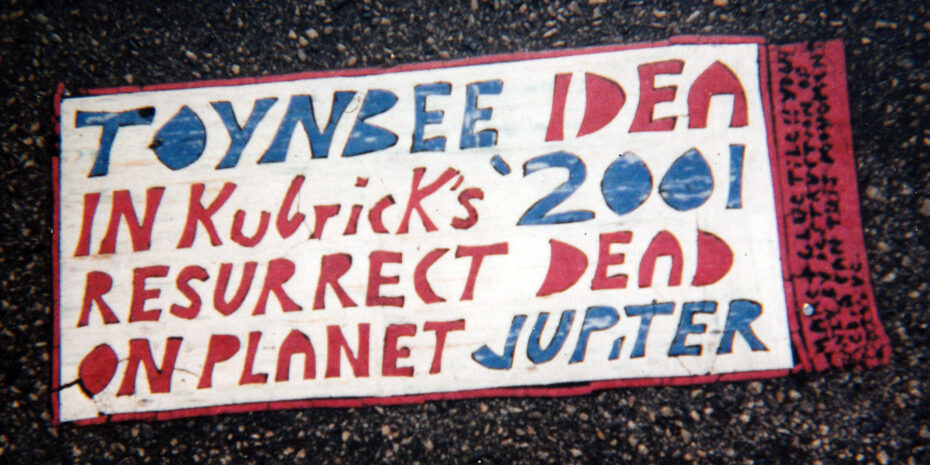

Imagine literally stumbling across a colorful tile in the road with some version of the bizarre inscription “Toynbee idea in movie 2001 resurrect dead on planet Jupiter.” This seemingly incomprehensible mambo-jumbo has flummoxed lovers of urban legends for decades, since they first started appearing in the late 1980s in Philadelphia, spreading to other North American cities all the way west to Kansas City and south to Santiago, Chile, and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Today, there are hundreds of these tiles, which are recorded on the website Toynbeeidea.com. Neither the meaning, nor the creator has ever been identified, though many theories have proliferated. We decided to dive into these bizarre public features and figure out once and for all if they’re heralding some future apocalyptic event, an incredible well-thought-out prank or just the work of someone with an overactive imagination.

Two main cultural touchstones are mentioned in the Toynbee tiles inscription. The first is English historian Arnold Toynbee, an expert in international affairs best remembered as the author of the 12-volume collection A Study of History. Published from 1934 to 1961, the universal history project detailed the rise and fall of many major civilisations, becoming an incredibly popular text before falling into obscurity. The second is Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey,” in which astronauts travel to Jupiter to learn more about a monolith created by aliens. (Note that both the movie and the planet are referenced in the Toynbee Tile text, but Kubrick was in fact inspired by the work of science fiction writer Arthur C. Clark.)

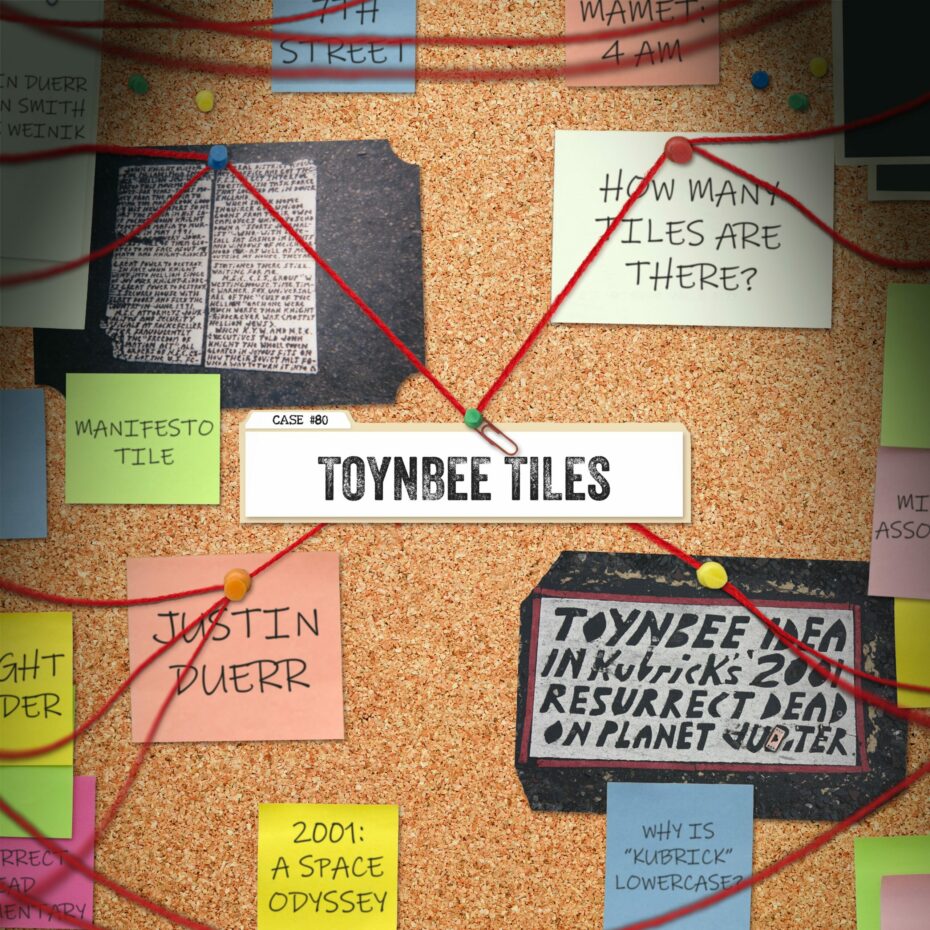

But these puzzle pieces don’t add much clarity to the tile’s meaning. And their mystery has intrigued many amateur sleuths over the years, including Justin Duerr, a Philadelphia musician and well-known figure in the city’s outsider art scene who first came across one in 1994. As someone who was just discovering his artistic practice, Duerr was inspired by the Toynbee Tiles creator’s prolific work ethic.

“One of the main reasons I was attracted to the tiles in the first place was just the sheer tenacity of whoever was behind them,” Duerr said in an interview with WQHS Radio. “I felt I kind of shared that tenacity in a way I could relate to emotionally. I would just go, ‘Man, another year went by and whoever’s making these tiles is still making hundreds of them!’ I almost felt that way with my creative pursuits because I never made any money doing stuff and never had any reason to do it.”

In fact, the person behind the tiles developed an ingenious way to make them last, by sandwiching them between two pieces of tar paper, with the pressure of cars rolling over it increasing the gluing bond over time. (They were often also placed in the summer, when the heat aided in wearing down the tar paper so the tile was revealed.) But the lettering and dark imagery that sometimes accompanied the tiles seemed almost amateurish, not unlike other self-taught and folk artists or even other street artists like Em Emem, who turns potholes into mosaic art.

Duerr began keeping a notebook documenting sitings and even made his first web search — in 1997 — looking for information about the tiles. Duerr also connected with others passionate about the tiles. One early lead was a tile in Santiago, Chile, bearing the Philadelphia address of a man named Severino “Sevy” Verna, though they were unable to contact him. They eventually discovered a March 1983 Philadelphia Inquirer article in which columnist Clark DeLeon describes a phone interview he had with a certain James Morasco. Morasco explained his theory that “Jupiter would be colonized by bringing all the people on Earth who had ever died back to life.” Sound familiar? Morasco identified himself as a social worker who had developed the theory by reading one Arnold Toynbee. He also quotes “2001: A Space Odyssey,” arguing that Jupiter’s atmosphere could be adapted to support human life, and mentions a mysterious body called the Minority Organization to advocate for this cause.

Mystery solved? Not so fast. When they contacted DeLeon, he had no way to connect the sleuths to Morasco. And yet another potential lead emerged: in his 1985 one-act play “4 A.M.” David Mamet tells the story of a man calling into a radio talk show to discuss Jupiter, resurrection and, of course, Arnold Toynbee. Mamet had in fact written the play in 1983, the same year as DeLeon’s article. While at the time, Mamet said the play was based on fiction, he later revealed it was inspired by listening to late-night Larry King call-in shows. And it could have been the person behind the tiles, as they often tried to reach out to the media to spread their message.

Duerr along with website moderators Steve Weinik and Colin Smith had a wealth of information, just as more mainstream media was gaining interest in the tiles in the 2000s. While searching through the sea of conspiracy theories, they learned that multiple people in Philadelphia had weird occurrences of their TV signals being interrupted by Tynbee Tile-related content. They also learned that the tiler had previously posted the message on wheat-pasted posters, which included a short-wave radio address. While immersing themselves in the world of short-wave radio, they put out their own pirate radio address. Some in the community happened to remember Severino “Sevy” Verna, whose address was on the Chile tile.

Back in Verna’s neighborhood, they learned from a neighbor that he had a car with a large antenna and the floor removed from the passenger seat: Was Verna using the antenna to interrupt broadcasts to share his message and discreetly placing tiles at the same time? Maybe so. Further, there were many smaller tiles around the house that seemed like they could have been practice attempts.

Later, Duerr heard from someone in the short wave radio community who had listened to a Toynbee radio address as a child that included a PO box address. He received a letter back — from James Morasco and the Minority Association. So it seems like Verna, using the alias of James Morasco, was behind Toynbee Tiles. But despite the evidence, the case has never totally been solved, given Verna’s desire to stay anonymous, something Duerr and the other researchers respected. (Duerr even claims to have had a face-to-face meeting with him.)

In fact, their search was covered in the 2011 documentary “Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of The Toynbee Tiles,” a low-budget project that ended up being shown at the Sundance Film Festival, even winning the Directing Award in the U.S. Documentary category. You can watch it in full below:

The film seemingly marked a Toynbee Tile revival, with a new wave of tiles popping up. In 2015, the Streets Department of Philadelphia even decided to officially recognise them as street art, agreeing to “save one or two of the Toynbee Tiles only if there is a fast and affordable method for removing them.”

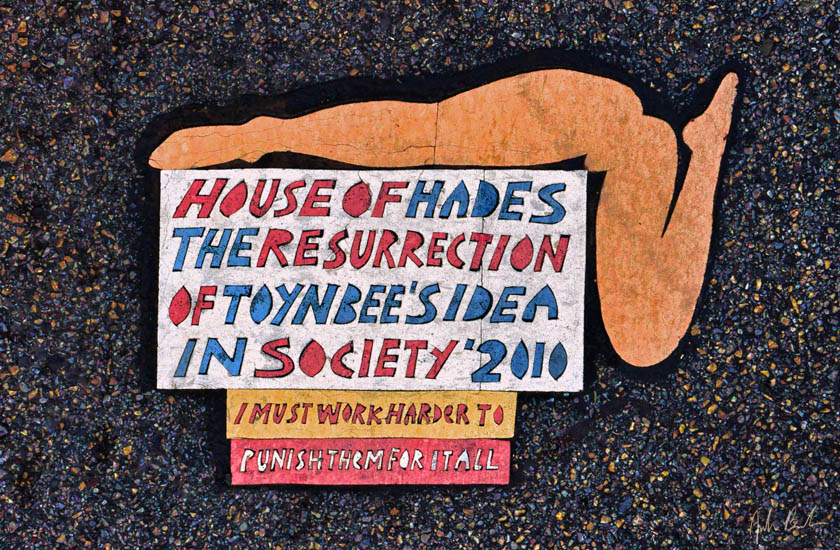

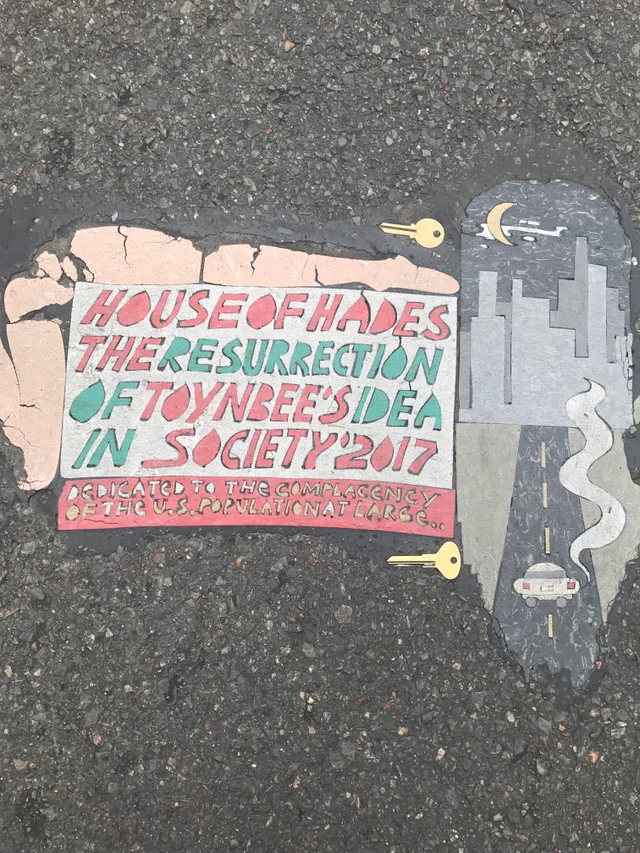

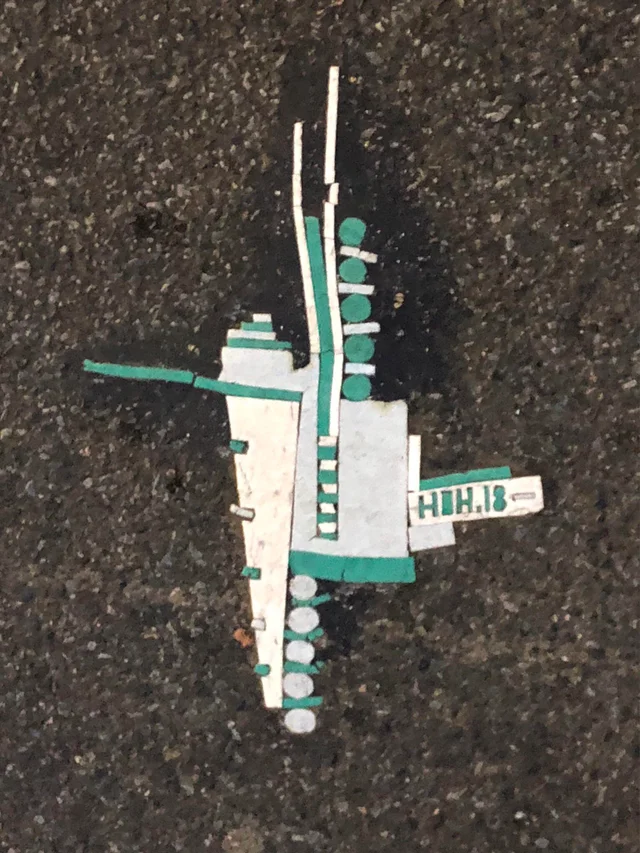

Even more interesting, new types of tiles started popping up. One style, which became known as the House of Hades Tiles, had a wider range of messages, often graphically attacking journalists using the phrase “one man against the media machine.” Some of them have been written in Polish and one even appeared in Japan at Tokyo’s famously crowded Shibuya Crossing. Duerr even says he met the House of Hades artist (wearing a ski mask) while performing with his punk rock band. Another set of tiles in New Jersey has specifically targeted a man named Mason Meltzer.

While we might never know the true, full story behind these works of popular art, their mystique is part of the charm. And Duerr has not stopped in his mission to “leave no stone unturned” in researching the work of outsider figures, like Philadelphian politician activist Kathy Chang (who died of self-immolation) and British cartoonist Herbert Crowley. Appropriately, when asked what he saw as the role of the artist in society, he told the blog Art Breakout, “Something in the universe is off kilter. This derailment is what the artist addresses – and, in some way, tries to fix.”