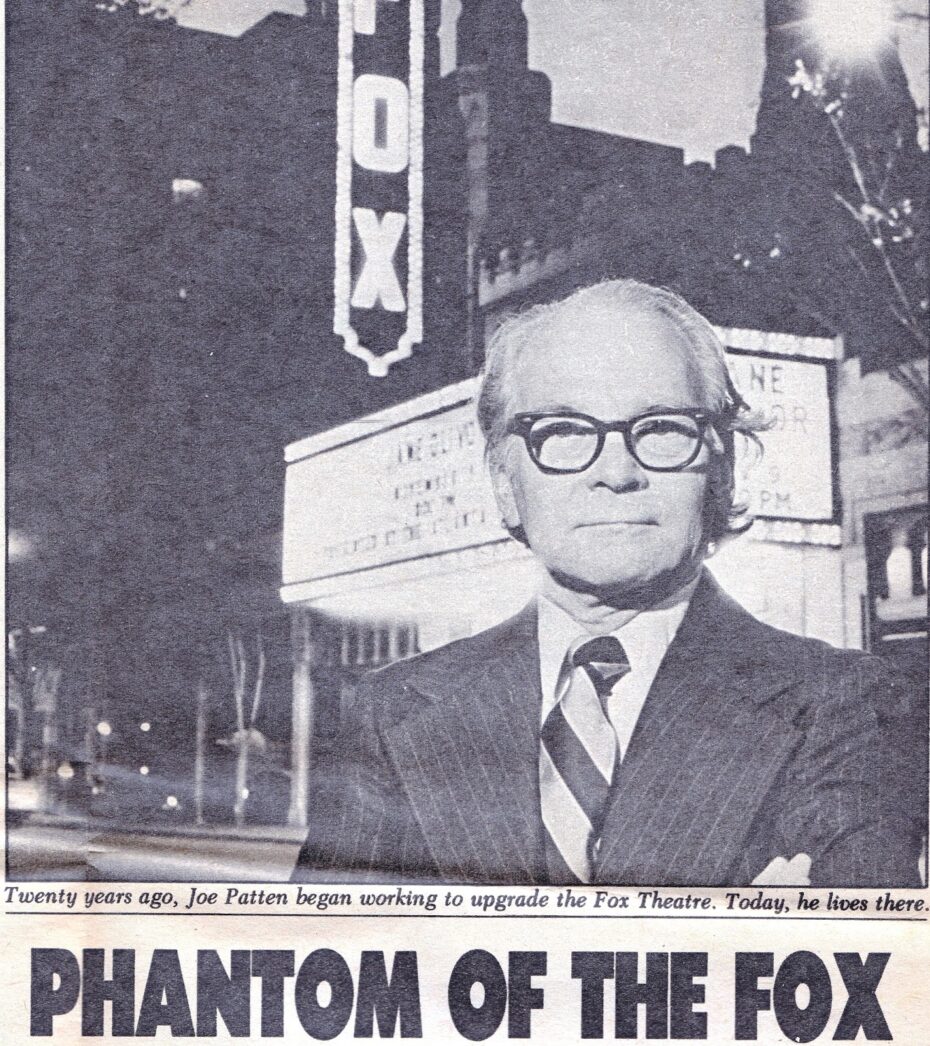

Theatres are inherently haunted places. By night, actors tread the boards, conjuring the spirits of those who lived and those who never were. We can hardly expect all those shades to simply evaporate into the ether after the final curtain. Instead they seep into dark and secluded backstage corners – an underground lake, perhaps – and into our imaginations, held at bay only by a “ghost light” casting its lonely glow on the empty stage long after everyone else has stumbled home to their beds. But some phantoms are more than mere superstition. For 36 years a benevolent spirit of flesh and blood haunted Atlanta’s famed Fabulous Fox Theatre, living in a lavish secret apartment underneath the building’s iconic Moorish dome. While Paris’s (semi) fictional Phantom of the Opera unleashed havoc on the Opera Garnier, dropping chandeliers and generally running amok among both the rigging and the chorus girls, the ghost who inhabited the Fox saved his theatre from ruin twice. His name was Joe Patten, but Atlanta knew him as their beloved Phantom of the Fox.

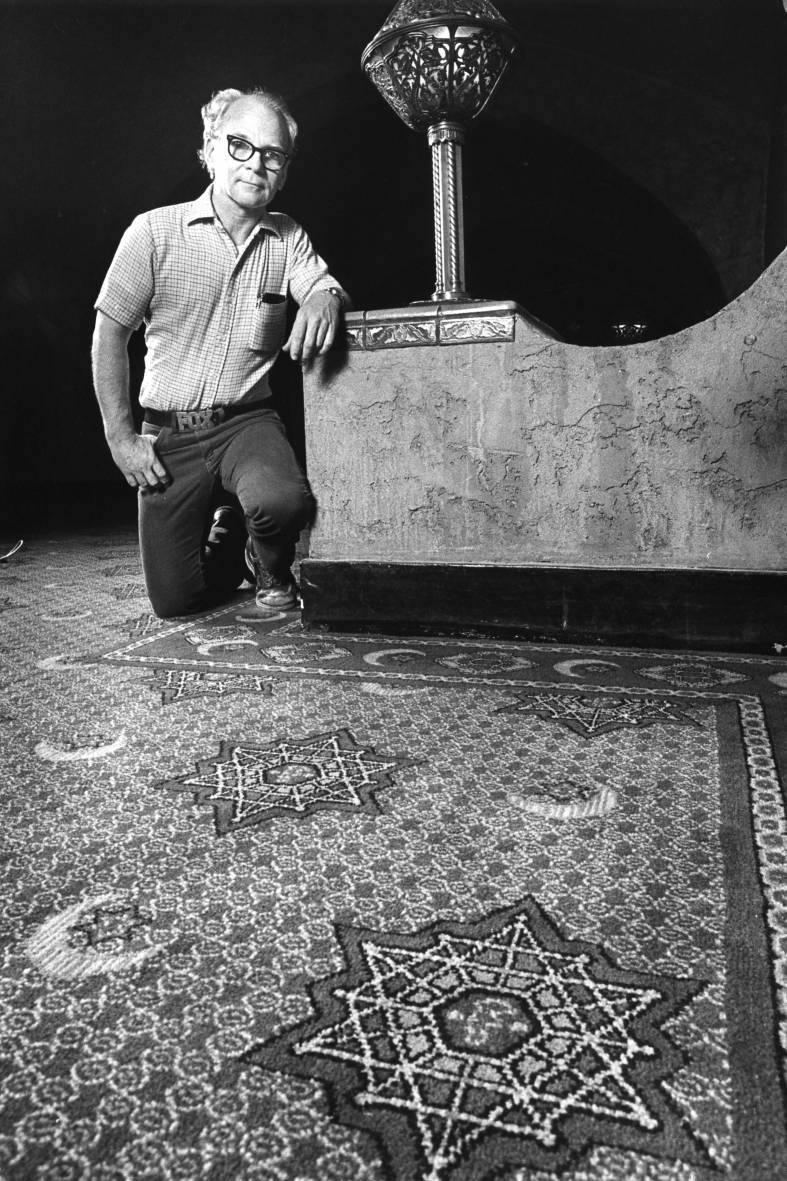

You could say Patten and the Fox grew up together; he was only a year old when, in 1928, the Shriners broke ground on what was meant to be their grand Atlanta headquarters at the corner of Ponce de Leon Avenue and Peachtree Street. The Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine was founded in 1870 by a group of Freemasons inspired by the exotic glamour of a party hosted by an Arabian diplomat. The fraternity incorporated Middle Eastern and North African symbols into their rituals and iconography and adopted the red fez as their official regalia. So, fittingly, the Atlanta Shriners drew inspiration from the Alhambra and the Temple of Karnak when designing their fantastical temple.

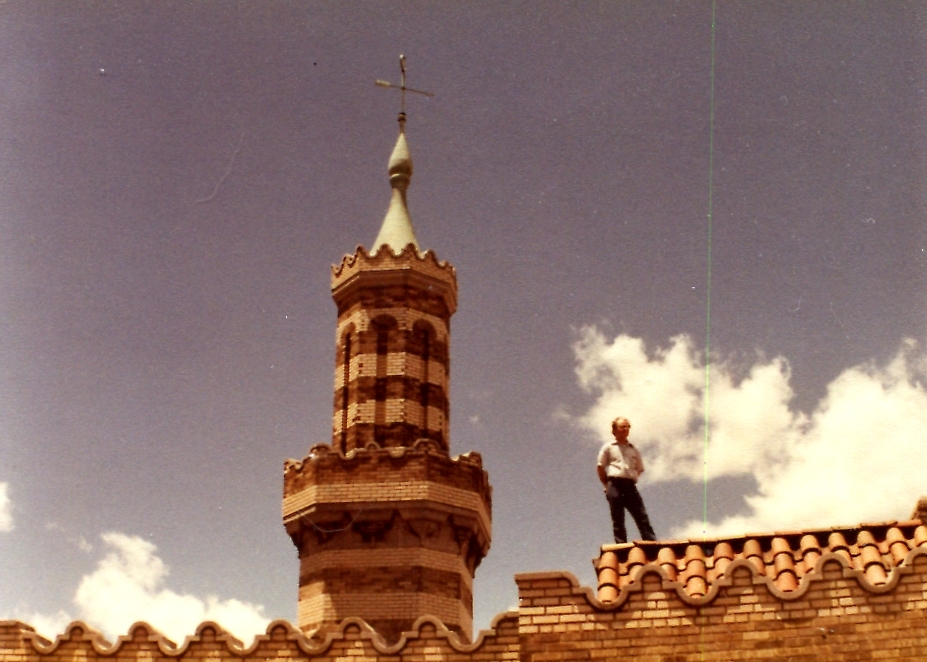

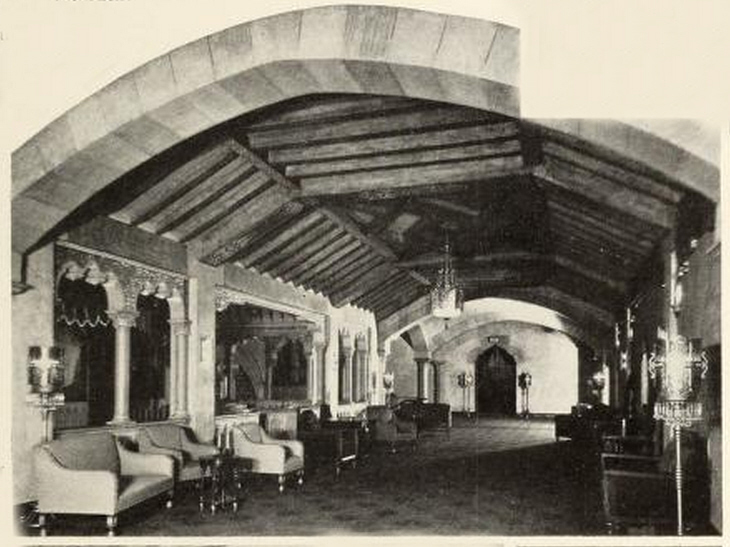

As a roofline studded with soaring minarets and onion domes rose over Midtown, the budget for building such a wonder mounted as well. The Shriners found themselves in need of funds, so they turned to movie mogul William Fox and his growing empire of movie palaces. Fox agreed to help fund the staggering $3 million project ($40 million in today’s dollars), and the grand auditorium became a movie theatre like no other. Under a ceiling spangled with crystal stars and projected clouds, theatregoers entered a magnificent tented bazaar with the fortress-like walls of the medina surrounding the auditorium’s 4,665 seats. The proscenium was draped in oriental carpets and lit with shimmering filigree lanterns, while the balcony was crowned by a trompe l’oeil desert tent festooned with richly gathered fabric and tassels. The crowning detail taking the auditorium from a Shriners meeting place to iconic movie palace was the addition of a custom-built, 3,622-pipe Möller organ that rises from the orchestra pit. Still the second largest theatre organ in the world, outpaced only by the one at Radio City Music Hall in New York City, “Mighty Mo” delighted audiences during singalongs and silent movies alike.

This glittering world of lotus-topped columns and gilded arabesque archways opened on Christmas Day 1929, just two months after the stock market crash plunged the U.S. into the Great Depression. But you wouldn’t have guessed at the country’s dire economic situation by the patrons lined up around the block to see a sold-out opening bill that included Steamboat Willie, Walt Disney’s first Mickey Mouse cartoon.

But neither the Shriners nor the movie magnate and his empire could outlast the Depression. Three years after the magnificent theatre’s debut, the mortgage was foreclosed, and the Fox was auctioned on Atlanta’s courthouse steps for just $75,000. The name on the deed didn’t seem to matter to Atlantans who continued to flock to the Fox for a few hours’ respite from their hardships, a chance to escape into a film-based fantasyland punctuated by the sound of a pipe organ.

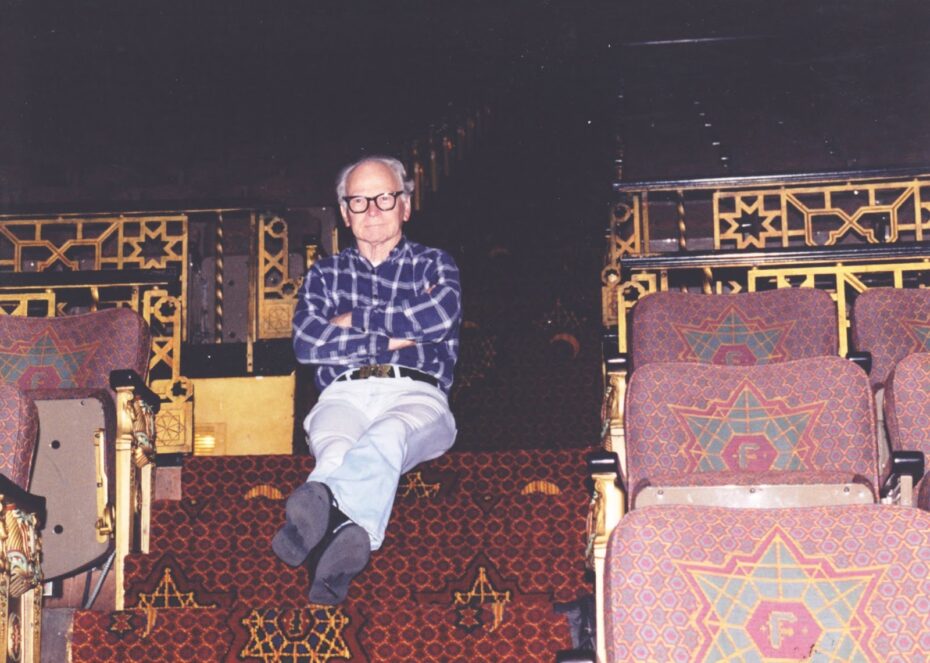

Mighty Mo’s deep bellow was what first drew Patten to the Fox during a visit to Atlanta in 1947. A free matinee of the Atlanta Pops Orchestra on the Fourth of July gave Patten his first glimpse of the theatre’s splendour, and it was the start of a lifelong love. “We sat in the balcony, but we could see the blue sky and the twinkling stars and the moving clouds,” he told Atlanta magazine in 2002. “It was an experience I couldn’t believe.”

Patten, who grew up in Lakeland, Florida, developed a passion for pipe organs as a child and was apprenticed to his church’s organ repairman at the age of 12. After World War II, he worked as an X-ray technician, traveling to install and repair systems at major hospitals while continuing to practice his hobby of restoring organs. In 1963 he settled in Atlanta.

Though the Fox thrived through the 30s, 40s and 50s, hosting not only movies but live performances as well, post-War white flight sent Atlanta into economic decline and the Fox into squalor. By the time Patten moved to the city, the Fox had been reduced to playing second-run movies to half empty seats as the middle-class crowds left for the suburbs and modern multiplexes. Mighty Mo, too, crumbled into disrepair, reduced only to exasperated groans.

Patten approached the theater management with a deal: if they would provide the materials, he would repair the organ for free. He spent 10 months lovingly coaxing Mighty Mo back to life, cleaning away the decades of dirt that had caused ciphers, a malfunction in which pipes continue to sound after a key is released. On Thanksgiving Day 1963, Mighty Mo sang for an audience once more.

While he resuscitated the neglected organ, Patten also explored the Fox’s labyrinthine inner world, befriending the other people who worked behind the scenes and learning every vital system, every hidden passage. From working the stage ballasts to raise and lower the curtain to running the heating plant and changing the lightbulbs that created the mesmerizing night sky over the stage, Patten memorized all of the Fox’s secrets. Like Gaston Leroux’s Phantom, Patten could seemingly walk through the walls of his theatrical domain, disappearing in one place only to reappear as if by magic elsewhere. He became a fierce protector of the theatre. After once discovering a group of scavengers attempting to make off with a truckload of stolen furniture, Patten and his friends removed every antique not bolted in place into a tucked away corner of the basement to which he possessed the only key.

But thieves were easy foes compared to the corporate threat the Fox faced in 1974. The grand box office had already been shuttered, presumably for good, when telephone giant Southern Bell purchased the aging Fox for its prime Peachtree Street location and planned to demolish the entire thing. Patten rallied to the theatre’s defense, spearheading the creation of the nonprofit Atlanta Landmarks to save it from the wrecking ball. And Patten was not alone in his passion.

The people of Atlanta refused to see their Midtown minarets razed for a corporate parking lot, and soon the Save the Fox campaign ignited into a furor. Benefit concerts from rock legends like Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers Band combined with other fundraisers and individual donations raised nearly $2 million. Amidst the public relations nightmare–thousands of Southern Bell customers sent back their monthly bills emblazoned with the words “Save the Fox” – the company sold the building to Atlanta Landmarks. The Fox was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

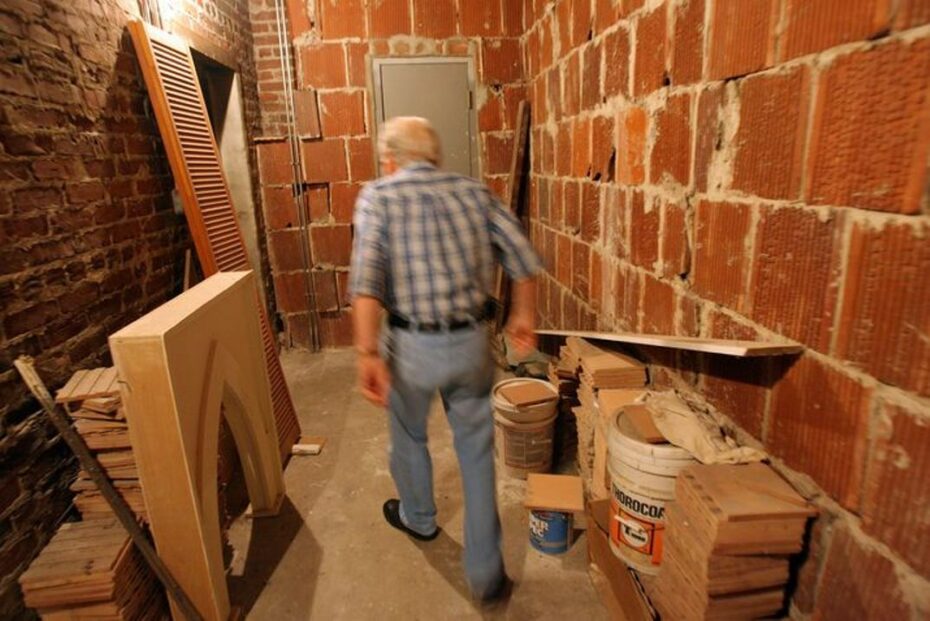

Restoration ensued, with Patten firmly installed as technical director. He was already spending 80 hours a week caring for the building when the Atlanta Landmarks board of directors approached him with an idea. The Fox needed round-the-clock care, someone to watch over her and tend to any emergencies, someone who knew each and every corner and passage. And so the Phantom moved into the Fox. Patten selected the old executive offices of the Shriners, by that point disused and plagued by persistent leaks from the rooftop domes, as the site for his new apartment. While he paid for the $100,000 construction out of his own pocket, Atlanta Landmarks granted him a lifetime, rent-free lease.

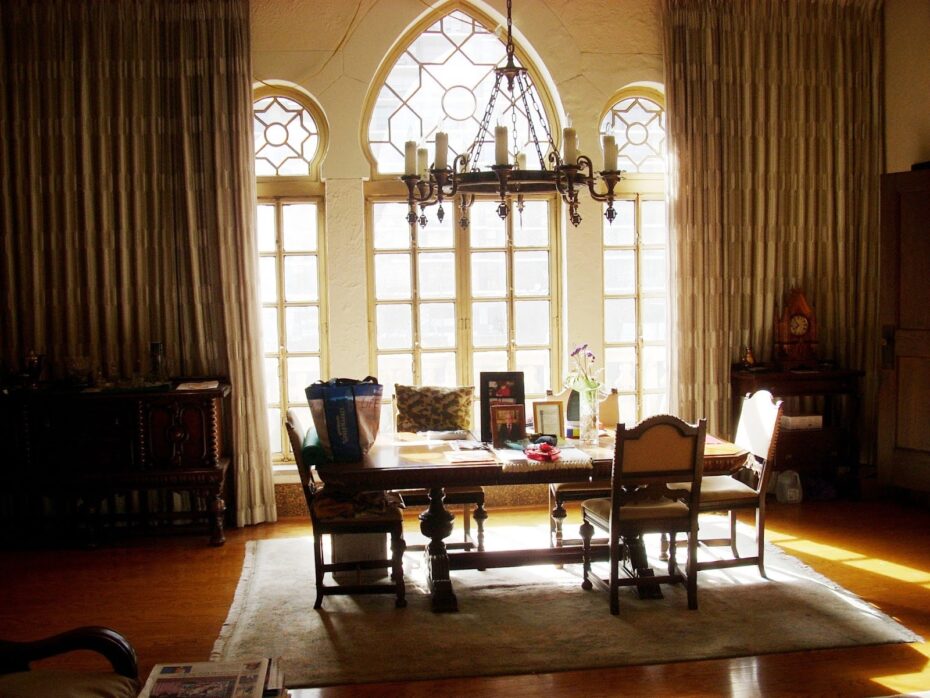

This hidden home, tucked away unseen by the thousands of theatregoers attending shows, concerts and ballets each year, featured grand star-topped windows and Moorish arches much like the public areas of the theatre. It was a space full of just the kind of delightful secrets one might hope to find behind one of the dozens of unmarked doors inside a historic theatre. Stained glass windows and a newly-designed fountain made to match the grand designs below greeted guests lucky enough to be invited into Patten’s personal lair. A shallow balcony offered views of Ponce de Leon Avenue, and the apartment had its own clandestine entrance from the street. Another secret door gave the Phantom access to the very top of the theatre’s balcony so he could take in a show or listen to Mighty Mo any time he liked. Patten reportedly slid down the auditorium’s banisters on occasion, after all the patrons had gone for the night.

Patten filled his grand, three-story apartment with antiques, including a player piano for which he owned hundreds of scrolls and a wine rack made from the 19th-century safe from a defunct department store down the street. The fulfilment of every book-lover’s dream, a custom-built, hinged bookshelf on wheels concealed a closet beyond.

Patten played host to everyone from Elizabeth Taylor to David Copperfield when they made appearances at the Fox. He took comic and fellow classic car aficionado Jay Leno for a joy ride through the streets of Atlanta in his 1937 Rolls Royce Phantom III, one of many among his collection of rare automobiles which he tended as carefully as he did the Fox’s mighty organ. When the Rolling Stones played the Fox, it was Patten who escorted them safely out a side door to escape the crush of screaming fans.

In the early hours of an April morning in 1996, Patten was awakened by the blaring of an alarm. A restaurant adjacent to the Fox had caught fire, and the resulting blaze was threatening the theatre. Smoke billowed from the roof as flames from the four-alarm fire licked at the fire wall between the two buildings. Patten summoned the fire department, and, with his vast knowledge of the building’s passages and architecture, was able to direct them to the best place to tackle the flames. While some of the Fox’s administrative offices were damaged, the building survived with no harm to the theatre. The evening’s performance went on as scheduled, and Patten had once again proven himself the Fox’s most loyal guardian.

Soon, though, the relationship between Patten and theatre management would sour. In 2010, hours after returning home from a hospital stay, the then-83-year-old Patten received a letter from Atlanta Landmarks suggesting he “seek out an assisted-living residence.” The letter further claimed that Fox staff could not be expected to check on or care for him as he aged and his health declined. “To burden the staff with this future expectation cannot be presumed or continued, as it is both unfair to them and affects the Theatre’s operations.” Patten balked and refused, but a clause in his original lease allowed revisions of the document with a two-thirds vote of the board. The measure passed, and Atlanta Landmarks insisted Patten sign a new lease stipulating he could stay in his home only as long as he was able to care for himself without assistance. Adding insult to injury, the new lease also stated Patten must ask the board’s permission for any house guests. Theatre officials claimed they were motivated solely by concern for Patten’s health and well-being, but Patten’s friends worried he was being ousted for access to the valuable space he occupied.

Just as the people of Atlanta had rallied with Patten to save the Fox, now they rallied for him to stay right where they felt he belonged: at home in his secret Fox apartment. Protests against management mounted on the streets outside the theatre and online as Patten filed a lawsuit alleging housing discrimination. The suit was settled out of court in 2010, and Patten was allowed to remain in his home under the terms of his original lifetime lease. However, Fox management reportedly did restrict his former free access to the rest of the building.

Patten’s closest allies repeatedly said that he hoped to die in the theatre to which he gave nearly 40 years of his life. One-time Fox organist Bob Van Camp said of his perpetual-bachelor friend in an Atlanta Journal-Constitution profile, “The Fox is Mrs. Joe Patten. Joe is married to that theatre.” While he always chuckled demurely at the moniker he earned, Patten did think Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera was the best and most fitting show the Fox ever hosted. In 2016, at the age of 89, Patten suffered a stroke and was taken to Emory Hospital at Midtown, walking distance from his theatre home. A spokesperson for his family said Patten died listening to his favourite organ music.

If ghosts of the non-corporeal variety are real, it’s tempting to hope that Patten remains ever watchful of the Fabulous Fox even from beyond, lovingly guarding her secrets and perhaps whooshing down the occasional banister, leaving just a whisper and a chill in his wake. In January 2020, the Fox (still headed by the same board members involved in Patten’s attempted eviction) filed building permits with the city to return Patten’s former apartment to office space and storage, as though the Phantom had never really existed at all.