“I am to be executed like a criminal at eight in the morning” is a heartbreakingly frank line taken from the final letter written by Mary Queen of Scots, on 8th February 1587, the morning of her execution at the command of her cousin Queen Elizabeth I. This brutally honest letter, addressed to her brother-in-law, Henry III of France from Fotheringhay Castle where she was being held prisoner, was sealed and secured using a complex bygone technique known as letterlocking. The ill-fated queen employed one of the most intricate examples of letterlocking for her final correspondence, the unique spiral lock, indicating that its secrecy was paramount.

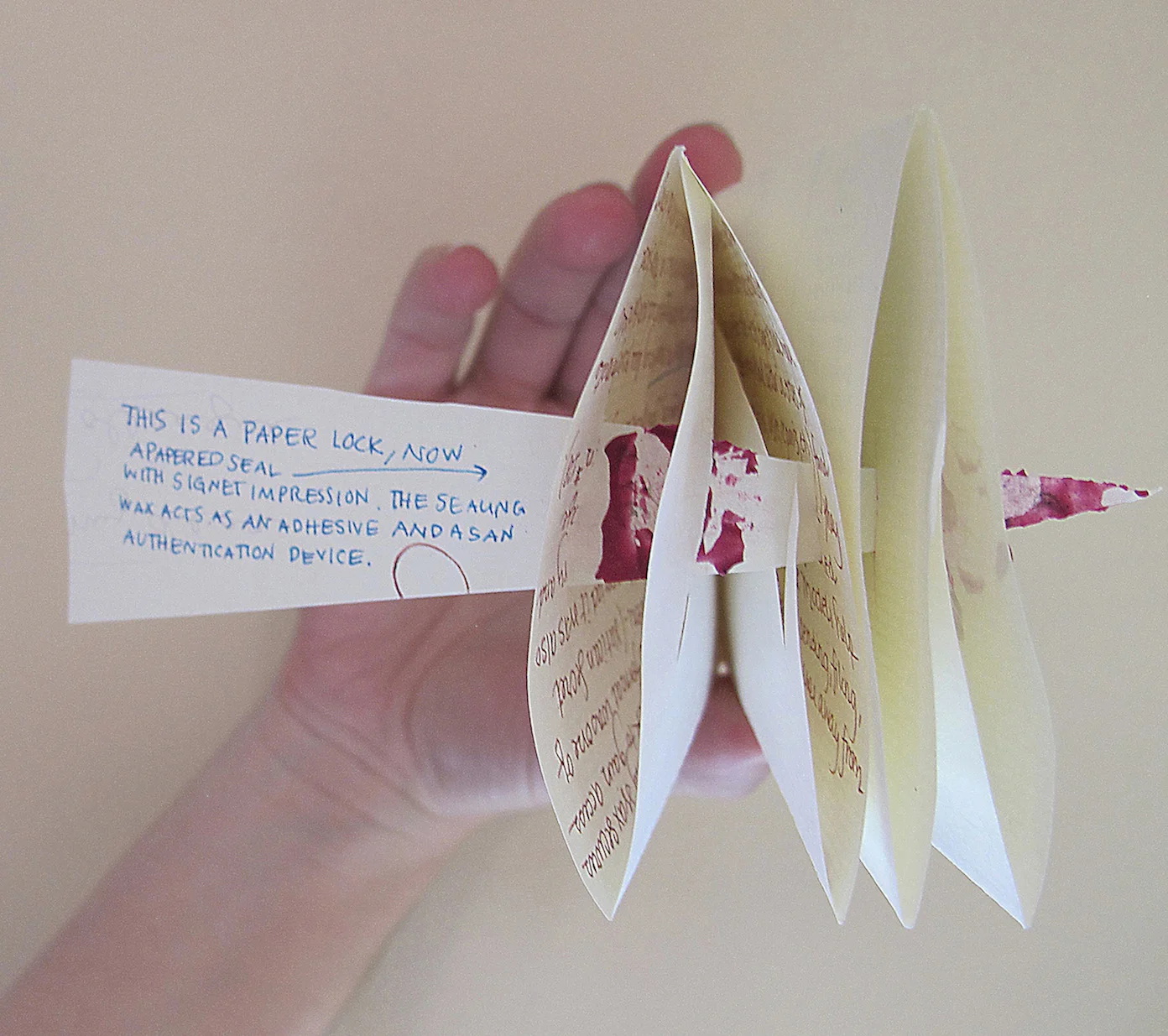

Letterlocking is a method of securing written communication without the requirement of an envelope or packet using a combination of intricate folding techniques. As a precursor to modern envelope-based security methods. It was the traditional method of sealing documents before the envelope became more widely used in the early 1800s and dates back to the thirteenth century when flexible paper first became available. By using small slits, tabs and holes, It involves carefully folding the letter in a specific pattern and inserting locking elements, such as strips of paper or threads, to prevent the letter from being opened without the sender’s knowledge. An extra layer of security was sometimes added with string or a sealing wax. A document became its own envelope which could only be read by breaking the structure, rendering any tampering or interception obvious. The receiver of the letter would need to know the specific unlocking method in order to read the contents of the letter.

In fact, letterlocking became so favoured among the rich and literate that their upbringing or education could be identified by their unique and increasingly complex folding techniques such as the ‘tuck and seal’ or the ‘diamond letter’, as used in the Brienne Collection (more on this later).

By the early seventeenth century, a reputation could be enhanced or belittled by something so seemingly circumspect as how one folded one’s mail, as an unhappy Sir Robert Cecil, Secretary of State for King James VI (and I) makes humiliatingly clear to his teenage son, the unfortunate recipient of his letter:

“I have also sent you a piece of paper folded as gentlemen use to write their letters, whereas yours are like those that come out of a grammar school.”

In an interview with The New York Times, Dr Smith, who lectures on early modern English literature at King’s College London, claimed that the art of letterlocking was so diverse it “became an ambassador for you and had to embody something of you.”

What has become known today as the ‘John Donne lock’ was used by the famous British Metaphysical poet, becoming his trademark design. Donne is the only letter writer known to have used this particularly inventive method; a fact not terribly surprising considering it was not the most secure. If you wish to learn how to replicate the ‘John Donne’, there are tutorials abound on YouTube.

Letterlocking became pretty much obsolete in the 1830s when envelopes were mass produced. After all, who had the time not only to write documents, but to then fold and seal them in ever more elaborate ways, when a ready-made envelope would do the job with one swift dab of a sealing wax?

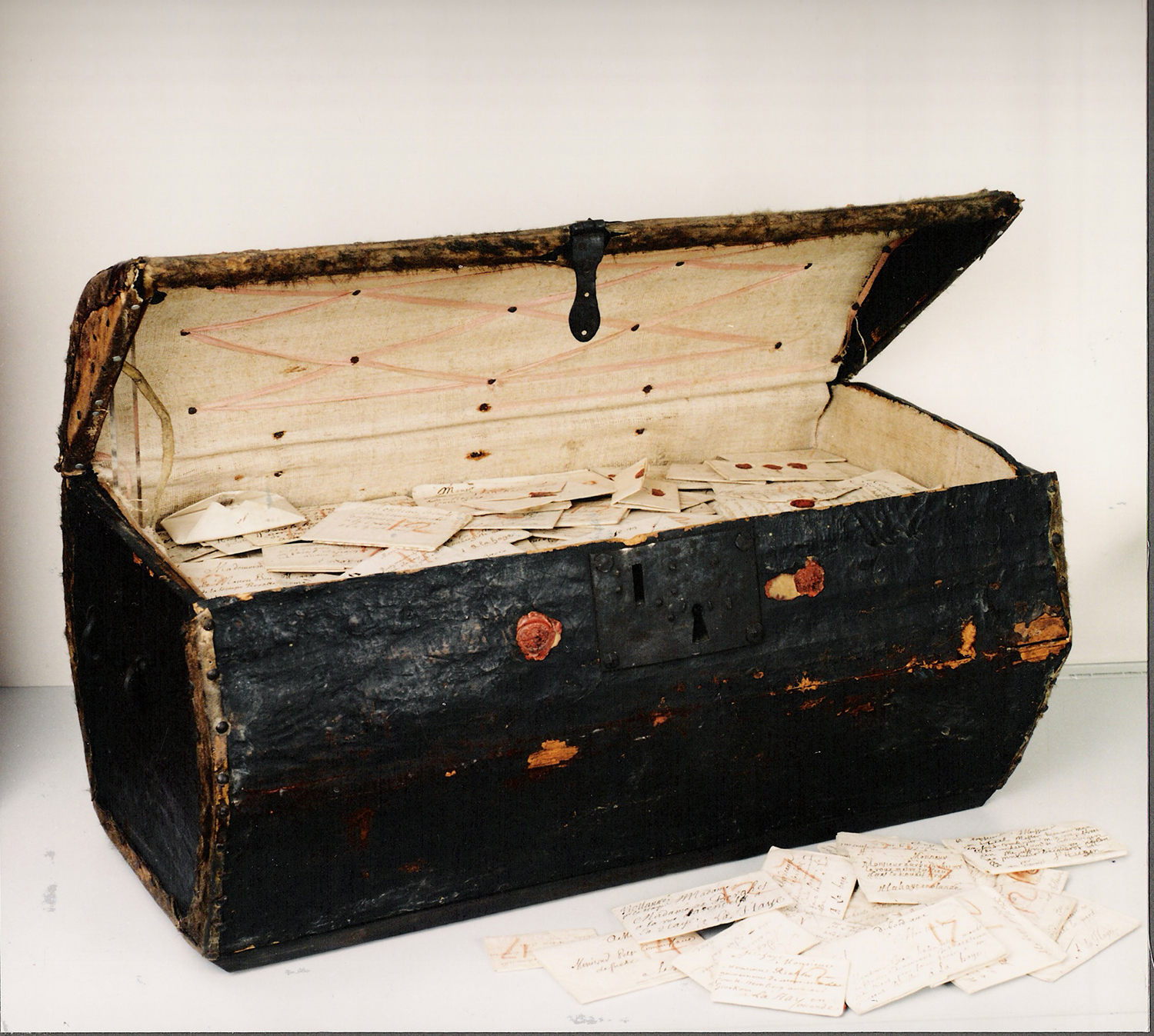

There is little doubt that letterlocking was an extremely effective and rather beautiful method of securing important documents, as the discovery of a postal trunk full of unopened letters, combined with some incredible but obsolete technology, has recently proven. Howard Hotson from the University of Oxford, quoted in the same NYT article confirmed: “It has taken some very sophisticated digital technology to frustrate this sophisticated security system.”

He’s not wrong, it worked for five hundred years.

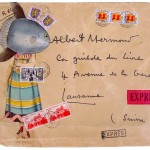

Until, that is, an international project called Signed, Sealed and Undelivered, brought together scientists and humanities scholars to digitally unlock a letter from a postmaster’s trunk full of over two thousand undelivered ‘locked’ letters posted from across Europe to The Hague between 1689 and 1706. In 1926, a seventeenth-century trunk of letters was bequeathed to the Dutch postal museum in The Hague. The letters belonged to postmaster and mistress Simon and Marie de Brienne, hence becoming known as the Brienne Collection.

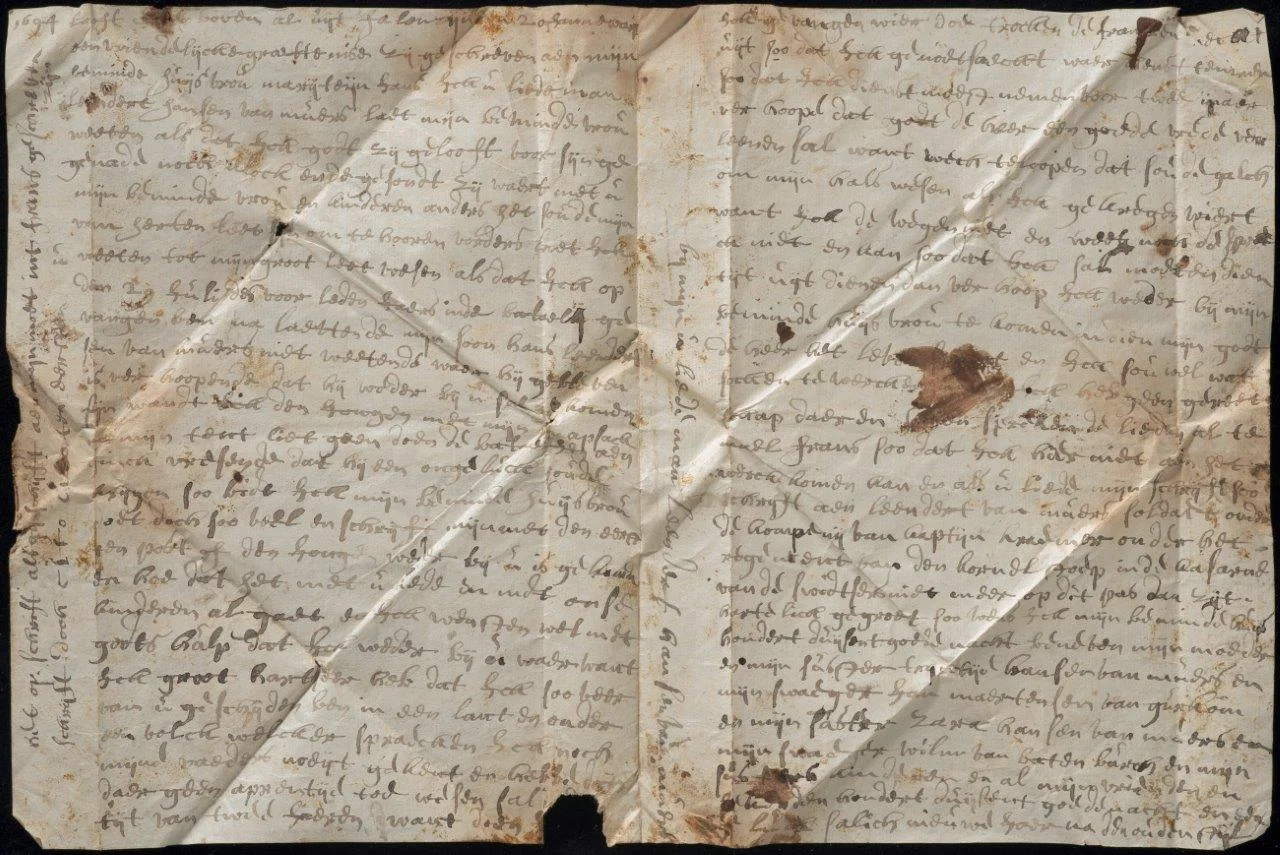

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was the recipient, not the sender who paid for letters, so postal employees often kept uncollected mail as it could be a source of income if eventually claimed. The Briennes clearly hoped for such an outcome but the recipient never appeared and almost 600 of these letters remain sealed and unread. In 2021, however, MIT announced that it had virtually unfolded one letter and were ultimately able to read its contents without needing to break the elaborate lock. In an article published in Nature Communications available online, they explain how it was done. After digitally ‘unfolding’ the letter, it was scanned with an advanced x-ray machine producing a 3D image allowing a computer, as the NYT beautifully describes, to “analyse[ ] the image to undo the folds and, almost magically, turn the layers into a flat sheet, revealing handwritten text that can be read.”

The letter, known as DB-1627, posted on July 31st 1697, was addressed to a French merchant, Pierre Le Pers, presumably based in The Hague, from his cousin Jacques Sennaques in Lille, France. Some of the text was illegible or missing due to wormholes, but the gist reveals a request for a death certificate for a member of the Le Pers family. The wording tells us a lot about the social etiquette (at least in written form) of the time. It ends:

‘

“I also pray that God maintains you in His Sainted graces and covers you with the blessings necessary to your salvation. Nothing more for the time being, except that I pray you to believe that I am completely, sir and cousin, your most humble and very obedient servant”

Jacques Sennaques’ (brienne.org)

The Brienne Collection offers a glimpse of everyday correspondence, and as their website contests, illuminates ‘the fragility of lines of communication at a time when Europe was torn apart by war, economic crisis, and religious differences.’

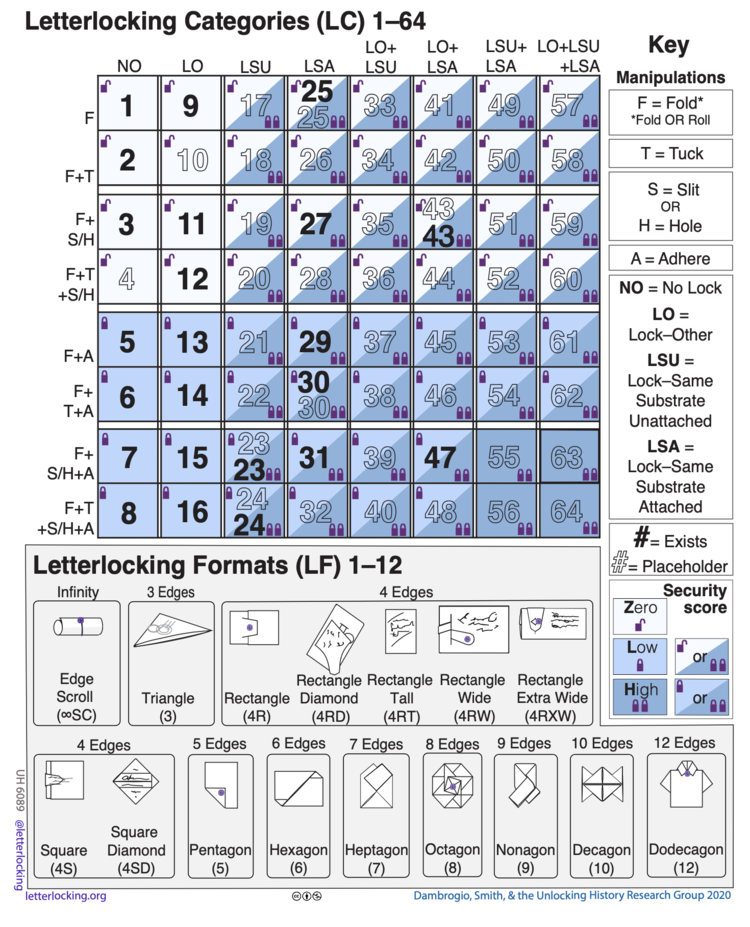

In addition to transcribing the above letter, the Signed, Sealed and Undelivered project also identified twelve formats of letterlocking and sixty-four additional categories such as ‘tucks’, ‘slits’ and ‘folds’, scoring each method for security. Mary Queen of Scots’ spiral lock scored highly.

Letterlocking may be dead, but it is certainly not forgotten. Letterlocking.org dedicates an entire website to the art, complete with a Dictionary of Letterlocking (DoLL), tutorials and a ‘periodic table’ of letterlocking categories. Yes, really!

Let’s return then, to Mary Queen of Scots’ final letter, written and then locked so carefully, with hands about to meet their end. It would seem that secrecy and protection were equally as important five hundred years ago as they are in our digital age today, especially in matters of national importance. In our time of data protection, media exposure and identity theft, it will be interesting to see how many more historical secrets this digital age can unlock.