The antics of those with blue blood don’t shock us, in fact we covet their blatant flaunting of taboos and we (albeit secretly and with much envy) gag at what seems like their infinite potential and unlimited opportunities for fornication, frolicking and cavorting. Having said that, within the ranks of nobility there are those who are heads and shoulders above the rest when it comes to outlandish behaviour – and quirkiness of ancestry for that matter. The wildly unorthodox life experiences of Baroness Vita Sackville-West, prolific lesbian and bisexual lover, mother of two, diplomat’s wife, bestselling novelist of over 35 books, poet, newspaper columnist, letter writer, diarist and passionate garden designer, are the ultimate case in point. She yo-yoed with passionate fervour between a bevy of fabulous women and her steadfast bisexual husband. You may think Vita’s key legacy is her decade-long romantic and literary canoodling with Virginia Woolf and the spicy love triangle between Virginia, Vita and her childhood obsession Violet Keppel, but that’s just one facet. There was infinitely more to this passionate bohemian with her insatiable lust for life, for literature, for women, for men as well as for the natural world. It seems unsurprising then, that in the very end, her plants and garden effectively excited her as much as her writing or her romps within a ménage à trois. Let us now meet literature’s real-life Orlando…

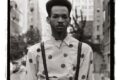

Vita was the grand-daughter of a notorious Andalusian dancer, Pepita (Vita would forever be thanking her for her hot-blooded, free-spirited ‘Romany’ genes) and daughter of an illegitimate child, Victoria, who got marriage proposals from the likes of Rudyard Kipling, Auguste Rodin, Henry Ford and the widowed President of the US Chester Alan Arthur, but ditched them all for her own cousin, Vita’s father, Lionel. While Vita’s mother continued entertaining herself with a host of famous lovers like financier J.P. Morgan and Sir John Murray Scott, Lionel would in turn, swap Victoria for an opera singer. It’s clear Vita Sackville-West arrived into this world on March, 9th, 1892 to a set of rather eccentric ancestors and it’s at Knole House in Kent (built in 1455) with its 1000 acres and fifty-two staircases that she grew up.

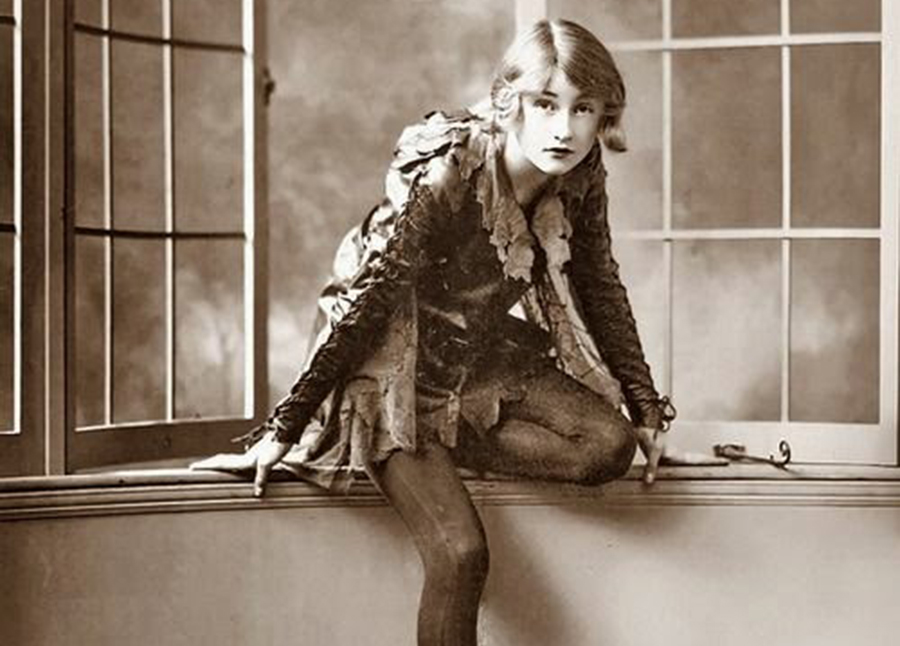

Teenage Vita was shy, lonely, awkward and felt intellectually inferior. She moved to an elite London girls’ school after a stint of home-schooling and recalls often getting into trouble for “wrestling with the hall-boy” and being particularly fond of her pocket knife. Vita wrote incessantly (apparently she was inspired by Cyrano de Bergerac at age twelve) and by age eighteen, she’d finished eight full-length novels, some ballads and and a few plays. An early love interest was Rosamund Grosvenor, a fellow student two years her senior with whom begin exploring her sexuality – chaperones were evidently unsuspecting.

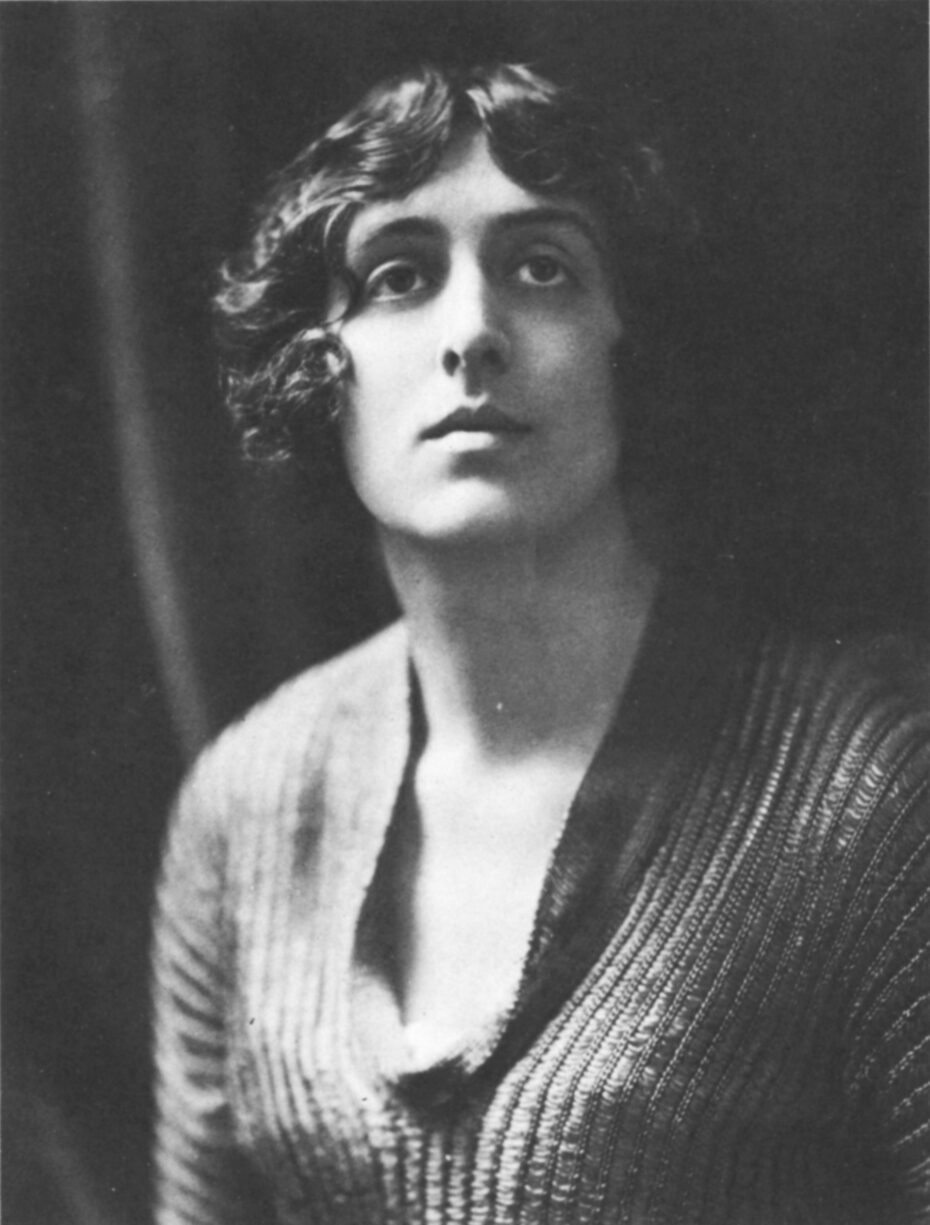

She started a second sexual relationship in her early teens with another girl from school, Violet Keppel, described by Vita as “this extraordinary, this almost unearthly creature”. This relationship of immeasurable passion, jealousy and psychological dependence would continue for many turbulent years.

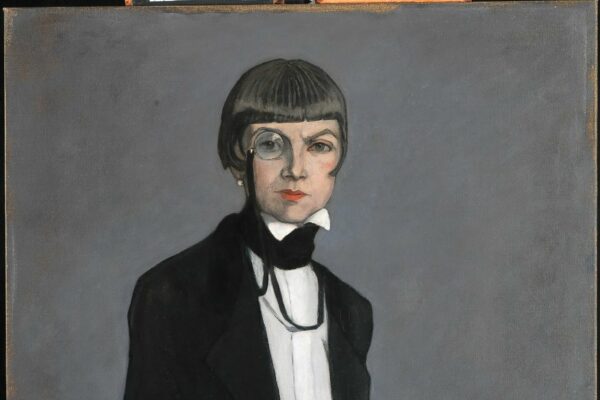

Vita the debutante, just like her mother, received plenty of male interest and didn’t shy away from relationships with men. Florentine nobleman Orazio Pucci, the Duke of Rutland and the Earl of Harewood all staked their claims. To the surprise of her disapproving parents, in 1913, Vita accepted a proposal to marry a penniless diplomat at the British embassy in which “not as much as a kiss was exchanged”. You might even say Vita intentionally chose a suitor that wouldn’t interfere too much with the pursuit of her more private pleasures. Both Violet and Rosamund were present at the union (poor heartbroken Rosamund was a bridesmaid) and indeed, Harold and Vita’s marriage turned out to be a very ‘open’ one, that allowed both parties to enjoy same-sex relationships, although she did become pregnant with their child just a year later. They settled in Kent and went on to have two sons, but all the while, Vita and Violet Keppel kept exchanging passionate letters. Violet, pressured by her family, ultimately married a military man, Denys Trefusis, much to Vita’s despair. Still, over the next years, the women frequently escaped together to France, Vita, often dressing as a man and posing as Keppel’s husband. She wrote in 1918 about the liberation of her masculine side, “I went into wild spirits; I ran, I shouted, I jumped, I climbed, I vaulted over gates, I felt like a schoolboy let out on a holiday… that wild irresponsible day“. Both women’s mothers tried to force them back to their husbands, but Vita and Violet made a pact not have sex with their spouses.

When gossip about the women’s loose behaviour reached London, their husbands were ordered by red-faced in-laws to chase them down and bring their wives back into the folds of polite society. Harold and Denys set out to find the women in a two-seater aeroplane and tracked them down in Amiens where a very public and heated exchange ensued. Harold told Vita that Violet had been unfaithful to her – with her own husband Denys! Fuelled by jealousy and the impossible pressures of an unaccepting world, the lovers went their separate ways, before briefly reuniting romantically one last time in 1921 in France. “I treated her savagely, I made love to her, I had her, I didn’t care, I only wanted to hurt Denys”, Vita wrote (Paris Review).

By 1923, Vita was in her mid twenties in the midst of the roaring twenties, and not quite finished exploring her desires. She had a whirlwind affair with a married poet Geoffrey Scott, who lived in the Villa Medici in Florence, ultimately resulting in the collapse of his marriage. Her husband Harold, meanwhile, was posted to Tehran and she wrote A Passenger to Tehran about her experience visiting him there. The Land (1926), an epic and prize-winning poem was also in the making; at the same time she tried her hand at landscape designing, inspired by Scott’s olive grove at the Villa Medici.

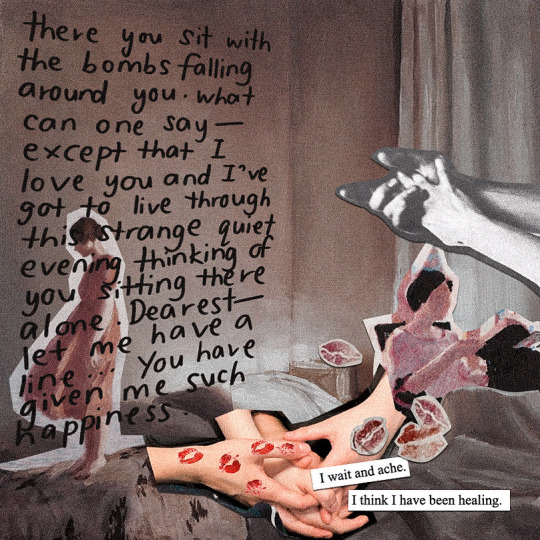

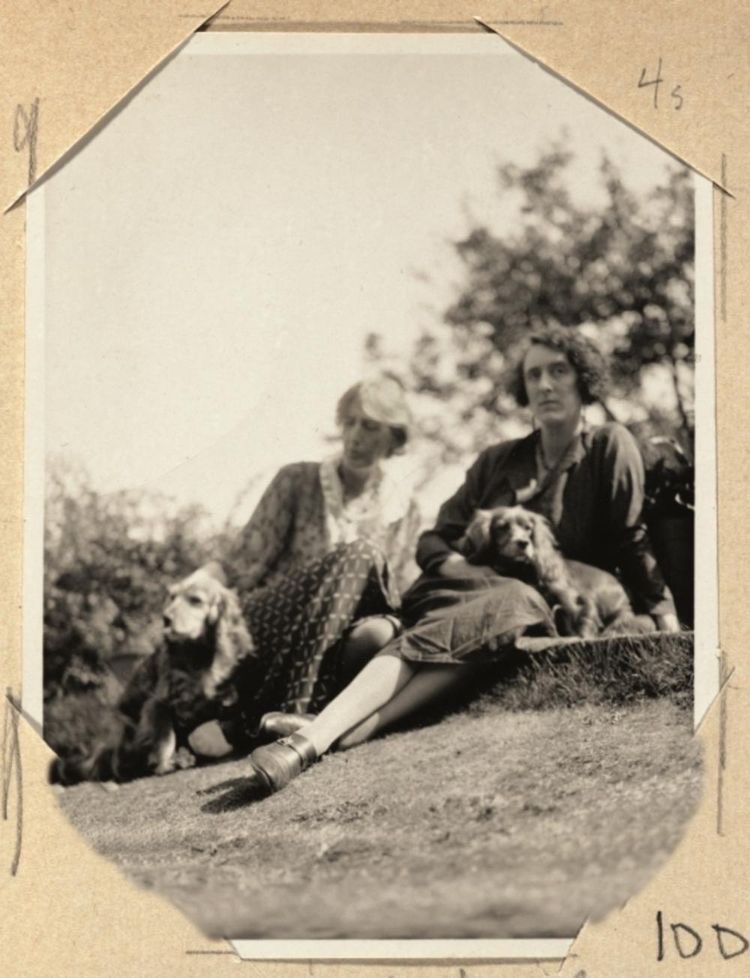

Perhaps the most sensational and most publicised of all Vita’s liaisons came next and stretched over a full decade, from 1925 to 1935: her epic love affair with eminent writer and intimidating mind, Virginia Woolf. The two met at a dinner party and what ensued is now the stuff of literary and romantic legend. Both women peaked creatively during this period as a result of their extraordinary and exponential artistic effect on each other. On other levels too, they supported one another – Vita’s effect on Virginia was therapeutic; she helped her heal from historic childhood abuse and steered her towards a healthy sexual relationship. During this time Vita published Seducers in Ecuador and The Edwardians, and Virginia published the experimental novel The Waves. Although Virginia Woolf is today viewed as the more successful of the two writers, back in the 1920s, Vita Sackville-West’s books outsold Virginia Woolf’s.

During this decade Vita often took off to Persia to visit Harold, also to Spain and France. Desperately missing her lover and alleged soulmate, Virginia wrote To the Lighthouse, a book about longing and missing a loved one. Virginia writes poignantly in her diary, “Stalking on legs like beech trees, pink glowing, grape clustered, pearl hung… There is her maturity and full breastedness … her capacity … to represent her country … to control silver, servants, chow dogs; her motherhood (but she is a little cold and off-hand with her boys) her being in short (what I have never been) a real woman.”

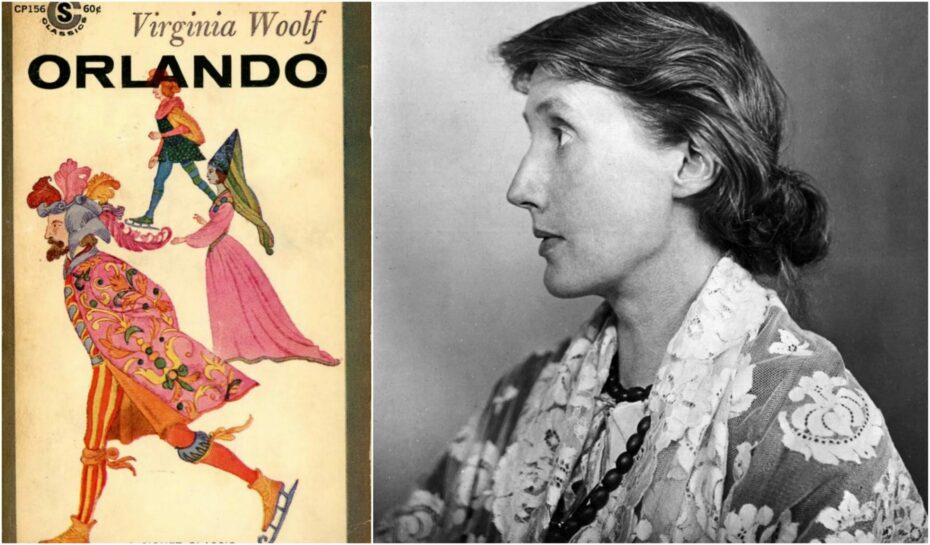

Vita inspired Virginia to write one of her best-known novels, Orlando later described by Vita’s son Nigel Nicholson as “the longest and most charming love-letter in literature”. The story of a person who changes sex over the centuries, Vita was Woolf’s real-life “Orlando”, who travels through the ages, from one gender to another until, at the end of the novel she’s portrayed in domestic bliss, at her house with her dogs. Violet Keppel, whose doomed relationship with Vita had become widespread gossip, is portrayed as a Russian princess in Orlando. Forbidden from writing directly to Vita after their separation, Keppel had continued to write desperate letters to a mutual friend before finally accepting the end of the affair and would later write a Broderie Anglaise, a piercing story, denigrating Vita and Virginia’s love affair in 1935.

Vita, however, kept up her promiscuous, free-spirited pursuit of other lovers, to Virginia’s despair. According to Dinerstein-Knight (The Paris Review, 2020), both Vita and Harold “feared that Virginia didn’t possess the emotional resilience to bear Vita’s seduction without collapse.” Cracks started to appear in the relationship. Woolfs 1929 essay, A Room Of One’s Own is a covert criticism of Vita’s unquestioning stance towards the patriarchal aristocracy and when Vita supported husband Harold’s British Union of Fascists and rearmament, Woolf chose to be the polar opposite – a pacifist. This heralded the end of their relationship in 1935. Virginia Woolf writes poignantly in her diary on March, 11th, 1935, “My friendship to Vita is over. Not with a quarrel, not with a bang, but as ripe fruit falls. But her voice saying ‘Virginia?’ outside the tower room was as enchanting as ever. Only then nothing happened.” The women did connect again however in 1937 and remained close until Virginia died in 1941.

The next chapter in Vita’s colourful life took place at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent, an Elizabethan ruin once owned by Vita’s ancestors. Both she and her ever-loyal husband Harold became involved in rescuing, designing and planting the spectacular gardens which opened to the public in 1938. Vita approached this project with as much innovative and creative gusto as she did her writing and pursuit of lovers. She experimented with novel ideas like single colour-themed gardens and gardens that gave the visitor an experience of discovery and exploration. In 1947, she commenced with a column for The Observer called ‘In Your Garden’ and kept this up until a year before her death. She made Sissinghurst one of the best known gardens in England and eventually became a founder member of the National Trust’s garden committee.

In her novel Heritage, Vita sagely proclaims, “Serenity of spirit and turbulence of action should make up the sum of man’s life,” and referring to her beloved botany she said, “You must insist upon getting a male plant, or there will not be any catkins. The female plant will give you only bunches of black fruits.” Such was her wisdom, passion and insight into both human foibles and the natural world, and the inevitable inter-connectedness of the two.

Vita died on June, 2nd, 1962 (age 70) at Sissinghurst Castle. A film ‘Vita and Virginia’ was made in 2018 starring Gemma Arterton as Vita and Elizabeth Debicki as Virginia.