By 1994 David Bowie’s musical career was in a bit of a quiet phase, let’s say. He hadn’t managed to recreate the massive success of his 1983 album Lets Dance. Ziggy Stardust had long since departed back to the cosmos, The Thin White Duke had been retired, and Bowie’s latest incarnation, Tin Machine, had disbanded. In short, he needed an idea, and if you are David Bowie where do you go for ideas? A psychiatric hospital, of course.

In the small suburb of Maria Gugging, close to Vienna in Austria, behind some trees, there sits a colourful building that in 1994, two rather unlikely characters, David Bowie and music producer Brian Eno came to visit.

At the Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic, which had become known for its “Outsider Artists” in residence during the the post-war era, most of the patients wouldn’t have been particularly concerned with who the visitors were. Uninfluenced, raw, eccentric, mentally ill – these are the labels bestowed upon the “Outsider artist” after all, or should we say, “Insider artist”? A group of people in possession of an unrefined connection to the spring of creativity.

Gugging had experienced a troubled past. After initially being founded in 1898, the Nazis had taken over the running during the war. This was the site of the Nazi Aktion T4 program, where people with disabilities, mental and physical, were experimented on and then murdered for the progression of the so-called Aryan race. It was after the war in the late 1950s that a doctor at the clinic decided to give his patients a diagnostic test inspired by the book Personality Projection in the Drawing of the Human Figure by Karen Machover. The doctor was Leo Navratil and the test was to produce a simple figurative drawing in the hope of projecting a communicative response to try and analyse the personalities of the unreceptive. What he found was that some patients came alive and gave much more than was expected.

Navratil had tapped into a sea of unknown cognitive expressiveness trapped inside by whatever mental affliction tormented the patients. This would begin the facility’s eventual transformation from Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic to the Art Brut Centre Gugging. Jean Dubuffet, the French painter had christened an unrefined unorthodox approach to art “Art Brut“, a link to his days as a wine merchant – brut in French meaning raw or unsweetened. Visual Art was now used as a therapy at the centre, and in 1962 when Navratil published his book Schizophrenia and Art, Gugging started to attract attention. Artists such as Arnulf Rainer, André Heller, and Peter Pongratz, would become involved and champion the centre. They seemed as much captivated by what was being produced as by the mystery of where the inspiration was coming from. Navratil had begun to choose patients to inhabit the space which had morphed into an art studio, a Psychiatric Clinic and an art gallery.

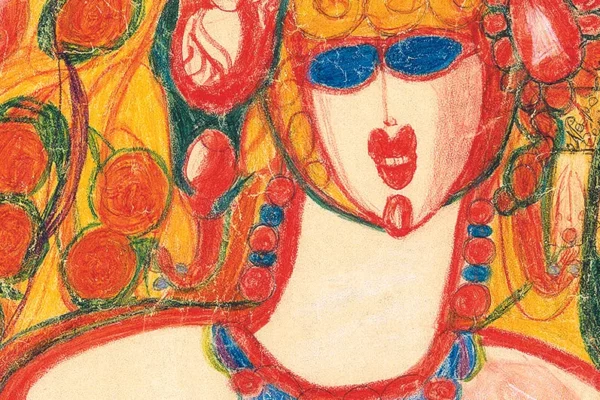

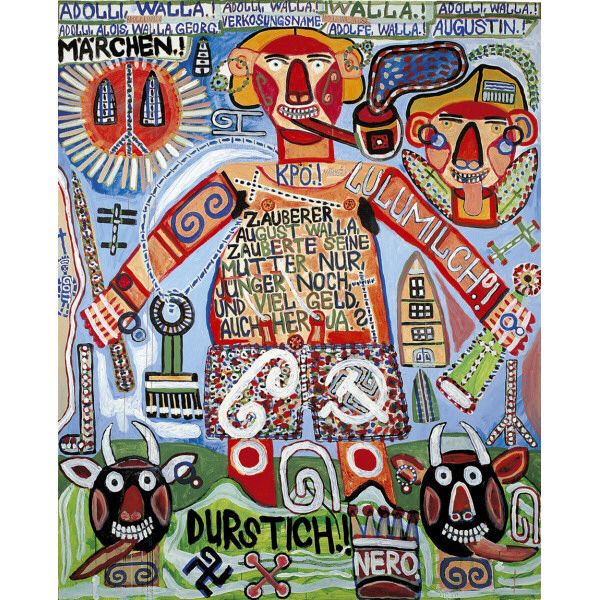

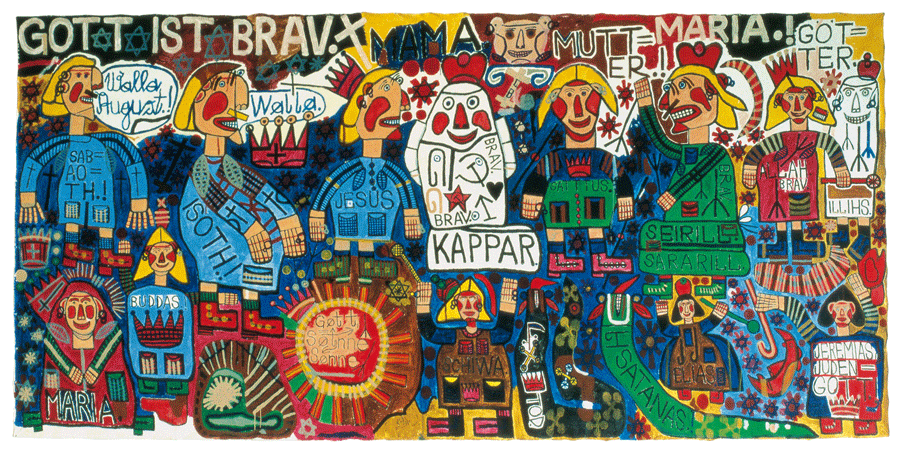

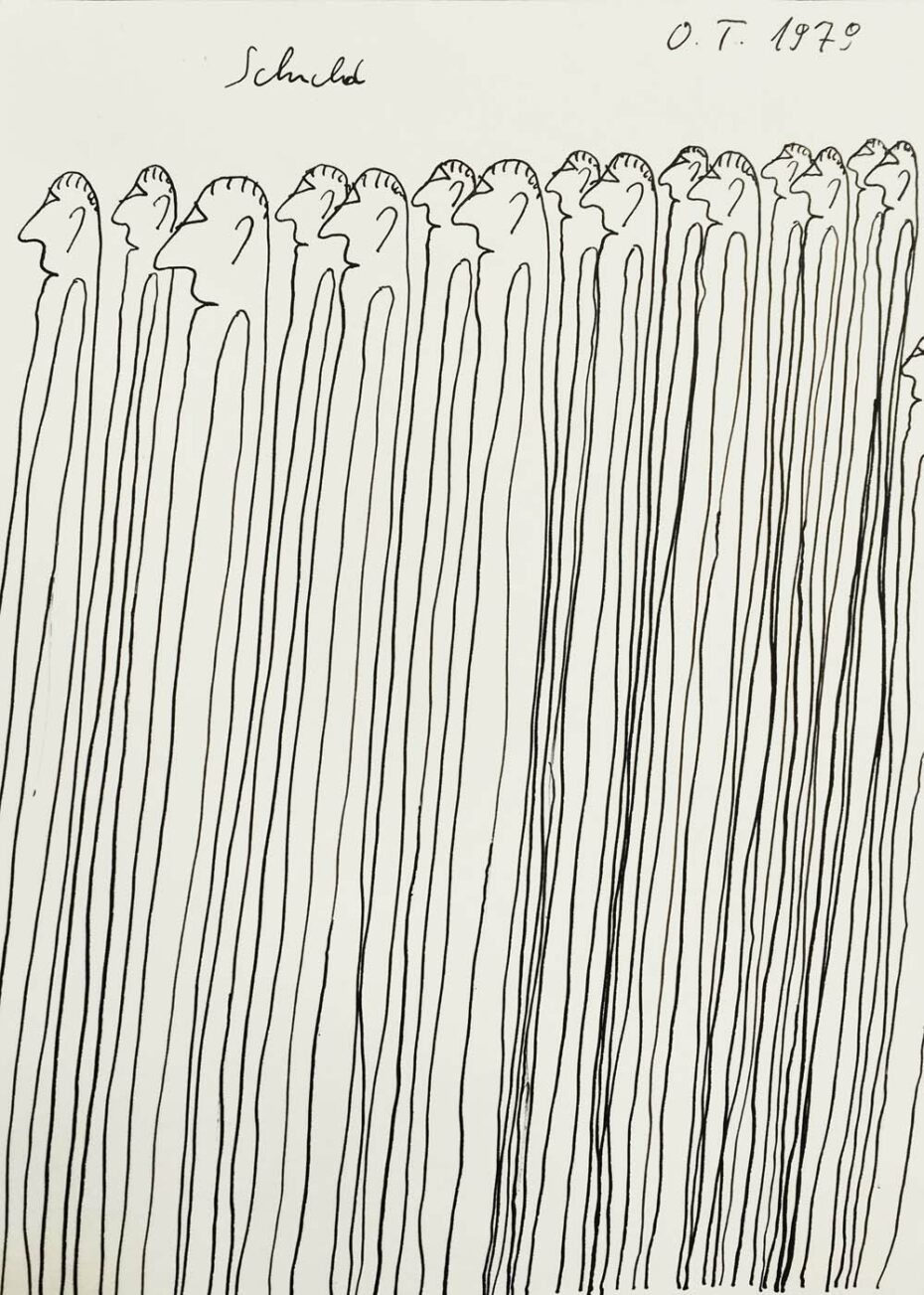

In 1970, they had their first exhibition, which included works by August Walla an Austrian-born artist whose world of self-made symbolic mythology and his own language fed his vibrant oeuvre. Walla suffered from schizophrenia and had thought Hitler was his father. After he had threatened to set himself on fire he had been placed in Gugging.

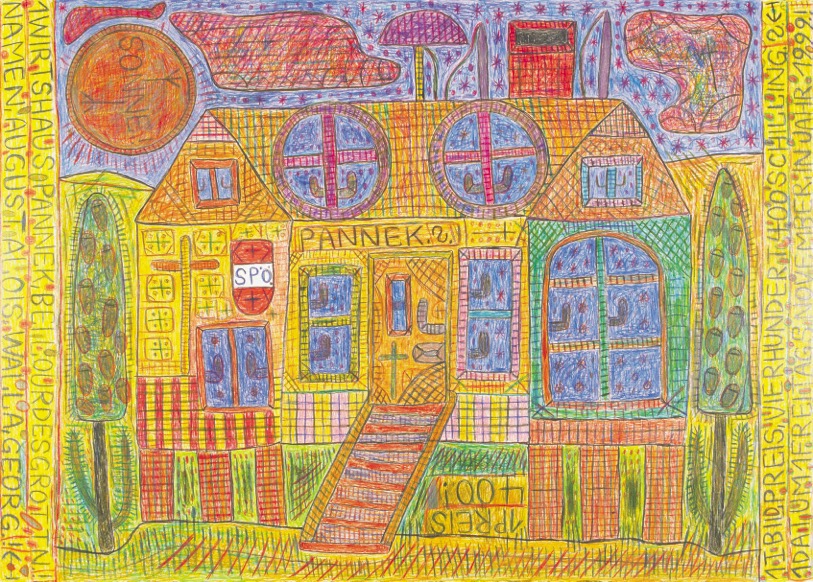

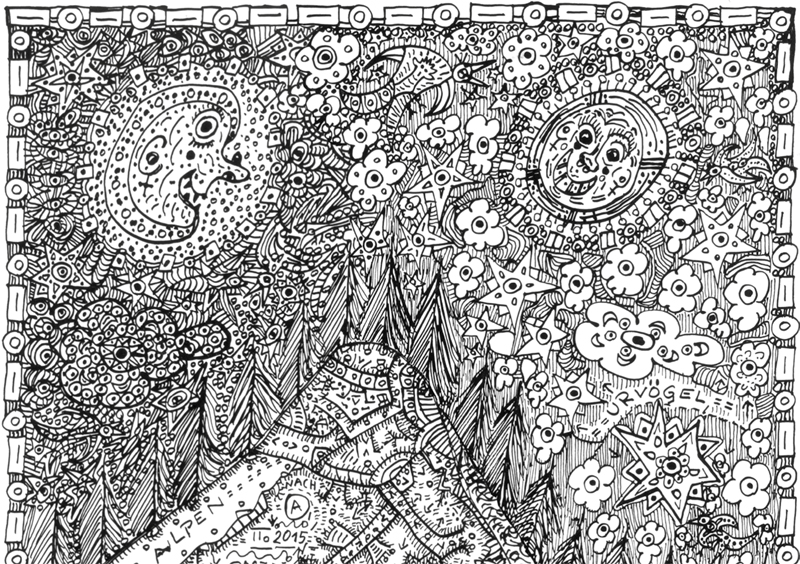

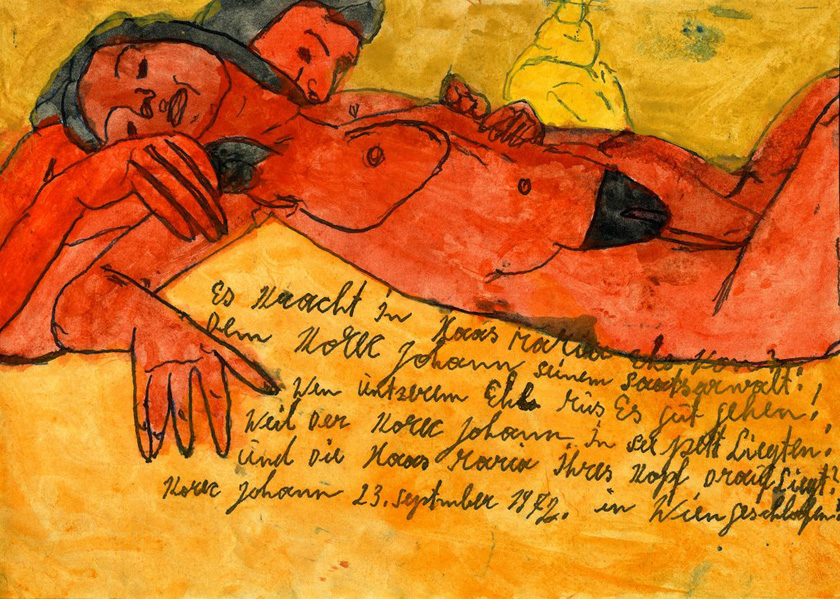

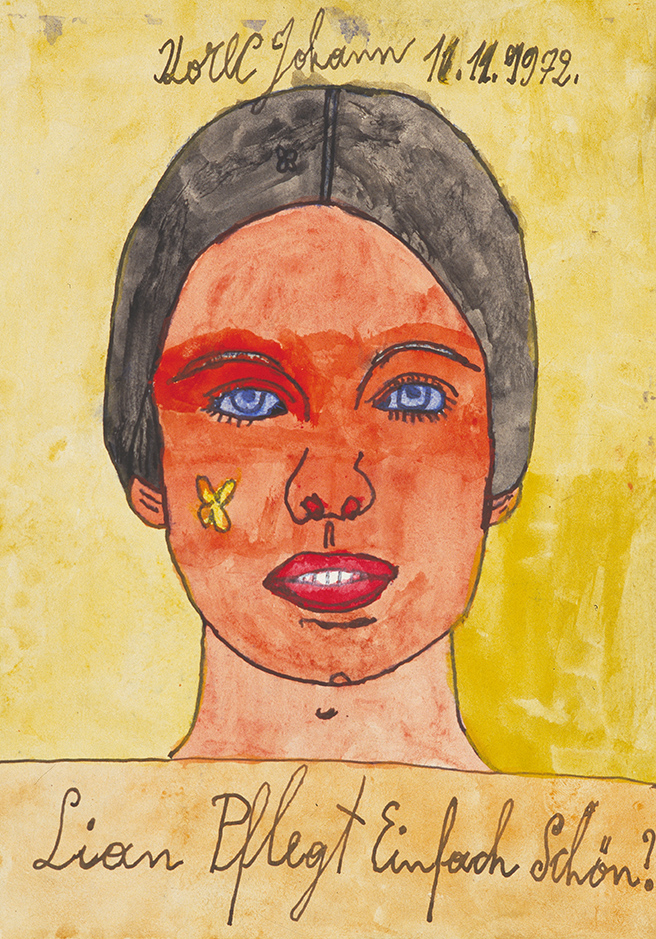

Johann Garber has lived at the clinic permanently since 1968. His art explores an intricate world with dense texture and flowing Elysian wanderings. Johann Korec narrates his personalised landscape where eroticism and the written word envelop with ink and colour. Korec grew up attending specialized schools before working as a shepard at a young age until he was committed to Gugging in 1958.

By the time Bowie decided to take a trip to Gugging, Dr Johann Feilacher had taken over the centre and had renamed it The House of Artists. Bowie had recently teamed up again with the electronic glam druid producer extraordinaire, Brian Eno.

The two had previously collaborated on Bowie’s Berlin trilogy of albums Low, Heroes (1977) and Lodger (1979). A new approach was needed and whenever Bowie seemed to be stagnating he would look for a catalyst of reinvention. In the 1970s, he had employed The Dadaists ‘cut up’ or découpé, a literary technique used by William Burroughs to assist the writing process. So when Bowie’s friend the artist André Heller invited him and Brian Eno to Gugging, they eagerly accepted.

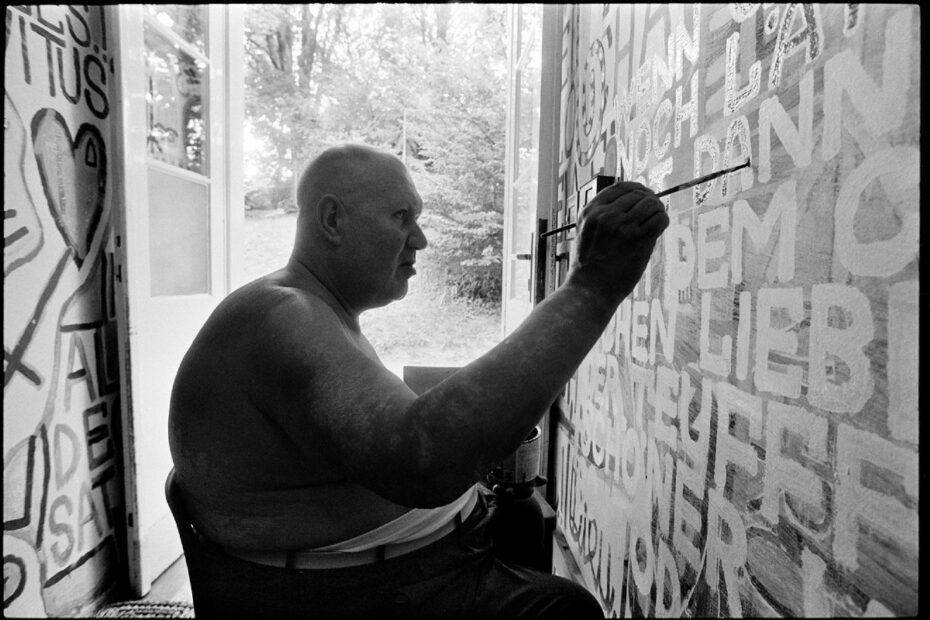

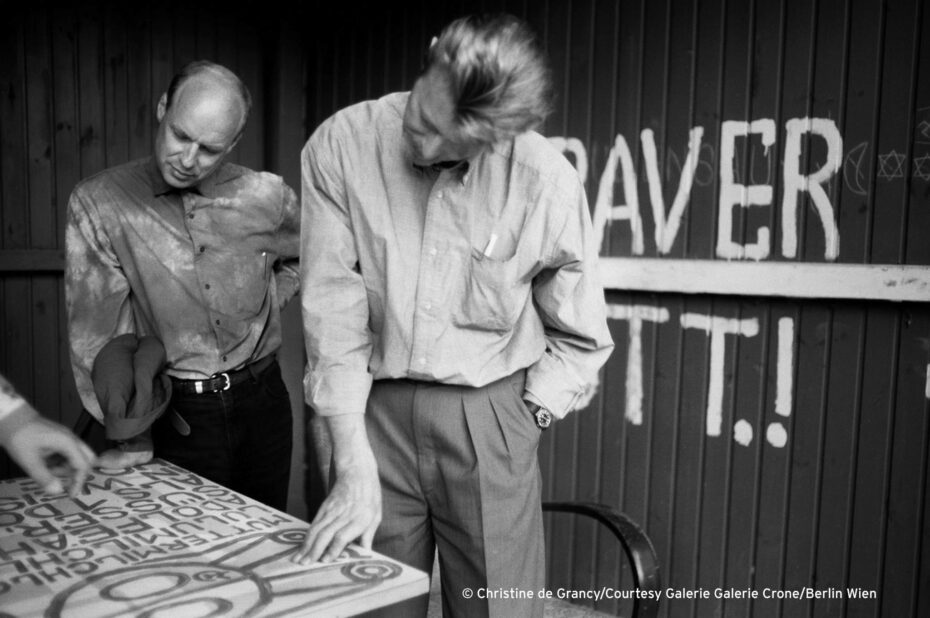

They arrived in September 1994 with the photographer Christine de Grancy to capture the experience. The residents had adorned the outside of Gugging by this point with murals, a vibrant invitation into their world. Bowie and Eno moved through the house of artists interacting with the residents. For him, this held something more personal than just an impetus to the creative process. There had been mental health issues in his family; his mother Peggy and his half brother Terry had suffered from some degree of schizophrenia. Terry had been 10 years older and had a major influence on Bowie’s young life, introducing him to jazz and literature. In 1985, Terry escaped from the Cane Hill Mental Institution and tragically took his own life, Bowie would later recall in an interview.

“[It was] the greatest serviceable education that I could have had. He just introduced me to the outside things,” he added, “I saw the magic, and I caught the enthusiasm for it because of his enthusiasm for it. And I kinda wanted to be like him.”

Mental illness and psychosis would be a recurring theme through out Bowie’s career, from Aladdin Sane to All the Madmen. The shackles of a hereditary mental illness always lurking in the shadows.

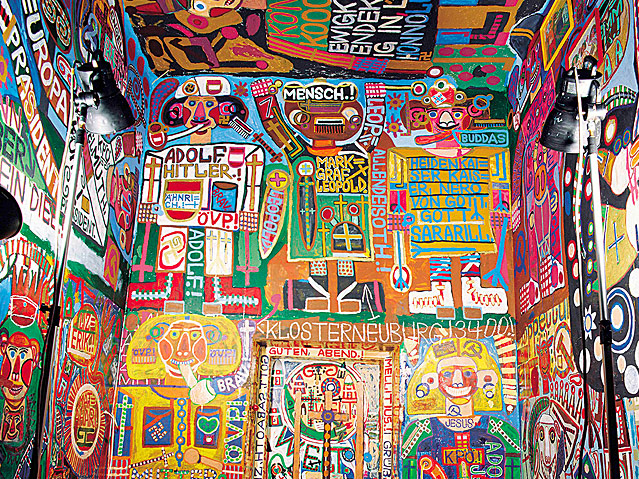

Inside, the residents’ creations had spilled out from the paper and canvasses and now covered walls and objects. As if their creative imagining could not be contained anymore; an obsessive monologue that leads forever onward. Everything they can’t articulate in the constraints of their illness can find an outlet in their art. The work is individualistic, each with a theme and a secret language that is known only to them. There is a naivety that can’t be replicated and a pure unconscious expressiveness that captures the imagination. For three hours, Bowie and Eno immersed themselves inside the world of the “Outsider” artists.

They chatted, made sketches and notes, met the residents, had lunch, then left. If Bowie was looking for insight, what did he glean from his time there, the hidden secret to artistic enlightenment or a more personal connection to understand something that had touched his life? Either way, Bowie and Eno went away and made the album 1.Outside. It was initially meant to be one of three, but remains a stand-alone piece.

The album sold moderately well and has been labelled as Bowie’s most challenging record. It was described by critics as “bold and fascinating”, as well as “baffling and overreaching”. Whatever Bowie was looking for at Gugging may have evaded him or maybe he just kept it inside, for himself.

Photographs of Bowie’s visit by photographer Christine de Grancy.