Theirs is a fairy tale with all the elements that titillate and intrigue us mere mortals no end: a glamorous royal couple living in the lap of luxury, a marriage at an unimaginably young age, the flamboyant holidays on the Côte d’Azur in the company of Man Ray, a jaw-droppingly avant-garde palace, her tragic, untimely and mysterious death – it has all the hallmarks of a 21st century sizzling hot paparazzi-frenzied tabloid obsession. Only, the Maharaja and Maharani of Indore (the ‘king’ and ‘queen’ of one of the many princely states of British India) were young royal socialites in the first part of the 20th century, and are perhaps one of the most overlooked society couples of the modern age.

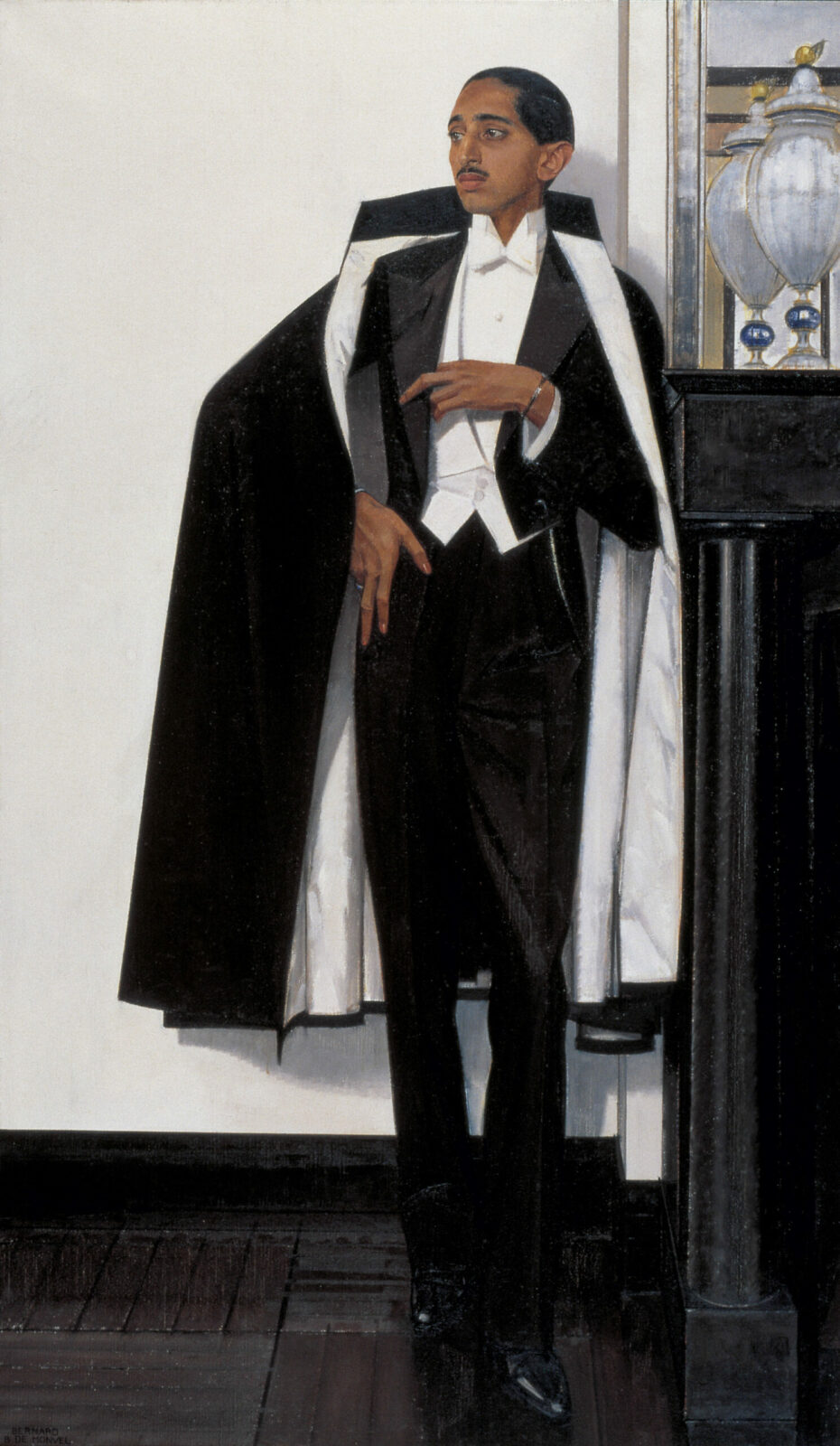

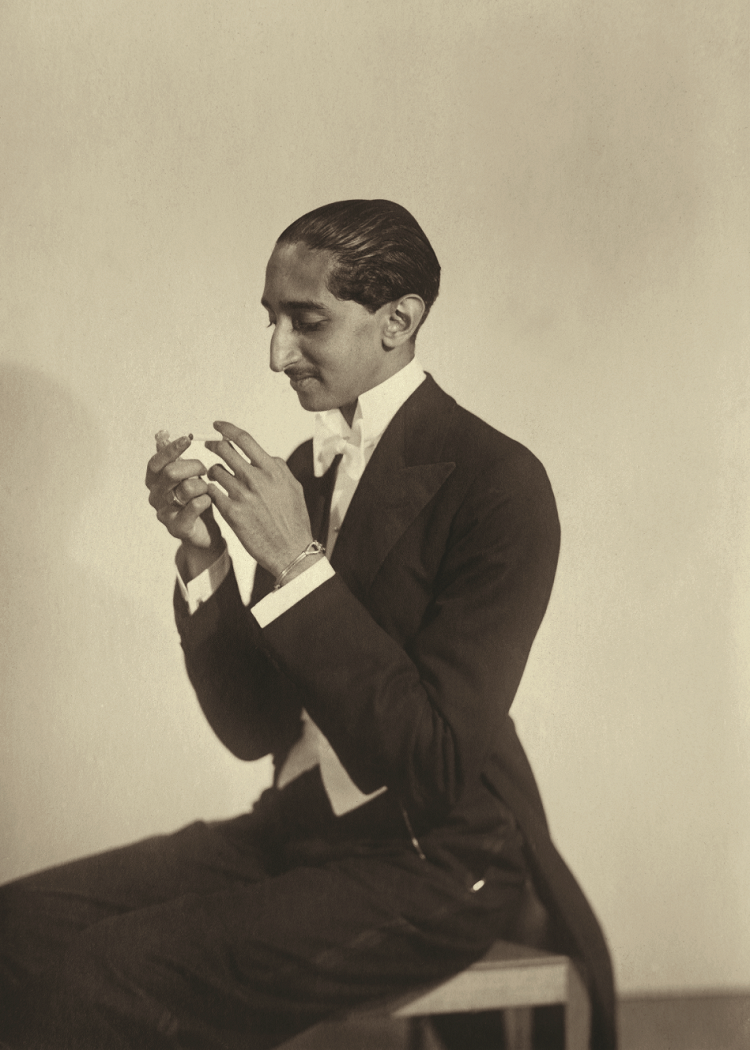

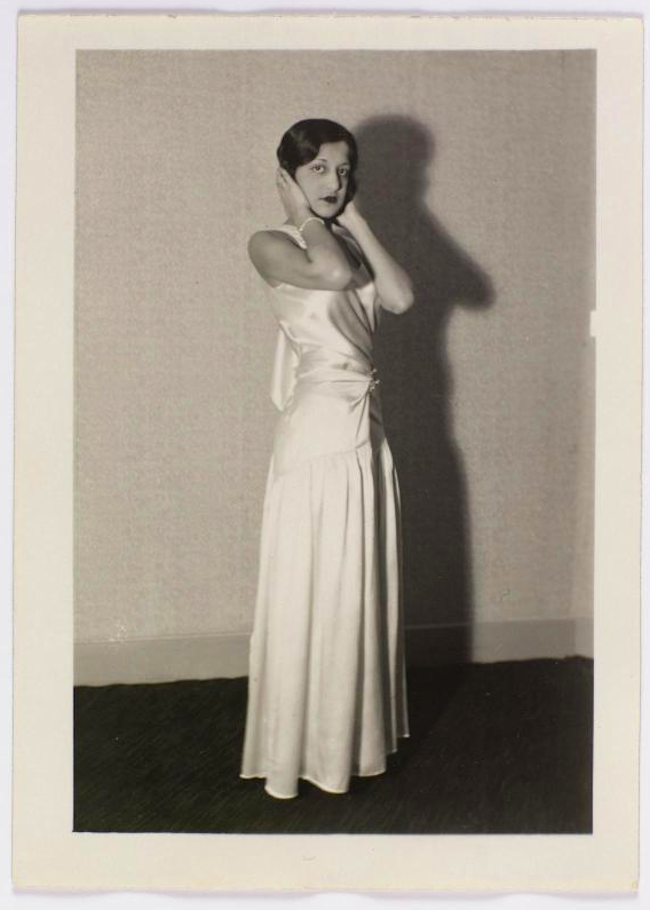

Their contemporary taste for design, from houses to furniture and jewellery (the Maharaja was a legendary figure in the design world) and their extensive and obsessive cosmopolitan travel sojourns (they hardly spent any time in India) speak of a couple who were not only gorgeous, gifted and adventurous, but also well ahead of their time, not merely seeking the endless thrills but also going out of their way to create them. As a couple they looked enviably elegant; individually they were equally awe-inspiringly striking: he cutting a distinguished-looking figure – tall and lean, sporting a fashionably razor-thin moustache and dressed in the best-cut designer suits, she the picture of tasteful glamour in her 1920s silhouettes, complete with twenties eyebrows, flapper hairstyle, sumptuous furs and the world’s most perfect diamonds. Photographers like Man Ray doggedly followed them around to immortalize some of the glam and the glitz on his legendary lens. Dreamy portraits were painted of them by the likes of Bernard Boutet de Monvel. And yet – not many people have heard of these modernist Maharajas.

Perhaps a suitable place to zoom in on this epic love story is at the point where Yaswant Rao Holkar II married his bride Sanyogitabai Holkar of Indore in 1924. She was merely eleven years old at the time, he sixteen. He became Maharaja two years later and was invested with full powers in 1930, succeeding his father Tukojirao Holkar II who abdicated in his favour in 1926. Both Yaswant Rao Holkar II and Sanyogitabai Holkar were products of a British education. He was schooled at the prestigious Charterhouse in Surrey, then followed Christ Church Oxford. She too was privately educated in England.

The young couple craved adventure of a cosmopolitan kind: they travelled so extensively to Europe and America that they were criticized back in India for hardly ever spending time on home soil. They evidently adored the allure of foreign travel that comes with aristocratic privileges, and loved every opportunity to rub shoulders with the bold and the beautiful – film stars, royalty, designers, creatives and famous artists – wherever they went, they were lavishly entertained and thrived on being part of Europe and America’s young super elite club.

They had unfettered access to Hollywood stars like Gary Cooper, Cecile B DeMille and Gail Patrick, who welcomed them backstage and called them friends. For a few years during the Jazz Age, the world was their oyster, a playground, from Cannes to Hollywood, they feverishly explored and drew much creative inspiration from.

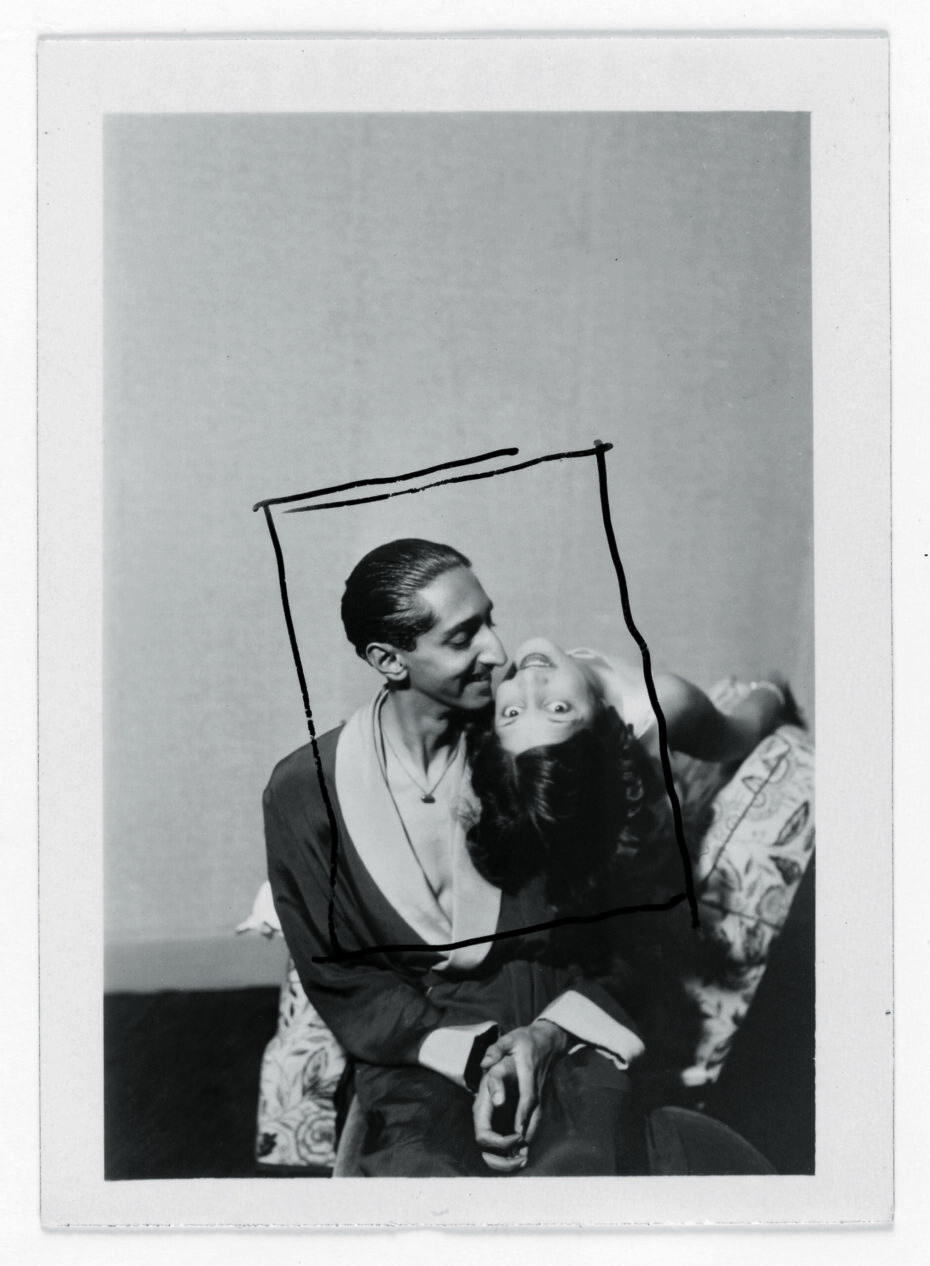

Man Ray mused over the striking couple;

“The Maharaja of Indore came to the studio [in Paris] to be photographed, also in Western clothes – sack suits and formal evening dress. He was young, tall and very elegant. I got a substantial order from this sitting. […] Next year, the Maharaja was in the South of France with his young bride. He had taken an entire floor of a hotel in Cannes for himself and his retinue. I arrived in Cannes before noon, was assigned to my room in the suite […] The Maharanee was an exquisite girl in her teens. She wore French clothes, and a huge emerald ring. The Maharaja had bought it for her that morning while taking a walk. […] The next day I was asked to bring my camera to their suite […] to make a series of photographs that would be a record of their honeymoon. First, I had to play some jazz to which the subjects danced, and then they sat down holding hands. I made a few exposures, after which I suggested that they pose separately for individual portraits.”

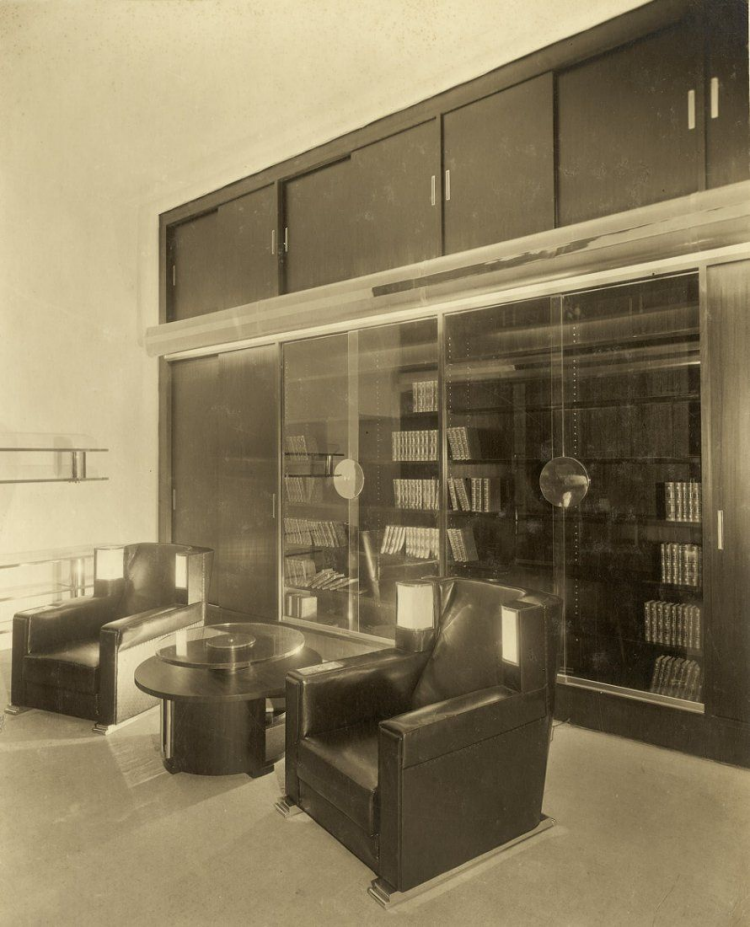

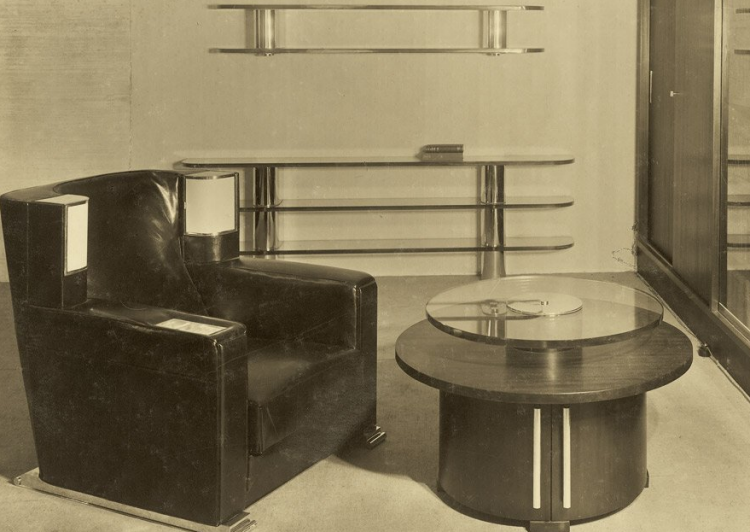

Fuelled and fed by all things aesthetic and sparing no expense to pursue their passion for things innovative, the couple commissioned the design and build of a shockingly modern palace for themselves in Indore, called Manik Bagh (“Ruby” or “Gem Garden”) between 1930 and 1939. The head architect was a friend, Eckart Muthesius. The second-to-none Art Deco palace was built in the new International Style, with its Charles Rennie Mackintosh-like sheer walls and gables of gleaming white modernism. (Eckart Muthesius’ father, Hermann had championed Mackintosh’s design for the international ‘House for an Art Lover’ competition in 1902 as a ‘new style of art’).

All the expertise required for this avant-garde masterpiece was a product of Europe – the building was designed and created on the continent and the scores of select interior designers, architects and other creative masterminds to the project famously included those on the creative ‘it’ list of the day. Swiss-French architect and designer Le Corbusier, Art Deco furniture designer Ruhlmann, Art Deco silversmith Puiforcat, furniture designer Eileen Gray and modernist Romanian sculptor Brancusi. This project was a celebration of the new-age materials of the day: metal, synthetic leather and glass. Each room had a colour focus too. The U-shaped Bauhaus/ Art Deco palace with its forty rooms, marbled floor and designer furniture was completed in 1939. On the way, no expense was spared to create this heirloom fortress; furniture was dismantled in Berlin and shipped to Indore. Baccarat silverware galore, beds by Louis Sognot and the black and orange geometric abstract painting-like carpets were designed by Ivan da Silva-Bruhns. It exuded luxury, elegance, comfort and innovation. In hindsight, all perhaps rather contradictory to the underlying socialist ideals of the modernist designers.

The Maharajas had an insatiable appetite for goodies: the architect of the palace was also commissioned over the years to create designs for a furnished private train, an aeroplane, a caravan, a riverboat and summer palace. The latter two projects never materialised. The Maharaja had a keen eye for jewellery too, and the top jewellery establishments of the time – Chaumet, Harry Winston, Van Cleef & Arpels etc – were instructed to create the most exquisite pieces for Sanyogitabai Holkar. She was famously photographed and painted sporting the most exotic pearl-shaped diamonds created by the diamond companies vying for her attention.

During the years the palace was built, the couple had a daughter, Usha, born in Paris in 1933. Tragically the beautiful Sanyogitabai Holkar of Indore had a very short life and she died at 22. Information surrounding her death is oddly vague. Allegedly she was in Switzerland (where, incidentally she was also born) for a ‘cure’, but things unexpectedly turned for the worse.

She left behind her 4-year-old daughter Usha and her young husband. The Maharaja married twice again in his lifetime, both wives were American divorcées. With his third wife, he had a son, but his title was passed on to his firstborn daughter. After Indian independence, the Maharaja served as a high ranking official until 1956, thereafter, he was employed by the United Nations and died in Mumbai at the age of fifty-three.

The splendid Art Deco palace at Manik Bagh was completed, but with the untimely death of the Maharani, the intended accompanying grand water gardens were never finished. The outbreak of the Second World War saw the European designers leave India and the Maharaja retreated into his own private world, returning less and less to the palace. Post war, India was a new independent state, no longer under colonial nor any Maharaja control.

The crisp modernist exterior of the palace was lost, veiled behind a bedraggled clutter of painted gables, tin roofs and awnings. In 1980, the interior fittings were auctioned off at Sotheby’s and today the building is used by the Office of the Commissioner of Customs & Central Excise.