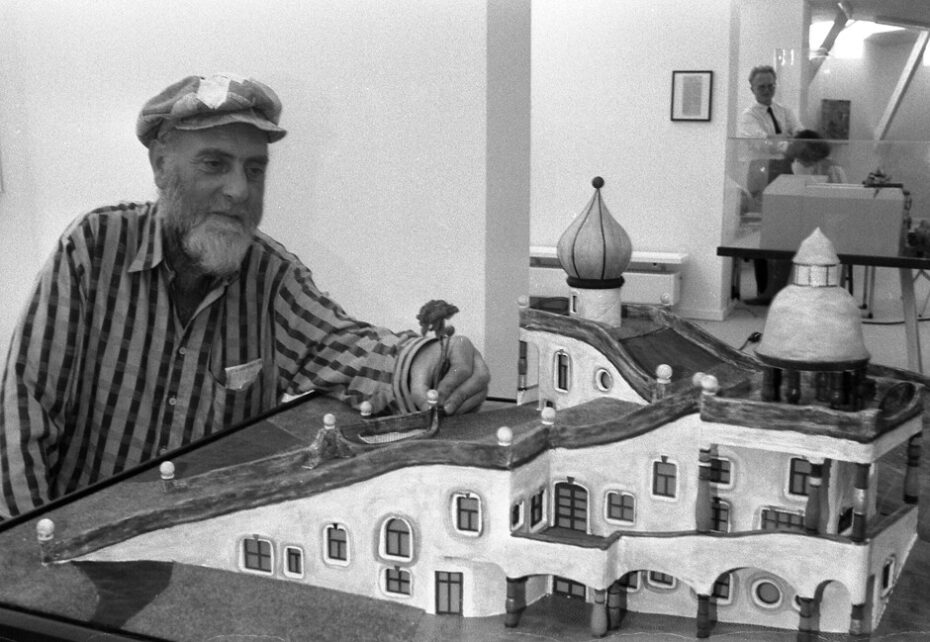

If the Emerald City of Oz had ever been in need of a new architect, he would have been just the man for the job. In his fight against the “godless line”, Friedensreich Hundertwasser’s buildings swirl into the sky with undulating curves in a kaleidoscope of colours, pierced by trees and clad with grass and reptilian mosaics. The Austrian architect’s mouthful of a name may not be a household one like Barcelona’s Antoní Gaudí, but once you see one of his buildings, you’ll be able to spot a Hundertwasser a mile away.

Let’s go back a little to get to know Hundertwasser, the man who is just as eccentric as his buildings. Born Friedrich Stowasser in 1928 in Vienna to a Catholic father (who died a year after his birth) and a Jewish mother, Hundertwasser came from a complex background as a half-Jew growing up in Nazi-era Central Europe. He was baptised into the Catholic church in 1935, took his father’s religion, and to save himself and his Jewish mother, he joined the Hitler youth to keep up Aryan appearances. However, Hundertwasser’s practising Catholicism and membership in the Hitler youth didn’t save 80 of his Jewish relatives who were killed in concentration camps.

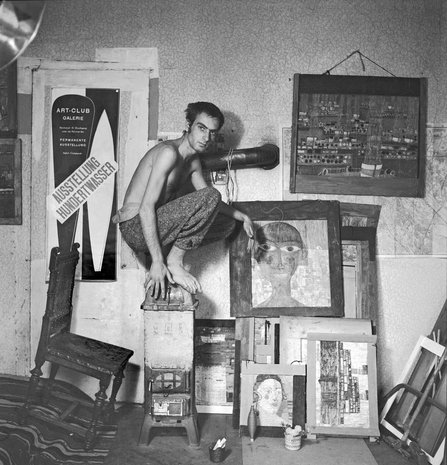

In his adult years, Hundertwasser became a painter who travelled the world over, spending extended time in France, Italy, Uganda, Japan, and New Zealand. Along with his art, he designed stamps for Cape Verde. Although he had been interested in architecture since the 1950s, he only got to build his first building in the 1980s.

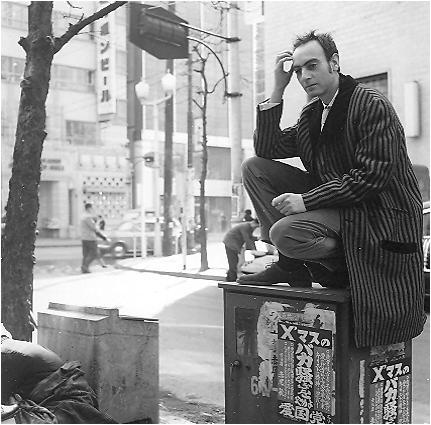

As he grew as an artist, he’d go on to change his full name into quite a mouthful: Friedensreich Regentag Dunkelbunt Hundertwasser (meaning “Multi-Talented Peace-Filled Rainy Day Dark-Coloured Hundred Waters”). He adopted the name Friedereich while he was in Japan in 1961, when he began to spell his name out in a Japanese stamp, using the symbol for peace (Friede) and rich (Reich), which eventually evolved into Friedensreich in 1968.

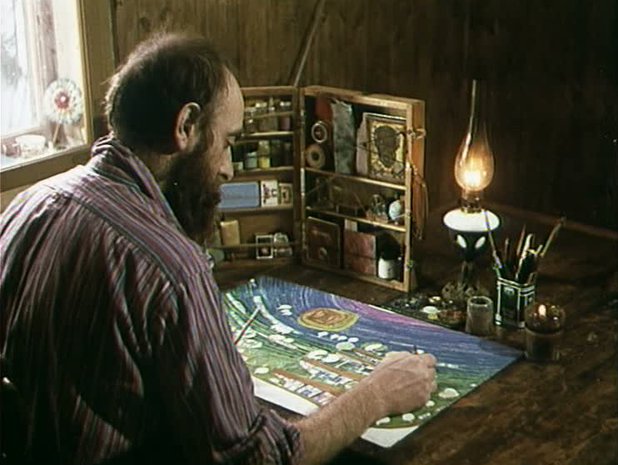

Although Hundertwasser is best known for his surreal and colourful buildings, he only turned to architecture when he was in his 50s and was better known as a painter until then. He painted canvases that already carried the blueprint for his buildings with swirling bold colours and intricate textures. However, in the 1960s, his ideas around architectural philosophy erupted when he stripped naked and gave his “speech in the nude for the right to a third skin” in Munich. His speech focused on the three skins humans have: the skin they are born with, the skin they wear as clothes, and the skin that is the facade of their houses. He penned feverish manifestos about the crimes of modern architecture, some of them on the controversial side, like the “Mouldiness Manifesto against Rationalism in Architecture,” where he criticised the straight line as being “godless and immoral.” He even advocated for people to be comfortable with mould growing in their homes.

He often liked to get naked to make his point about architecture and stripped off again just a month after Munich in Vienna at his “nude demonstration against rationalism in architecture.” Two weeks later, he called for a boycott against the predominant architecture in Vienna with yet another manifesto. In “Loose from Loos – a law permitting individual building alterations or architecture-boycott manifesto,” he attacked the concept of the straight line in architecture in opposition to the architectural ideology presented in Adolf Loos’ “Ornament and Crime,” published 60 years prior. It was also the first time he declared his idea to cover the city’s rooftops and terraces with green and trees, something that would be a core feature in his future buildings. It was a part of his architectural philosophy that “Roof afforestation is the roof cover of the future.”

Hundertwasser also advocated for sustainability, whether it was the fact he was zero-waste before it was cool (often using recycled items or rubbish in his art), or his mission to transform cities into green spaces. When he began designing buildings, he incorporated “tree tenants” in each of his structures and looked at creative ways to add nature to a building. Like Gaudí, an architect he’s often compared to, Hundertwasser loved irregular forms, organic shapes, bright colours, and mosaics.

Hundertwasser finally got the chance he was looking for to create a functional house that embodied his ecological ideals when the Mayor of Vienna commissioned him to build what is known today as the Hundertwasserhaus on the corner of Kegelgasse and Löwengasse in Vienna’s 3rd district. The building resembles a patchwork quilt of bold and pastel colours in crooked and curved lines with a tapestry of mismatched windows. More than 900 tons of soil was spread across its rooftop, and there are more than 530 trees and bushes growing from the building, and curiously, there is also a line of mosaics running through the building from the garage to the roof that spans several kilometres if you were to lie it flat. According to Hundertwasser, this line “protects the house like a stronghold. This makes it a friendly fortress, invulnerable.” Hundertwasserhaus may be his first building and certainly the most iconic, but it would not be his last.

Just a 5-minute walk away, you’ll also find the KunstHausWien perched by the banks of the Danube Canal, the only building by Hundertwasser in Vienna open to the public. Today it houses the most extensive collection of his artwork, from his paintings and graphics to tapestries and architectural plans. Inside, you can get a feel for his vision, where the floor undulates beneath you in colourful tiles.

And, if you were to sail westwards along the Danube Canal, you’d come to the incinerator plant at Spittelau, which towers above the Vienna with its 126-metre-high chimney tower gilded with a “golden plum” and has become an signature monument in the city’s skyline. It is also the cleanest and most modern waste incinerator in Europe. Although the project was challenging for Hundertwasser to take on since he advocated for a wasteless society, he figured his version would be better and cleaner than a more wasteful alternative by another architect.

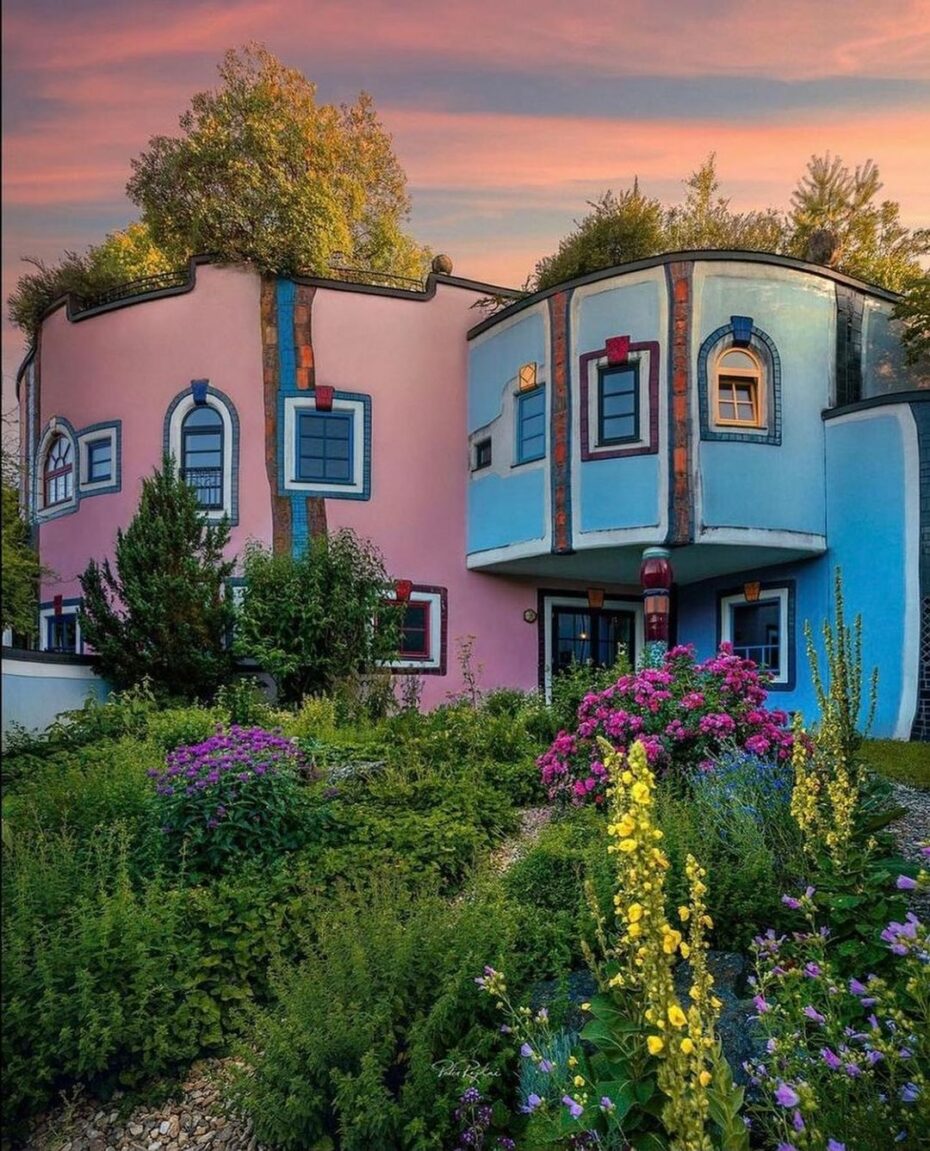

Elsewhere in Austria, his thermal spa in Bad Blumau was also a revolution in modern design. He built the spa based on the concept of rolling grass and tree-covered hills. In fact, if you were to look at Bad Blumau from above, you’d barely see it as it blends perfectly into the landscape. On the ground, the spa at Rogner Bad Blumau is an intricate labyrinth that fans out around the thermal bath with hidden oases, underground forest courtyard houses, curved and colourful walls, bridges, steps, and winding paths.

Outside of Austria, his residential building known as the Waldspirale in Darmstadt, Germany, is hidden in a back corner of the small city just south of Frankfurt-am-Main; a spectacular spiralling block of apartments. Pastel colours run through in waves, and each apartment has different handles attached to the doors and windows. The sloping rooftop is planted with grass, shrubs, flowers, and plants, while trees seem to grow out of the windows. The building is also dotted with gilded onion domes evoking Eastern European Orthodox churches.

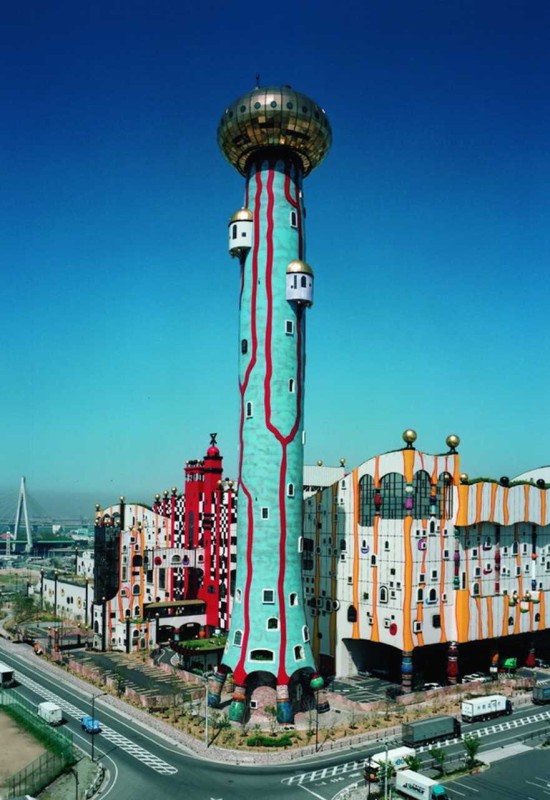

Hundertwasser’s architecture even crossed continents, with The Quixote winery in California, one of the prettiest garbage facilities in Osaka, Japan, and his final work of art, a public toilet in Kawakawa in New Zealand, which pulls in 10,000 visitors a month. There is a reason that Hundertwasser was called the “Doctor of Architecture.”

Friedensreich Hundertwasser moved to New Zealand in the final years of his life and died of heart failure aboard the Queen Elizabeth II in the middle of the Pacific Ocean on February 19, 2000. His last wish was to be buried on his property in New Zealand, naked ofcourse, and without a coffin below a tree so he could become a part of nature. “The dead do not die, but continue to live on in the form of trees,” he had once said. A tulip tree grows on its resting place in the “Garden of the Happy Dead.”