‘A bandstand is, merely an empty shell unless music is played upon it,’ so laments Pavilions for Music, a website dedicated to the humble bandstand. Indeed, these empty shells with their elaborate ironwork and faded glamour, rushed past by commuters, utilised as climbing frames by children, smoked upon by teens and generally taken for granted in parks and resorts across the world, have a surprisingly interesting story to tell and, if recent efforts are anything to go by, hopefully a more exciting future ahead.

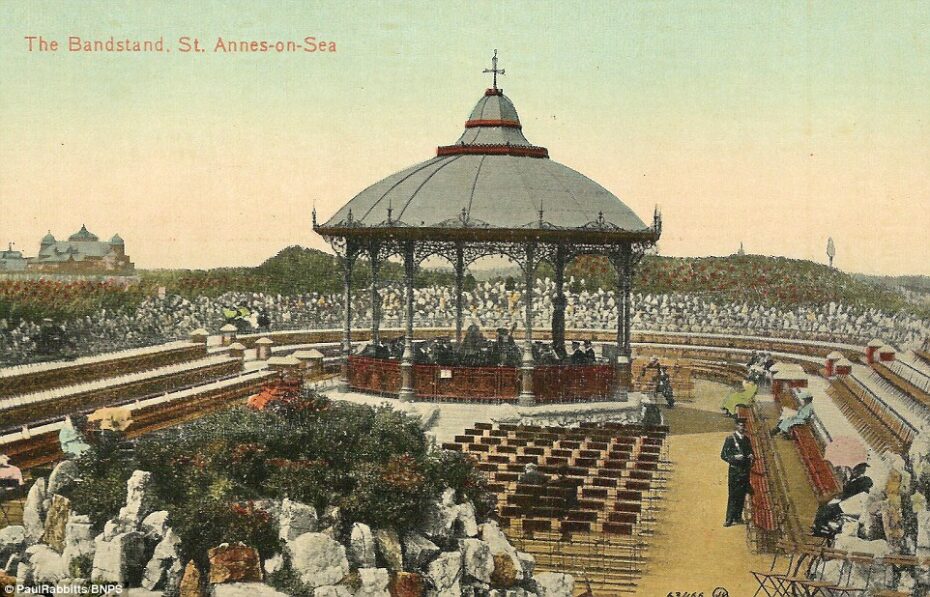

Conjure, if you will, the image of a public park on a warm summer’s day; what do you see? You have probably envisioned a landscape of formal flower beds, sweeping walkways with benches dotted alongside, and in the centre of all this, the bandstand; an octagonal, oriental and opulent masterpiece of ornamental ironwork.

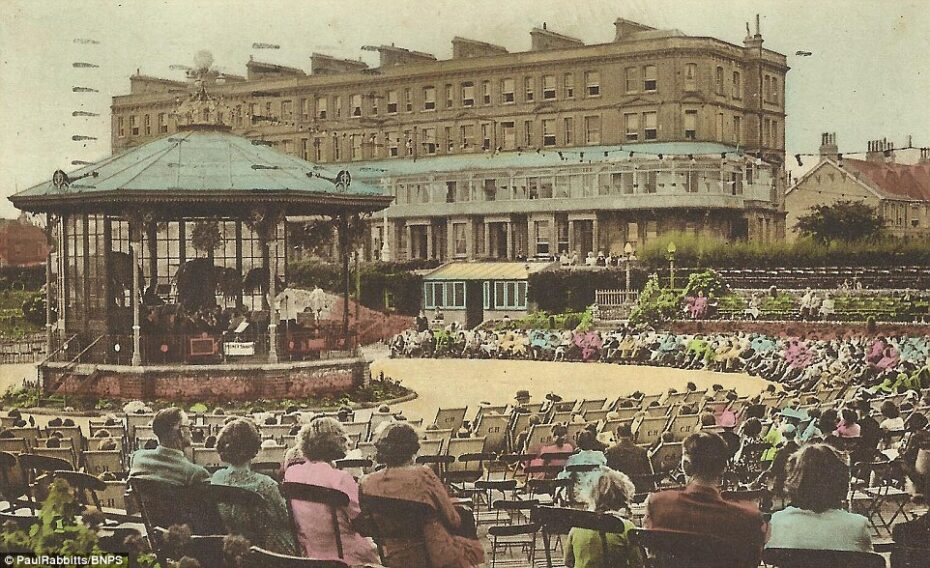

As quintessentially British as bunting, brass bands and the summer fete, bandstands have been a feature of an idealised summer for over a century, however, after the Second World War, most fell into a state of disuse and disrepair, towns and cities, not only in Britain but throughout Europe, almost losing these pillars of tradition altogether. At the peak of their popularity, Britain claimed over 1200 bandstands in her public spaces, a number reduced now to less than 500.

So what is the story of the bandstand and how did it mushroom across our tamed landscapes in the first place? In the UK, the first domed bandstand as we have come to recognise it, originally called a ‘band house’, is thought to have been erected in the Royal Society of Horticulture South Kensington Gardens, London, in 1861. Two elements coincided at that time; the industrial iron-age alongside the development of councils creating municipal parks and green areas in which urban dwellers could escape the choking pollution, often caused by these very ironworks as well as the other multitudinous factories galloping across the land. In October 1859, the Middlesborough Advertiser declared:

‘No place is so badly provided for the recreative department as ours […] sickly looking youth and pallid manhood would receive a boon indeed by the establishment of […] the enclosure of some ground where cramped limbs might be exercised, and the mind dragged from the everlasting monotony around us […] it is paramount opinion everywhere that we live in the smokiest, unhealthiest hole’

Each of these parks was given a focal point and bandstands, which were not only decorative but could provide entertainment in the form of music, were the clear choice. British Victorians were not known for their musicality, however in a blog run by the University of Kent, Daniel Harding describes the rise of the brass band at the same time as bandstands were beginning to emerge:

‘The lower classes experienced wage increases, particularly in the 1860s to 1890s, while, concurrently, ‘music for the masses grew at unprecedented rates’. Band competitions started in 1853 with the Belle Vue Contest, choir festivals began in 1855 in Manchester (excluding the notable history of Welsh choir competitions, of course), and ‘by the end of the century, there were thousands of brass bands and choral societies in Britain’. More people were able to ‘participate in music-making’, and, importantly, ‘concert attendance rose mid-century as rural and urban workers took advantage of this newly available entertainment’.

According to Pavilions For Music, these bandstands, exotic in design, became enormously popular, drawing crowds of up to 10,000 in the UK. For example, when the arboretum in Lincoln erected theirs in 1884 its band concerts were soon attended by over 40,000.

Is it not strange then, that these fixtures of Victorian parks, evoking all things British should look quite so, well, foreign? Maybe not. There is a theory that this design trend was started by the fantastical music pavilion erected in London’s fashionable Vauxhall Gardens at least fifty years earlier.

Coloured aquatint, Thomas Rowlandson.

Making bandstands in evidence today appear plain in comparison, Vauxhall’s could have been transported from a Mughal palace, or from the pages of the Arabian Nights. It can be no coincidence that European empires were growing rapidly at this time, especially via the East India Company and its counterparts, and oriental designs were de riguer across the continent. Britain’s empire peaked during the Victorian era, when most of these bandstands were commissioned and seemingly west was not always, as was so often proclaimed, best.

In a wonderful essay by Barbara Jones, published by The Architectural Review in 1947, celebrating the British seaside resort, another objective of such exoticism is suggested:

‘in the vilest weather they still manage to convey a feeling of oriental warmth, or suggestion that today is only cold by a very curious accident […] bringing an illusion of the Riviera to the less favoured coast of Sussex.’

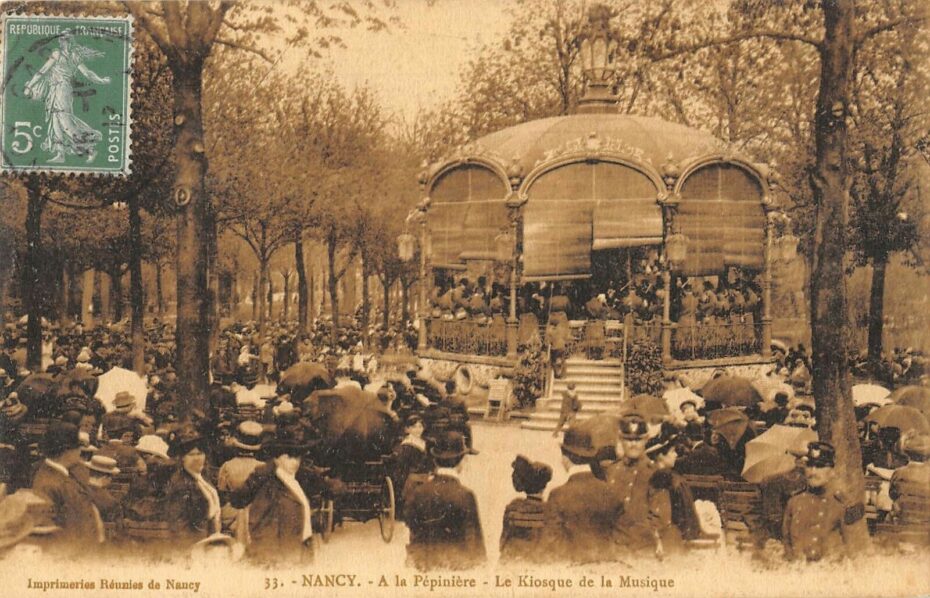

France’s nineteenth century bandstands were equally fantastical, often designed by Adolphe Alphand, the architect of much of Paris’ arabesque park furniture, and it is also interesting to note that in France ‘bandstand’ translates as kiosque à musique. The word kiosk originates from the Turkish köşk, and the Persian kūshk, describing the garden pavilions common in both of these countries as well as in India and other parts of the Ottoman Empire, adding yet another layer to their sense of otherworldliness.

Sadly, the British love affair with bandstands dwindled and by the late 1940s, many had been boarded up or reached a state of disrepair. During World War Two, frivolous iron fittings had been removed from them in order to be melted down for artillery and their popularity wained, unable to compete with modern entertainments like the cinema, television and radio.

It was broken up on 27 July 2009 Ì blackpoolbeach

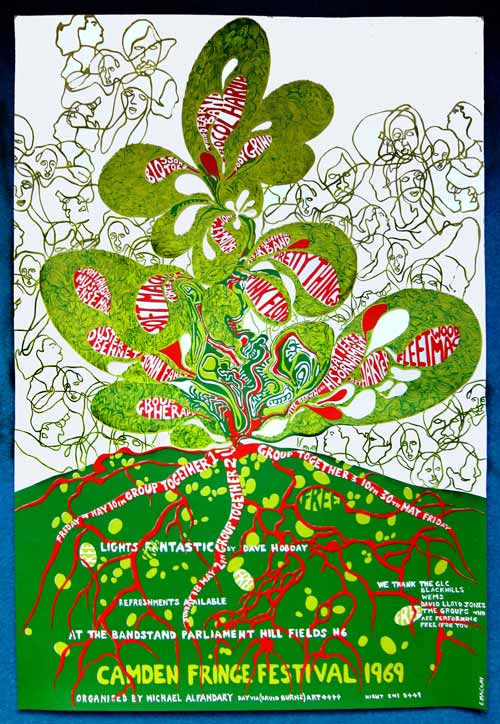

There was a brief renaissance in the late Sixties when Pink Floyd and Fleetwood Mac played in a series of free concerts at Parliament Hill bandstand as part of the Camden Festival in London. Three weekly parties were thrown in May, kicked off by Pink Floyd and attended by a large crowd of hippies. Dodgy PA systems and feedback clearly hadn’t put people off as by week two the crowd had doubled, and by the third week, when Fleetwood Mac played, 25,000 people thronged to hear them. In true anarchic Sixties style, the band’s set didn’t begin until after midnight but was cut short after only two songs after a group of anti-hippie skinheads arrived, pelting the band and crowd with bottles and coins.

Bandstands also enjoyed a brief moment in the spotlight in 1968, making an appearance in The Beatles’ film The Yellow Submarine in which the band find a grand bandstand, conveniently complete with enough instruments for them to recreate Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and liberate Pepperland from the Blue Meanies. The Pepperland musicians have been trapped on their bandstand inside a huge bubble and are marvellously freed by Ringo.

Between 1979 and 1996 however, most of the UK’s bandstands were demolished, vandalised or simply left to rot, abandoned but for groups of teenagers, the homeless or graffiti artists; their music silenced.

The story of the bandstand does not end there however. In 1996, the Heritage Lottery Fund began a program to save the UK’s public parks and gardens, and mercifully, what Dr Stewart Harding, its former director, described as the ‘wonderfully exotic structures that are at once very familiar and also alien in their strange designs – looking like UFOs, Moorish temples, rustic cottages or Chinese pavilions’. Since then, over 100 bandstands have been restored to their former glory, including those in Crewe, Wigan and Sheffield.

A similar project has seen thirty three bandstands repaired in Paris since 2016, adding electricity and lighting to boot. During the recent pandemic, Paris’ kiosques à musique became the venue for a series of outdoor concerts, facilitated by Mary Ann Warrick, a Parisian with a passion for melody. When Covid struck, she originally kept public music alive by recording concerts from her living room, and broadcasting them under the name Chez Nous/Chez Vous, but after spotting a proposal by the City of Paris to animate the kiosques this year, she pulled together a plan for twelve bandstands to host a summer long series of concerts called Les Concerts-Promenades, which saw Paris thrumming in the open air right through to October.

Happily then, the future seems to be looking up for bandstands. Empty shells no longer, they are once again focal points for outside entertainment across towns and cities, echoing to the beat of music old and new. Britain too has seen a rise in al fresco living; summers are awash with festivals, musical, literary or artistic, despite the unpredictable weather, and once empty streets are lined with tables designated for outdoor dining – braziers and blankets supplied. Never have our open spaces been more in demand than during the pandemic, and whether as venues for traditional brass bands, a classical quartet or a rock and roll band, long may our exotic, flamboyant and eccentric bandstands live.