The largest collection of Moorish Revival architecture in America and the Western Hemisphere is where you’d least (or maybe most) expect it: Florida. A development project before it’s time, from the vision of 1920s aviation and motorcycling pioneer who was inspired by One Thousand and One Nights, Opa-locka in Miami-Dade County has street names like Sharazad Boulevard, Sinbad Avenue, and Sultan Avenue and over a hundred buildings with a unique blend of Arabic, Persian and Moorish themes. The cherry on the cake is probably the historical City Hall building, featuring an onion dome and minarets, inspired by the description of Emperor Kosroushah’s palace in A Thousand and One Nights, but the entire building is abandoned today. We had questions, so join us for a quick tour.

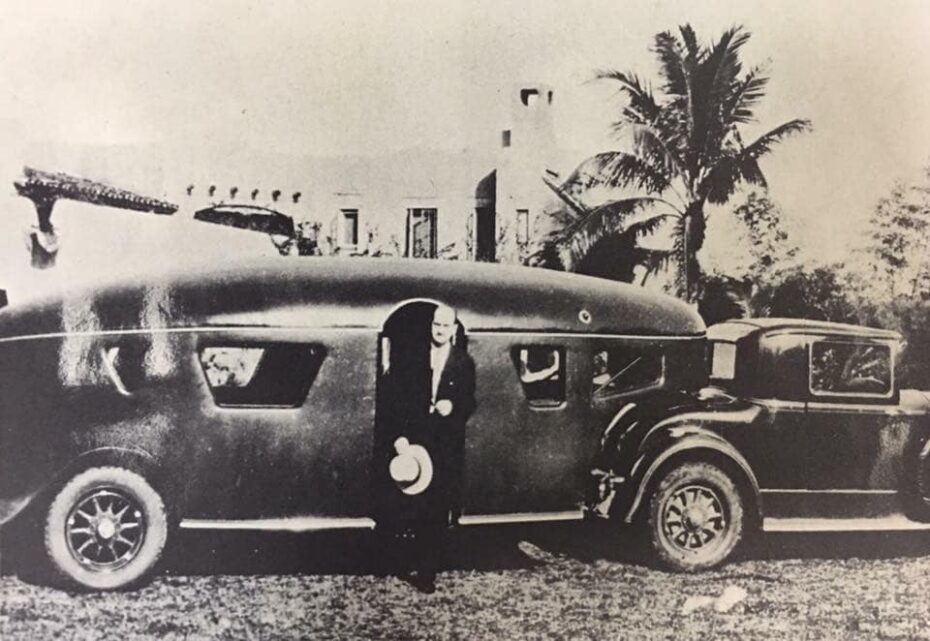

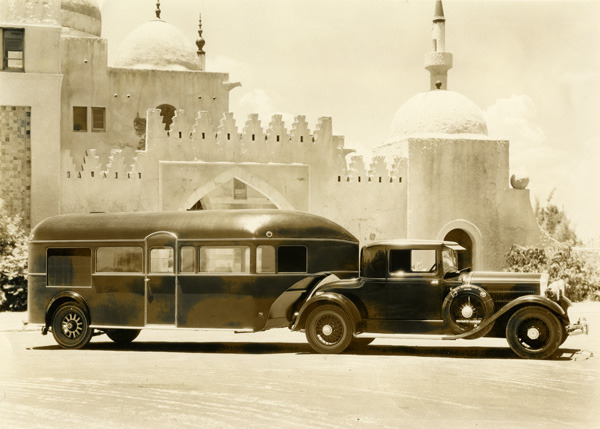

The name Opa-locka comes from a shortened version of the Seminole place name Opa-tisha-wocka-locka, meaning “a big island covered with many trees and swamps.” Multimillionaire Glenn Curtiss was behind the 1920s construction of the city and chose to distinguish it from other competing new communities with a theme that would get folks talking. Having already been a leader in the nascent aviation industry, he also co-founded the cities of Miami Springs and Hialeah. He was invariably known as the Fastest Man on Earth and the Father of the Aviation Industry, a title he battled with the Wright brothers over. In 1927, he invented the streamlined Aero-Car trailer and had them manufactured in Opa-Locka.

The development was part of that decade’s Florida land boom, the southern state’s first real estate bubble during which many communities were built with specific themes, largely in a style that would come to be known as Mediterranean Revival. Miami Shores, for example, was done in an Italian style with a Venetian style canal up one of the main thoroughfares, complete with gondolas. While Palm Beach and Coral Springs took on a Spanish style.

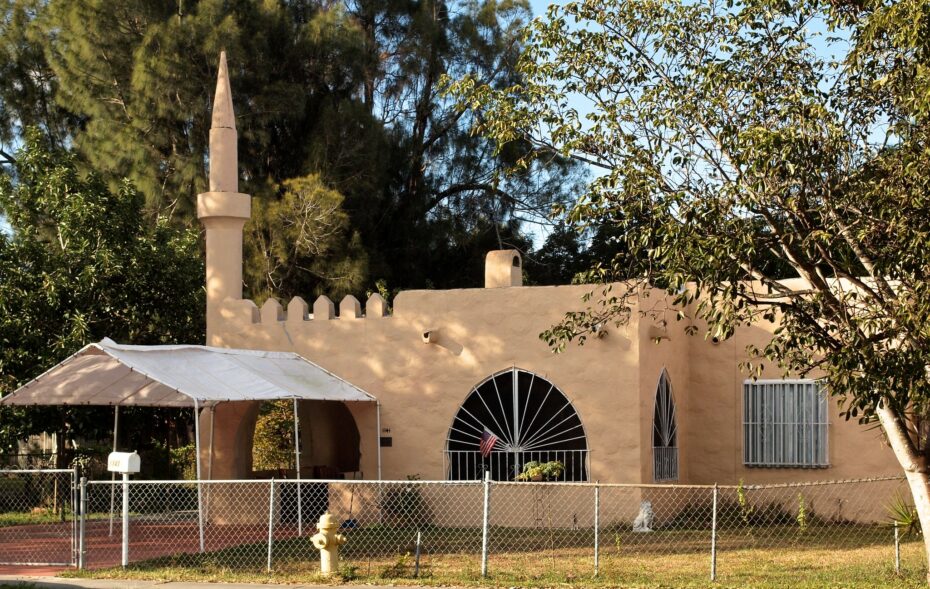

But amidst this development rush, Opa-locka stood out for its uniqueness. Curtiss worked with architect Bernhardt Muller (who had already developed a unique Robin Hood-style on previous projects mixing medieval, Tutor and Elizabethan periods) on the construction of 105 buildings, featuring architectural elements straight out of another era: domes, minarets and outside staircases. The self-contained city included an airport, archery club, golf course, hotel, train station and a zoo. The City Hall began as the developer’s main administration building and a showcase for buyers. Its candy coloured decorations, balconies, domes and minarets are fantasy architecture at its best. It was in service until 2009, when the municipal offices moved a few blocks away. Still awaiting renovation, you can’t enter the building which is in very poor shape but the walled garden is still worth seeing.

On the corner of Opa-locka Blvd and Ali Baba Blvd, The Hurt Building was the old hotel and just across Ali Baba is the restored railroad station; neither are open to the public today. The home Curtiss had built for himself and his wife Lena was called Dar Err Aha, a Persian phrase meaning “house of contentment”, and is available to hire for events.

In his 1987 book Miami: City of the Future, T.D. Allman described Opa-Locka it as “the wackiest Miami real estate scheme of all time.”

In the nonfiction book A Dream of Araby: Glen H. Curtiss and the Founding of Opa-Locka, local resident Frank S. FitzGerald-Bush recalls the history of the town in great deal, including his parents’ friendship with Curtiss. He recalled the many characters who passed through the town, like a Russian baroness and opera singer who had escaped the Bolsheviks and sang in the local church.

He described the town as starting from nothing to “buildings rising as if by magic,” quickly becoming a hotspot for “all the great and near-great who visited south Florida.”

“Strange as it may now appear, in that brief but wonderful period of 1926 to 1928, coming to Opa-locka was considered to be very chic. Everyone, from socialite to ordinary tourist, made at least one trip to what one may appropriately say had become a mecca for Miamians.”

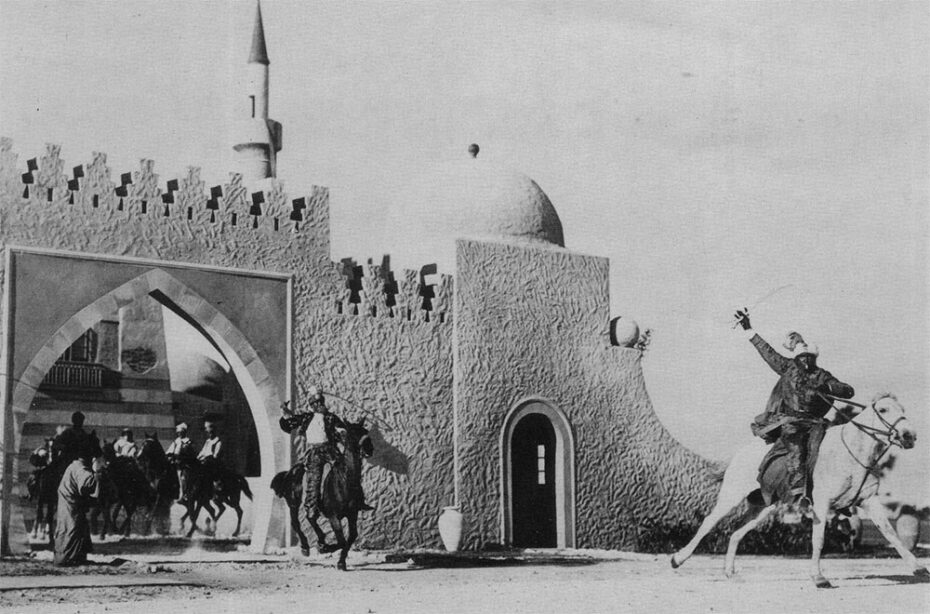

Great fanfare marked major events, like the Arabian Fantasy Nights celebrating the opening of the Orange Blossom Special railroad connecting New York and Miami (featuring people wandering through the streets in theme-appropriate costumes rented from New York theaters).

But tragedy struck just a few years later, when the 1926 Miami hurricane swept through the area, while the damage to Opa-Locka was relatively minor, it ended up marking the end of Florida’s land boom. An economic depression ahead of the 1929 crash was already starting to hit the region.

Still, Curtiss kept building the rest of the planned works and paid for their maintenance. He always dreamed of continuing development when financial conditions improved but he passed away in 1930. For architect Muller, he never realized his dream of a city featuring Egyptian and Chinese sections, as well as an English village.

Still, many of Opa-locka’s structures have survived and no less than 20 of the Moorish Revival buildings are part of the National Register of Historic Places. These include the white and pink Opa-Locka old City Hall and the Seaboard Air Line Railroad Station as well as individual homes like the Baird House and the Crouse House (which originally featured a dome and bell tower). Given its unique architecture, the city has also been the backdrop for many films including Salesman, Bad Boys II and 2 Fast 2 Furious.

And one of Curtiss’s final acts — giving the United States Navy the small airfield of his Florida Aviation Camp — would give the city a new importance in the coming years. Amelia Earheart launched her fateful trip around the world from a nearby airport, but it was in 1953 and ‘54 that a two-story barracks in the Opa-locka Airport became the headquarters for PBSuccess, a large-scale CIA operation to overthrow the leftist Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz. (Interestingly enough, one of the operatives working on PBSuccess was E. Howard Hunt, who went on to be one of the masterminds behind the Watergate scandal). The success of the US-led coup partially sparked the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, with the Opa-locka airfield serving as a listening post for Cuba. The base also sheltered children during the 1960-1962 Operation Pedro Pan airlift and the 1980 Mariel boatlift.

Over the years, the demographics of Opa-locka also changed drastically, going from majority white to majority African American. Within Dade County, it was a hotbed for Black empowerment during the Civl Rights movement. It was even the first US community to honor the country’s first Black president when a mile-long street was renamed Barack Obama Avenue on February 17, 2009.

Still, the city has also faced decades of financial instability as well as gang violence and drugs. Many of the Arabian structures are currently closed down and in a state of disrepair. The original vision of Opa-locka might seem more like a mirage than ever. But there’s always the hope that its short glory years could be revived. Even back in the 1970s, while exploring the city he could barely remember from his early childhood, author Franks S. FitzGerald-Bush reflected on a sort of tropical Atlantis that seemed to only exist in dreams. Or, more appropriately, in a fable.

“If the little city lacked great prosperity, it had great beauty and peace. Talking to those who grew up in Opa-locka during that decade I find myself envying the privilege given them but denied me. But for me, as for Opa-locka, it is futile to speculate on what might have been. We can never know the joys — or the perils — of the road not taken.”