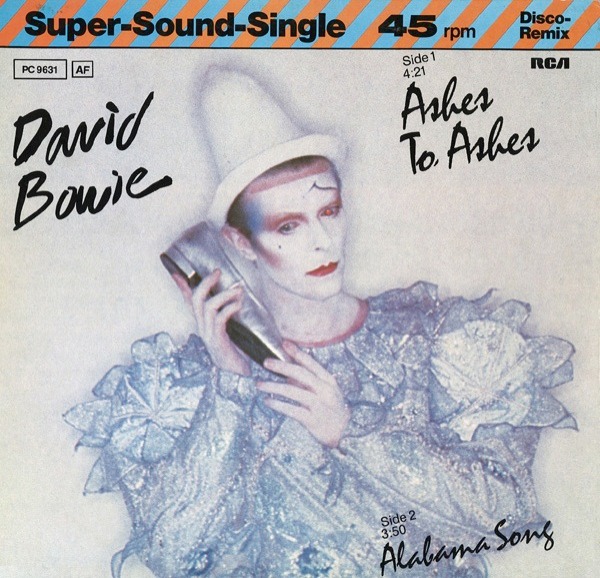

“I’m Pierrot,” once said the late, great David Bowie: “I’m Everyman”. We all know his face: white like the moon, his only friend, with sad black lines drawn around the eyes, smudged by a teardrop or two. He’s dressed in an oversized white shirt with ruffles and pompoms and a little white pointed hat. Pierrot is the archetype of the sad clown but he’s also the father of mime, an alter ego for the Decadent, Symbolist, and Modernist movements, and a muse for artists, poets, and designers. But who is Pierrot? Where did he come from? From being the laughing stock of seventeenth-century comedy into the brooding romanticism of the fin de siècle, it’s time to uncover the history of Pierrot, an icon with many faces.

The Pierrot we recognise today was born on the stage as a lovechild of the Italian commedia dell’arte and French playwright Molière’s imagination. The story begins in 17th century France in the Palais-Royal theatre in Paris. Molière wrote a character with the name Pierrot into his five-act comedy Don Juan or the Feast of the Stone as a peasant with a bit part in the play’s second act, giving this proto-Pierrot his theatre debut. Perhaps Pierrot would have remained just another character in a Molière play had the playwright not shared the venue with a troupe of commedia dell’arte performers from Italy.

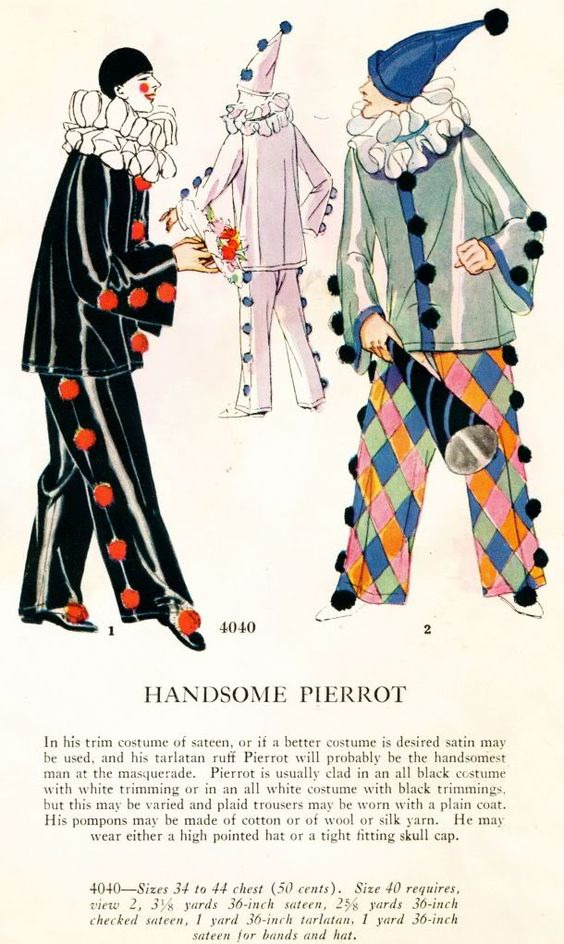

The commedia dell’arte, the ancestor of poop jokes and slapstick, paraded its stock characters parodying regions and figures from Italy in a cast of archetypes. The Pierrot of the commedia dell’arte was not the sophisticated and melancholy clown we see crying on chocolate boxes but rather a bumbling fool portrayed purely for comedic purposes. He was the butt of the jokes with his unrequited love for Columbine, who chose the rakish and witty Harlequin in his chequered costume instead. When Italian comic theatre was expelled by the French at the end of the 17th century for planning to perform an offensive play, Pierrot’s character took on a new lease of life and was already part of their repertoire.

Even in these early stages of Pierrot’s life in the commedia dell’arte, some could see his sensitive side lying beneath, like Rococo French artist Jean-Antoine Watteau who painted sympathetic depictions of Pierrot that humanised his rejection and loneliness. However, it was really in the 1800s that Pierrot shed his old skin of the bumbling fool and slipped into a new one befitting a melancholy artistic muse, thanks to Bohemian mime Jean-Gaspard Deburau.

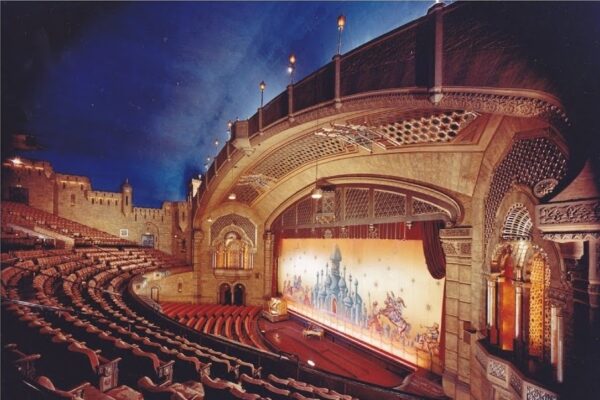

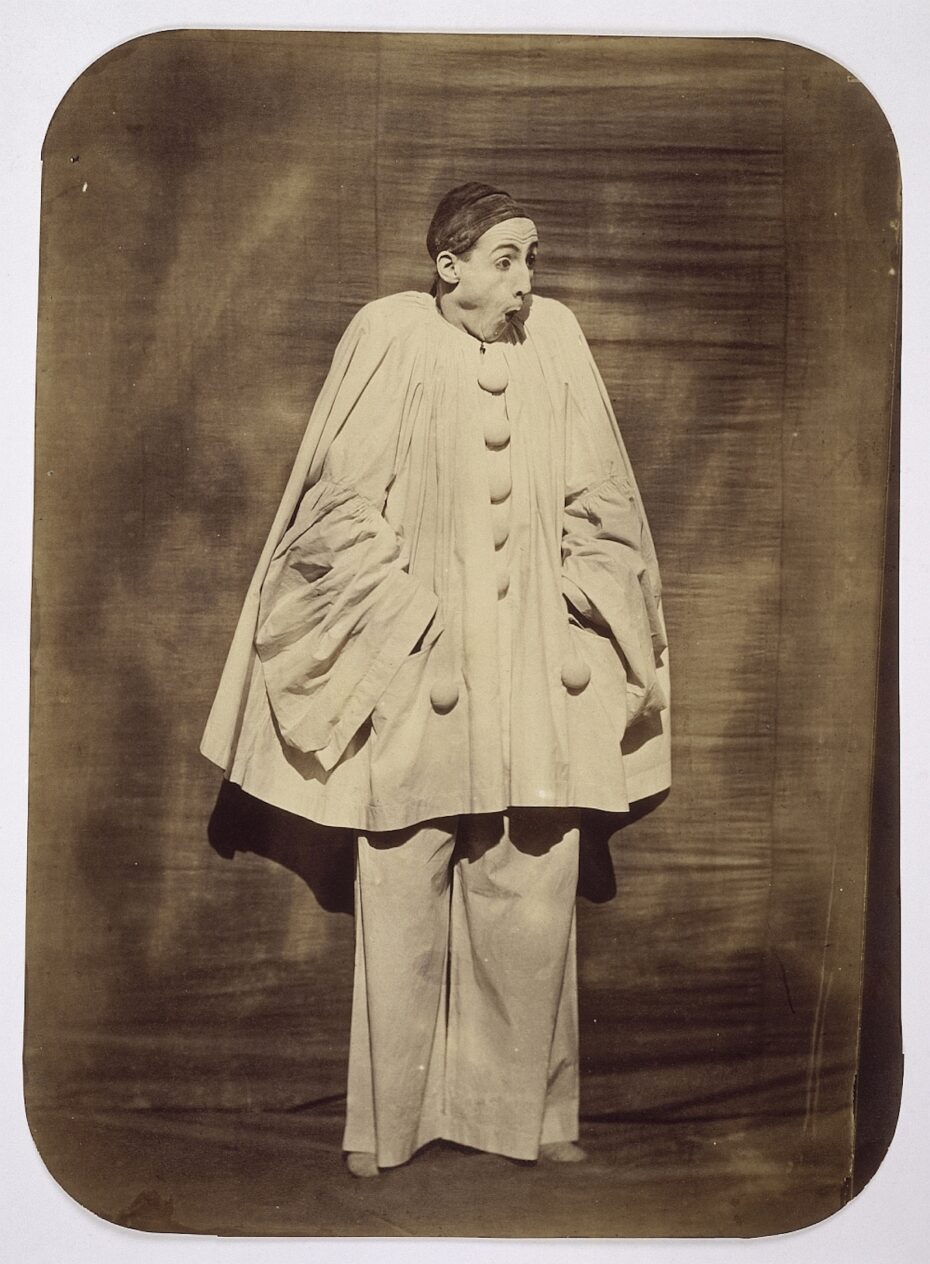

Deburau moved from his home in what is the Czech Republic today to Paris and performed under the name Baptiste at the Théȃtre des Funambules on the infamous Boulevard du Crime, a riotous theatre district now lost in time, once known for its abundance of crime dramas showing. But the Théȃtre des Funambules mostly wowed its spectators with mimes and acrobats, and here, Deburau became a legend by performing as Pierrot, a role he would carry with him until his death in 1846. Deburau gave Pierrot his own twist and interpretation of the clown with a delicate and nuanced sense of tragedy and longing.

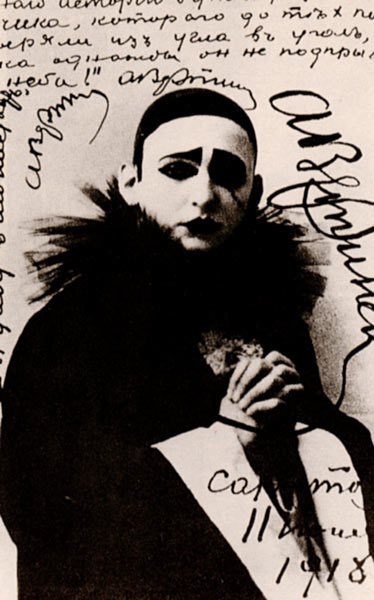

This new incarnation of Pierrot as a melancholic figure in mime form defines what we think of the classic French mime today: white-faced, black tears streaming down sad, expressive eyes. Deburau’s son and other famous mimes from Paul Legrand to David Bowie (but more on him later) continued depicting Pierrot as the heartbroken, tortured artist.

In the late 1800s, the French Romanticist poet Théophile Gautier wrote a comedic fantasy, Pierrot Posthume, featuring the famous clown, elevating Pierrot into the literary circle. There was even a theatrical society founded by an impressive coterie of writers and artists from the Decadence movement, that gave Pierrot’s character a darker twist, depicting him in several works as a savage dandy and a murderous arsonist.

Stripped of his innocence by the Decadents, the fearless illustrator Aubrey Beardsley was inspired to adopt Pierrot as his muse during Britain’s counterpart movement, Aestheticism. A former stock character turned disillusioned foe of idealism, he became a popular vessel for artists of the era.

Pierrot continued to weave his mysterious way from one artistic movement to another by seeping into the poetry of the Symbolists, who found him to be a fitting mascot to represent absolute truths symbolically through metaphorical images and language. Notable symbolist poets like Paul Verlaine, Albert Giraud and Jules Laforgue, exploring Pierrot and his relationship with the moon. (Laforgue’s work went on to inspire T.S. Eliot). Through the Decadents and the Symbolists, Pierrot well and truly abandoned his foolish persona behind him and evolved into a figurehead for the poète maudit –a poet living on the fringes or outside society – in the fin de siècle.

To the Modernists, he was a silent, alienated observer pondering the mysteries of the human condition. He was the artistic muse to post-impressionists like Seurat (Pierrot with a White Pipe, 1883) and Cézanne’s Pierrot and Harlequin (1888), a painting noted for being filled with suppressed emotion, all the way to Pablo Picasso’s early work in his depiction of Pierrot and Columbine (1900) and cubist Juan Gris Pierrot with Book (1924).

Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg helped cement Pierrot’s legacy into music by setting Albert Giraud poems to his avant-garde melodrama Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21. It captured the spirit of the age, where our beloved and familiar clown moves through a nightmarish world plagued with desire, violence, sacrilege, and grotesque nostalgia. In 1996, Icelandic avant-garde pop singer Björk performed an ephemeral and unrecorded rendition of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire at the Verbier Festival.

And then of course there was David Bowie, who studied avant-garde theatre, mime, and the commedia dell’arte under Lindsay Kemp. He was not just intimate with Pierrot both as a comedic and sad figure, but Bowie also made his theatrical debut in Pierrot in Turquoise at the New Theatre in Oxford in 1967. He would revisit his legendary muse from the commedia dell’arte in 1980 in his song Ashes to Ashes and its accompanying hallucinogenic music video playing the sad clown himself.

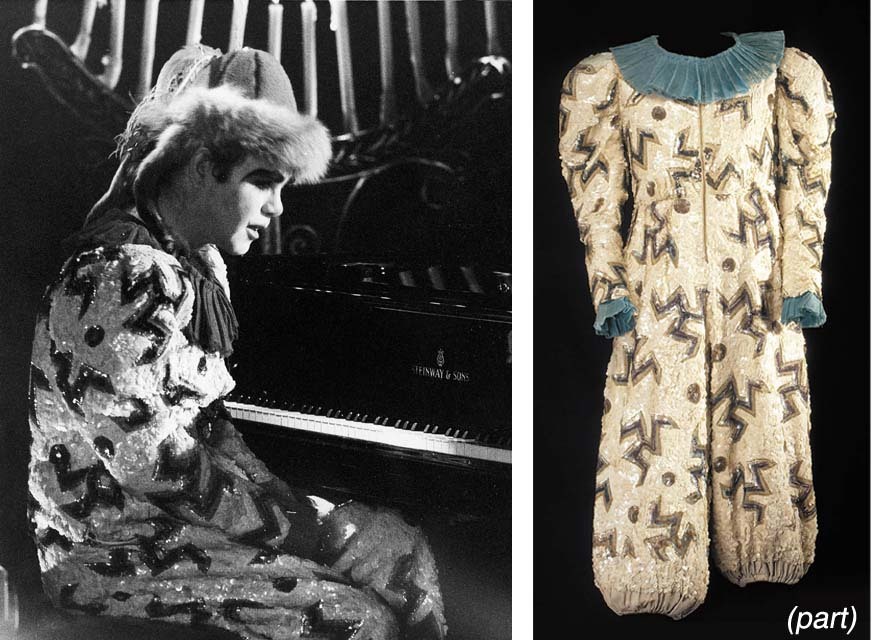

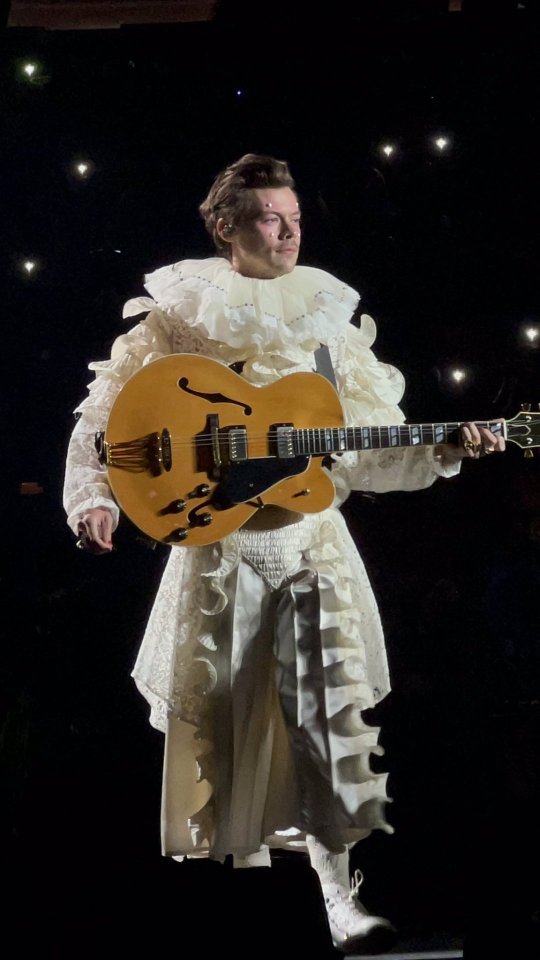

Elton John too transformed into Pierrot for his ‘Cry To Heaven’ music video, 1985, and most recently, superstar Harry Styles adopted the iconic costume on his tour.

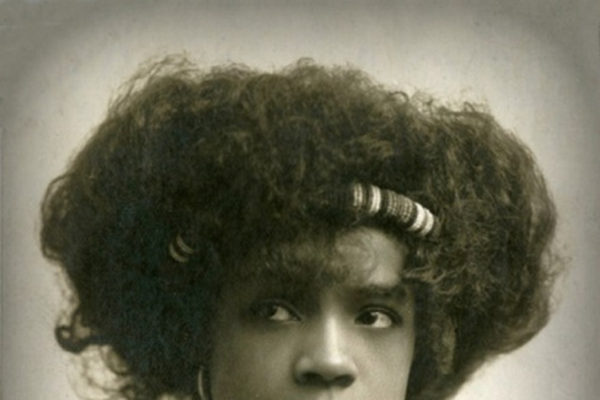

Although Pierrot was a poet’s and artist’s muse, he became a commercial figure too. He not only appeared on the side bonbon boxes and as melancholic porcelain figures in department store displays, but one day, female figurines of the sad clown, Pierrette, also appeared. From the late 19th century onwards, Pierrot finally conquered women.

Rather than winning the love of Columbine or another maiden, women wanted to be him. Adventurous and rebellious women throughout recent history found themselves attracted to embodying Pierrot, and he would even become a fashion icon.

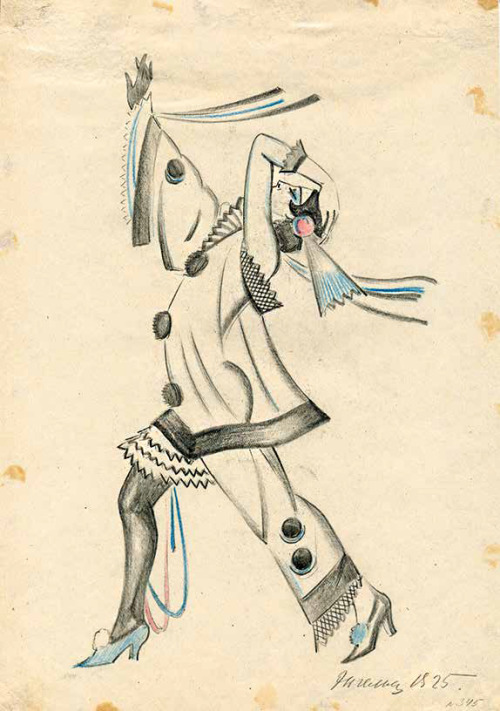

The silhouette of Pierrot is somewhat androgynous, which appealed to the fashion of the 1920s and continues to inspire artists, designers, fashion icons (Twiggy performed as Pierrot in The Boy Friend in 1971) and rockstars and performers alike.

Ever the chameleon, shapeshifting into an icon fitting the current Zeitgeist, it seems we can all find something to relate to in Pierrot.