Daily life could be grim in early modern London. Plague and other diseases seemed to lurk in the shadows. Education was out of reach for most. And the contents–or lack thereof–of your dinner table relied almost entirely on forces of nature beyond your control and which were running amok in a period of global cooling known as the Little Ice Age.

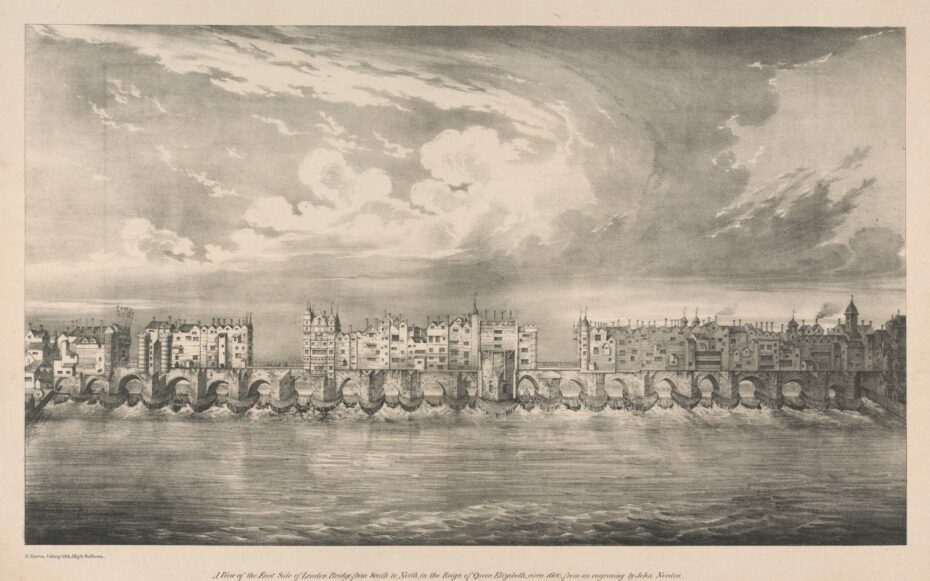

Flowing through it all was the mighty River Thames, lined with the pleasure palaces of the rich and powerful, shallow and fickle with its tidal comings and goings, yet absolutely essential to the English economy as the major transport hub for people and goods. London’s ferrymen kept both moving up, down and across the river because until 1750, the Thames had only one crossing within the city: old London Bridge, of nursery-rhyme fame. The famous line that sees the bridge “falling down” wasn’t just a fun excuse to entrap your classmate in a schoolyard game. Old London Bridge was lined on both sides with a haphazard collection of multi-story shops and houses in a time before building codes, safety measures or strict adherence to structural integrity. In 1608, those crumbling facades became the backdrop and, at least partially, the impetus behind one of London’s greatest parties and a tradition that would endure for more than 200 years.

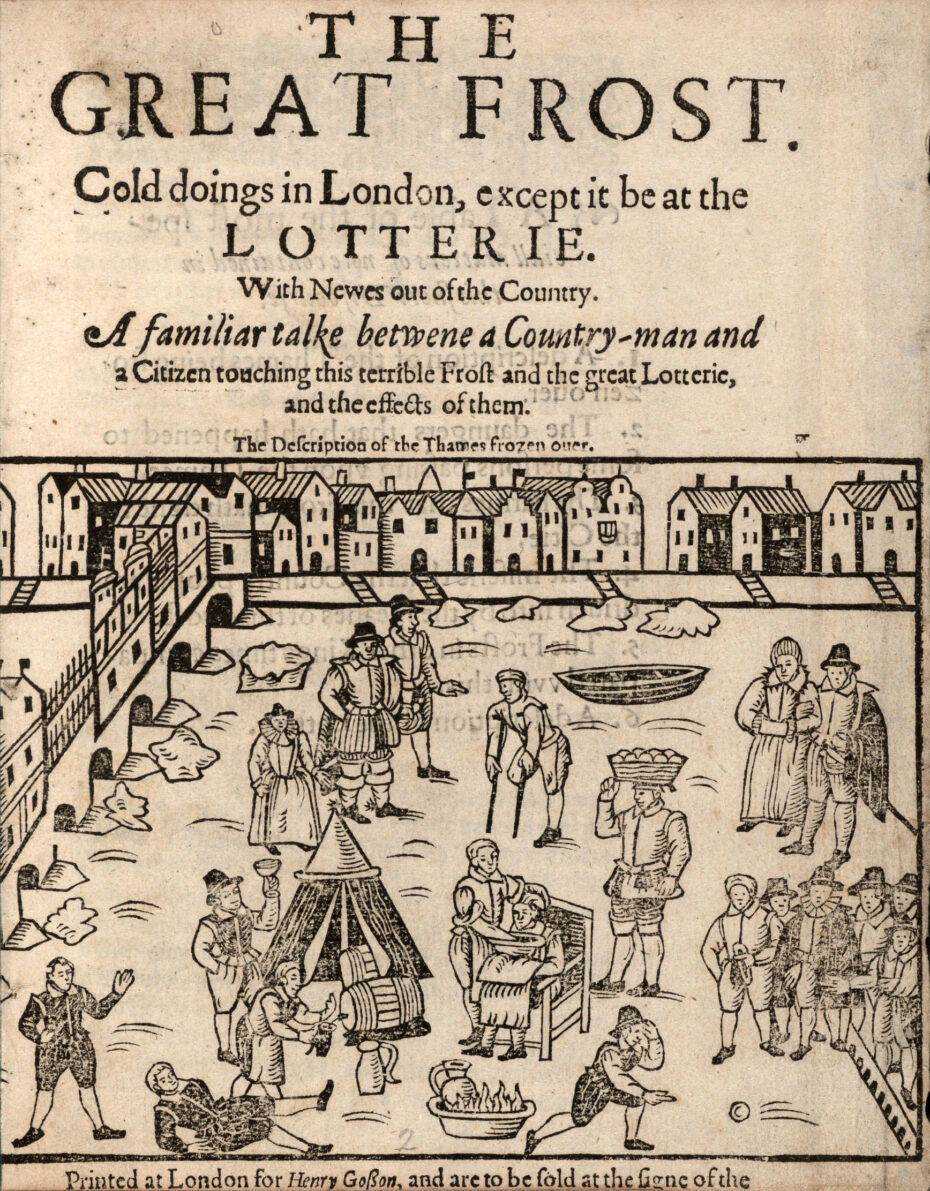

That winter, the detritus gathered by the Thames on its slow journey to the sea became tangled among the 19 narrow arches of London Bridge. As temperatures plummeted across England and ice formed in chunks on the river, those, too, were lodged against the bridge, forming a dam that eventually allowed the slow, shallow Thames to freeze solid. What ensued was a supply-chain nightmare. Crops and cattle froze in the fields up and down the country, making food supplies scarce. But with London’s main transport route at a complete standstill, even what little food could be found couldn’t be moved to where it was needed. Elizabethan pamphleteer Thomas Dekker described the despair of the city’s shopkeepers and watermen:

“Shop-kéepers may sit and aske what doe you lacke, when the passengers may very well reply, what doe you lacke your selues: they may sit and stare on men, but not sit and sell: it was (before) called The dead Terme, and now may wee call this, The dead Vacation, The frozen Vacation, The cold Vacation. If it be a Gentlemans life to liue idlely, and doe nothing, how many poore Artificers and Trades-men haue béene made Gentlemen then by this Frost? For a number of Occupations (like the flakes of yce that lye in the Thames) are by this malice of Winter, trod cleane vnder foote, and will not yet bee able to stirre. Alas poore Watermen, you haue had cold chéere at this banquet: you that liue altogether vpon water, can now scarce get water to your hands: it is a hard thing now for you to earne your bread with the sweate of your browes.”

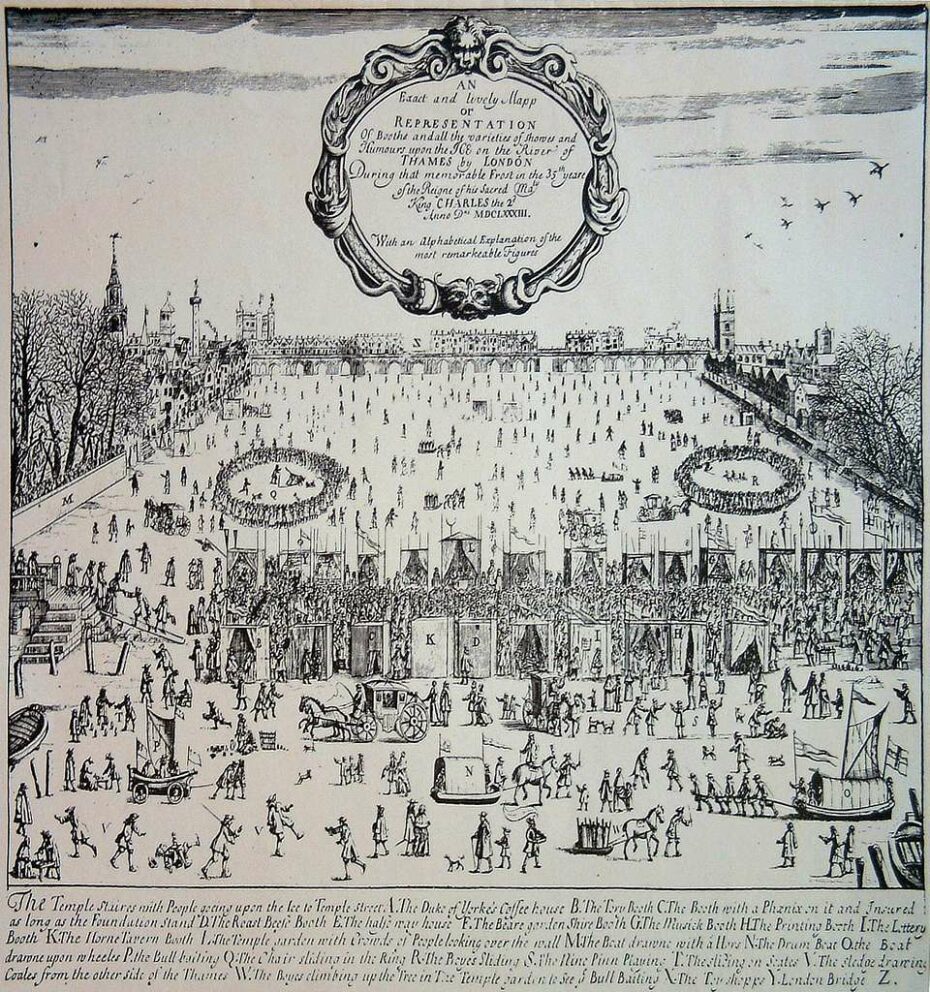

Out-of-work Londoners with little else to do crowded the icy banks to stare at this frozen novelty, with some brave souls daring to venture onto the ice. The bargemen of the Thames sensed a business opportunity: if they could transport people down a watery river in warm weather, why not guide them safely onto a solid one, for a small fee of course? The success of this icy tourist attraction inspired other merchants to join the festivities as well, and soon the ice was crowded with pop-up vendors. Beer and ale poured from temporary taverns, costermongers peddled fruit, fires blazed on the ice to keep revellers and shopkeepers warm, and diversions abounded. Nine-pin bowling and a marble game called “pigeon hole” offered entertainment, and if you found yourself in need of a shave while on the ice, two barbers plied their trade in the middle of the Thames. Dekker reported that many men who needed no shave nevertheless queued up for a trim “because another day they might report, that they lost their haire betweene the banke side and London.”

Frost Fairs were hedonism on full, frigid display because if there’s one thing humans can agree on across history and geography, it’s that when the world as you know it is ending, you may as well throw an outrageous party. The Great Frost of 1608 gripped London for six weeks, but the legacy of that terrible freeze sparked a tradition of frozen fun and frolic that spanned the next two centuries. Between 1608 and 1814, London hosted seven major Frost Fairs, each more elaborate than the last.

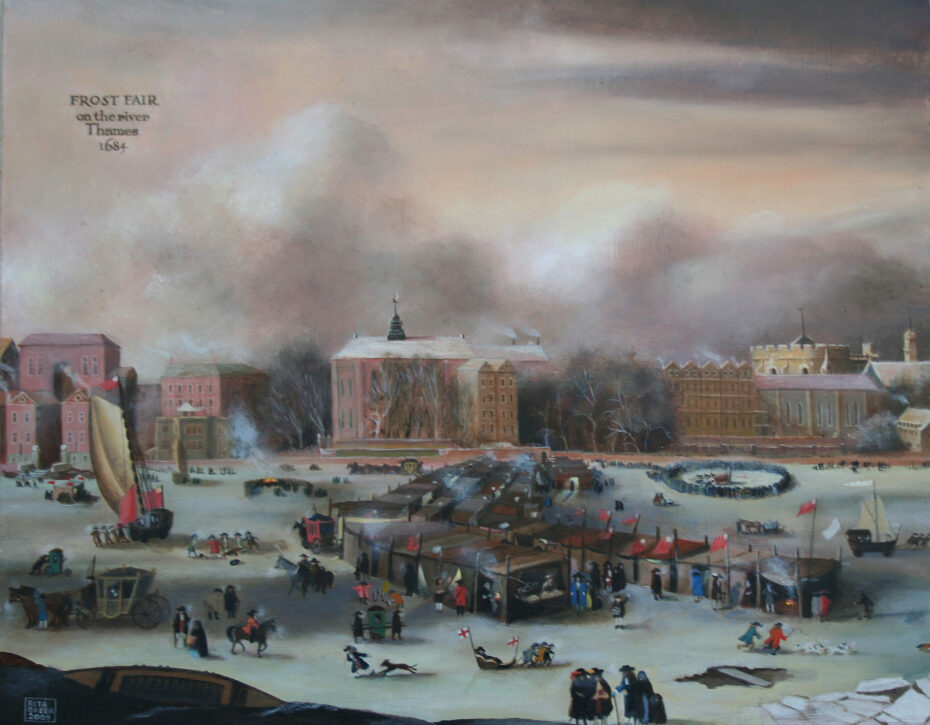

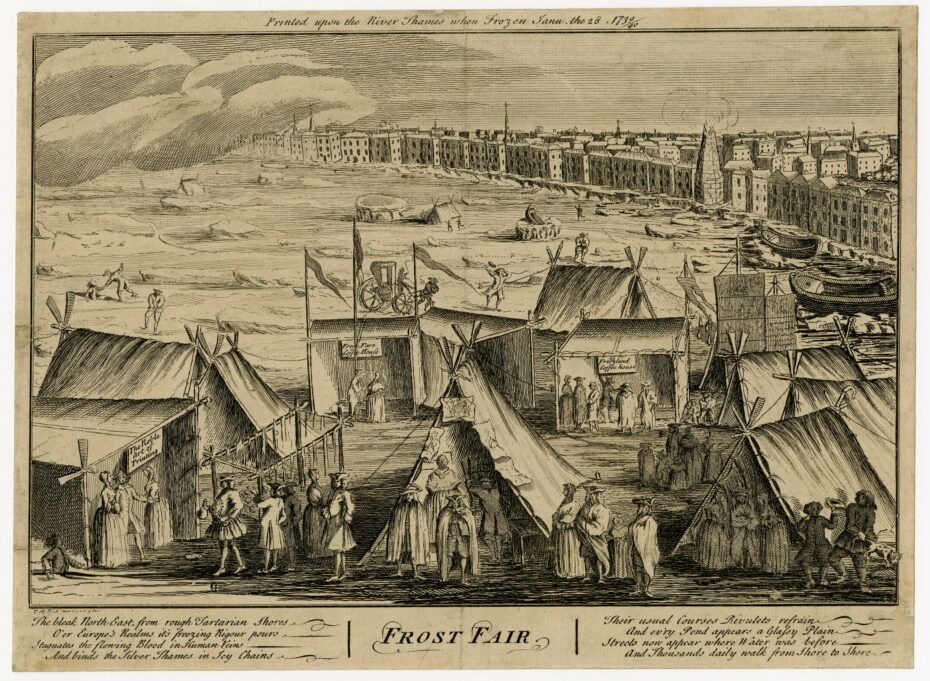

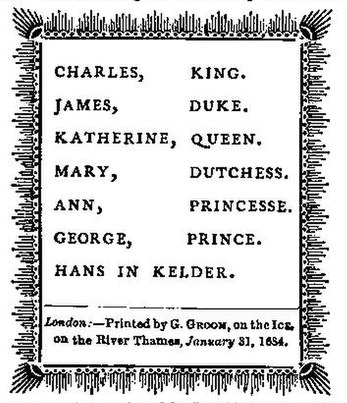

During the Great Winter of 1683-84, with the seas frozen up to two miles around the coast of England, printers set up their presses on the ice, selling tickets emblazoned with visitors’ names as a memento of their icebound merriment. Even Charles II and his court purchased tickets as they strolled among the frosty city of tents with the smell of spit-roasted ox hanging in the air and the shouts from the bull-baiting ring echoing up and down the frozen highway. Puppet shows, sleigh rides and coach races filled this river-turned-market-square, and “tipling and other lewd places” created “a bacchanalian triumph or carnival on the water” according to diarist John Evelyn.

Frost Fair traditions were passed down from one generation to the next, with the same butcher families recorded roasting the oxen despite decades elapsing between fairs. Printing presses became a staple at each subsequent fair, and pastimes considered cruel today such as bear baiting, “throwing at cocks” and fox hunts proliferated. For those seeking less bloody entertainments, menageries, music and dancing offered novel ways to spend a day in an icy wonderland.

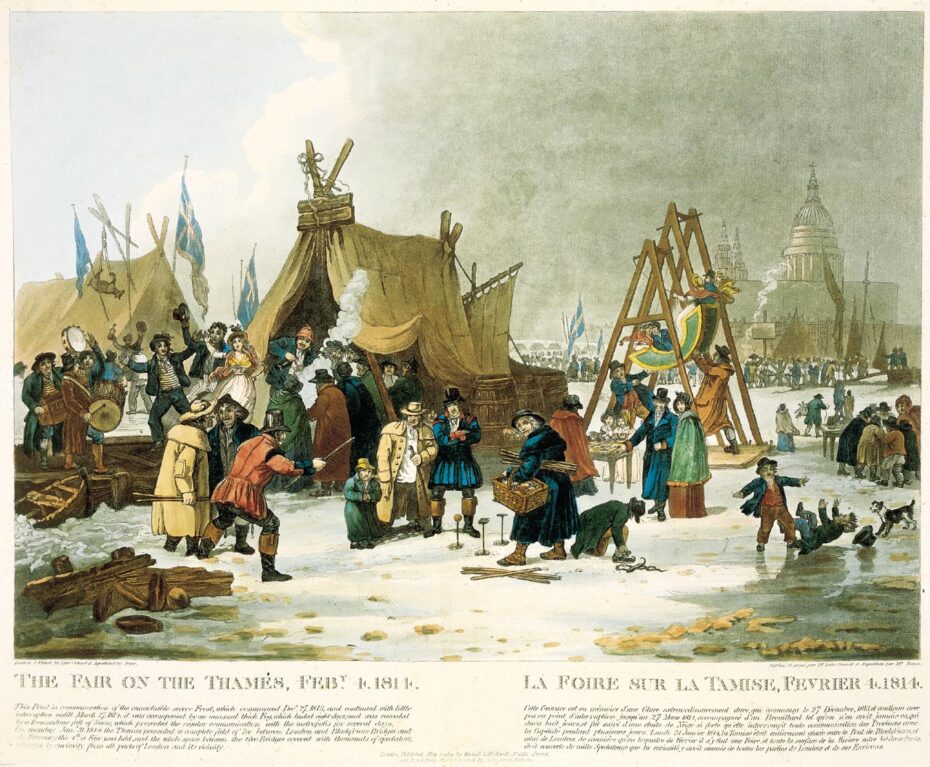

None of the merrymakers sipping gin and nibbling gingerbread while an elephant paraded across the frozen Thames in 1814 knew they would be the last to witness London’s greatest winter celebration. The five-day party was packed with “fuddling tents,” temporary pubs nicknamed after the state of utter confusion one might find oneself in after sampling the many potent gin-based beverages on offer. Mutton and mince pies, roast rabbit and warm apples, hot chocolate and steaming cups of tea kept bellies filled and spirits warm. But when the ice melted and drifted down river five days later, it took with it the last vestiges of London’s famed Frost Fairs.

Painting by Luke Clenell, via Wikimedia Commons.

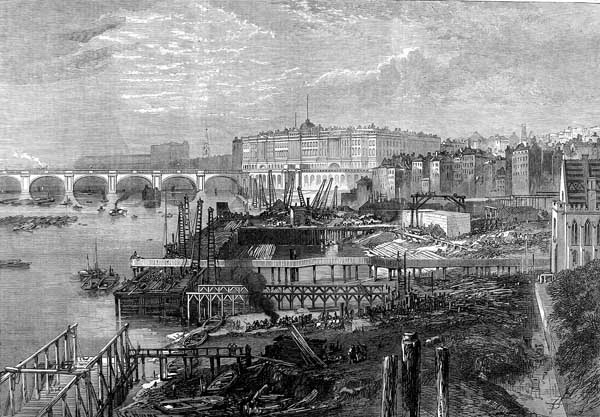

In 1831, the medieval London Bridge was demolished in favor of a more modern design. The new bridge featured only five arches, allowing water to flow faster underneath. This also meant more salt could flow upstream from the river’s mouth, raising the freezing point of the Thames.

The final blow to the great Frost Fairs came, a bit ironically, in the steaming summer of 1858. The introduction of flushing toilets to the city strained a crumbling sewer system, with waste being discharged directly into the Thames. Discharges from factories and slaughterhouses compounded the problem, and as London baked under a punishing sun, the river’s water level dropped, concentrating the noxious water into a stinking cesspit and exacerbating growing outbreaks of diseases such as cholera. The Great Stink permeated the city and prompted Parliament to act in order to rehabilitate London’s prime waterway. The newly formed Metropolitan Board of Works embarked on a massive infrastructure project to build a modern sewer system and embank the Thames, deepening the river and allowing it to flow more freely. While the project vastly improved London’s quality of life, it also made future Frost Fairs impossible. A deep, fast-flowing, brackish Thames situated in a warming climate will never freeze solid enough for such a raucous party again.

On the south bank of the Thames, under Southwark Bridge, a mural begs us to remember those lost days of frozen revelry.

Behold the Liquid Thames frozen o’re,

That lately Ships of mighty Burthen bore…

And lay it by that ages yet to come

May see what things upon the ice were done.