarter of the city, and on it where the homes of the wealthy. Several of the old houses still survive. No. 7, now is a home for immigrant Irish girls was the most conspicuous on the street.”

Number 7, State Street is still there, a red bricked elegant mansion with balconies supported by columns made from the masts of old merchant ships that curves following the contour of the street. It had once been the home of Elizabeth Ann Seton, who devoted her life to caring for the city’s poor children, and became the first American to become canonised as a saint. Today the often overlooked building serves as a rectory for the church next door, but is the only surviving remnant of a once grand address.

The New York City Hemstreet went to explore in the 1890s was a far cry from the city we know today, but had already undergone huge growth. In 1801, the population stood at around 60,000. When Hemstreet wrote ‘Nooks and Corners of Old New York’, it was over one million. Just nine years before the book was published, the tallest building in the city was incredibly still little Trinity Church on Broadway, but the year his book came out the first skyscraper had been built. You can still see the Park Row building, that had heralded the start of ‘newspaper row’; today it is dwarfed by the colossal skyscrapers surrounding it.

Make your way east from State Street and you’ll enter a web of streets that is the heart of Manhattan’s Financial District. What is today the economic epicentre of one of the world’s great powers, in Dutch Colonial days had dank and salubrious beginnings: Hemstreet explains, “Beaver Street was as ditch, on either side of which was a path. Close to where Broad Street is now (home of the first New York Stock Exchange) was a swamp.” The Dutch settlers cultivated the marshlands, fields, streams and swamps into a picturesque village that wouldn’t have looked place along the coast of the Netherlands. This is what Hemstreet went in search for hundreds of years later, often in vain;

“Down that way to the south was all there was of the City, a very little town indeed, with crooked streets and low houses, now so transformed that scarcely a trace of them remains.”

But there are incredibly a few remnants still to be found over a century later, particularly if you look at the ground. Before landfill artificially expanded the island, the waterline used to come up to Pearl Street. Here Hemstreet records;

“Several bridges crossed the inlet, the largest at the point where Stone Street is. Through a pretty garden, Stone Street was reached. It was the first street to be laid with cobble stones, in 1657, and so came by its name.”

Today Stone Street is one of Manhattan’s oldest surviving streets and its curving path is still paved with cobblestones. Somewhat hidden away, Stone Street is lined with taverns and outdoor tables fill the streets. At the weekends it is, like much of the Financial District, peaceful. But when the offices empty out at lunchtimes and happy hour, it is one of the cities most bustling drinking spots. Rows of flags stream between the centuries old, low buildings, and it is as vibrant as when the merchants of the Dutch East India Company raised their tankards here centuries ago.

Just behind Stone Street is another Lower Manhattan treasure: South William Street. Its curves run parallel to Stone Street and its architecture is quite marvellous. Here you’ll find stepped gables, timbered facades and leaded windows that could easily grace the buildings overlooking the canals of Amsterdam. Rebuilt after the great fire of 1835 that destroyed much of Lower Manhattan, wander along South William Street to enjoy old world charm with a distinctive Flemish flair.

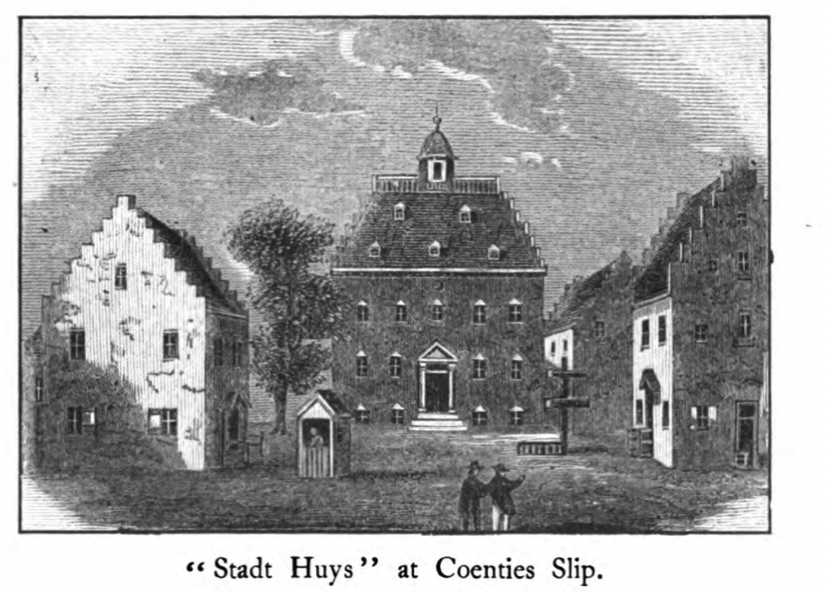

Whilst urban development steadily destroyed virtually all of New Amsterdam, it also unearthed a hidden gem. Take a look at the Google Map of the Financial District and just by the Pain Quotidian on Pearl Street opposite Coenties Slip, you’ll spot the mysterious sounding “Portal Down to Old New York”. When Charles Hemstreet stood here in 1899 he noted that sadly lost on this spot, was “the old first City Hall, built in 1642. There was a court room and a prison in the building. Outside, a cage and a public whipping post.”

But in 1975, building work uncovered the only physical remnants of the first Dutch settlement, the original foundations of the City Hall, or Stadt Huys, as well as the superb foundations of a tavern from the 1670s and an ancient well. Aside from the buildings, this first large scale archaeological excavation undertaken in Manhattan also yielded clay tobacco pipes, more than 11,000 pieces of glass, and 23,000 fragments of pottery. Walk by today and the site is perfectly preserved under glass set into the pavement Hemstreet walked over with little idea of the treasure lying below.

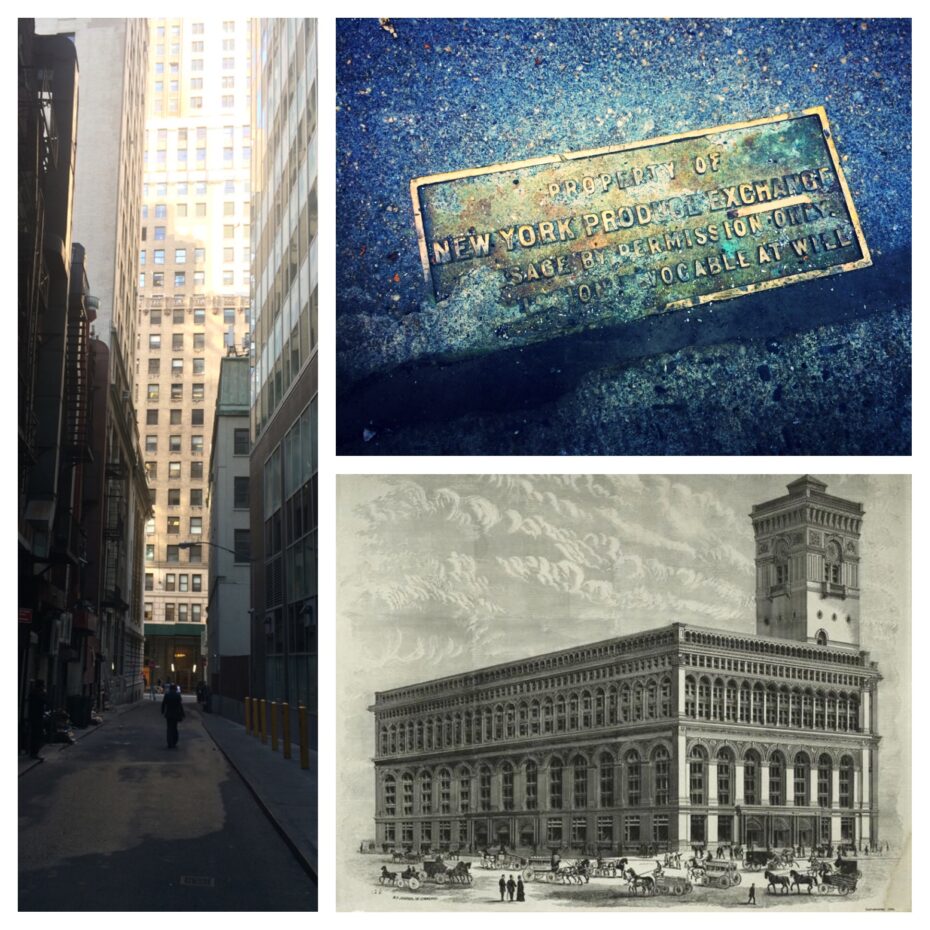

Other buildings were not so fortunate. Follow Broad Street northwards and you could easily miss Marketfield Street. Today it is a tiny L-shaped narrow and grimy alleyway, bereft of all foot traffic. It is as Hemstreet found out, “one of the great lost thoroughfares of the city. Almost as old as the city itself, it was then called Petticoat Lane.” During the days of New Amsterdam this filthy alley had been used to lead cattle to market at what is now Battery Park. When Hemstreet was writing, this rural idyll had been replaced fifteen years before with the Produce Exchange.

One of Manhattan’s great lost buildings, the Exchange was a colossal Beaux Arts masterpiece of red brick with Florentine details. One of the first buildings in Manhattan to offer elevators, it featured a vast skylight looking down on a stock exchange floor trading in wheat and oil to the tune of over $15 million a day. The New York Times described this beauty as, “the most impressive exchange structure ever seen in Manhattan”, yet it was criminally torn down in the 1950s to make way for a featureless office block. All that remains today is a tiny property marker set into the pavement of this forgotten alley that reads, “Property of New York Produce Exchange – Passage By Permission Only.” In his book Lost New York, Nathan Silver neatly sums up yet another architectural tragedy, “the Produce Exchange, one of the best buildings in New York was replaced in 1957 by one its worst.”

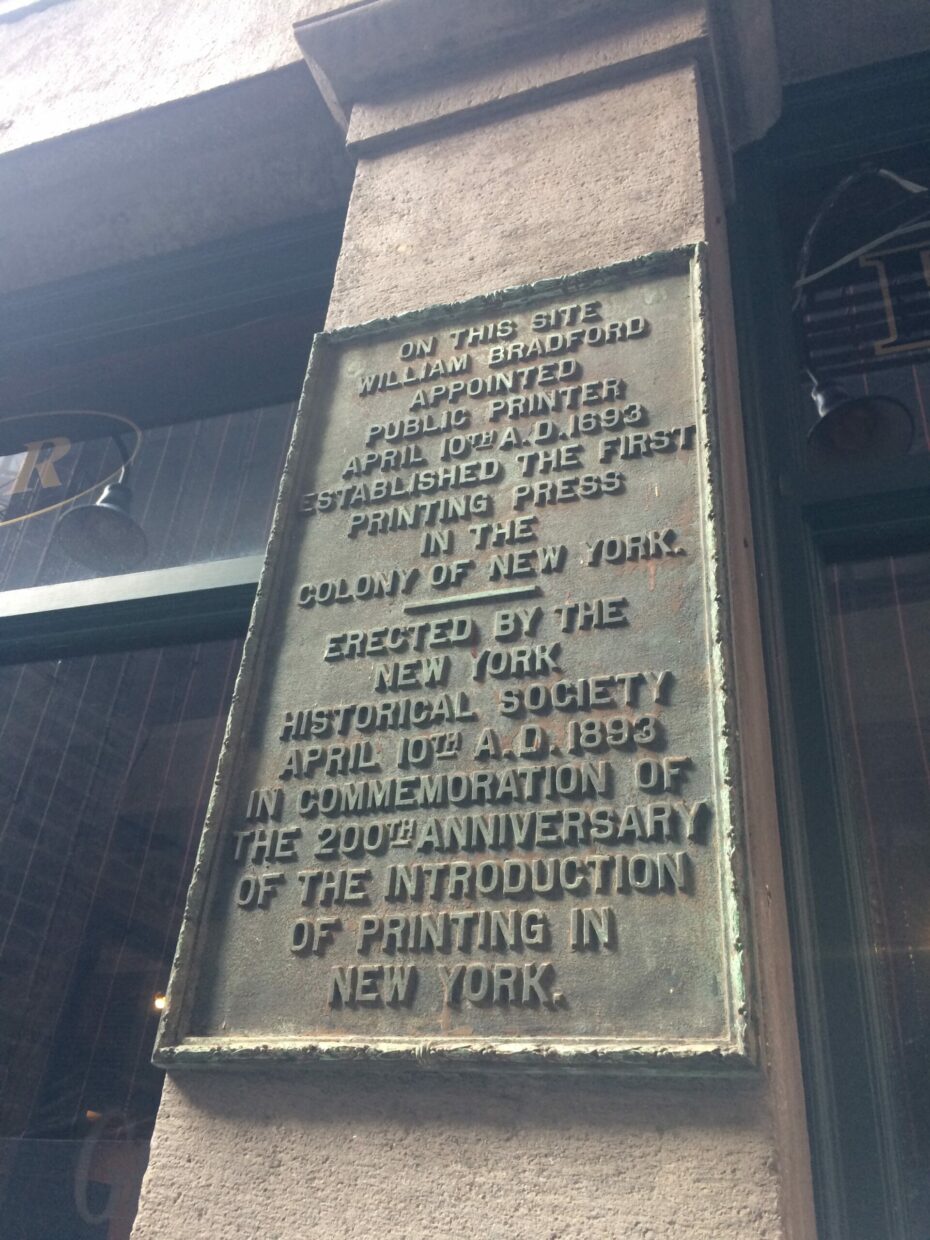

Whenever exploring a city, we always make sure to stop and read any historical plaque we come across. Usually passed by unread by most people, plaques will often tell you about some forgotten episode of history that once happened here, or perhaps it is all the remains of a place long torn down. Hemstreet was the same. He would hand draw maps showing wherever he found an old historic plaque in Lower Manhattan, indicating a long lost church, theatre or a place in history.

In ‘When Old New York Was Young’, he tells of a charming encounter with an older gentleman, himself obsessed with tracking down historical plaques.

“On a day in early summer I met a very old man standing where Broadway begins, and there was something so kindly in his manner that I ventured to stop and see why he gazed so long at a slab of bronze fastened to the wall of the house at No. 1 Broadway. It was a tablet placed there by one of the patriotic societies to mark the place on Bowling Green where the statue of King George III had stood in Revolutionary days. There must have been something sympathetic in my manner, for the old gentleman beamed as I stood beside him and read the inscribed words. “You too, study the tablets, I see” said he. “It is one of the best ways really to understand history. Books seem dry when we can visit the real scenes, and by reminders like this,” pointing with his cane, “recall what has happened on the self-same spot.” When I hinted that I was interested in all that had an old-time flavour, he told me he was seeking out the city’s tablet, and would be glad to have me accompany him. And so I did.”

Whilst some of the plaques Hemstreet catalogued have long since disappeared; such as a plaque near Gold Street named after Golden Hill, where the first blood of the American Revolution was spilt in January, 1770 in the back garden of a tavern between British soldiers and the ‘Liberty Boys’, many have survived today, such as one plaque outside one of the Stone Street saloons, placed in 1893 on the spot where the first printing press in New York was established in 1693.

Hemstreet picks up the tale of his plaque loving companion with advice that any modern day urban explorer would be wise to follow:

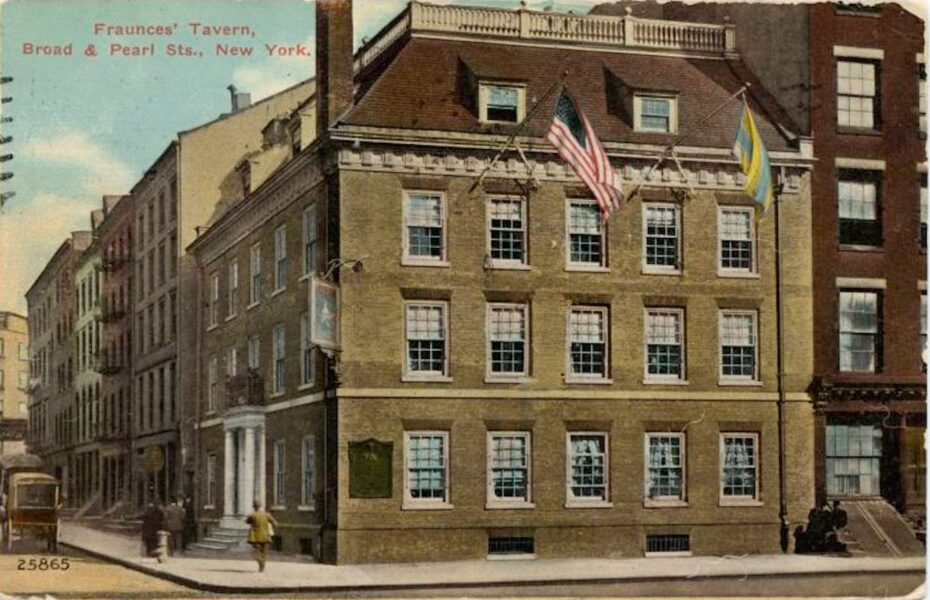

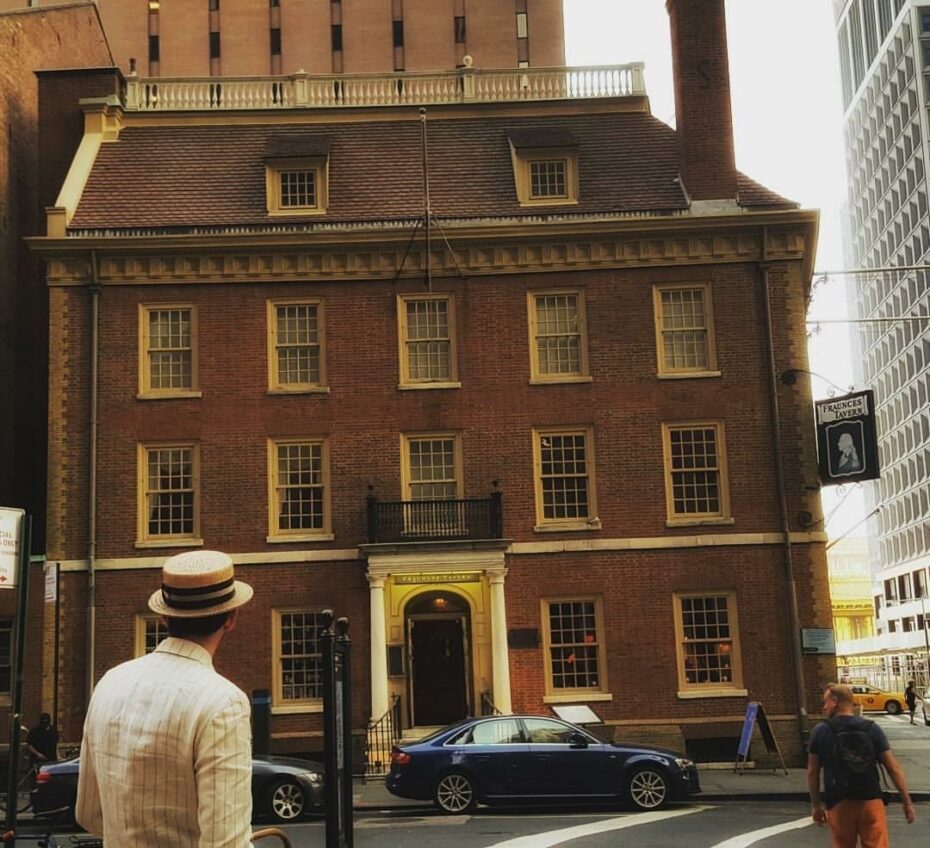

“Before we start,” said he, “let me tell you how I study. Forget the lofty buildings that rise above me, the modern vehicles, and the rush of busy life. I try to imagine what the town was like at the time of which this tablet tells….when we pass two streets farther on, you will see a landmark that should make your blood tingle. There it is, that square building on the corner, a little disfigured, with small windows that proclaim it of another decade. That is Fraunces Tavern…where Washington had his head-quarters and bade his officers farewell when the Revolution was at an end. You can see the tablet near the Pearl Street entrance. What fine tales these old walls could tell!” Saying this, he wished me good-day, with a courteous bow. I left him looking steadfastly southward, dreaming of the past, and doubtless passing in review a host of shadows that only he could see.”

The same plaque can still be seen outside venerable Fraunces Tavern. Step inside and you will find a warren of wooden passageways leading to bar rooms, Colonial-era style dining rooms and even a museum, commemorating the evening of December 4th, 1783, when just nine days after the last British troops had left American soil, George Washington bid his officers an emotional farewell.

Our particular favourite corner of Fraunces Tavern is the Dingle Whiskey Bar. Snug wooden pews face the bar, whilst comfortable easy chairs are drawn around the roaring fireplace to warm you along with a choice of over five hundred rare whiskies: it is all to easy to picture the Sons of Liberty ensconced in the corner, plotting against the Redcoats over their hot ale flips and planter’s punches.

After a warming wassail or a modern equivalent in the Tavern, head up Broad Street to reach simply one of the most famous street names in the world: Wall Street. But whilst it might be synonymous with American capitalist might, its name came quite naturally, for there was once an actual wall here, built to protect the villagers of New Amsterdam from the wilderness beyond.

As Hemstreet explains, “When war broke out between England and Holland in 1653, Governor Peter Stuyvesant built the wall along the line of the present street, from river to river. His object was to form a barrier that should enclose the city. It was a wall of wood, twelve feet high, with a slopping breastwork inside.” The stockade was torn down in 1699, but the former northern border of the city can still be pictured: glance down and you’ll see every few yards, small squares of wood set into the concrete, a reminder of the old palisade itself.

One of the best places to find visible remains of old New Amsterdam is in its former burial grounds. Where Wall Street meets Broadway, you’ll find Trinity Church and its graveyard that was built on a former Dutch farm. Its oldest gravestone is of a child, Richard Churcher who died on April 5th, 1681, aged just five years and five months.

Two of Hemstreet’s favourite tombstones which he noted in his book are ours as well: a few stones along from Richard Churcher is a grave belonging to a merchant and former officer in the British Army, who wrote his own jaunty epigraph which he himself placed on his tombstone, Sydney Breese:

Ha, Sydney, Sydney!

Lyest Thou Here?

I Here Lye,

’Til Time is Flown to

Its Extremity.

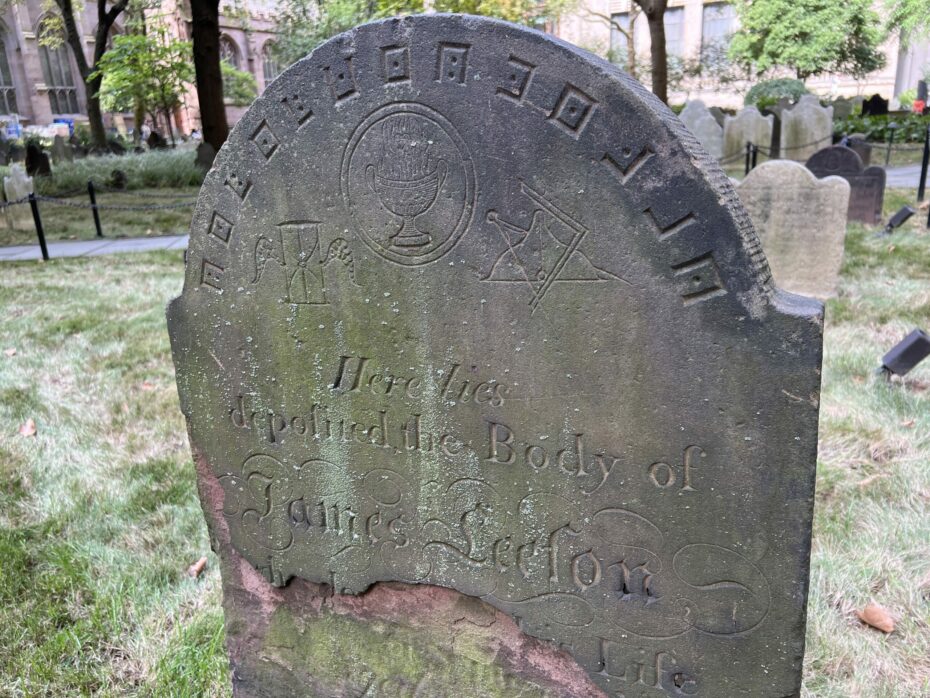

Hemstreet tells us where to find his other favourite; “close to the Martyrs’ Monument is a stone so near the fence that its inscription can be read from Broadway…..and above the inscription are cut these curious characters.” This is the peculiar gravestone of James Lesson, who left a coded message as his epitaph in 1794. For those who would like to know the secret behind the cipher, here’s the key!

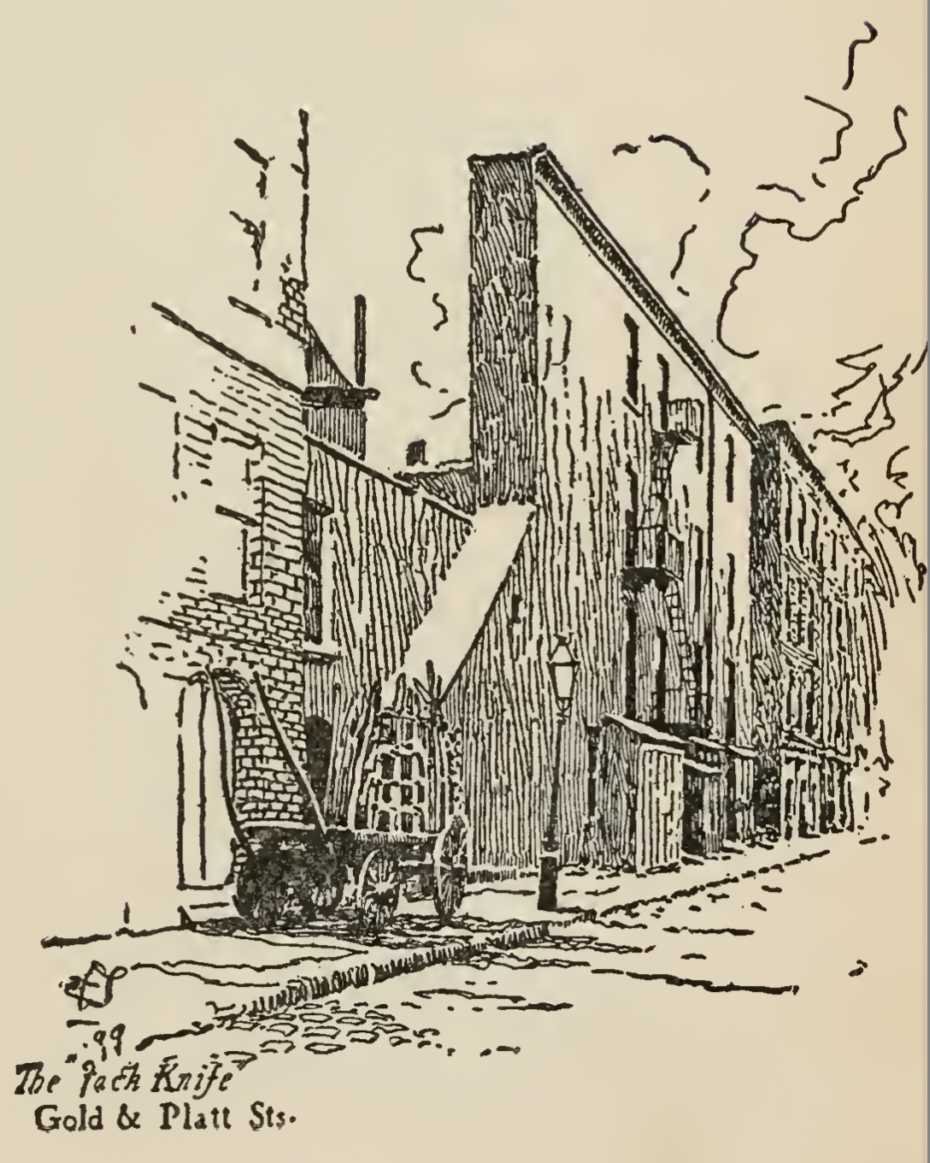

Whilst Trinity Church has survived, many of the treasures of old New York Hemstreet tracked down have sadly been lost, torn down and replaced with concrete and steel. Stand on the corner of Gold and Platt Street and a hundred years ago instead of skyscrapers you would have seen a peculiar shaped house in the shape of narrow wedge that went by the name of the ‘Jack Knife’.

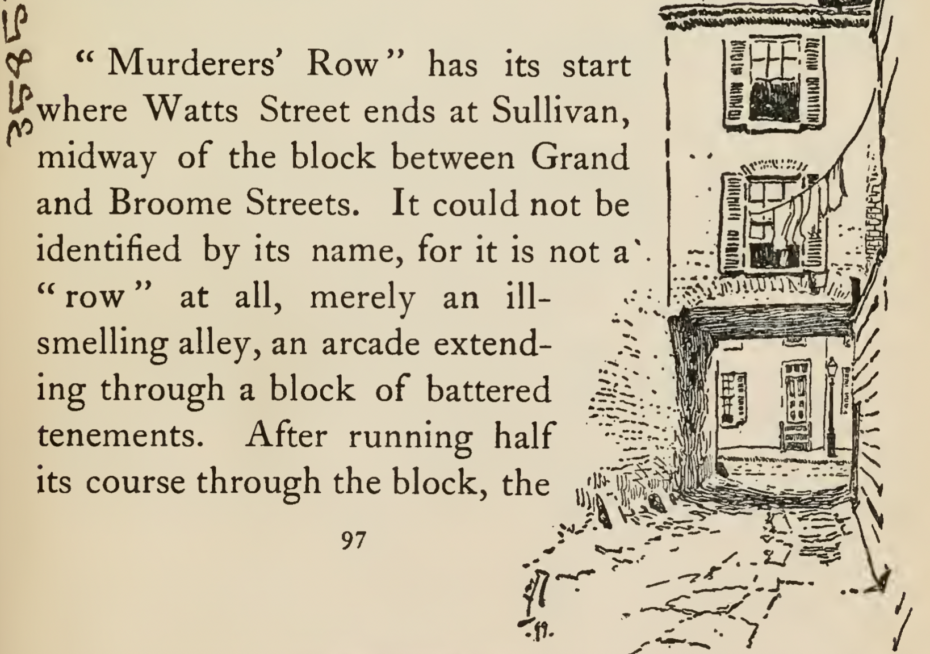

Also long lost are places like the tantalisingly named ‘Bone Alley’, ‘A House of Other Days’, ‘the Tombs’, and the ‘Gates of the Old House of Refuge’. Today, where Watts Street meets Sullivan Street, you’ll find anonymous looking office buildings; when Hemstreet stood here in 1899 it was known as the far more menacing, ‘“Murderers’ Row”. He records,

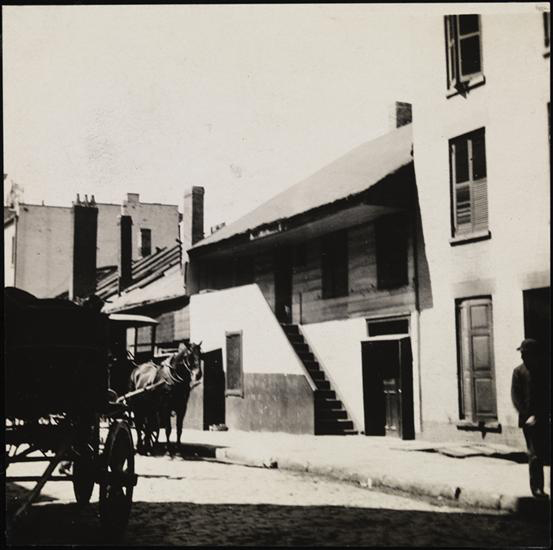

“It could not be identified by its name, for it is not a ‘row’ at all, merely an ill-smelling alley, an arcade extending through a block of battered tenements…..a space between houses, a space that is taken up by push carts, barrels, tumble-down wooden balconies and lines of drying clothes. “Murderers’ Row” is celebrated in police annals as a crime centre….constant complaints are made that the houses are hovels and the alley a breeding-place for disease.”

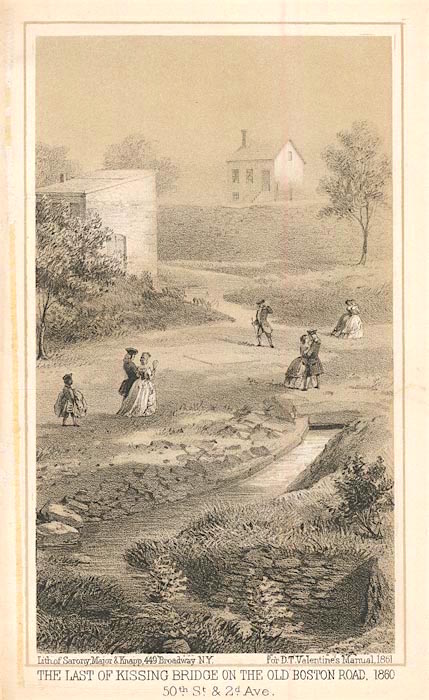

Whilst not many New Yorker’s would miss Murderers’ Row, it would be nice if the old Kissing Bridge were still there. This was a small bridge over a creek close by present day Chatham Square. Hemstreet noted that here,

“Travellers who left the city by this road parted with their friends on this bridge, it being the custom to accompany the traveler thus far from the city on his way.”

But other off the beaten path curios remain. Visit illustrious City Hall park and you’ll find four marble pillars at the southern entrance. Four granite balls, said to have been dug from the ruins of Troy.

The northeast corner of 13th Street and Third Avenue, had been until 1867 home to one of New York’s oldest living relics: a pear tree planted by Peter Stuyvesant, that he brought over from the Netherlands as a sapling and planted here in 1647. This fantastic living piece of history met an untimely demise when two wagons collided into it, but today outside the branch of Kiehl’s you can still find a replanted tree and a plaque commemorating the wonderful story of Peter Stuyvesant’s pear tree.

We leave Charles Hemstreet’s adventures with the discovery of something remarkable; something that if we hadn’t come across a copy of his book one in evening in our local tavern, we’d never have known about. We’ve spent over a decade exploring every corner of Manhattan, with much of it appearing here in our book, Don’t Be A Tourist In New York. But one of the never ending charms of the New York City is that just when you think there is nothing new to discover, something incredible turns up. Here it is, courtesy of a book written over 130 years ago.

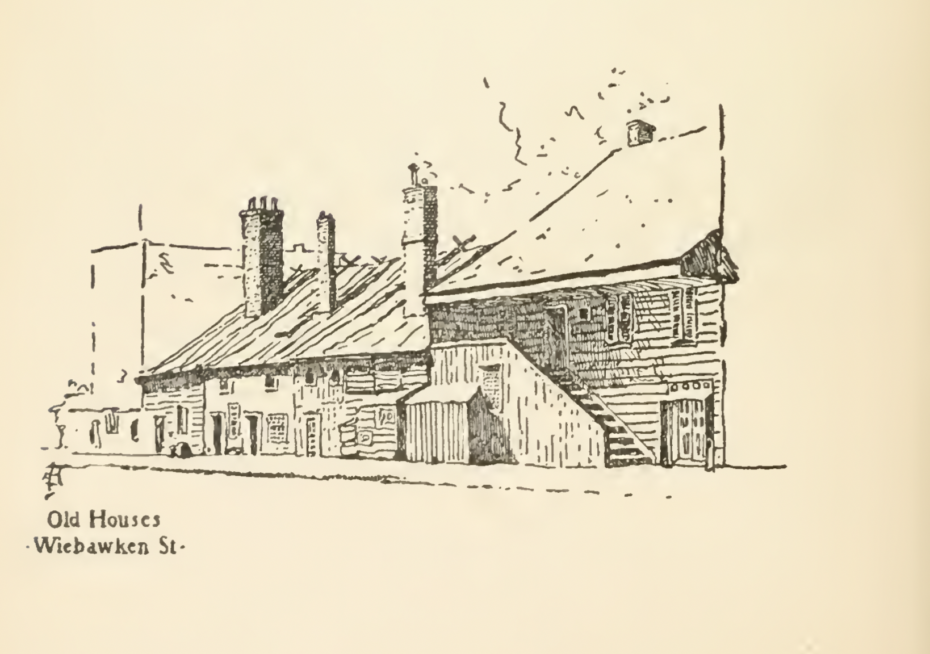

Weekawken Street is one of those small Manhattan streets so tiny as to be forgotten. Hidden away on the far west side, it is home to just a handful of buildings. This was formerly the site of the Newgate State Prison in the early part of the 19th century, and a marketplace. As Hemstreet explains, “although the prison has been swept away, an idea of its locality can be had from the low buildings at the west side of nearby Weehawken Street. These buildings have stood for more than a hundred years, having been erected before the prison.”

Today incredibly one vestige still remains, a tiny wooden house centuries old. Nowhere as near as famous as New York’s other historical wooden homes, such as the Lefferts Historic House in Brooklyn (1783), or the Edgar Allan Poe cottage in the Bronx (1797), this small wooden house is all but forgotten, much as it was when Hemstreet came here in 1899. One likes to imagine our kindred spirit in urban exploration standing here amidst the din of the new steamships docking at the West side piers, the ever increasing urban sprawl and marvelling that something so small and ancient could possibly have survived. Over a hundred and thirty years later, we can stand in the same spot and marvel still at a true relic of when Old New York was indeed still young.