Cairo, 1938. Around 140,000 British troops occupied the city, and World War II was ready to burst. Thirty-seven artists and writers gathered to fight against a rising Fascist ideology, British colonial rule, and the local conservative art scene. The first inklings of Surrealism already simmered under Egypt’s troubled surface, as artists and writers corresponded with Western Surrealist giants like André Breton – founder of the movement – and photographer Lee Miller. But things came to a boil at the end of 1938 when the Egyptian group released their manifesto: “Long Live Degenerate Art.” Art et Liberté was the name of their movement active from 1938 to 1948, giving Egypt the surrealist voice it needed to battle politics with art, embarking on a mission rooted in social and moral revolution. Through art, the Egyptian surrealists championed causes ranging from women’s rights and feminist issues to colonialism, Fascism, and police brutality. Although the movement shook Cairo’s streets almost a century ago, the group’s commitment to social justice resonates even today. Going beyond global and political issues, members of Art et Liberté also dug – like British archeologists in the Valley of the Kings – into themes of Egyptian identity by exploring folk stories and Coptic (a North African Christian ethno-religious group) religious art in their work. This period of Egyptian Surrealism lasted ten years, but it was fruitful, packed with struggles for aesthetic and political activism.

Art et Liberté was born out of protest as a backlash to the highly conservative Salon du Caire; an annual art event run by the Societe des amis de l’art. It was no small event, and it pulled in up to 55,000 visitors, but Art et Liberté detested how the Salon classified artists according to nationality.

“We find absurd, and deserving of total disdain, the religious, racist, and nationalist prejudices that make up the tyranny of certain individuals who, drunk on their own temporary omniscience, seek to subjugate the destiny of the work of art,” declared the manifesto.

The group despised nationalistic art and art for art’s sake. They reclaimed the term “degenerate,” following the Nazi use of the term for art and writing that did not align with the nationalistic and Fascist party line. Social and moral revolution was the name of the game, and their movement pulled in hungry and angry creatives and intellectuals.

“This hostility is appearing today in totalitarian countries, especially in Hitler’s Germany, through the most despicable attacks against an art that these tasselled brutes, promoted to the rank of omniscient judges, qualify as degenerate,” stated the manifesto, “Vienna has been left to a rabble that has torn Renoir’s paintings and burned the writings of Freud in public places. The best works by great German painters such as Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Karl Hoffer, Kokoschka, George Grosz and Kandinsky have been confiscated and replaced by Nazi art of no value. The same recently took place in Rome where a committee was formed to purge literature, and, performing its duties, decided to eliminate works that went against nationalism and race, as well as any work raising pessimism.”

Art et Liberté also championed home-grown issues that sadly wouldn’t be out of place today. Greek-Egyptian artist trained in Paris, Mayo, criticised police brutality in his Coups de Batȏns (1937). Women’s rights to freedom and life were expressed in Kamel El-Telmisany’s Untitled (1940), depicting women being crucified, a metaphor for their suffering and crucifixion by circumstance, life, and war.

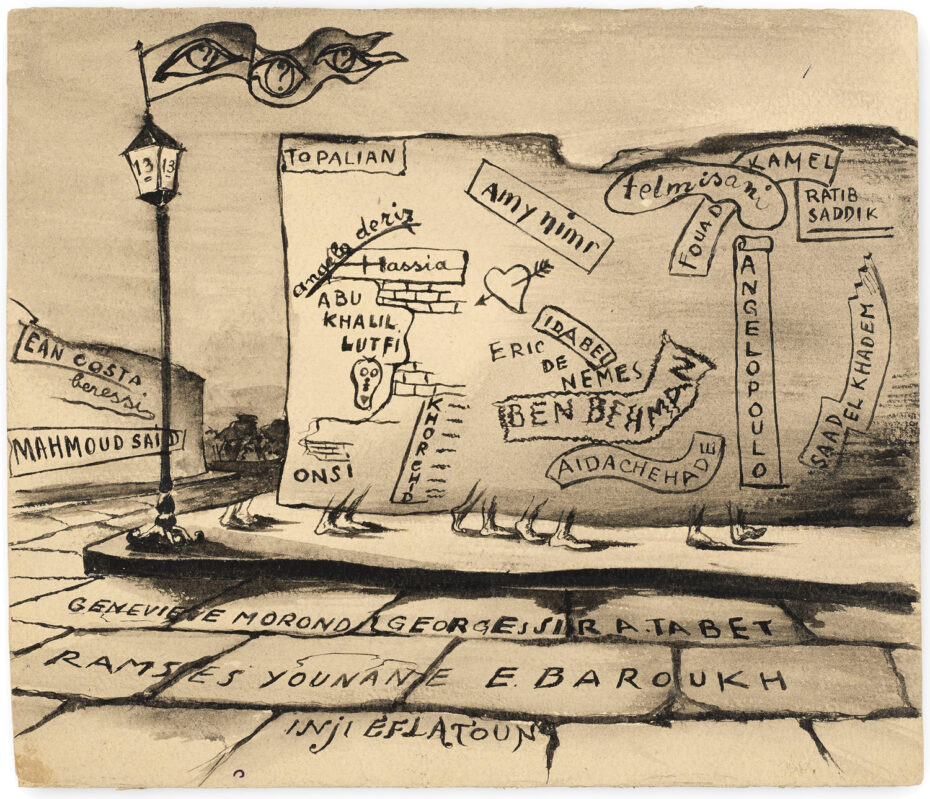

One of the core founders was the eccentric George Henein, a provocative poet and radical publisher, who penned the manifesto and was essentially Art et Liberté’s link to the European surrealists. He came from a mixed background, with a Coptic diplomatic father and an Italian-Egyptian mother. Before studying at the Sorbonne, he spent a cosmopolitan childhood between Cairo, Madrid, Rome, and Paris. He fell in with the surrealists in Paris, becoming friends with André Breton and Henri Calet. Henein continued his correspondence with Breton after he returned to Egypt as he looked for a way to fuse Marxism and Surrealism. Others who signed the manifesto came from diverse backgrounds of Muslims, Jews, and Copts, and you’d find both Egyptian and immigrant names inscribed on the manifesto.

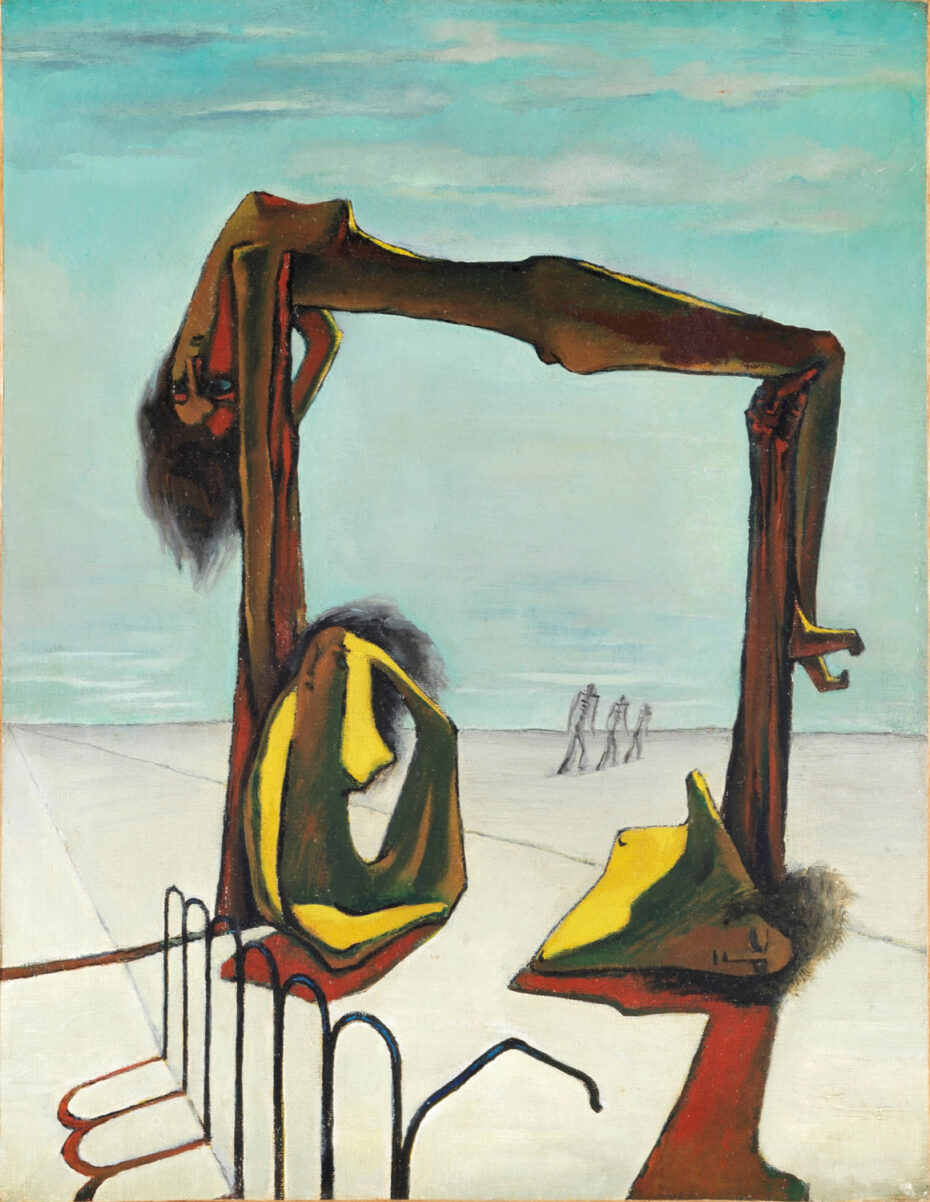

The artists condemned the Egyptian government and its nationalism. Like how the Nazis drew from Germanic lore, the Egyptian government propaganda also found inspiration historical inspiration in Ancient Egypt, particularly from images of the pharaohs. Art et Liberté reimagined these Pharaonic images into provocative ones. Ramses Younan, a Coptic-Christian artist who translated Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell into Arabic and distorted Pharaonic mythology in his work, depicted a twisted, broken, and contorted Egyptian goddess in his Untitled (1939), an allegory to Egypt at the time. Ida Kar, an Armenian-Russian artist who grew up in Alexandria, also used twisted images of Ancient Egyptian imagery in L’Entreine (1940), where she used ribs in place of temple columns.

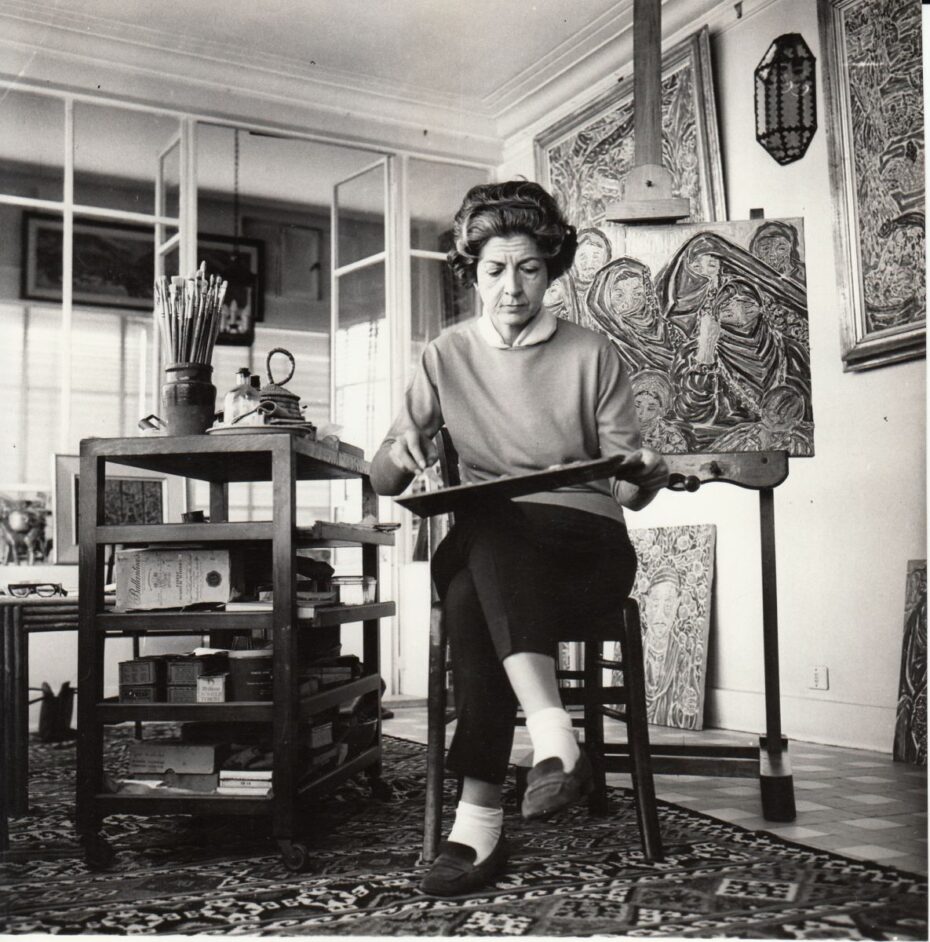

Although Surrealism, in general, tends to have a reputation for being a boys’ club, with notable exceptions like Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, and Dorothea Tanning, the Egyptians had a core group of women artists at its heart. Inji Aflatoun was a leading spokeswoman for the Marxist-progressive-nationalist-feminist movement and a pioneer in modern Egyptian art. Kamal El-Telmissany taught her to paint, but she would surpass him in her reputation as an artist, becoming one of Egypt’s best-known modern painters, even though she would spend much of the 1950s in prison for her communist views.

Then there Joyce Mansour, a surrealist poetess and Amy Nimr, a writer and artist who linked the group with prominent British Surrealists and writers Henry Miller and Lawrence Durrell. Aflatoun and Nimr made feminism a central issue in their work.

The men in the group also championed the cause for women’s rights, mainly through Kamel El-Telmissany’s journal Al Tatawwur, the first avant-garde, surrealist, and Marxist-libertarian publication to come out of the Arab world. Al Tatawwur was edited by Anwar Kamal, who stated the magazine would “defend the freedom of art and culture, to spread modern literary works, and to Egyptian youth with international literary, artistic, and social movements.” Prostitution, sex, and women’s sexual freedom were frequent topics. The journal cemented the authority of the Egyptian surrealists and even published work from international surrealists in translation, like the French poet Paul Éluard. Al Tatawwur was published monthly until July 1940, when Egyptian authorities closed the journal down and jailed Anwar Kamel for his writing.

Henein, drawing by Fuad Kamel

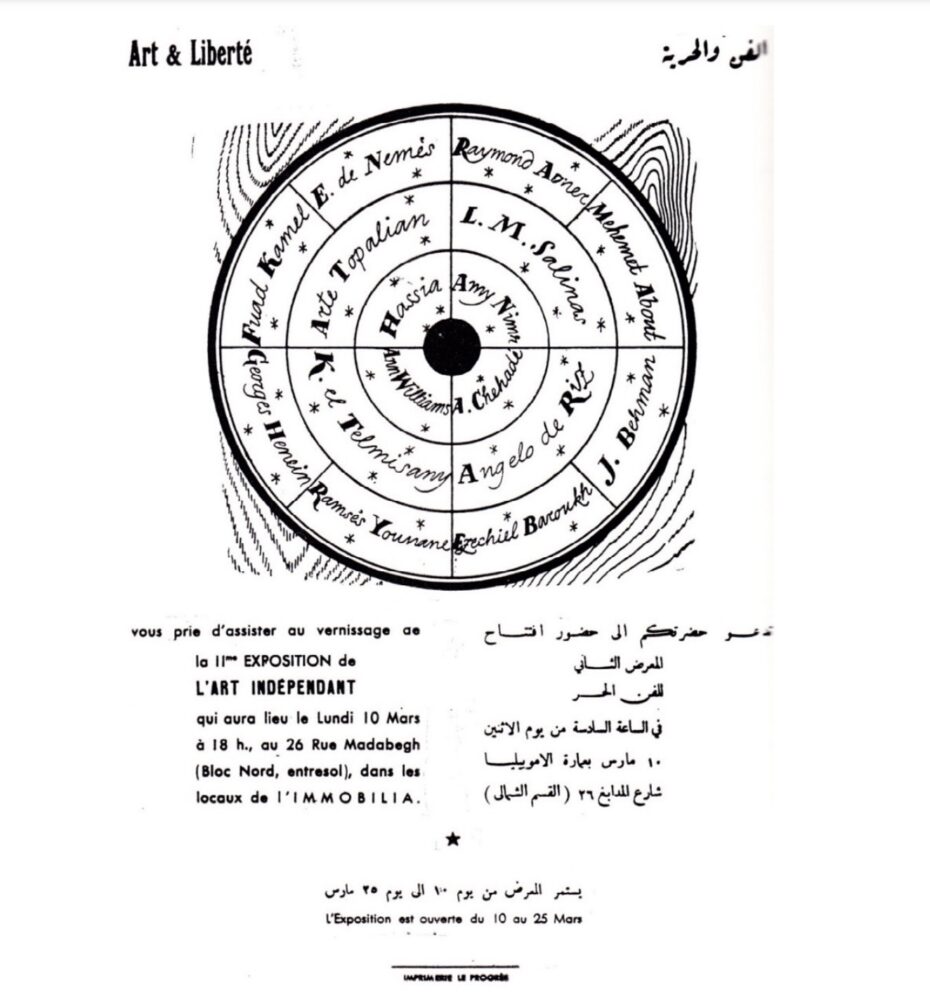

Although their journal was controversial, Art et Liberté continued to hold group exhibitions from February 1940 until May 1945, but from the late 1940s and early 1950s, the group began to unravel and disband. Both Kamal El-Telmissany and George Heinein withdrew from the surrealist movement in the late 1940s. Ramses Younan left Egypt for France after spending time in prison before moving into the Parisian surrealist circle and eventually abandoning Surrealism for abstract art. Ida Kar moved to London in 1945 and connected with British Surrealists. The members who stayed in Egypt would be impacted by the political changes in Egypt following the coup led by General Nasser in 1952, causing some members to flee the country into exile, like Amy Nimr, while others, like Inji Aftaloun, were imprisoned. History forgot Egypt’s surrealists; some even wrote them off as copycats of the Western Surrealists. Still, when you look at their work more closely, their values and political activism, you uncover an exciting art movement that’s anything but superficial – with a message that’s still as relevant in the 21st century as it was in 1940s Egypt.