A relatively austere low-income housing complex in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, the Cité de la Muette is not a remarkable collection of buildings. At first glance, it’s a council estate like any other, where residents go about their daily business seemingly unfazed by the history that lies both within its walls and beneath them. The so-called “first skyscrapers in the Paris region”, they were also the city’s first social welfare housing complex, but sadly, that’s not why it has a museum on site. During World War II, nearly 68,000 Jews were sent here before being deported to extermination camps, serving as an internment and assembly camp under the control of the French police in collaboration with the SS during the German Occupation. Efforts over the years have worked to recenter its past, including the recent museum and several memorials, but it remains one of the littlest-known historical sites in the Paris region.

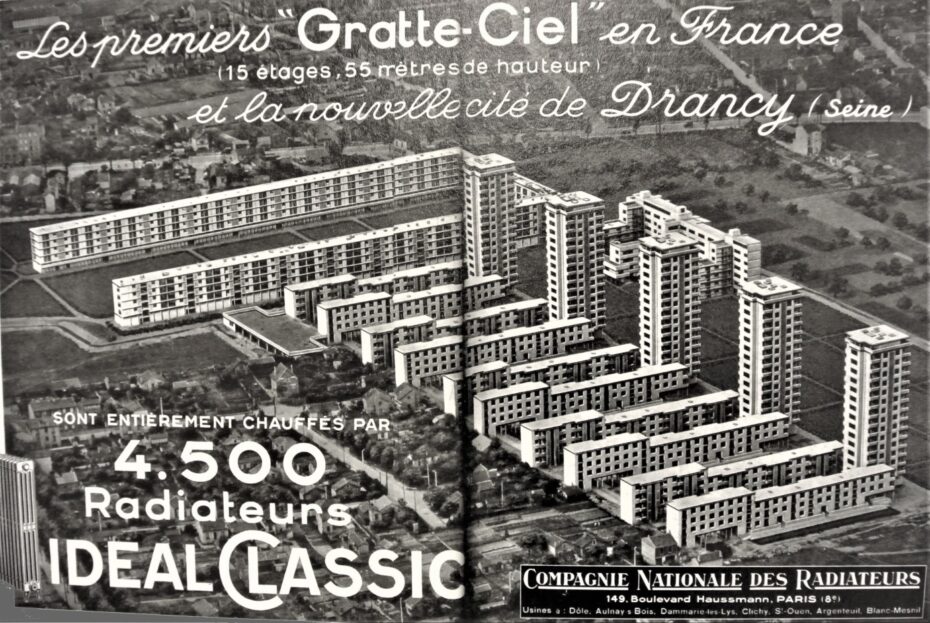

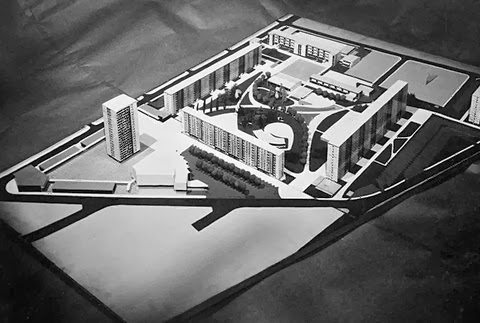

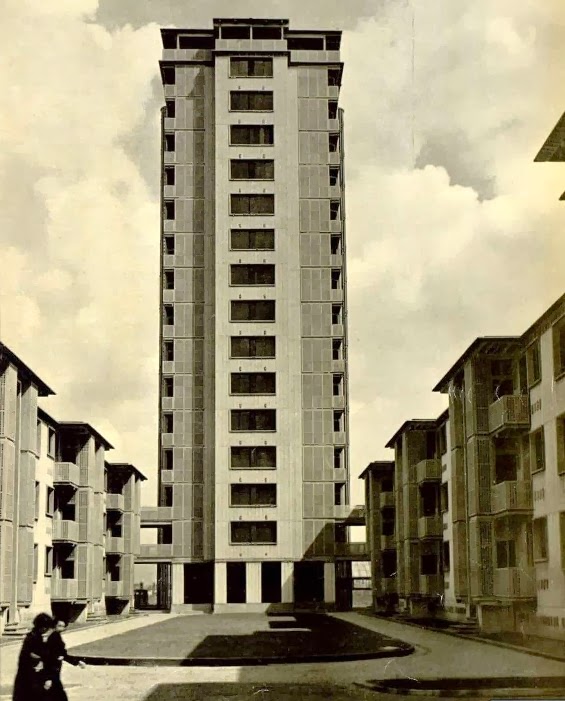

Located 11 kilometers from central Paris in the suburb of Drancy, the project was launched in 1929 and featured five 15-story buildings hosting some 1,250 dwellings, along with cultural, recreational and social amenities. The architects later added a U-shaped “horseshoe” structure to their plan. It was hailed as an architectural marvel and a pioneering social living model of the period. It was even featured in exhibits at the Paris Museum of Modern Art and the MOMA in New York. The name Cité de la Muette, which translates to “The Silent City,” was supposed to represent the peaceful urban community it was to become. But it was never actually finished.

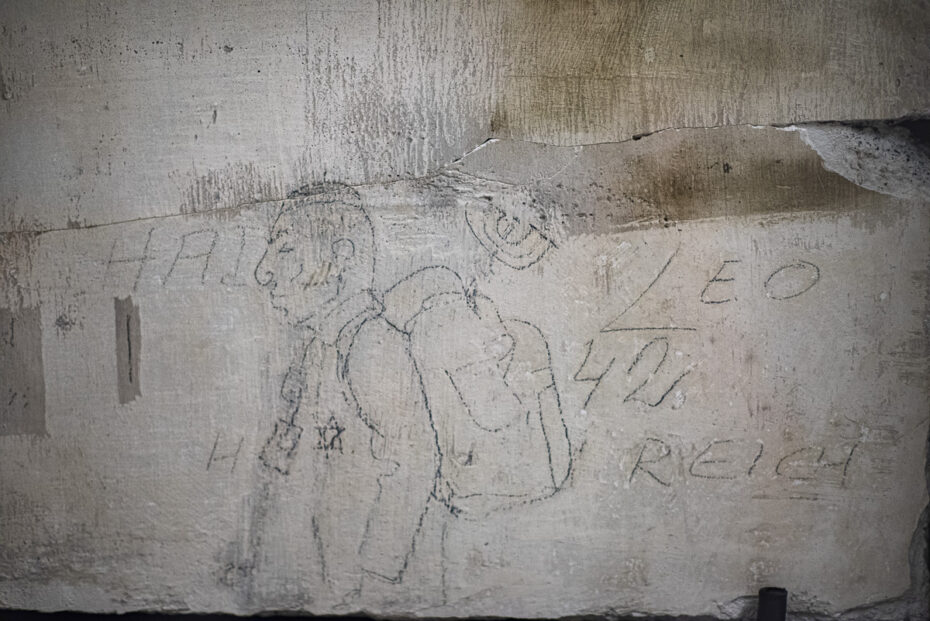

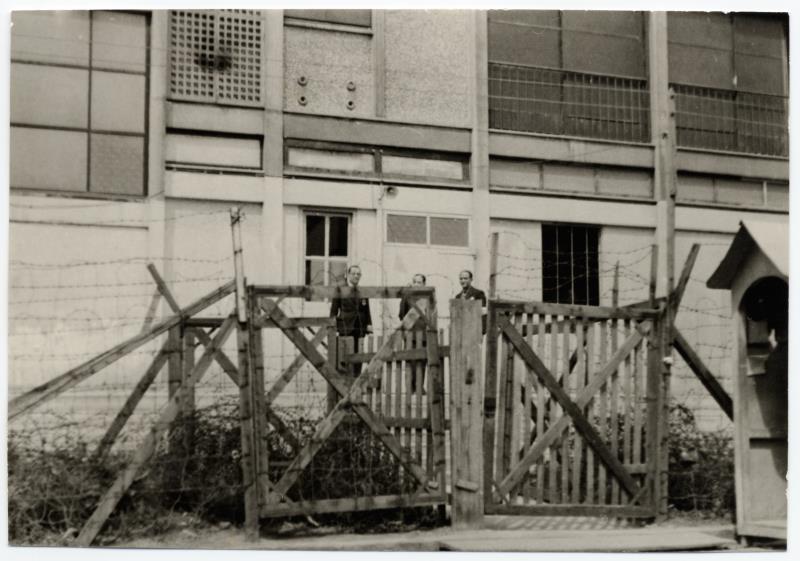

The global economic crisis hindered the project’s completion in the mid-1930s and those who had moved in complained about bad insolation and the units being too expensive. Many apartments were instead rented to law enforcement officers. The outbreak of the Second World War stopped any continued construction and after the German occupation of France in 1940, it became a police barracks. By 1941, after the installation of the Vichy Regime, the U-shaped building became a central component of the insidious deportation of Jews in France, as it was a convenient location near the Bourget-Drancy and Bobigny railway stations. The first group of 4,000 Jews was interned there in August 1941, following raids conducted by French police in the 11th arrondissement of Paris. To get a sense of the conditions, the camp was meant to house 700 people, but at its peak, there were more than 7,000.

The administrative structure and police logistics of the arrests have been little studied, with few details available. SS officers set fire to the camp’s archives before leaving, but two internees managed to save the file of names. What is known is that around 67,400 Jews of French, German and Polish origin, passed through Drancy between June 1942 and July 1944, including some 6,000 children. They were transported to concentration camps by 64 rail transport trips. There were efforts at resistance. People living in the camp started building an underground escape tunnel but it was discovered before being finished.

Many had been taken in during the Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup, a mass arrest of foreign Jewish families by French police under instruction from German authorities. According to official police records, 13,152 Jews in Paris were arrested between July 16 and 17 of 1942 and taken to the Vélodrome d’Hiver (“Winter Stadium”), an indoor bicycle racing track located not far from the Eiffel Tower. Kept in crowded, unsanitary conditions, they were then sent to the Cité de la Muette as well as concentration camps in Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande. Many were deported to Auschwitz.

One of the most famous people who lived in the camp was Simone Veil, the pioneering politician who would go on to support women’s rights, including legalising abortion as French health minister. Veil, who passed away in 2019, also served as president of the European Parliament. But while celebrating the completion of her baccalaureate exam in her hometown of Nice, she was arrested by the Gestapo. Veil, as well as her mother and sisters were eventually sent to Auschwitz, with Veil only surviving by lying about her age. She and her two sisters survived, but the rest of the family perished. Her story was told in the 2022 film “Simone Veil, A Woman of the Century.”

As the Allies advanced in the early summer of 1944, thousands of Jews were brought from the South of France to Drancy. Only around 1,500 people were still in the camp after German authorities fled and it was handed over to the Red Cross. Alois Brunner was an Austrian SS officer in charge of the camp as well as other deportation operations around Europe. Brunner was responsible for sending over 100,000 to the camps. He was condemned to death in absentia in France in 1954 for crimes against humanity, but he evaded capture in Syria for the rest of his life, likely dying in 2001.

As for the Cité de la Muette, it continued to be used as a place of internment after liberation but now for Nazi collaborators. By 1946, it went back to low-income housing. Between the 1950s and the 1980s, the Holocaust gradually seeped into France’s historical consciousness. Survivors began speaking up, although few listened to them, and organisations campaigned to build a memorial in Drancy.

The first was a 1977 sculpture by Holocaust survivor Shelomo Selinger. The design features three blocks that form the Hebrew letter shin ש, which is traditionally attached to the door of Jewish homes. The two side blocks represent the doors of death, with Drancy being considered “the antichamber of death.” The centre block features 10 figures, the number needed to form a prayer group, which are being suffocated by the flames of remembrance.

Railway tracks, known as the path of the martyrs, lead to a freight car that once transported 100 people at a time to the gas chambers. The original 1940 car, clearly marked with France’s state-owned railway company logo, was donated to the site by the SNCF, which unbeknownst to most train travellers commuting around the country as we speak, was the very same company to deport the internees out of Bourget-Drancy to the death camps.

In 2001, the area was included in the list of protected sites and monuments in France. A Holocaust memorial museum was opened in 2012 by then president François Hollande. The museum tells this horrific history through the testimonies of those who were deported in a building designed by Roger Diener. The modern design is a nod to the architectural innovation that was behind the original project, while its towering height gives a sense of the graveness of internment.

Today, the remaining residence is filled with families who have requested social housing and are placed there without knowledge of its past. But an engraving on the monument encourages taking a moment to pause and remember this dark past: “Passers-by, reflect and do not forget.”