Picture the scene back in 1937, during the heyday of American jaunts down to Cuba, when the first Pan Am seaplanes regularly took pleasure seekers from Key West to Havana: a group of hard drinking, ex-pat newspapermen are ensconced in the bar of Havana’s grandest hotel, the Nacional, discussing the finer point of sports and cocktails.

A gang of us were lolling about the Nacional Hotel Bar listening to señor Joseph Hergesheimer, the very sophisticated American novelist, giving off an erudite lecture about Carl Hubbell, the New York Giant’s pitcher…when somehow or other the general conversation drifted to the subject of drinking. And without a dissenting voice it was agreed that drinking was Cuba’s National Sport.

– Jack Cuddy, United Press reporter, Cuba, 1937.

For a few decades prior to the Revolution, gambling mobsters such as Meyer Lansky turned Cuba into a Las Vegas style playground in the Caribbean, teeming with casinos, saloons and bars. Fast forward eighty something years and we ventured down to Cuba to see what it’s like to go a-cocktailing at night in old Havana, a city largely frozen in time since the 1950s; a beguiling place that travel writer Brendan Sainsbury neatly sums up as, “timeworn but magnificent, dilapidated but dignified.” Along the way we’ll drop by the bars where Hemingway still holds the record for cocktails in one session, where Graham Greene set his seminal 1958 spy novel, Our Man in Havana, and explore the origins of the holy trinity of Cuban cocktails, the daiquiri, the mojito and the Cuba libre.

Havana, like every capital city, is packed with bars. So where to begin our adventure in search of Cuba’s best picker uppers and restoratives? Luckily our intrepid band of pressman back at the Nacional in 1937 did most of the legwork for us. Jack Cuddy picks up the tale:

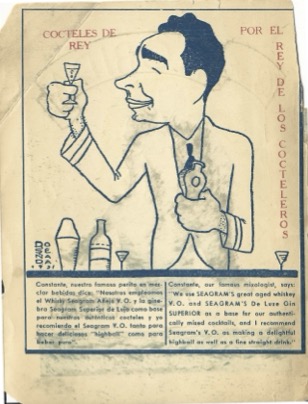

“We first learned about the king pin of Cuban drink dispensers when our bartender at the Hotel Nacional whispered the name of Ribalaigua. Then we sent a committee of one to make a telephone poll to Sloppy Joe’s, the Plaza, the Sevilla and Prado 12. He returned and said the bartender was right. The vote was unanimously in favour of Constantino Ribalaigua.”

Constantino Ribalaigua was known with good reason as El Rey de los Coteleros, the Cocktail King of Cuba; he held court at the bar he owned at the far end of Calle Obispo, the grand, two hundred year old El Floridita, and there he invented the legendary daiquiri.

Of recent years the daiquiri cocktail has lost its way somewhat; places that do serve them, offer up a kind of adult slushy dispensed with fruit from a giant blender behind the bar. But the traditional daiquiri is a simple elegant affair of just rum, fresh lime juice and sugar presented in the sort of demure glass you’d get a dry martini; in essence, perfect for warm climes.

In December 1959, Esquire magazine rated El Floridita as one of the seven most famous bars in the world, placing the historic Havanan watering hole alongside other luminaries, the 21 Club in Manhattan, Raffles in Singapore, the Ritz bars in both Paris and London, the Shelbourne Hotel bar in Dublin, and the Pied Piper in San Francisco, an honour that still stands up today. From the magnificent mural of old Havana harbour behind the bar, to the elegant red blouson jackets of the staff, Constantino Ribalaigua called his bar, “a refuge of art and beauty….that still stands (after two hundred years), serving the public, business men, politicians, professionals, writers and the most beautiful of elegant women.” Step inside El Floridita today to discover a lush oasis away from the dust and noise of Old Havana.

To give you an idea of what delights await inside for the weary traveler, here’s a review from 1937, and like most things in Havana, not much has changed since:

“As the modern cocktail is said to be the poetry of liquor, its essence and fragrance is that of a subtle flower. The delicate crystal of the cocktail glass enables you to enjoy all the good that exists, leaving the hardship of daily life forgotten. The art of the cocktail remains, as did the ancient culture in Europe during the invasion of the barbarians, safely revered in its most sacred temples, viz: the American Bar in Paris, and the Floridita in Havana, Cuba.”

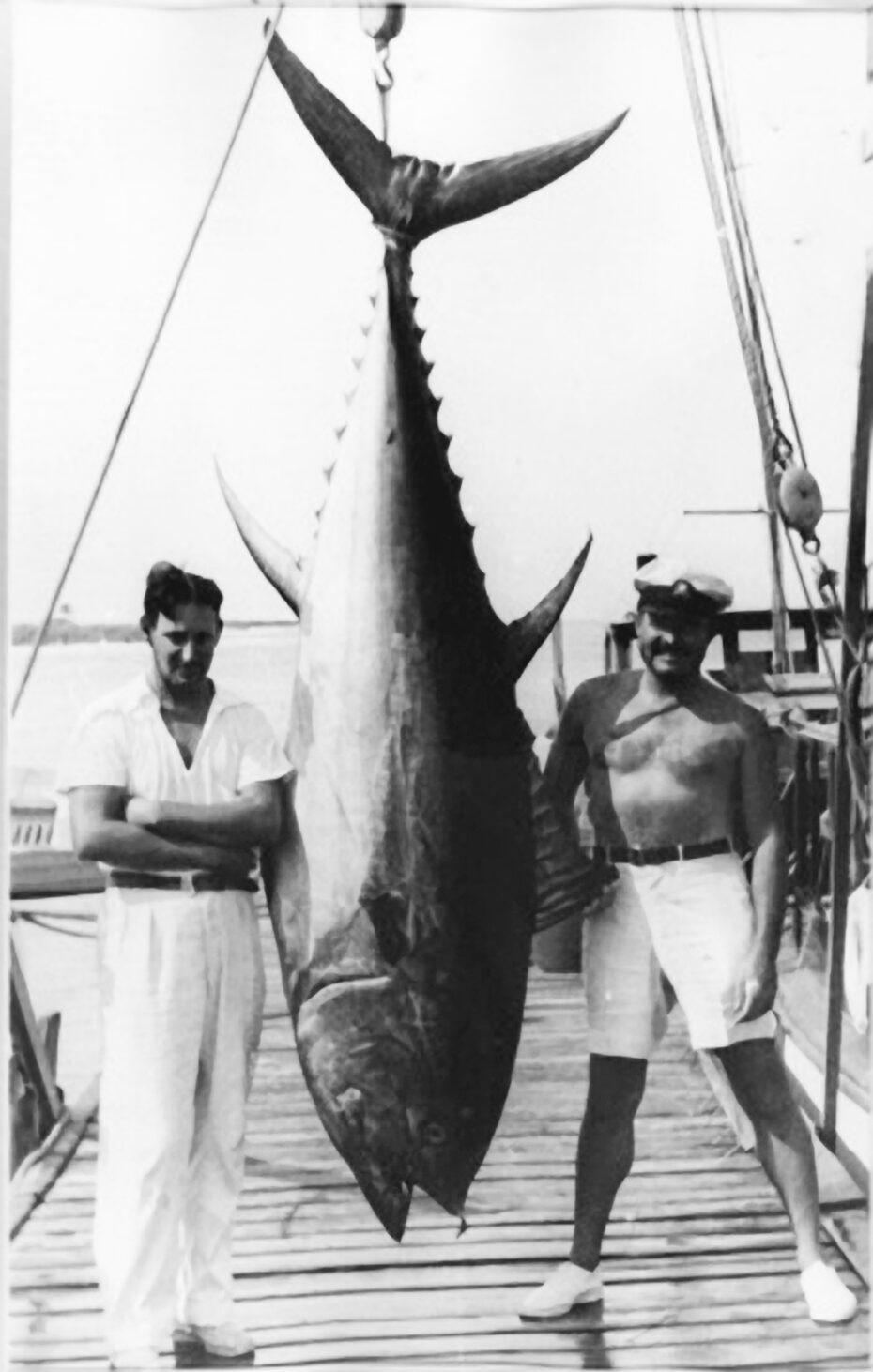

Like most cocktails, the exact historical origins of the daiquiri are unknown. Charles H. Baker the travel writer and deep-sea fishing buddy of Hemingway wrote in his 1939 book, ‘The Gentleman’s Companion: Being an Exotic Drinking Book, or Around the World with Jigger, Beaker and Flask,’ that, “We honestly believe that more people have boasted about the origin of this happy thought than any modern drink that dates from the Spanish-American War. In those days not one American in 10,000 had ever heard of Ron Bacardi, much less invented drinks with it.”

For Baker, the most likely story was traced to two American mining engineers, Harry E. Stout and Jennings Cox, toiling away in the heat of the mountains outside of Santiago, on the south east coast of Cuba. With yellow jack malaria rampant, the pair decided to clean up the drinking water, by first boiling it, then adding rum, limes, and a little sugar, before chilling the mixture with ice. They named their hopefully healthier drink after the nearby village of Daiquiri, and given the abundance of its ingredients to be found in Cuba, the cocktail became wildly popular, although Baker warned, “remember please, that the too-sweet daiquiri is like a lovely lady with too much perfume.” But as the drink spread throughout Cuba, it was undoubtedly perfected by Constantino Ribalaigua, where it made El Floridita so famous it became known as ‘La Cuna del Daiquiri’, the ‘Cradle of the Daiquiri cocktail.’

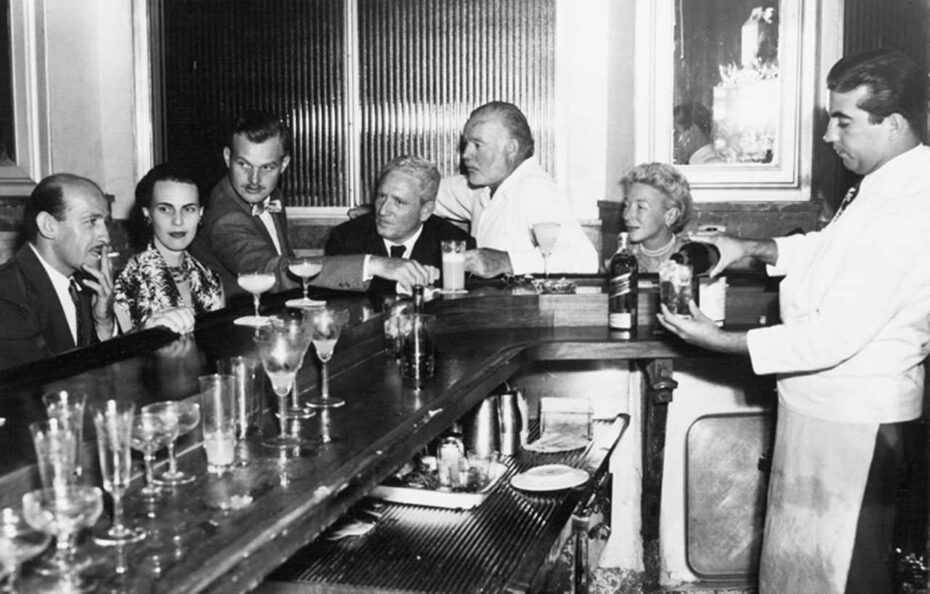

The presence of Ernest Hemingway looms large at El Floridita, literally: there’s a magnificent full size bronze statue of the writer in his favourite corner, leaning against the bar. Hemingway began coming to El Floridita in 1932, when he was staying the Ambos Mundos Hotel, working on the From Whom the Bell Tolls in room 511. His usual writing pattern was to rise early, and write from dawn til noon, when he would venture out to Havana’s bars or fish for marlin from his boat Pilar which he kept moored in the harbour. And more often than not, Hemingway would end up at El Floridita. In his excellent guide to Hemingway’s drinking habits, “To Have and Have Another – A Hemingway Cocktail Companion,” Philip Greene writes how Hemingway, afraid of the onset of diabetes, had Ribalaigua tweak his famous recipe, swapping out the sugar for maraschino and adding extra rum: “compounded of two and a half jiggers of Bacardi White Label rum, the juice of two limes and half a grapefruit, and six drops of maraschino, all placed in an electric mixer over shaved ice, whirled vigorously and served in large goblets.”

Named in his honour, ‘the Papa Doble’ made its way to the cocktail menu of El Floridita, and was lovingly described in his posthumously published, “Islands in the Stream”; “The great ones Constantino made, that had no taste of alcohol and felt, as you drank them, the way downhill glacier skiing feels running through the powder snow and, after the sixth and eighth, felt like downhill glacier skiing feels when you are running unroped.”

Hemingway still holds the record for Papa Dobles consumed in a single session at El Floridita; an astonishing 17 of the fearsome frozen elixirs, which he consumed alongside two steak sandwiches before going fishing in the afternoon.

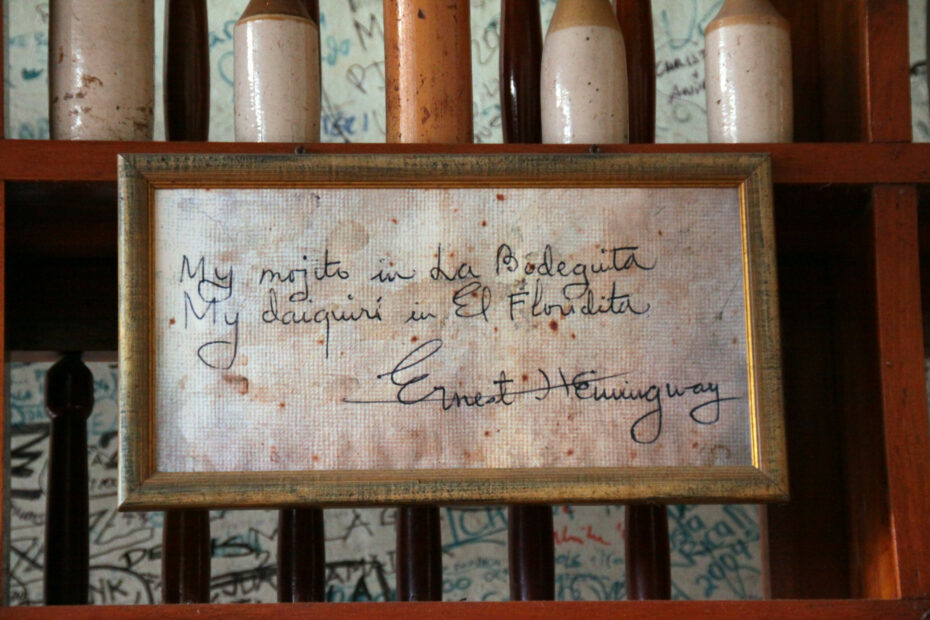

We’re continuing to follow in the footsteps of Hemingway with our next pitstop, La Bodeguita del Medio, where behind the bar you’ll find a framed napkin. Supposedly signed and hand written by Hemingway, it states, “My mojito in La Bodeguita. My daiquiri in El Floridita”.

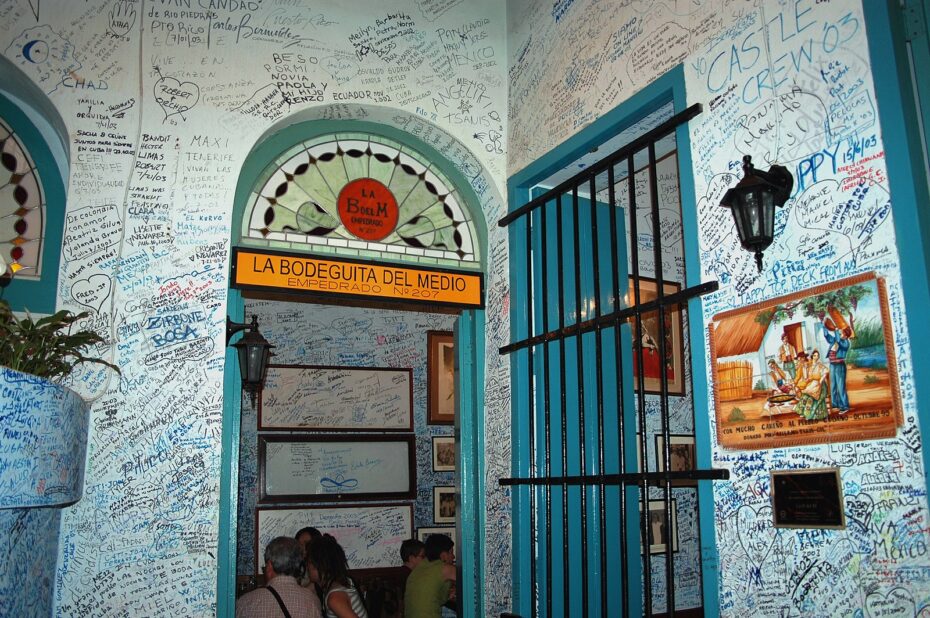

Sound advice as we explore the second of Cuba’s iconic cocktails: the mojito! Perhaps more of a punch than a cocktail, this refreshing mixture of white rum, sugar cane juice, lime juice, soda water and mint is thought to have first appeared on the drinks menu as far back as the 16th century. One legend has it that Sir Francis Drake, arriving in Havana harbour in search of Spanish gold, sought a medical cure for the scurvy that ailed his crew. Guided by the local inhabitants, a tonic was created using aguardiente de cana (firewater of the sugar cane), mint and the juices pressed from the sugar canes and limes. The restorative took off and became known as ‘El Draque’. But whatever the exact origins of the now wildly popular summer drink, it was perfected at La Bodeguita del Medio.

Located on Calle Empredrado in the heart of Habana Vieja, just steps away from the Plaza de la Catedral, La Bodeguita del Medio opened in the 1940s as a convenience store, hence the name, before its signature drink, the mojito, turned the small bar into a staple of Havana’s nightlife. The walls of the cramped bar are covered with signatures and photographs of past glamorous clientele, such as Marlene Dietrich, Brigitte Bardot and Nat King Cole, and the old wooden bar is lined up with rows of as many forty mojitos, the mint being constantly muddled by the expert bar tenders.

At times the bar will flood with tourists, but you’re still more likely to find locals here than at El Floridita, and the cosy friendly confines are filled with cigar smoke and the sounds of a four-piece band tucked into the corner. There is some debate as to whether Hemingway actually spent much time drinking mojitos at La B del M, given his aversion to sugary drinks. Whilst researching his Hemingway cocktail guide book, Philip Greene could find no account of Hemingway ever mentioning a mojito once in any of his books. You can find cheaper mojitos in bars throughout Havana, but perhaps none will be as atmospheric as La Bodeguita del Medio.

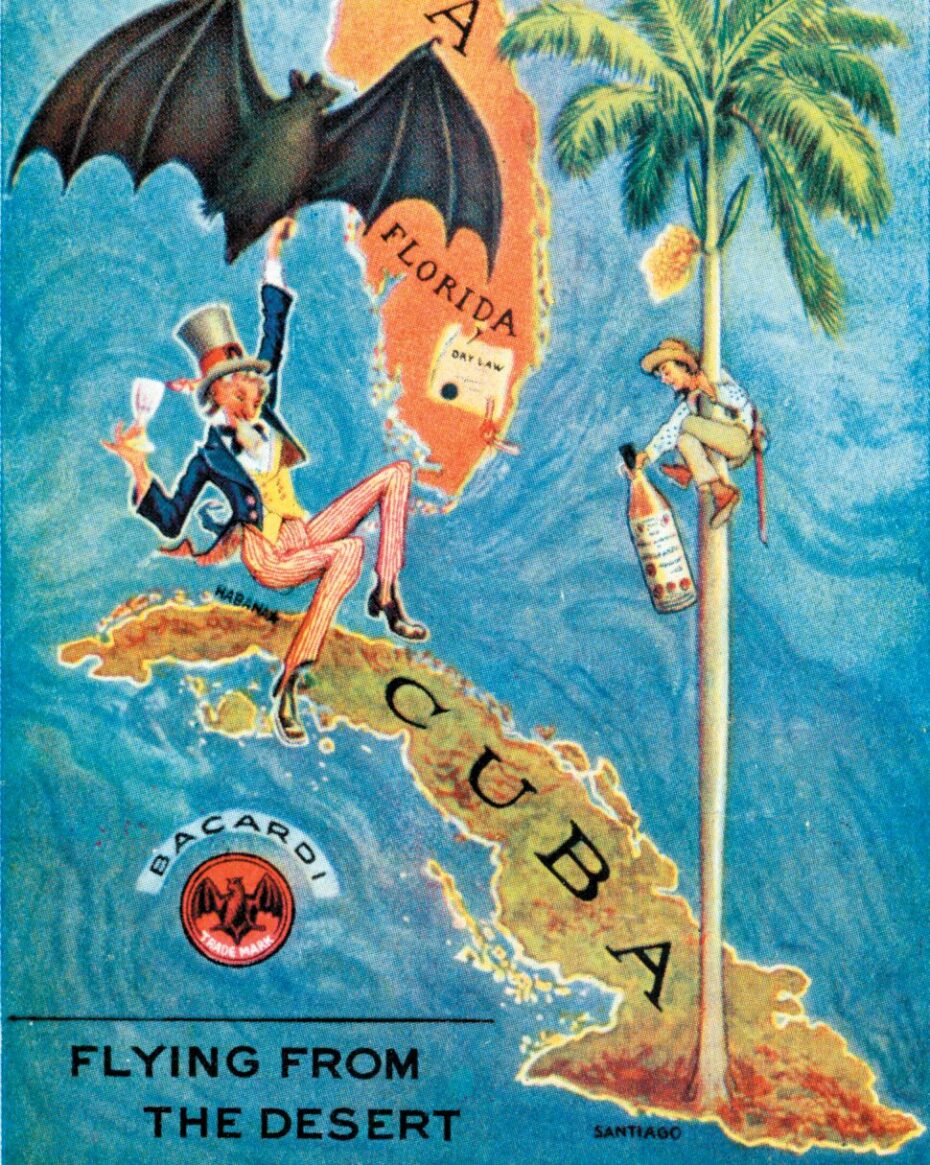

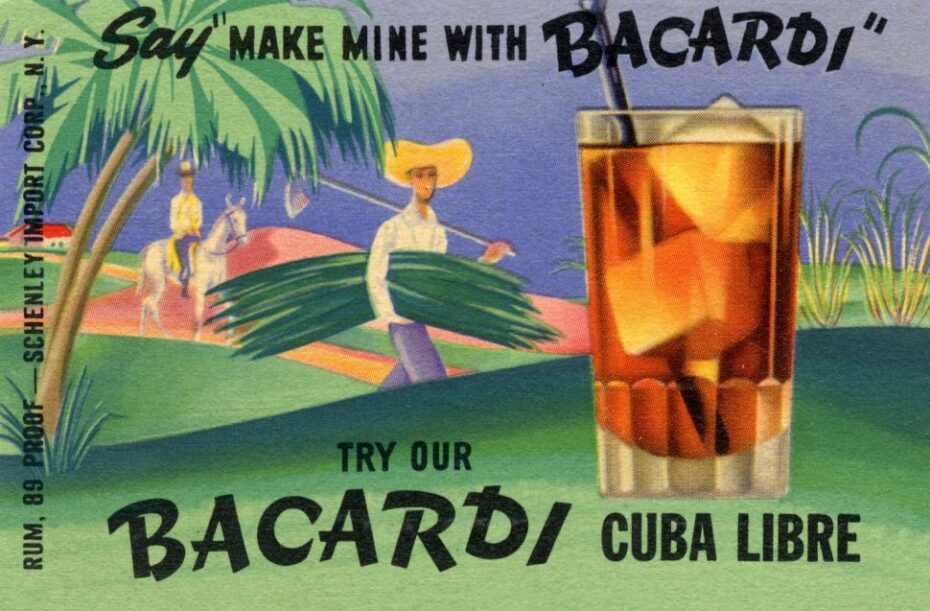

Our final classic Cuban cocktail might be the most simplest in terms of ingredients, but probably has the most history: the Cuba libre! Consisting just of Coca-Cola, Bacardi rum and a slice of lime over ice, the Cuba libre is thought to date back to the Spanish-American War of 1898. After the USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbour, the United States sent troops to back the Cuban rebels fighting to overthrow their Spanish colonial rulers.

After Independence was won 1895, US influence bloomed throughout Cuba, and as cruise ships and warships flocked to the island, so to did thousands of cases of Coca-Cola, and it wasn’t too long before the soft drink was readily mixed with Cuban rum. As to who was first to come up with the rum and coke is hard to pin down. One story has the refreshing drink attributed to a US Army Signal Corpsman, Fausto Rodriguez, although his later job as Bacardi’s director of publicity in their Manhattan office might play a part in that particular tale. But as Philip Greene notes in his Hemingway book, “Coca-Cola arrived around 1900, and when folks took to mixing rum and Coca-Cola together, with a healthy wedge of lime, they’d raise their glass and toast to a free Cuba……Por Cuba libre!”

With its historical pedigree, fervent rallying cry, and most of all, readily available cheap ingredients, the Cuba libre quickly spread throughout Cuba’s drinking spots and abroad. But our resident literary experts gave the drink short shrift: Charles H. Baker critiqued, “this native island concoction started by accident…..the only trouble with the drink is that it started by accident and without imagination, and has been carried along by the ease of its supply. Under any condition it is too sweet.”

Perhaps the most damning criticism of the Cuba libre occurs in Hemingway’s 1937, To Have and Have Not. American tourist Mrs Laughton, “blonde curly hair cut short like a man’s, a bad complexion, and the face and build of a lady wrestler” enters Freddy’s Bar in old town Havana, in search of refreshment, as does the main character, Harry Morgan.

“What will you have?” Asked Freddy. “What’s the lady drinking?,” Harry asked. “A Cuba libre.” “Then give me straight whiskey.”

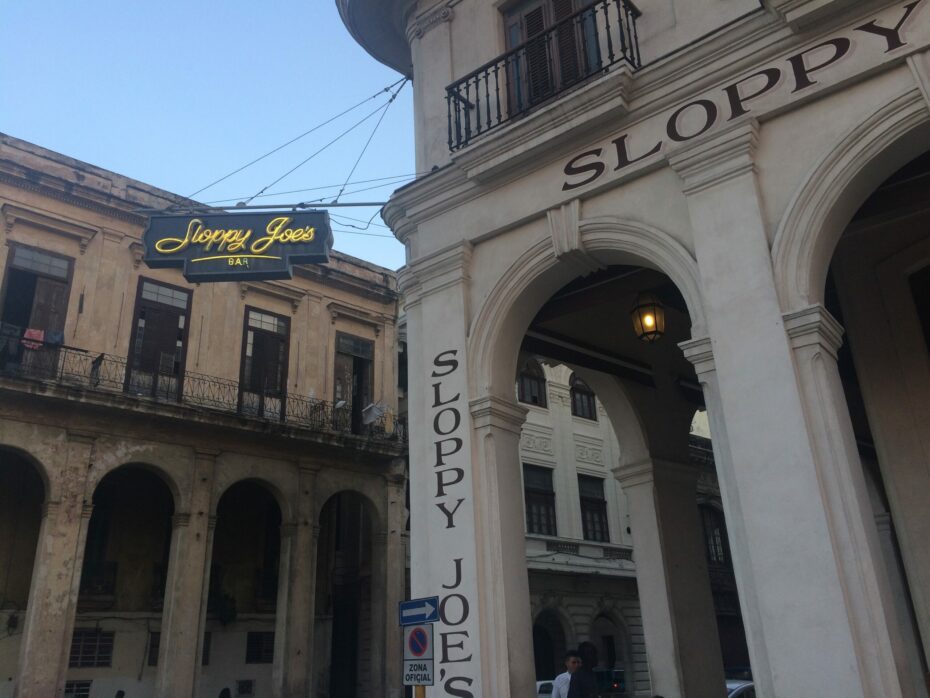

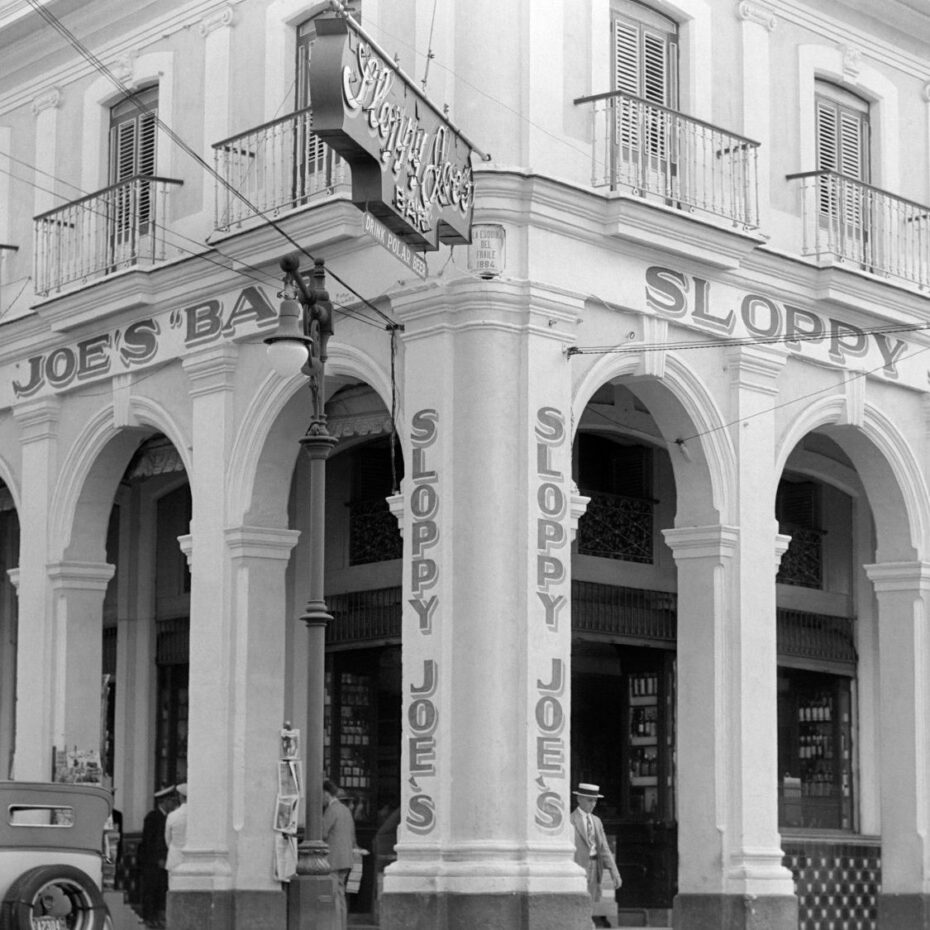

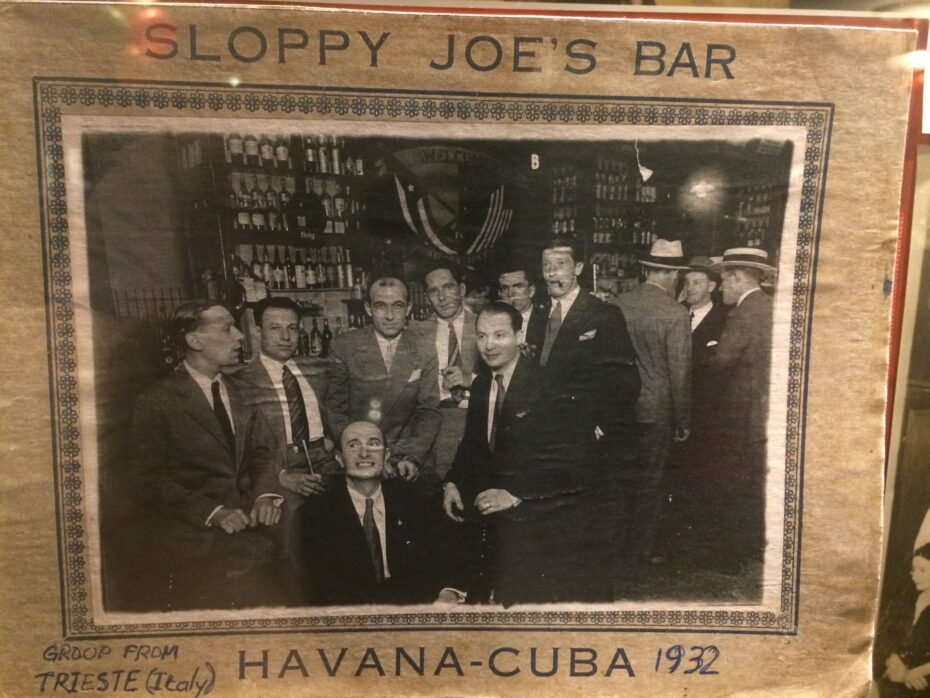

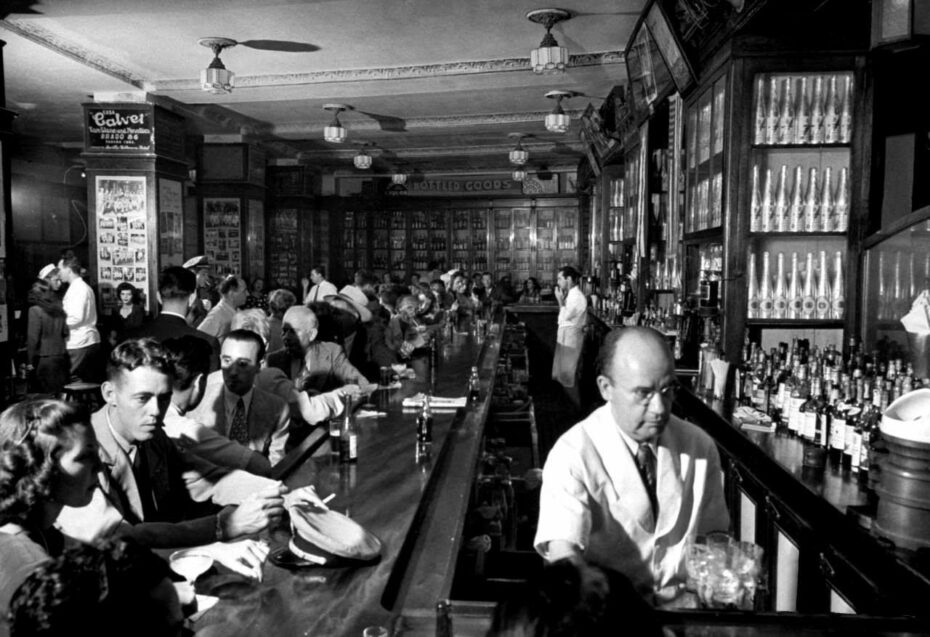

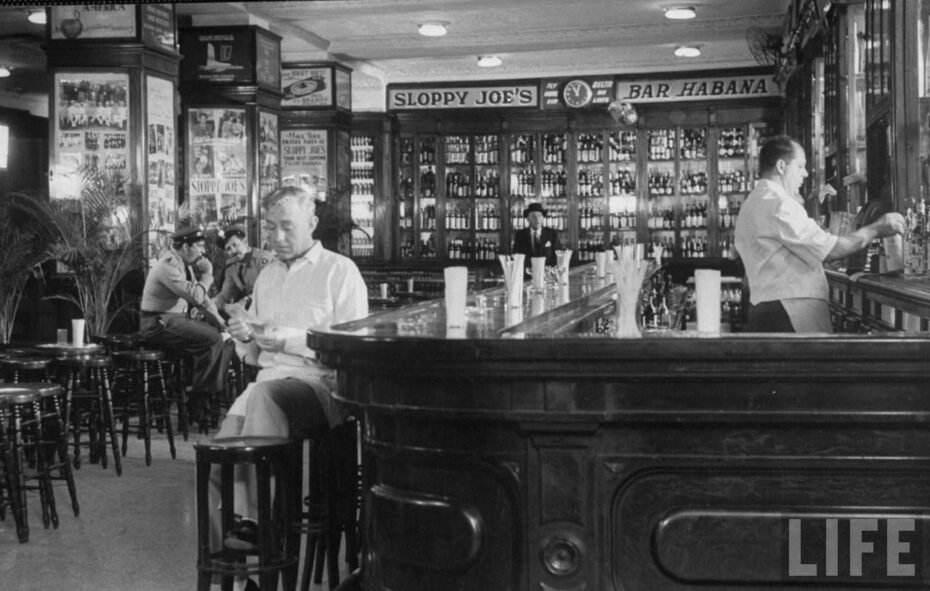

Hemingway based Freddy’s Bar on our last pitstop, the legendary Sloppy Joe’s. A grand, neo-classical building located a block from the wide, European style boulevard of the Paseo de Martí, that divides Old Havana from the sprawling tenements of the Centro neighbourhood. Sloppy Joe’s boomed during Prohibition as Americans flocked to Cuba in search of casinos and cocktails. Its 60-foot long bar and sumptuous Spanish Colonial design became an oasis from the sweltering heat, the Los Angeles Times once describing Sloppy Joe’s as enjoying“the status of a shrine.”

The bar played a key location in Graham Greene’s 1958 spy novel, Our Man in Havana: it is where the hapless hero James Wormold is recruited by the British secret service. “For some reason that morning he had no wish to meet Dr. Hasselbacher for his morning daiquiri… so he looked in at Sloppy Joe’s instead of at the Wonder Bar. No Havana resident ever went to Sloppy Joe’s because it was the rendezvous of tourists; but tourists were sadly reduced nowadays in number, for the President’s regime was creaking dangerously towards its end.”

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 saw Sloppy Joe’s fortunes plummet as the American cruise ships sailed elsewhere, and the famous bar closed in 1965. For decades it remained shuttered up, slowly crumbling like much of Havana’s beautiful architecture. One American newspaper described the bar in 1981 as “an abandoned bar-room in a ghost town….the long bar with its single-piece, mahogany top is still there and so are the photos of Humphrey Bogart, Ava Gardner and Frank Sinatra.” Fortunately Sloppy Joe’s was rescued and renovated in 2013. The film version, directed and produced by Carol Reed nine years after he collaborated with Graham Greene on The Third Man, was shot on location in Havana, and today its possible to sit at the same bar as Alec Guinness did and discover not much has changed in the past sixty years.

When Hemingway, Charles H. Baker and Graham Greene were sipping their way though Havana’s nightlife, their rum was invariably made by Bacardi. Don Facundo Bacardi had started distilling rum in Santiago de Cuba back in 1862.

The rafter of his first distillery building was home to a family of fruit bats, from which he designed the distinctive Bacardi logo. Incredibly, Bacardi is still family owned and today is the largest privately-held spirits company in the world. But finding Bacardi in Cuba these days is near impossible: the Revolution saw the Bacardi family leave Cuba for good, building a beautiful art deco distillery in Puerto Rico, rightly described as the ‘cathedral of rum’ These days, most of the rum enjoyed in Cuba is made by nationalised but still excellent Havana Club.

Our three pitstops in Havana are probably the beautiful city’s three most famous, and are prone to tourists wandering in. After sampling their historic charms, you would do well to seek out such delights as the cramped La Dichosa on Calle Obispo, the seedier Bar Dos Hermanos on the waterfront, the elegant late night dancing to be found at Café Paris, or the 1940s styling of Prado No.12. Wherever you end up, and whether it be with a Cuba libre, mojito or traditional daiquiri in hand (we recommend the latter), you’ll no doubt end up with the same conclusion Jack Cuddy and his merry band of American ex-pat journalists did back in 1937, that if Cuba had a national sport, it is still drinking.