There is a line in Don McLean’s Vincent, the poignant folk song released in 1971, that always stuck with me. It goes, “but I could have told you, Vincent, this world was never meant for one as beautiful as you.” The bittersweet lyrics are a tribute to the great Post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh of course, but when I became familiar with the story and work of Séraphine Louis for the first time, I could only thing of those words: this world was never meant for one as beautiful as you.

The work she has left behind is extraordinary; visionary and beautiful, but like Vincent, she also spent time in a mental asylum. She died friendless, alone and was buried in a common grave in either 1934, or was it 1942? No one can say for sure.

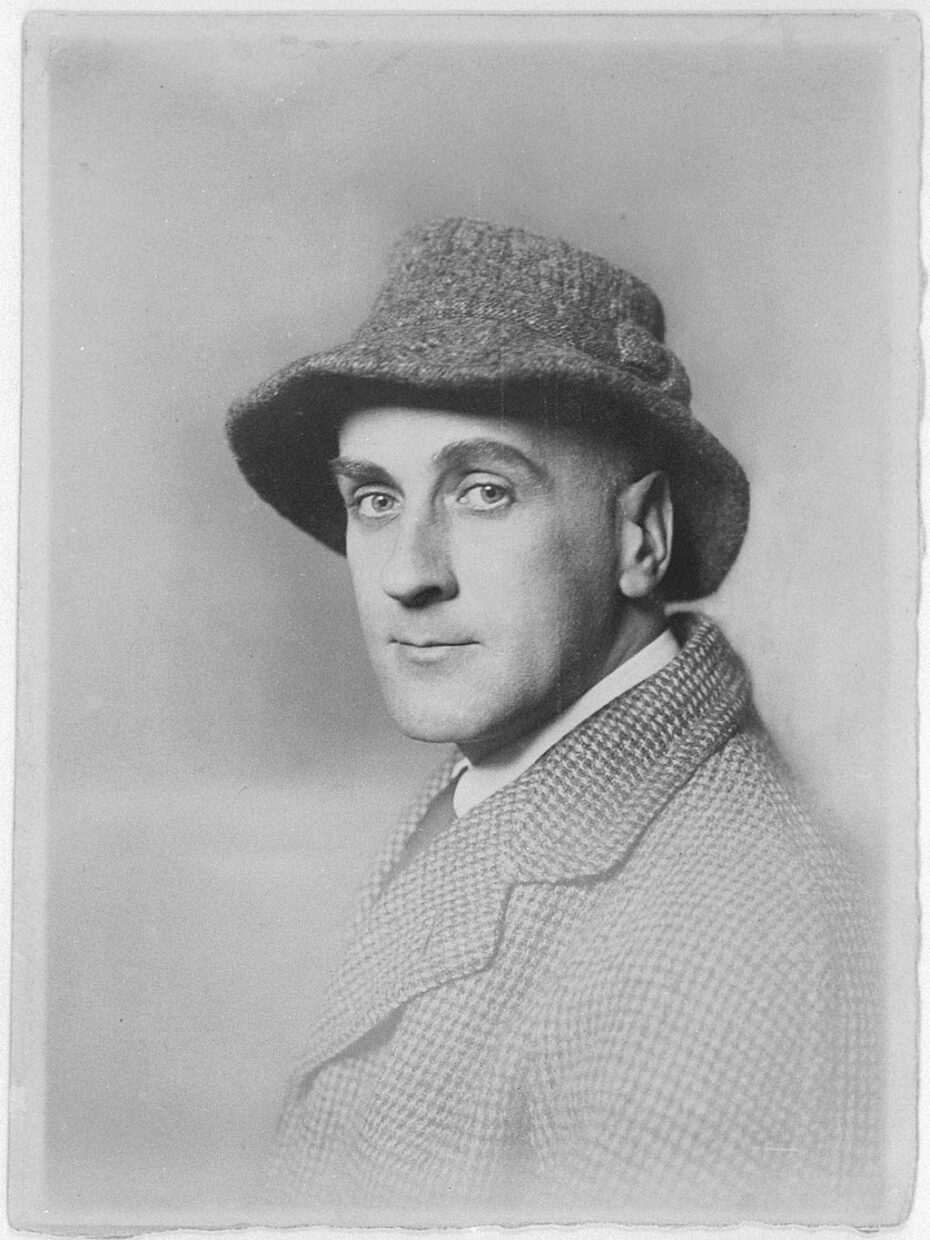

Born in 1864 in the small town of Senlis, France, she was a shepherdess, a housekeeper and did various other arduous jobs to make a living, but painted in secret by candlelight until her talent was discovered by her employer, a German art collector and critic living in Senlis. Like Séraphine, Wilhelm Uhde was an outsider. War was looming with Germany and despite being a pacifist, he was made to feel unwelcome in France. He was one of the first collectors of the Cubist paintings and purchased his first Picasso in 1905, only to have his most significant possessions later confiscated by the French government, including works by Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Henri Rousseau and Séraphine.

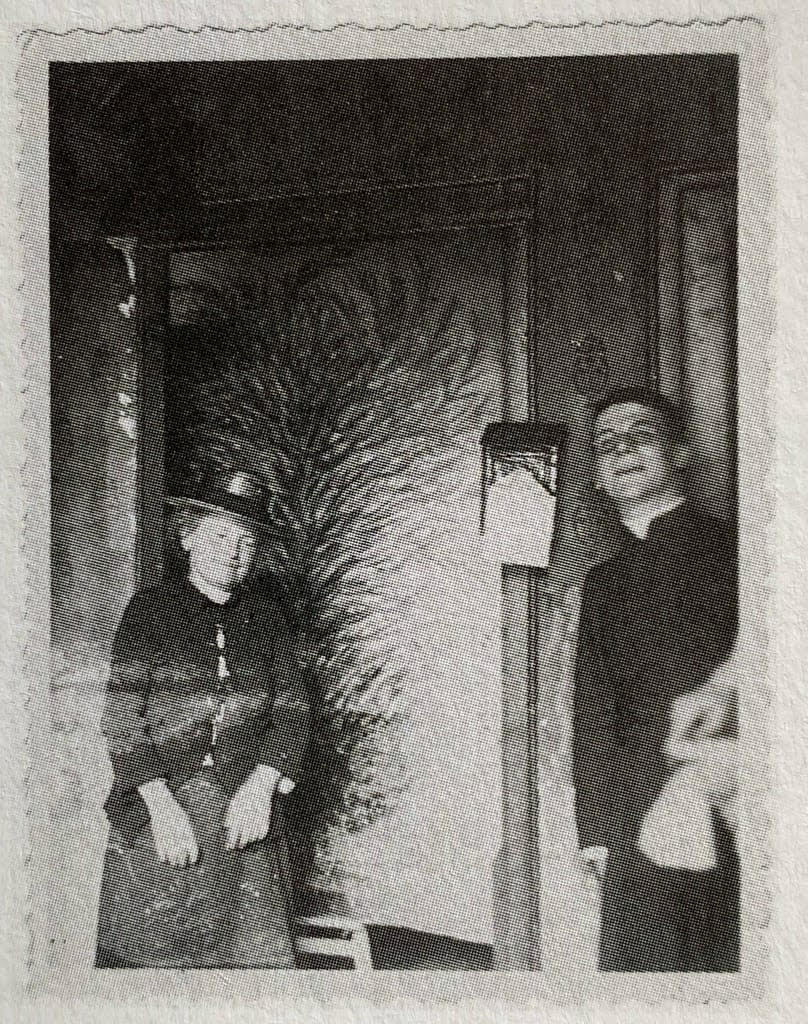

Séraphine was his cleaning his apartment in Senlis for some time before he saw one of her paintings on the wall of his neighbour’s house at a dinner party. When he discovered that his own housekeeper was the artist, he immediately confronted her and slowly, the two begin a friendship. He was immediately struck by the intensity and originality of her paintings.

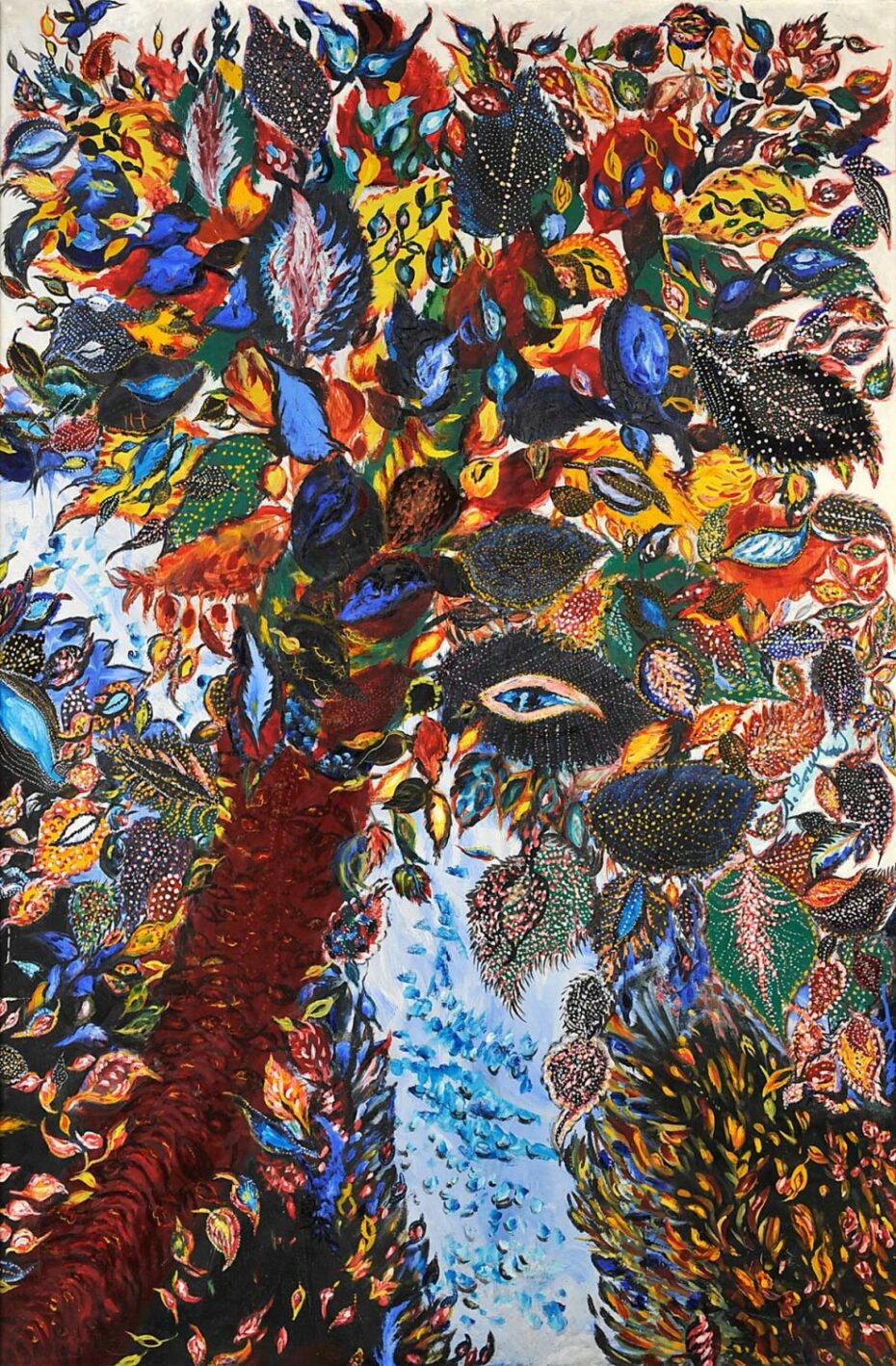

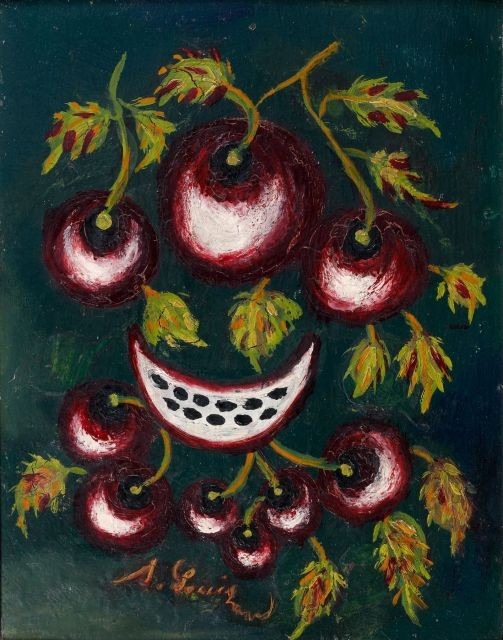

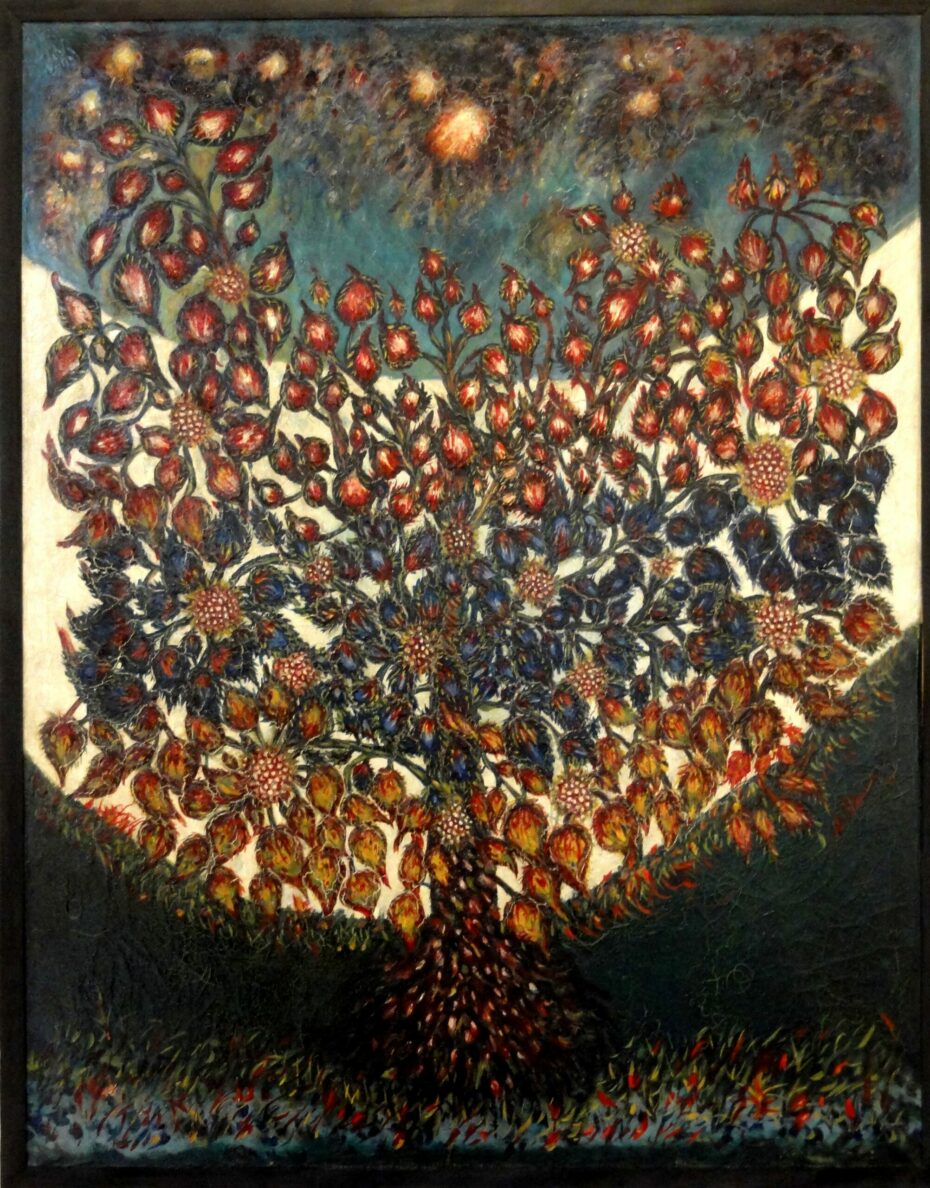

Séraphine was self-taught artist, and had developed her own unique style, characterized by her use of intense, vibrant colors and her impressionistic approach to painting. Her paintings were largely representational, often depicting nature and everyday scenes, such as flowers, fruits, and landscapes.

Under Uhde’s guidance, Séraphine began to refine her technique and some say that Uhde was the only person she ever allowed to see her paintings in progress, and that he was the only person she ever trusted with her work. He began to purchase and promote her work and would become one of her most important patrons, playing a pivotal role in bringing Séraphine’s paintings to the attention of the art world.

Séraphine’s paintings are characterized by a strong use of blues, greens, and violets, and she often used a limited palette of complementary colors to create a sense of harmony and movement in her compositions. She also used thick impasto, which is a technique of building up the paint on the canvas to create a sense of depth and texture in her paintings. Her thick impasto gave her paintings a distinctive, sculptural quality and added to the sense of movement in her compositions. Her technique was also unusual in that she would use both oil and watercolors in her paintings. She would paint in oils and then, using a watercolor technique, would add washes of watercolors on top. This combination created a beautiful and lively effects in her paintings, and helped to give them a sense of movement and spontaneity. Deeply influenced by her surroundings, she drew inspiration from the nature of the Oise region, where she lived and would often paint en plein air (outdoors), which allowed her to capture the changing light and moods of the landscape. The effects of the light and natural scenery in her work is very prominent.

Uhde introduced Séraphine to other important figures in the art world, such as André Gide and Guillaume Apollinaire, which helped to further her career. He not only purchased her works but also subsidized her living expenses, which were very limited due to her living on a very modest salary and suffering poverty.

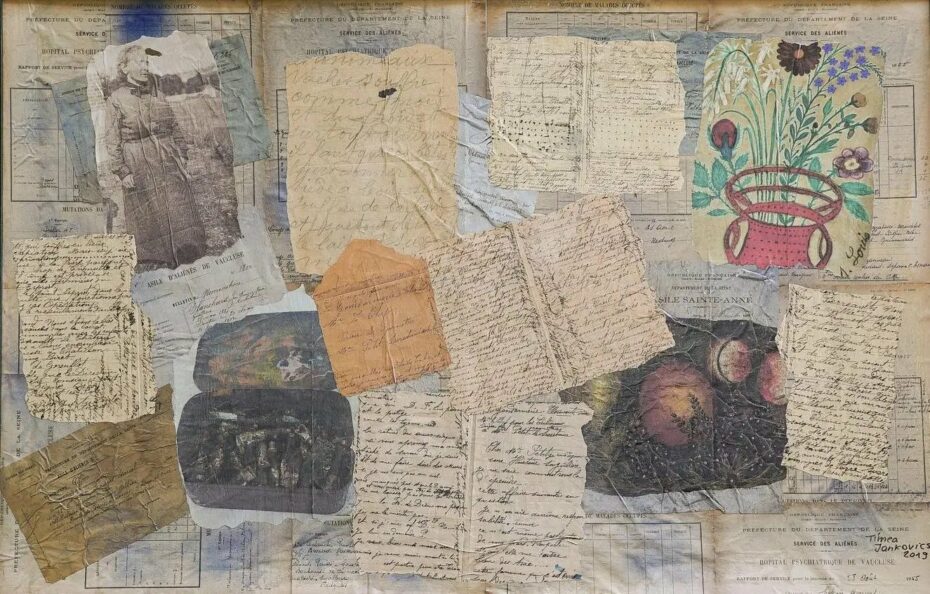

Despite Wilhelm’s friendship and support, Séraphine’s life was far from easy. She struggled with mental illness, and in 1913, she was institutionalized. After her release, she returned to Senlis where she continued to paint, but her mental and physical health deteriorated. It is not clear what her specific diagnosis was, but some art historians have speculated that she might have been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Meanwhile, Wilhelm was forced to flee France in 1914 in the middle of the night during the war between France and Germany and they lost contact. More than a decade later, he had returned to France and saw her work at an exhibition. She was still alive to his amazement, although just barely surviving after the devastation of WWI. Reunited, he resumed his patronage of her work and in 1928, organised the first Naive Art exhibition, “Painters of the Sacred Heart,” that featured Louis’s art. This drew the attention of critics and other artists and paintings were now being exhibited alongside those of well-known Impressionists such as Matisse and Derain.

With Uhde’s renewed support, her work flourished; her paintings became larger and more colourful. Praised for her unique style and intense use of color, she entered a brief period of financial success, but with her worsening health struggles, she was overwhelmed by it all and retreated into isolation once more. When the Great Depression loomed over Europe, Uhde had no choice but to stop buying her paintings and their relationship came to an end. in 1932, Louis was admitted to an asylum for chronic psychosis, where there was no place for artistry.

Uhde reported that she had died in 1934 but other accounts say that she lived until 1947. There are some reports that in 1942, during the German occupation of France, she was arrested by the Gestapo on suspicion of being a spy, when she was subsequently institutionalized again at a hospital annex at Villers-sous-Erquery, where she died friendless and alone and was buried in a common grave.

Whichever is true, we know she died in obscurity in a mental asylum, her work largely forgotten by the art world, and even by her own family. Her paintings were scattered among various private collections; some were sold by family members for a very low price, and others were lost or destroyed. A few of her paintings however, were preserved by her patrons, collectors and art historians who continued to be interested in her work. In the decades following her death, interest in Séraphine’s work slowly began to grow and her paintings started to be featured in exhibitions, retrospectives and publications. Her work was rediscovered by art historian and curator Michel Hoog, who held the first retrospective of her work in 1970 at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, which helped bring her work to the attention of a wider audience.

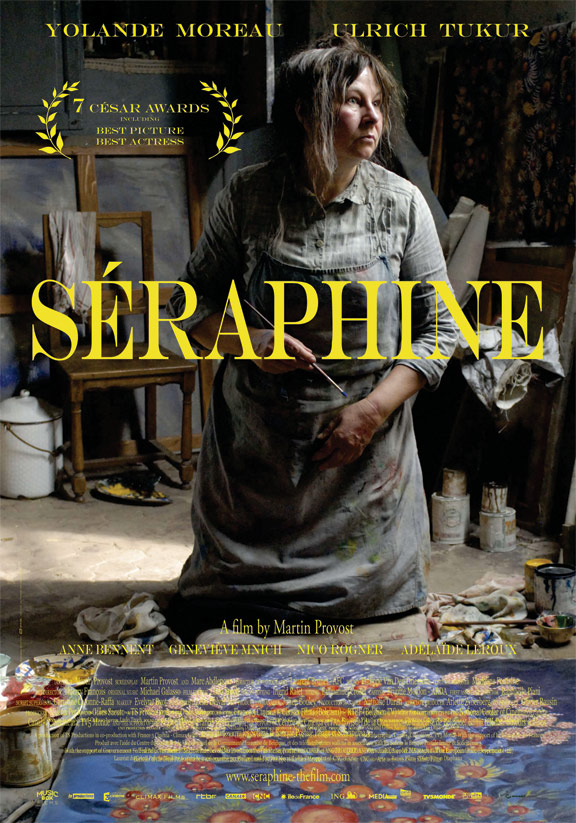

Her paintings are now considered to be some of the most important works of French Impressionism and her paintings can be found in major museums around the world, including the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. There is also a Musée Séraphine Louis in Senlis, dedicated to the artist, which holds a significant number of her works and her archives, which provide a deeper insight into her life and work. A film was made of her life in 2009, ‘Séraphine’, which won seven Cesars, exploring the relationship between Louis and Wilhelm Uhde from their first encounter in 1912 until her days in the Clermont Asylum.

Indeed Séraphine, this world was never meant for someone as beautiful as you.