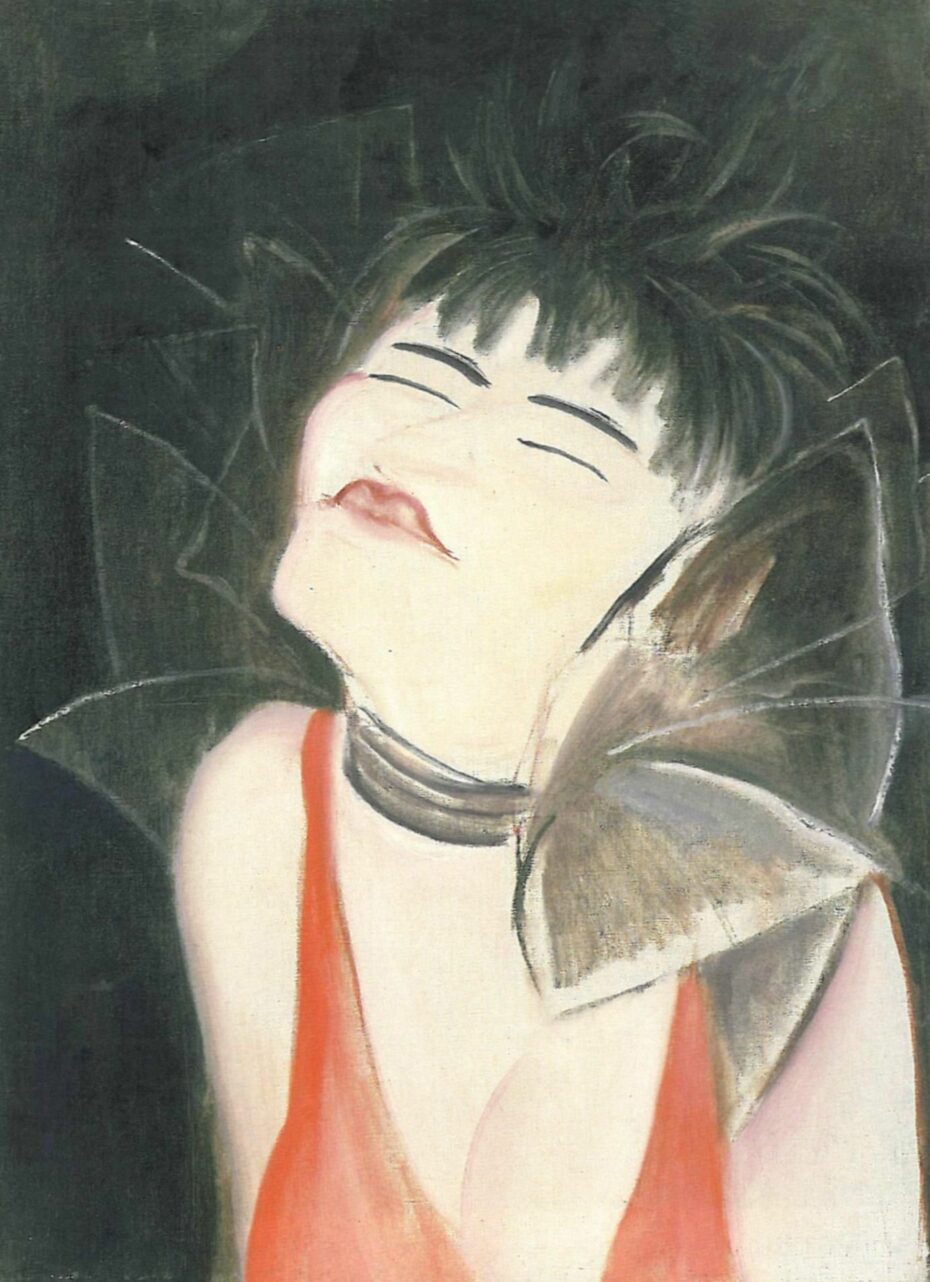

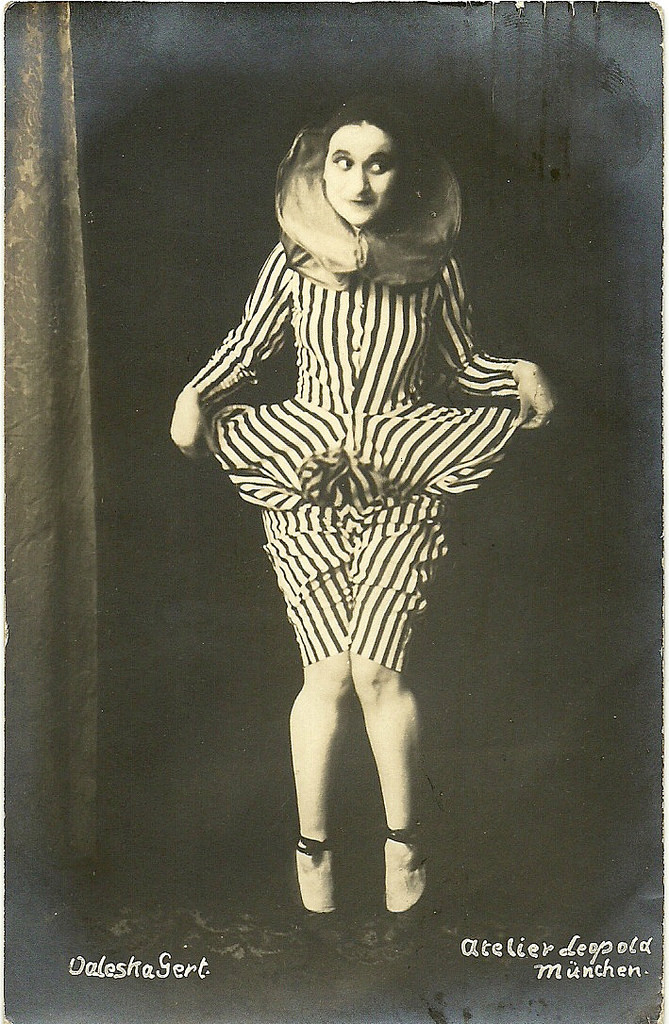

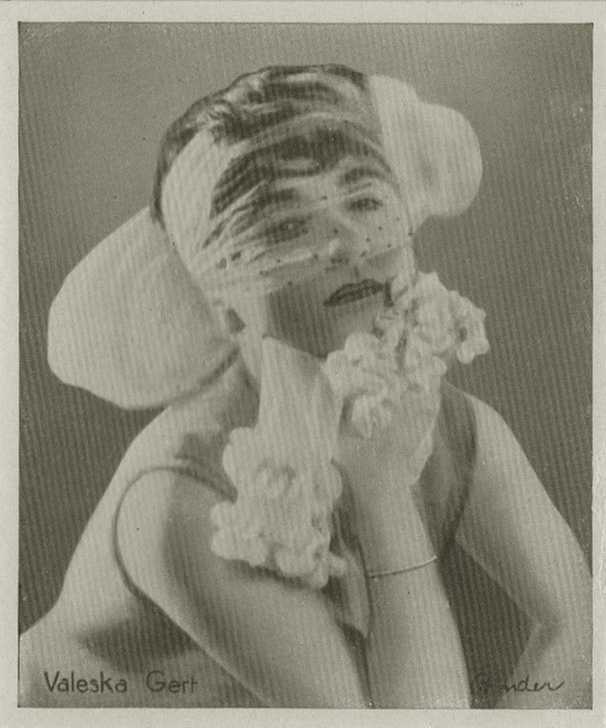

Thought punk was an invention of the 70s? Think again. A diminutive ravenette bombshell with animated eye-brows, brash blue eyeshadow, chalk-white skin and red lips was eons ahead of the curve and had laid the foundations of the punk movement w-a-y back in the 1920s already. Dance performance artist, cabaret queen, pantomimist, big & small screen actress, writer and sage (also nude model and dishwasher, inevitably), Valeska Gert’s non-conformist approach inspired creatives – from German Expressionism to the 70s/80s punk movement. She worked with legends like Federico Fellini, Bertolt Brecht and Greta Garbo and employed none other than Jackson Pollock and Tennessee Williams. ‘Lookalike’ fellow German provocateur and ‘godmother of punk’, Nina Hagen invariably springs to mind as a modern day comparison. Valeska Gert’s inexhaustible creative energy was a magnet to likeminded makers and shakers, and in a career that spanned 6 decades and various intercontinental hops, she embraced every avant-garde movement of the day, from Dadaism to Surrealism.

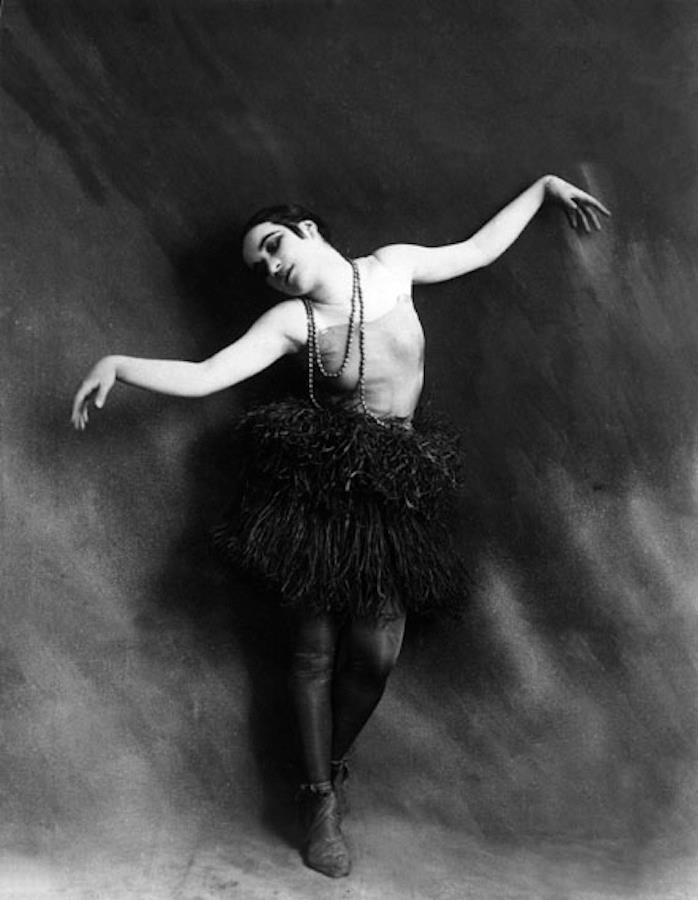

So ahead of her time and outright badass was Valeska Gert’s approach to performance art, that when she danced coitus onstage in the 1920s, a shell-shocked audience called the police. In a characteristically short impact performance piece, Der Tod (The Death), she performed her own death to a gob-smacked yet riveted audience. At other times she appeared on stage and … just stood still, in a dramatic attempt to draw attention to all the chaos around.

Valeska Gert was arguably one of the most memorable fringe artists of our time. She used the full repertoire of her body and her awkward presence to tell socially critical stories of life, birth, death, prostitution, orgasm, gender and stereotypes in a way unseen before, always remaining faithful to her own integrity and creative vision. She didn’t give a hoot whether audiences were uncomfortable, repelled, disgusted, baffled or appreciative, all that counted was the ‘story’. She had to be her own role model as none existed.

Audiences didn’t know how to categorise her, she was a phenomenon they’d never encountered before: an unstoppable renegade rebel: mesmerising, fearless, anarchic, radical and intense, showing a manicured finger to the establishment and to the niceties of convention. When in 1916, in what is generally considered her stage debut, Tanz in Orange (Dance in Orange), she defied the dance development of the era, Ausdruckstanz (Expressionist Dance), declaring it boring and bourgeois, saying, “I danced all of the people that the upright citizen despised: whores, pimps, depraved souls—the ones who slipped through the cracks.”

Gertrud Valesca Samosh was born on January 11th, 1892 to Jewish parents, her father a manufacturer of hat accessories. At age nine she already knew she was destined to dance and definitely not pursue academics, which launched her straight into the inevitability of performing for a living. During WW1 she had to count even more heavily on her own creativity to keep the wolf from the door as her father’s business suffered. She joined a Berlin dance group and started to develop what would become her characteristically provocative and satirical dance form. In one of her autobiographies, Mein Weg (My Way, 1931), she said,” I made myself a costume out of orange silk. … Full of bravado, I exploded like a bomb from the wings. And the same movements I’d danced soft and gracefully at the rehearsal I now exaggerated wildly. With giant steps I stormed straight across the podium, my arms swinging like a big pendulum, hands outspread, face contorted in a brazen grimace. … The dance was a spark in a powder keg. The audience exploded, yelled, whistled, hurrahed. I exited with a brash grin.”

In the 1920s she toured and performed all over Europe, at Bethold Brecht’s cabaret the Red Revue, in Germany, Paris, London and elsewhere: a tiny box of dynamite, a mini-caricature – mocking, shocking, alienating and hypnotising audiences in equal measure. She then started to focus on large screen acting, performing in films like Diary of a Lost Girl (1925), Joyless Street (1925) and The Threepence Opera (1931).

Because of her Jewish heritage she was banned from performing on stage in Germany in 1933 and landed up in London where she tried her hand at short film acting (and also married her second husband). A few years later, in 1938, she emigrated to the USA where she posed as a nude model and washed dishes while plotting a return to being a cabaret artist yet again. In 1941 she opened the Beggar Bar with its iconic mismatched décor in New York and famously employed both Jackson Pollock and Tenessee Williams as bus boys. Williams apparently refused to pool his tips and Gert found his work “so sloppy”. Then came a move to Provincetown Massachusetts where she opened Valeska’s. Such was the macabre world of Valeska Gert that, after reuniting, then falling out with Tenessee Williams in Massachusetts, she still called upon him as a character witness in a court case accusing her of throwing garbage from her window and failing to pay a dance partner. (He obliged).

After riding out WW2 in exile, she returned to Europe in 1947, first Paris, then Zurich and her beloved Berlin, where she opened Hexenküche (Witch’s Kitchen) in 1949 and Ziegenstall (Goat Shed) on the island of Sylt. In the 1960s, she turned her hand to film again and acted in Federico Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits (1965), which led to various uptakes from young German directors, casting her in film and TV roles. When Werner Herzog remade Nosferatu, she was cast in a role, but passed away a fortnight before filming was to start, at the age of 86, on March, 16th, 1978. Her mailbox was allegedly full, containing umpteen letters from young punks who were hoping to meet her.

One may say that she was so ahead of the curve that audiences only decades later would play catch up and properly clock her contributions and unfathomable genius. In a talk with Radio Leipzig in the 1930s Valeska Gert commented on the quality of timelessness and universality of artistic contributions, saying, “Our works … will appear timeless to future generations only if they are profound enough. They will deliver a message which passes from generation to generation and which reveals that we are all human, we all have to follow the same laws, we all have to fight, we all have to die.”

Recently an exhibit at the National Gallery’s Hamburger Bahnhof celebrated Valeska Gert’s contribution to punk and her inspiration to Germany’s punk movement.