We need to talk about Beatrice Wood. The last surviving member of the American Dada movement, the ceramicist, the artist, the writer, the actress, the lover, and let’s not leave out, the inspiration behind the headstrong character of “Rose” in the movie Titanic. Beatrice was born at the end of the 19th century, and died at the end of the 20th, and in between she lived an incredible life. The sign on her ceramics studio read “Reasonable and Unreasonable”, and was a pretty spot-on description of her life.

Wood never set foot on the ill-fated Titanic, but after James Cameron came across her biography, he was captivated by her story of the free-spirited heiress and decided to use it as the backstory for the film’s fictional heroine. “My life is full of mistakes. They’re like pebbles that make a good road,” Beatrice once said.

Beatrice was born to wealthy socialite parents in San Francisco in 1893. Five years later her family moved across the country to New York city. The theme of her youth would become: “Her parents have plans for her; Beatrice has a different plan. Her parents try to support her plans, so Beatrice changes her mind again”. While her mother dreamed of a sophisticated daughter to introduce to New York society, Beatrice dreamed of art. Ironically it seems that her mother’s plans are the reason Beatrice was introduced to, and fell in love with, the art scene.

Beatrice was sent to France to spend time in a convent, and then be exposed to the arts and culture Europe. Upon her return to New York, she refused to politely enter society, and instead she hightailed it back to France. Under the care of a chaperone, she studied both theatre and art at the Académie Julian and had the opportunity to meet Claude Monet, and even watch him paint in the gardens of Giverny. In Cameron’s film Titanic, Rose refers to Monet when Jack paints her in the nude.

World War I effectively booted Beatrice back to New York where she (against her parents’ wishes) joined the French National Reparatory Theatre and found some success as an actress under the stage name “Mademoiselle Patricia”. In Titanic, we learn that after surviving the tragedy, Rose went on to be an actress in the 1920s among other things.

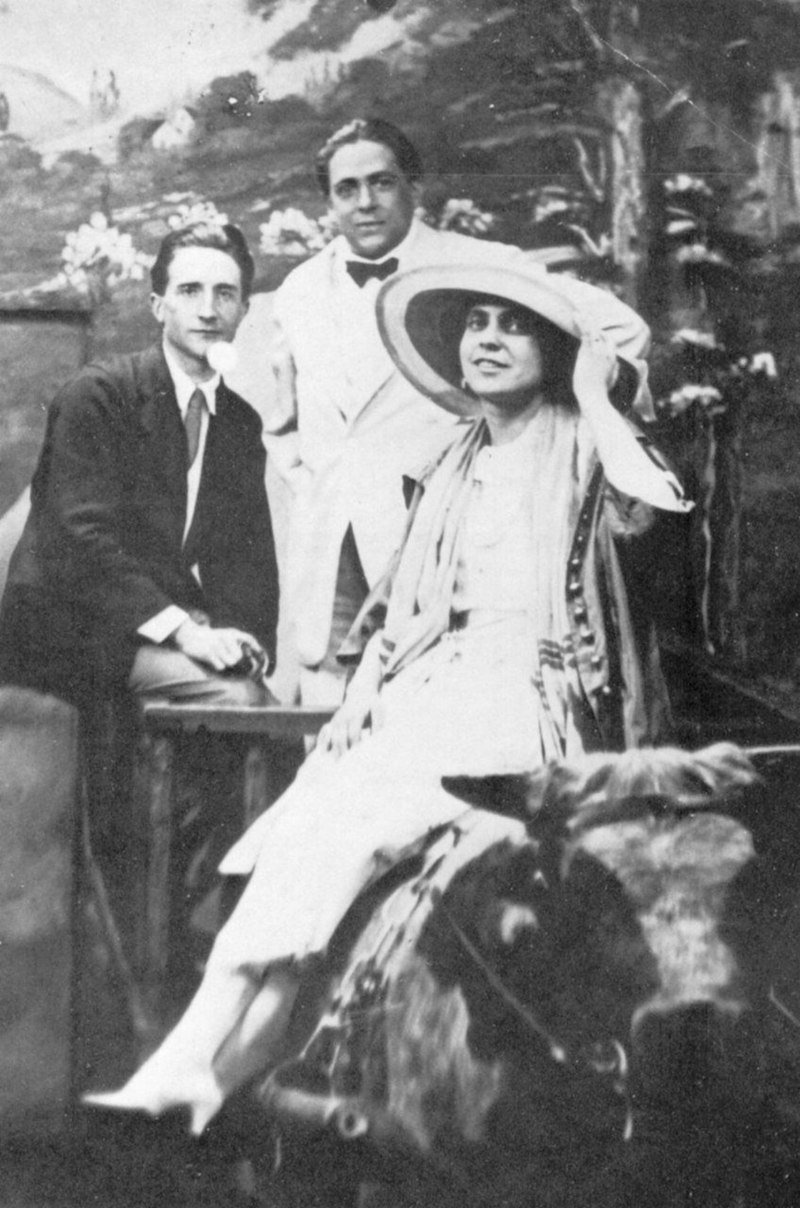

While in New York, Beatrice fell in love with a man – Henri-Pierre Roché – and an art movement – Dada. Roché was well regarded in the French avant-garde art world, and the couple were introduced by none other than Marcel Duchamp. Together with Duchamp and Roché, Beatrice created journals and publications of Dadaist art, notably The Blind Man in 1917. Modern Art as we perceive it was arguably launched by the quirky and wonderfully chaotic Dada movement, and between the years 1913 and 1923, they were the American ambassadors of Dada, moulding the New York art world as we know it today.

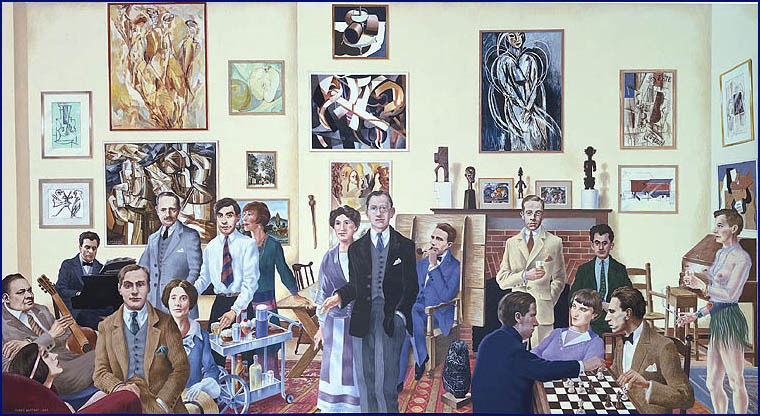

Walter and Louise Arensberg were wealthy art patrons who held regular salons. Beatrice, Duchamp, and Roché were part of this circle, along with Man Ray, Edgard Varese, Francis Picabia, and Joseph Stella. This period is when Beatrice acquired her famous nickname, “The Mama of Dada”. As for her relationship with Roché and Duchamp? Well, speculation on their love triangle exists to this day.

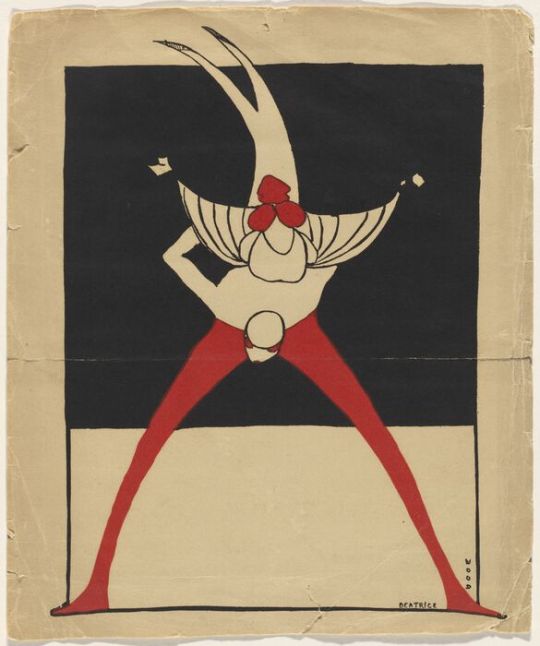

During this time, Beatrice began to form an identity as an artist, drawing and sketching. “She created an abstraction to tease Duchamp that anyone could create modern art,” writes Beatricewood.com. “Duchamp was impressed by the work, arranging to have it published in a magazine and inviting her to work in his studio.” Beatrice would exhibit her work with The Society of Independent Artists, and continue to contribute to art publications. Famously, she defended her friend Duchamp’s controversial urinal piece Fountain, but today it’s difficult to find Beatrice’s own Dada work and frustratingly, her name does not often hold the same gravitas of her Dada contemporaries.

In the 1920s, Beatrice moved to Montreal to be part of the theatre scene again but once again, she quickly grew tired of life as an actress.

“You know, acting is very fascinating. But being an actress is not, because you become so concentrated on yourself. And your smile and the way you move your head and the way you look. And really, it’s a pain in the ass.” – Beatrice Wood.

She was briefly married, but soon after, her parents arranged for it to be annulled – no love lost there on her part – she never really cared for the man and once claimed she “never made love to the men she married and never married the men she loved”. Upon returning to New York, Beatrice found that her beautiful world of art and lovers had broken apart. Dadaism was in decline, and both Duchamp and Roché had returned to Europe. The Arensbergs had moved to Los Angeles, so the salons she once frequently were gone too.

She fell in love again, this time with British actor and director Reginald Pole. Their relationship was intense, but in the end he broke her heart when he fell in love with someone else. Around this same time, Beatrice was becoming a follower of Jiddu Krishnamurti, member of the Theosophical Society, as well as a writer, speaker, and mystic. Painting, theatre, Dadaism; these are all part of Beatrice Wood’s legacy, but perhaps the art she is most famous for is her work in ceramics.

Beatrice ended up moving to Los Angeles to hear Krishnamurti speak more regularly, and then followed him overseas to Holland, where the first inkling of creating ceramics came to her. She had purchased a beautiful set of baroque dessert plates with a stunning luster glaze. She searched for a teapot to go with her set, but was unable to find one. Frustrated, she decided simply to make one of her own. Back home in California she enrolled in her first ceramics class in 1933.

Beatrice would be a prolific ceramic artist, but she herself felt that it did not come naturally to her. She worked hard at learning this craft, particularly studying glazes. She said, “… I could sell pottery because when I ran away from home I was without any money. And so I became a potter.”

Throughout the 1930’s, Beatrice continued to study pottery. Alyson Brandes of the American Museum of Ceramic Art writes this about Beatrice: “It’s not surprising that Wood transitioned from the Dada movement to clay – ceramics has a history of being the “outsider’s” material of choice, with room for endless possibilities in form, glazing and firing, and Wood was up for the challenge.”

Beatrice was a student of Glen Lukens, and then Gertrud and Otto Natzler. She was an eager learner, who embraced her own limitations. Traditional learning structures didn’t suit her, so she learned what she could, and applied her own unique style to her work; often earthy, with organic shapes, and her glazes are stunning. In fact, a rift would develop between Beatrice and the Natzler’s when they accused her of copying their work too closely.

By 1947 Beatrice was exhibiting her ceramic work in Los Angeles and New York, and was fulfilling orders from all over, including places like Nieman Marcus. She decided to move to Ojai, California, and continued her career there. It was no coincidence that Jiddu Krishnamurti was also in Ojai. Beatrice felt close to him, and wanted to continue to incorporate the values he espoused into her daily life. She became a member of the artistic community there, and when a friend encouraged her to build a home and a pottery studio at the Happy Valley Foundation she did, and taught ceramics classes at the school.

Her pottery career continued to soar, leading her to show her work as far away as Japan. Her work stood out as vivid, colorful, and playful. Like some of her Dada art, some of her ceramics were erotic, which also brought her attention. In 1961 the State Department invited her on a tour of India, where the colours and imagery became an integral part of her work.

In her eighties, Beatrice became a writer. Her first work was The Angel Who Wore Black Tights. She developed a friendship with Anaïs Nin, who encouraged and helped her to write her most famous book, I Shock Myself, the autobiography that would serve as James Cameron’s inspiration for the character of Rose in Titanic. This is Beatrice’s autobiography. After that came Pinching Spaniards and 33rd Wife of a Maharajah: A Love Affair in India. Remember the scene in the beginning of the movie when we get to see a glimpse of Rose’s beautiful house while she works away on her pottery wheel?

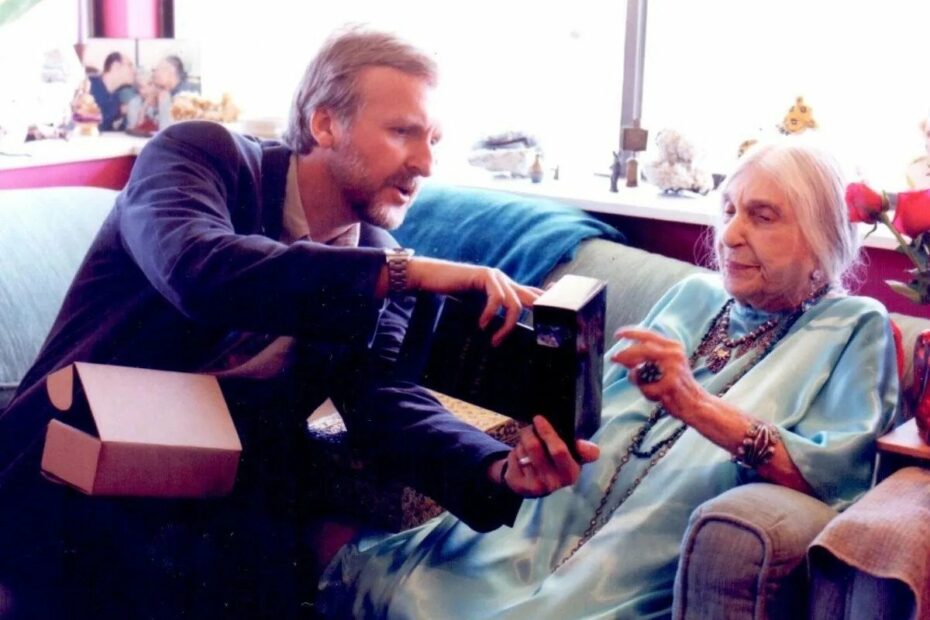

Beatrice was invited to attend the premiere of Titanic but was too ill to make her red carpet appearance. The actress that played her in her old age, Gloria Stuart, and James Cameron visited Wood on her 105th birthday and gifted her a VHS copy of the film. She claimed she never watched it because “It was too late in life to be sad.” She died nine days later.

It seems that Beatrice was woman who followed her passion, and left her mark throughout the 20th century. She may not be as well known as some of her friends and contemporaries but her fingerprints are all over the place. When asked about her longevity she replied that it was all due to “art books, chocolates and young men”.