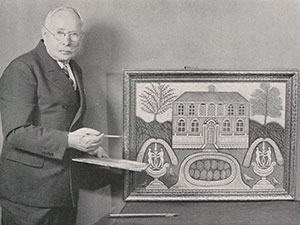

New York, 1942 – with Morris Hirshfield’s painting Nude at the Window (1941)

at Peggy Guggenheim’s town-house photographed by Hermann Landshoff

In 1943, the New York art world was abuzz about a new exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The esteemed institution was hosting a show featuring one Morris Hirshfield, an immigrant who had found success as a tailor and then shoe designer before becoming a self-taught artist. His work was praised by the leading Surrealists and major art patrons of the time (see André Breton, Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and Leonora Carrington pictured gazing at his painting inside Peggy Guggenheim‘s New York townhouse in 1942). But Hirshfield’s “outsider” style was maybe just a bit too outsider for the city’s elite at the time; the exhibit was on the receiving end of such negative press and critique that the museum’s director was ultimately fired. Some 80 years later, his paintings have finally been dusted off and placed back in the spotlight.

No one would have guessed that Morris Hirshfield would have become an artist praised even by the leading Surrealists and major art patrons. He was born in Poland in 1872 and emigrated to the United States at age 18 with his family, seeking a better life. The Jewish Hirshfield changed his first name from Moishe to Morris and became a pattern cutter in a women’s suit and cloak factory located downtown. He climbed the career ladder to become a tailor and along with his brother, started a women’s clothing shop. He had always had a creative bent, making religious sculptures out of wood, but at first chose a more traditional path.

His artistic talent was seen in the colourful slippers he designed when he opened the E-Z Walk Manufacturing company in 1912. While they originally started by making orthopaedic devices, they found more success in their boudoir slippers, featuring a wool felt base decked out with silk velvet and mohair trim, pompoms, glass beads and fabric flowers.

Even during the Great Depression, E-Z Walk raked in a million annually. But due to health issues, Hirshfield was forced to retire in 1935. He and his wife soon downsized to a one-bedroom apartment and Hirshfield even tried his hand at being a “foot appliance consultant” (we tried, and failed, to clarify what that is). He eventualy turned to another creative pursuit, painting, so impoverished that he began his first works by layering paint on top of existing canvases.

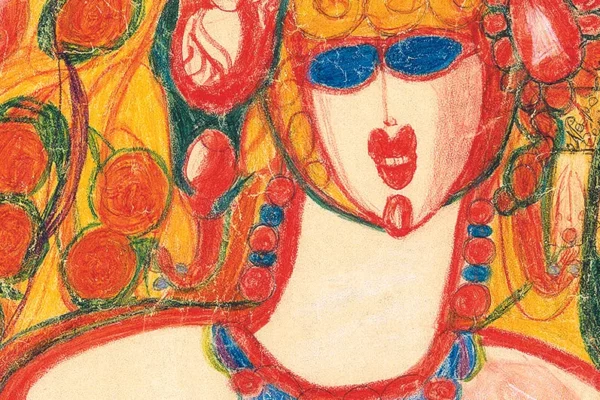

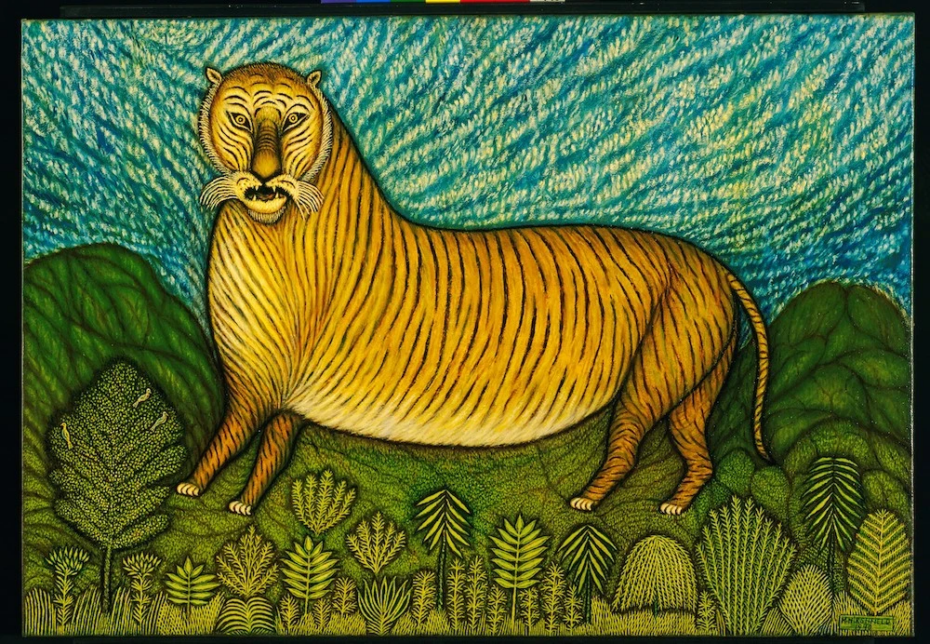

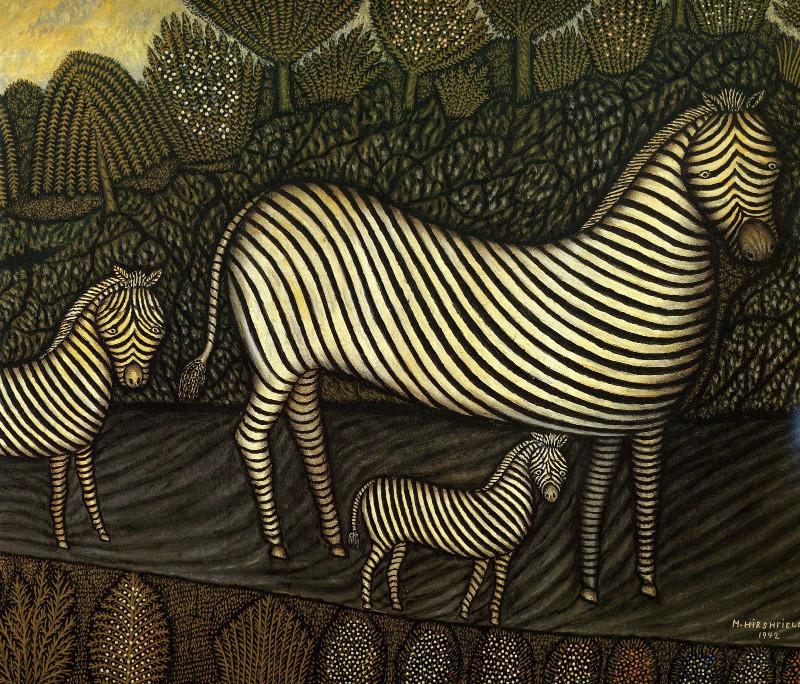

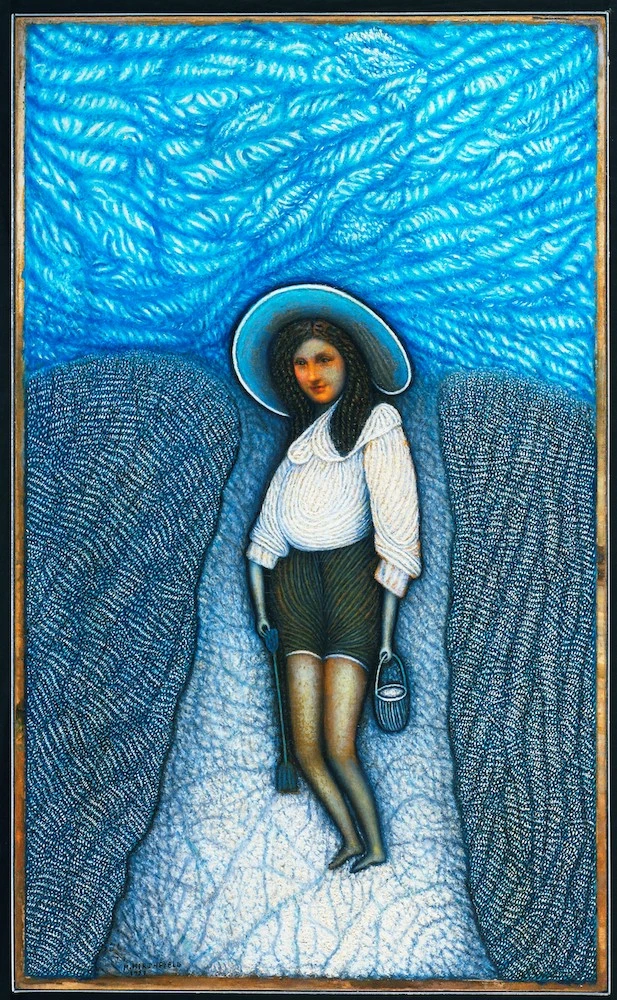

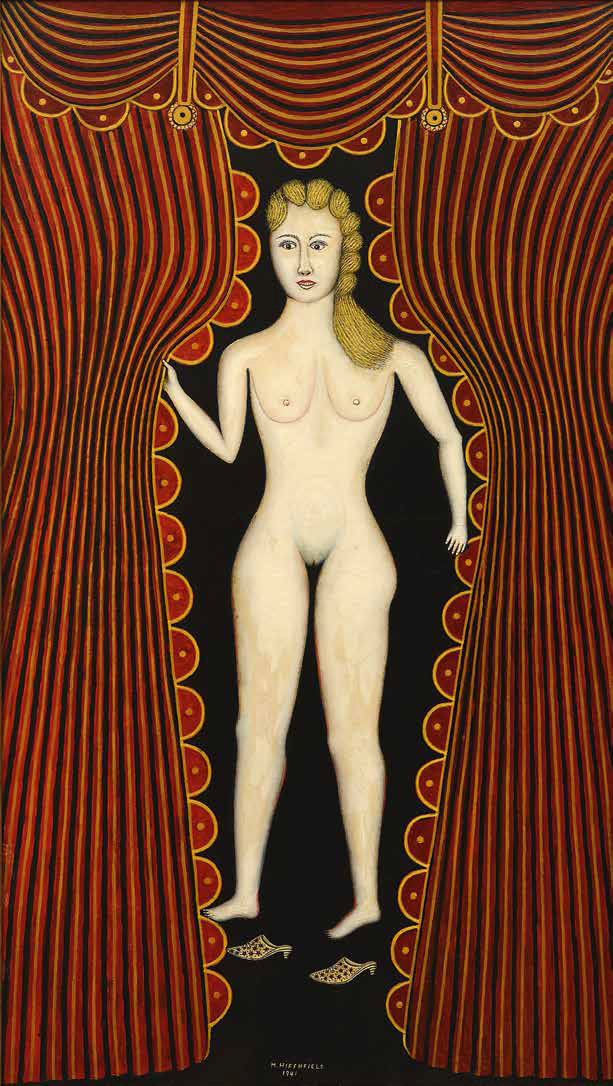

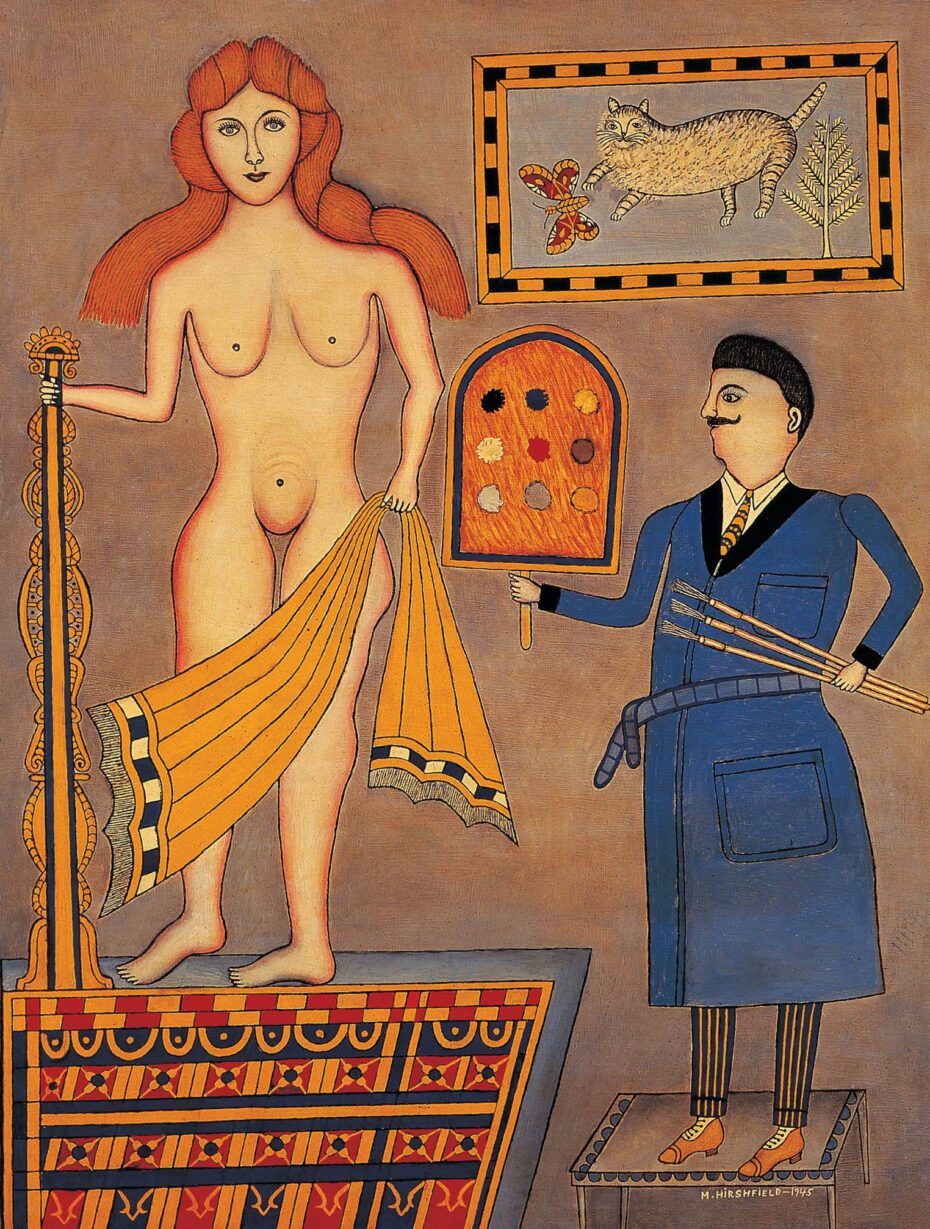

While Hirshfield only painted around 70-something works in his lifetime, he developed a singular and consistent style, focusing on portraying women and animals. He did not rely on models but instead, his memory, and sometimes postcards or other prints.

His inspirations came from everything from Old Testament figures to burlesque posters. His first two paintings were Angora Cat, which featured a white feline lounging on a couch (Janis described it as a “strangely compelling creature… sitting possessively upon a remarkable couch), and Beach Girl, with a bather in white and black attire and an intricately detailed background. In fact, the works took him two years to complete, adding layer upon layer of paint. There was never any blank space in Hirshfield’s work, with luscious textures reminiscent of the fabric materials he had devoted his previous career to.

He soon found a patron in Sidney Janis, a fellow clothing manufacturer and art collector who had a particular interest in self-taught artists. Janis would go on to open an art gallery in 1948 that showcased Abstract Expressionists and famed European artists like Paul Klee, Joan Miró and Piet Mondrian. In 1939, Janis included some of Hirshfield’s paintings in the exhibit “Contemporary Unknown American Painters.” The critics were already harsh, with Newsweek describing Hirshfield as “the least sophisticated of the lot.”

Still, Hirshfield garnered other supporters within the art world, admired by Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, André Breton and most notably Peggy Guggenheim, who purchased the 1941 Nude at the Window, featuring a figure peeking through red curtains. Reportedly paying more for the piece than others by René Magritte and Piet Mondrian, Guggenheim hung it in her New York City home alongside works by Marcel Duchamp, Wassily Kandinsky and Pablo Picasso. Another painting, Girl With Pigeons, (the name is self-explanatory) was included in the 1942 landmark New York exhibit “First Papers of Surrealism,” in which Duchamp created a sort of spider web out of a mile of twine around the artwork. (Kids were invited to play hopscotch and throw balls on opening night.)

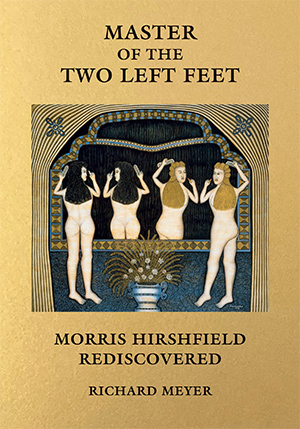

The pinnacle of Hirshfield’s career was a 1943 solo show at the MOMA, featuring the 30 paintings he had so far completed. But he was torn about in the press. Critic Peyton Boswell infamously described him as the “Master of Two Left Feet” in Art Digest. The negative reaction was so strong that it even led to the firing of Alfred H. Barr, the museum’s founding director who had championed Hirshfield’s work, saying in 1942, “Among 20th-century American paintings, I do not know… a more unforgettable animal picture than Hirshfield’s Tiger.”

Morris passed away just 3 years after the MoMA show in 1946 due to a heart attack. Despite a memorial show organised by Janis and Guggenheim, his work was largely forgotten. The art world may have been intent on marginalising his work and other so-called “primitive” artists, but there was likely the element of antisemitism at play too. References to Judaism were a constant throughout his work.

Albeit born a few decades late, curator Richard Meyer is today one of Hirshfield’s most prominent champions. Meyer supposedly reached out to MoMA first about hosting the exhibit, appropriately called “Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered,” but they declined. It didn’t stop Meyer putting together the most comprehensive gathering of Hirshfield’s work ever assembled at NYC’s American Folk Art Museum, featuring 40+ Hirshfield paintings but also 14 recreations of his shoe designs by designer Liz Blahd.

In a 2015 speech that Meyer gave about Hirshfield, he talked about his personal connection to the work, finding a relationship to his Jewish immigrant grandmother, Betty, in paintings centered on women. He was drawn not only to the tactile expertise of textile production but also the female power and visual pleasure that Hirshfield so skilfully conveyed.

“In her skill as a seamstress and her stylishness as a person, Betty provided me an extended introduction to visual beauty, to what I would later come to understand as the beginning of my aesthetic formation,” he said. “But it was Hirshfield that brought me back to Betty and her creative world, not the other way around. Perhaps this is how art functions: as a device that activates or unwillingly recalls earlier moments in our education as viewers and appreciators of form… And so I thank the ‘Master of the Two Left Feet,’ whom I like to imagine resides alongside many other eccentric, luminous spirits somewhere deep in the wilds of Brooklyn.”