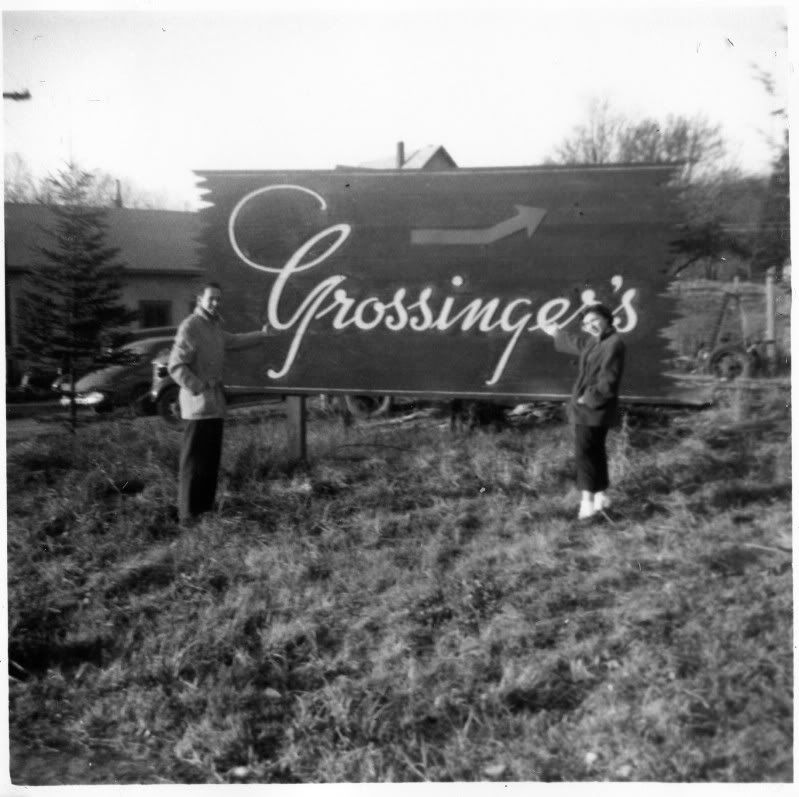

Whilst exploring the abandoned Grossinger’s holiday resort in New York’s Catskill mountains one last time before it was torn down, something caught our eye in the crumbling ruins of what had once been the ice skate house. Propped up against the wall was a large wooden sign that had been left behind. Dusty like a long unused chalkboard and covered with autumn leaves, the sign was an old scoreboard for something called ‘North American Invitational Barrel Jumping’. It was only after conducting research later that we discovered this old scoreboard was perhaps the last remnant of a bygone sport, the weird and wonderful world of competitive barrel jumping.

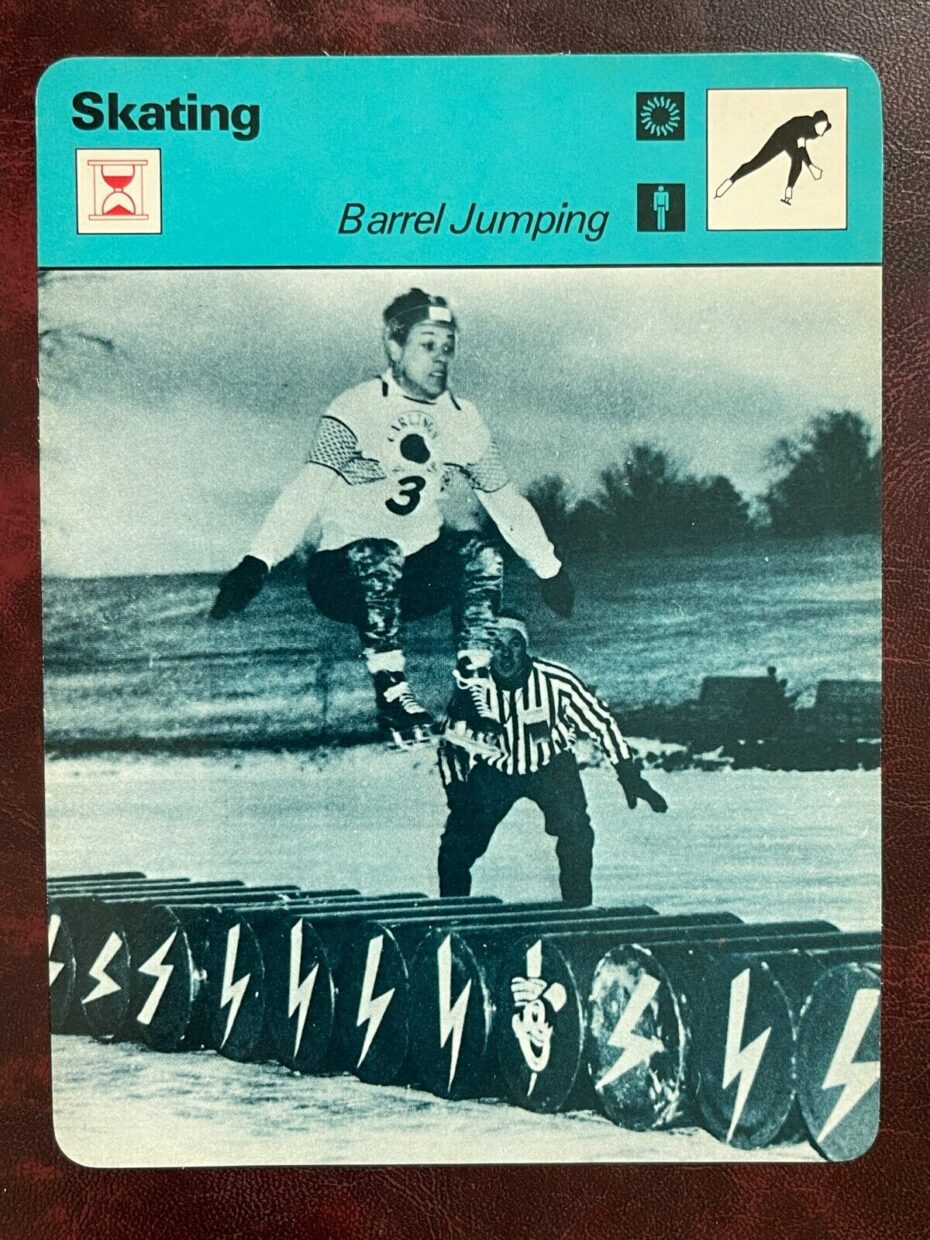

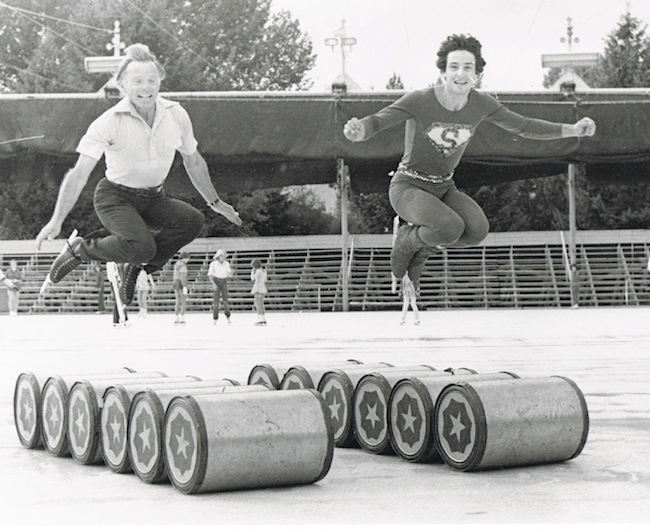

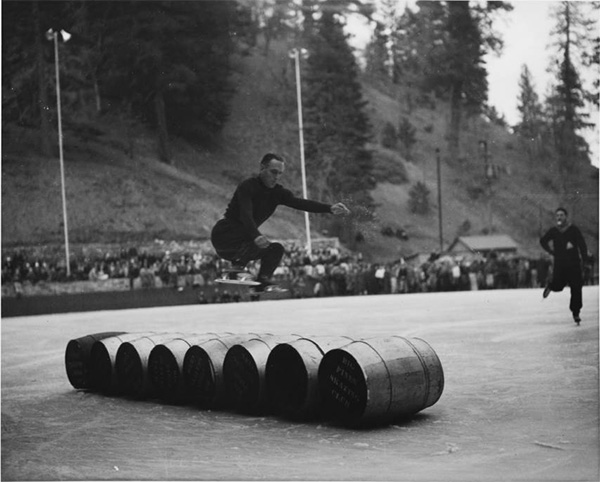

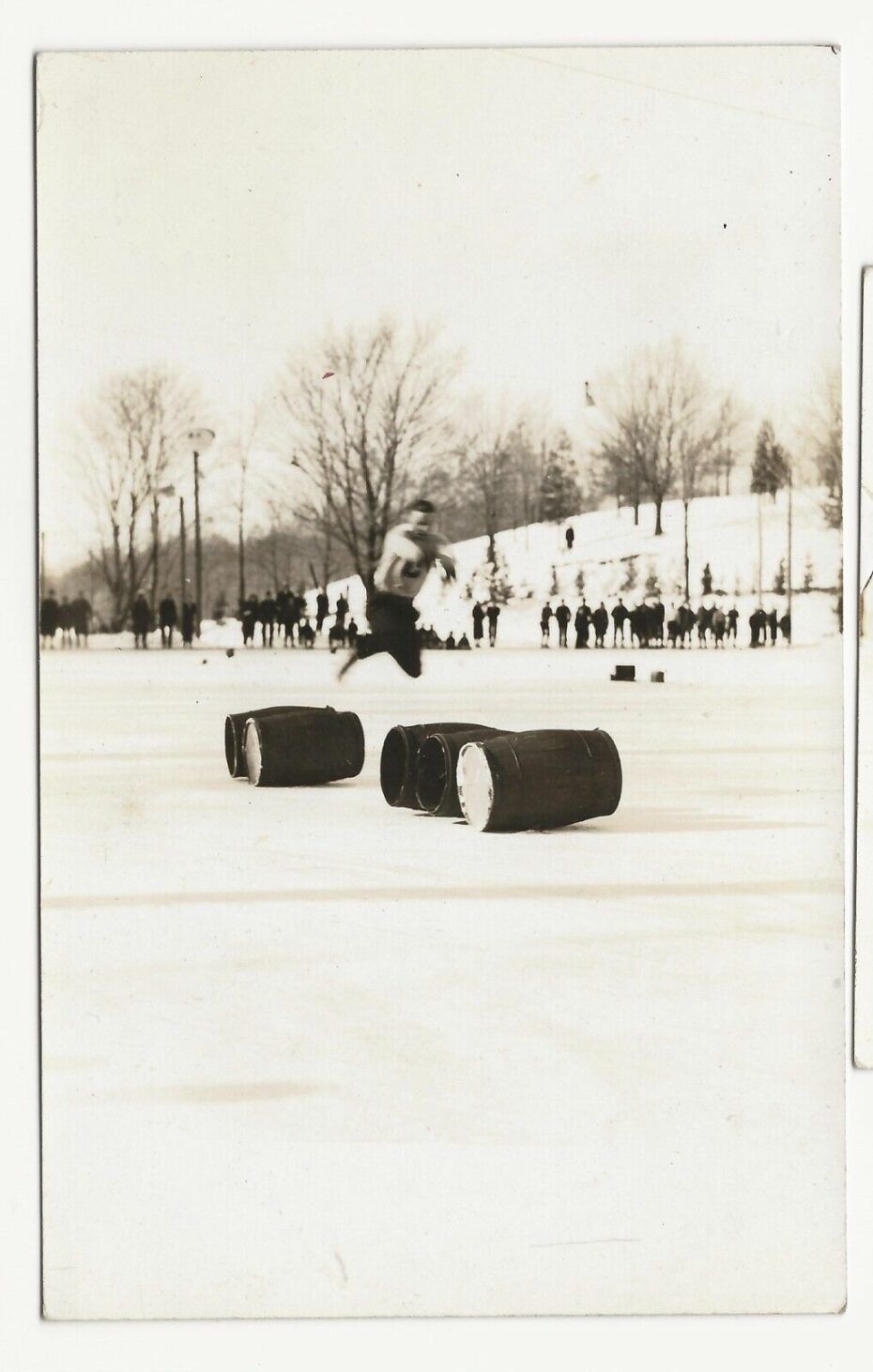

Barrel jumping is a sadly lost ice sport with the simplest of rules: intrepid skaters would circle a rink at increasing speeds before launching themselves into the air over as many lined up barrels as possible. In essence it looked a lot like the long jump in athletics, only with the flashing blades of the skates, high speeds, and the prospect of a terrible crash onto hard ice at the end of it, and that was only if you cleared all the barrels.

“It requires a lot of courage. Why, some of those boys are going fifty miles an hour when they’re over the barrels,” explained one of the sport’s organisers back in the 1930s. “Once we tried to lengthen the landing space so the jumpers wouldn’t crash so hard. They refused to allow it. They wanted less landing room so they could have more space to skate and build up speed for their jumps. These guys are wild men.”

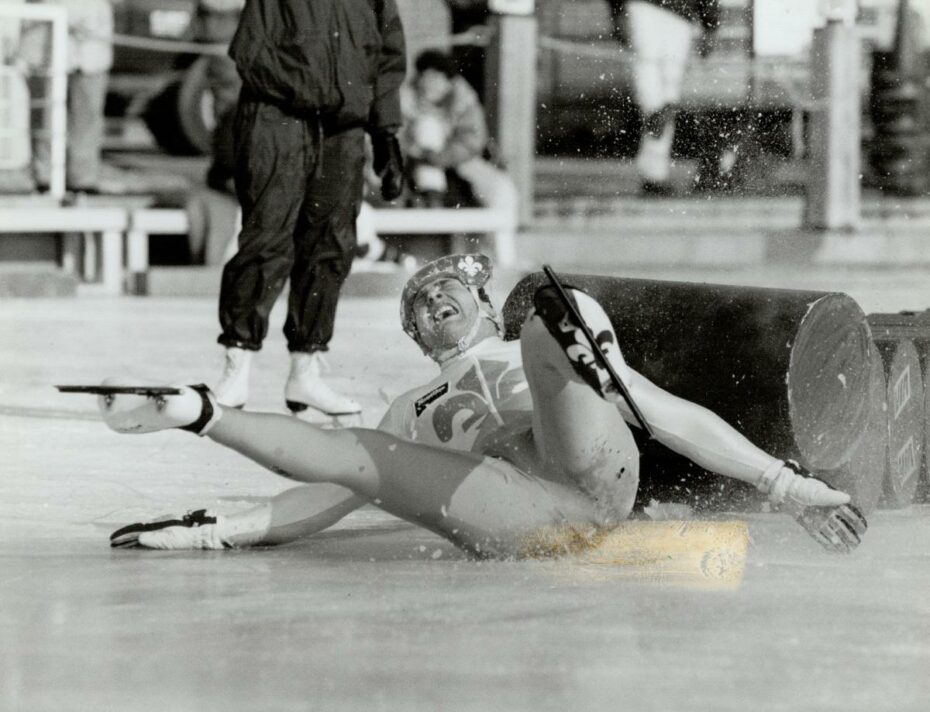

Broken ankles, a shattered pelvis and cuts that required three rounds of stitches were common in what was perhaps the grandfather of today’s extreme sports. Barney Ross, the late boxing champion, once said, “I’d rather take 15 rounds of punishment in the ring than do what those barrel jumpers do.”

“We must have speed and guts,” declared Gilles Leclerc, former president of the now obsolete Canadian Barrel Jumping Federation. For decades, the federation lobbied to have the sport included in the Winter Olympics, even sending a live demonstration team to the build up of the 1994 Lillehammer games in Norway. First watching a video of barrel jumping in action, the Olympic Committee were horrified; Tor Aune, a member on the Organising Committee said, “It appeared to be a brutal sort of sport. Everybody falls on their backside.” The live demonstration was canceled, and the sport died out soon after.

Barrel jumping was thought to have originated in Holland in the 19th century when Dutch daredevils in the winter months would jump in their skates over obstacles like fences, gates, and then beer barrels, perhaps after drinking what lay within. The advent of speed skating as a sport in the 1920s saw barrel jumping evolve, but it was only after an Olympic skating champion moved to Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel that the sport literally took off.

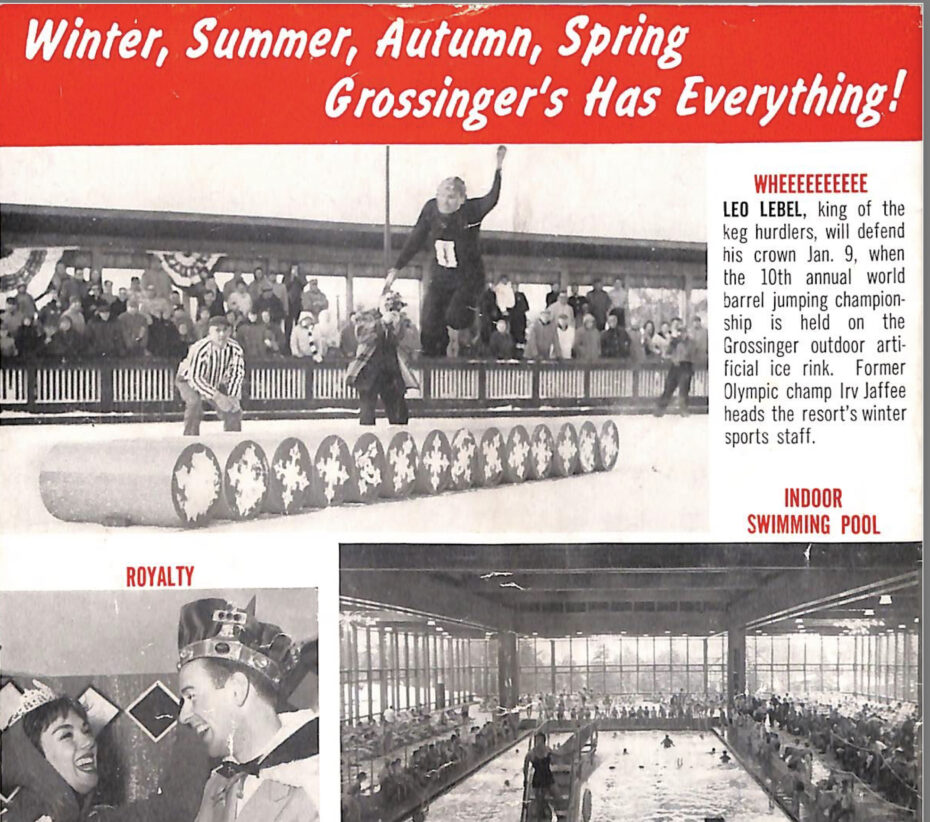

American speed skater Irving Jaffee had won two gold medals at the 1932 Winter Olympics, when two years later found himself employed at Grossinger’s as their winter sports director. Looking to inject some fun and spectacle into their winter programme Jaffee hit upon hosting a world championship for barrel jumping. Using his fame as an Olympic champion and Grossinger’s superb outdoor ice rink, competitive barrel jumping swiftly became a big draw at the popular holiday resort, and the perilous sports blossomed.

Grossinger’s would host the championship for the next quarter of a century, and it became a staple on ABC’s Wide World of Sports television programme. “I won two Olympic gold medals as a speed skater, both in 1932, and I’ve played some hockey,” explained Jaffee to Sports Illustrated in 1961, “but I’d never have the guts to try barrel jumping.”

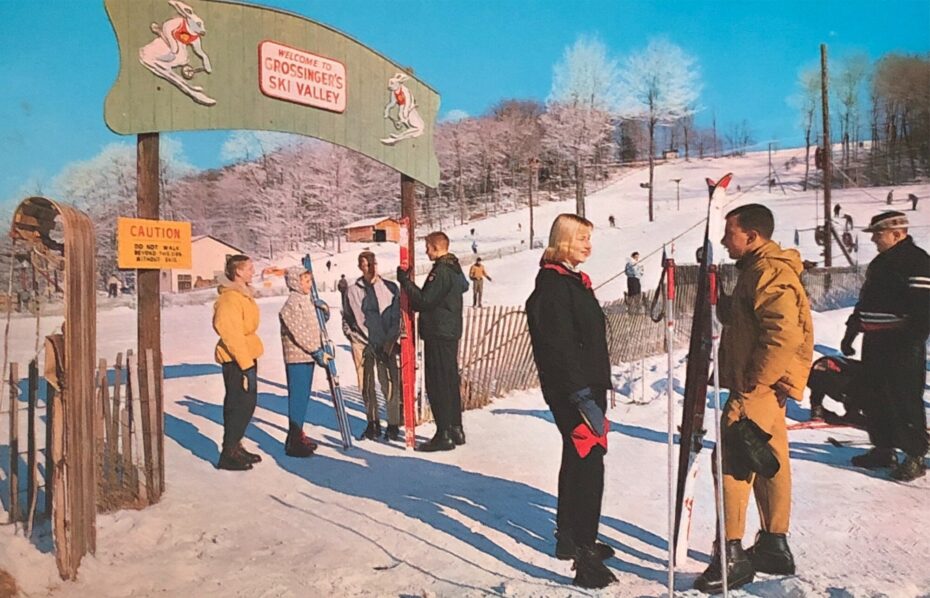

The name of Grossinger’s Catskill Resort may have faded into memory, but it was once a byword for luxurious recreation. Located two hours north of Manhattan, Grossinger’s was the jewel of what was once known as the ‘Borscht Belt’, a concentration of resorts, hotels and holiday camping grounds that catered to mostly Jewish affluent New Yorkers.

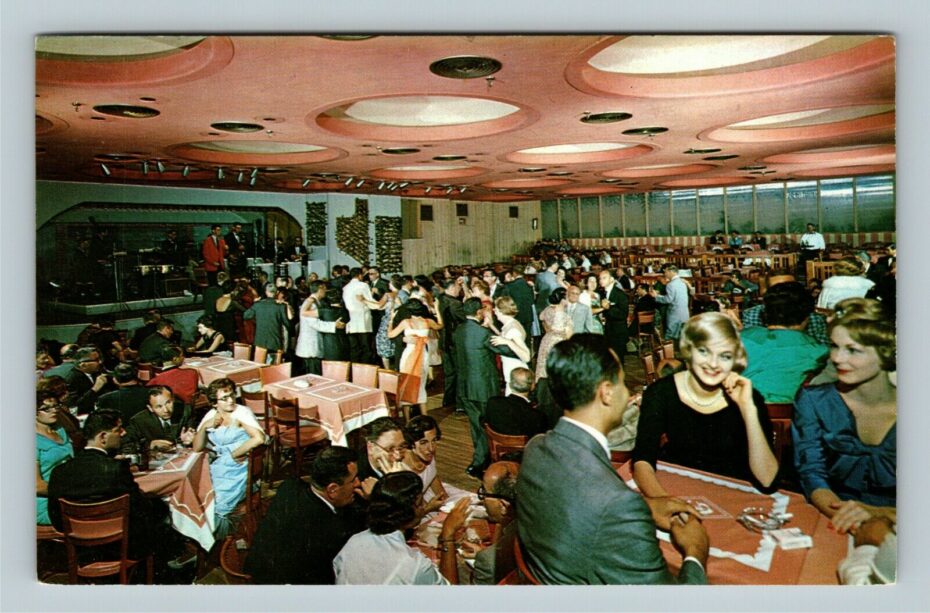

Overseen by Jenny Grossinger, the resort was spectacular: three swimming pools, grand ballrooms, a dining room large enough to seat 1,700, and nightclubs such as the Terrace Room and glitzy Pink Elephant, that played host to the likes of Mel Brooks, Jack Benny and Milton Berle. At its heyday in the 1950s, over 150,000 pleasure seekers were coming to Grossinger’s every year. No wonder one review in 1954 described Grossinger’s as, “to resort hotels as Bergdorf Goodman is to department stores, Cadillac to cars, and mink to furs.”

The winter season was as popular as the summer, with skiing in the surrounding Catskill Mountains on offer, as well as Grossinger’s own outdoor ice rink. And one of the highlights of the winter programme was the annual barrel jumping competition; after all, what could be more entertaining than watching ice skaters breathlessly launching themselves at high speeds through the air, before crashing spectacularly into barrels, ice or the rink itself to the cheers of the spectators.

As Sports Illustrated reported one winter, “Some skaters did belly whoppers at 30 and 40 mph, one crashing head-first into the row of barrels. They tumbled wildly, gasped for breath after the wind had been knocked out of them and then wiggle-wobbled back to the bench to await their next turn.”

The first true great competitive barrel jumper was Edmund Lamy. Born in 1891, Lamy dominated speed skating, the reigning American champion both indoors and out in 1908, 1909 and 1910. Sporting a dashing red skate suit, Lamy was known as the ‘Red Demon’. He was also a spectacular barrel jumper. As one contemporary newspaper reported, Lamy was, “perhaps the greatest skater ever to don a pair of long blades. He consistently beat the class of international competition from the time he was fourteen. His prowess as a barrel jumper is legendary with and his record for the fastest five miles on a curved track still stands unchallenged.’ At Saranac Lake in New York, 1925, Lamy flew through the air over fourteen barrels, then a record.

In the heyday of the sport’s popularity being held at Grossinger’s, the kings of the keg hurdlers were the LeBel brothers. In 1960, Leo LeBel a 29 year old student at the University of Hartford, Connecticut won his sixth consecutive championship at Grossinger’s, his winning leap clocking in at an astonishing 26 feet 2 1/2 inches, clearing sixteen barrels. The mid to late sixties were dominated by Ken LeBel, North American Indoor and Outdoor speed skating champion, member of the 1963 World Hockey Team, and winner of three barrel jumping championships. Competition in 1966 was fierce when Sports Illustrated was again on hand to witness the competition:

“One by one the contestants were eliminated, until only Ken LeBel, Jacques St. Pierre—who had gone to bed at 10 the night before and had lain awake worrying until 3 a.m.—and Richard Widmark were left. Widmark, in his three tries at 16 barrels , went clunk, splat and whomp, and tottered away as if he had been creamed by a linebacker.

Now it was LeBel against St. Pierre. The yellow 17th barrel was set in line. If neither cleared that barrel, the victory would go to St. Pierre, who had leaped 28 feet 3¼ inches. LeBel’s longest jump was 27 feet, and he had torn a stomach muscle in the process. St. Pierre failed in three tries at 17 barrels, and now it came down to one last jump for LeBel.

Slowly LeBel skated around the blue-tinted ice. He stopped to stare at the long row of barrels, then skated away, churning up more and more speed with each stride as he circled the rink once, then twice. He flashed around the final curve, angled toward the barrels, then pumped his arms for the lift-off. He rose and flew—over all the barrels but one. LeBel thudded to the ice, a black streak skidding and skittering out of control, until he came to an inglorious rest against the barricade of mattresses. St. Pierre turned down the winner’s purse because he wanted to retain his amateur status. He accepted a trophy instead and a kiss from French Actress Françoise Hardy.”

By the 1980s, the popularity of the Borscht Belt had declined. Cheaper airfares saw holiday makers venture further afield than New York’s Catskill mountains. In 1985 Grossinger’s posted a $1.8 million loss and their illustrious doors closed soon after. And with its main host gone, the annual barrel jumping World Championship sadly soon all but disappeared into obscurity. Today it is still possible to come across ruins of abandoned Borscht Belt resorts in the Catskills.

Until it was recently demolished, you could wander through Jenny Grossinger’s vast pleasure palace, through corridors of empty hotel rooms, crumbling swimming pools and tennis courts, and decaying ballrooms and bars, the sounds of holiday makers, cha-cha bands and the tinkling of cocktail glasses long since vanished.

Of all abandoned spaces, perhaps none are quite as poignant as the ruins of a sporting venue. Stepping through the doors of the empty ice skate house, past the left behind scoreboard of the North American Invitational Barrel Jumping competition, you find yourself standing on the ruins of the outdoor ice rink, now covered with weeds. Where spectators once roared on their favourite speeding daredevils as they bravely flung themselves over the ice with the hopes of a safe landing and a chance at the cup, there is now only silence.