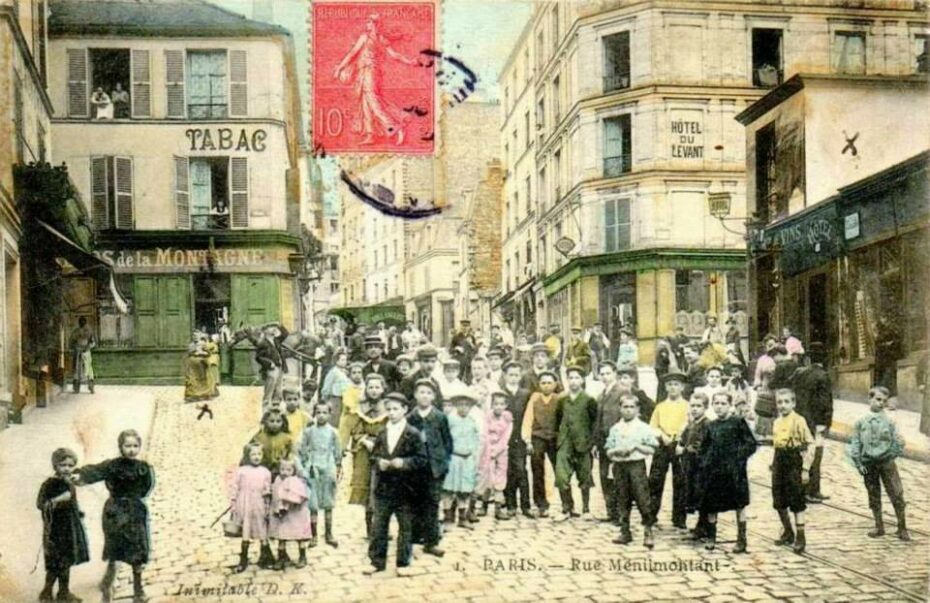

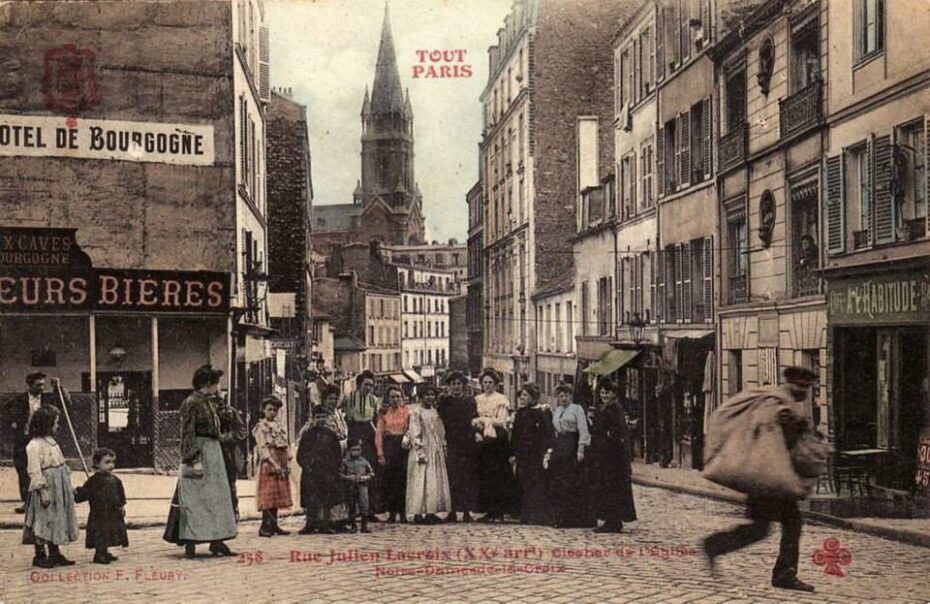

Remember that beautiful Parisian village featured in the Oscar-winning 1950s short film The Red Balloon? Well we’re sorry to report that it was almost entirely levelled by the French government. The history of Belleville, the Parisian neighbourhood where legendary French singer Edith Piaf lived and called home, is a dazzling mix of folklore and fact, like all the best places to visit. There will always be an air of rebellion up in Belleville, the wine-making village built on a hill that turned into a hotbed of working-class radicalism during the Paris Commune of 1871, when almost half the neighbourhood’s population was wiped out in a bloody rebellion against the French government. Belleville is still home to the headquarters of the French Communist Party, and until only very recently, if you were to spend time in the neighbourhood, you would have detected a different Parisian accent, even a deviating dialect, spoken only by the locals. Karl Marx himself was inspired by the revolutionary Parisian workers who fought against a ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, and it’s been said that the Paris Commune acted like a blueprint for communism. At the top of the hill, in between historic artists’ ateliers, we can still find the tell-tale signs of this rebellious country village, where traditional folk songs were the soundtrack to the people’s struggle, and where, according to legend, the quartier’s most famous resident, Edith Piaf, was born on the doorstep of the house at 72 Rue de Belleville in 1913. Just down the street is Aux Follies, a bistro where the French icon sang in her younger days. Today it’s the quartier’s cardinal dive bistrot, where no one will pass judgement for ordering a glass of wine before midday.

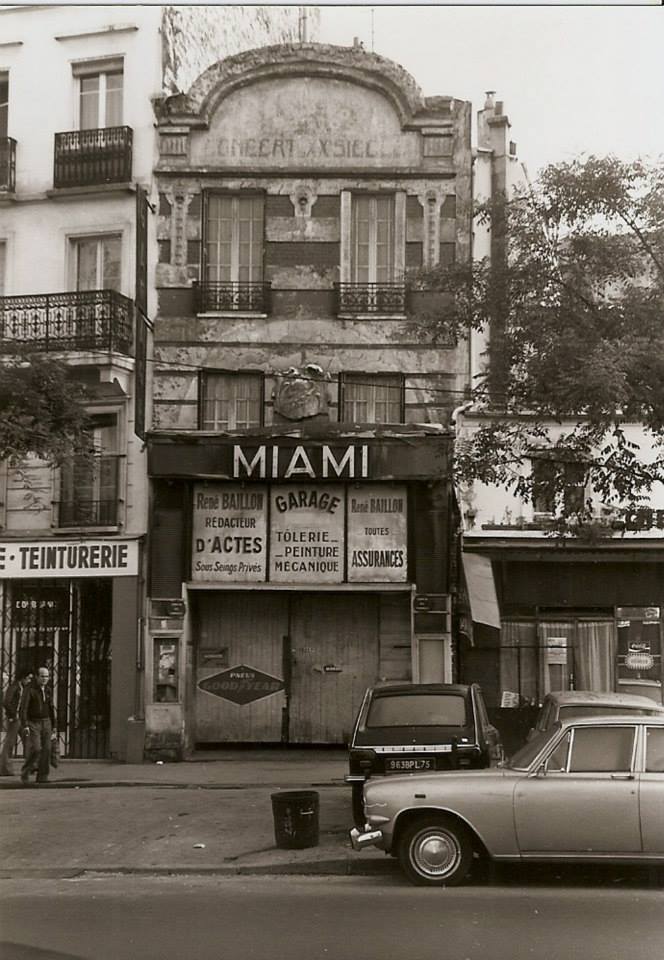

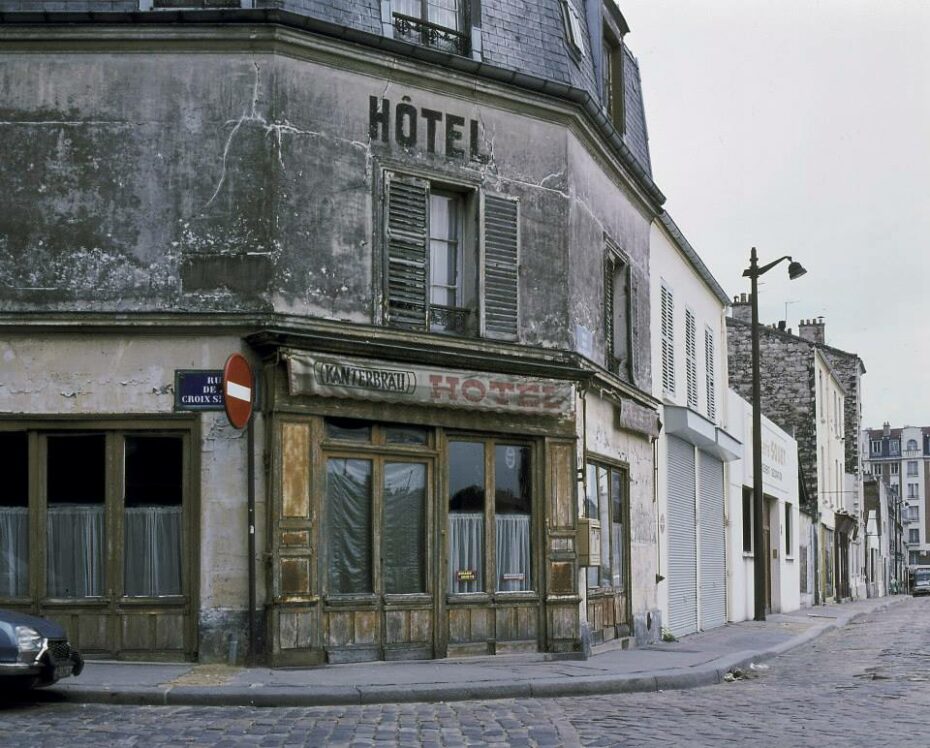

under a streetlight on the corner of rue de Belleville. The working class village gave a new meaning to the saying “if walls could talk.” That was until the 1960s when they came in with a wrecking ball.

In the beginning…

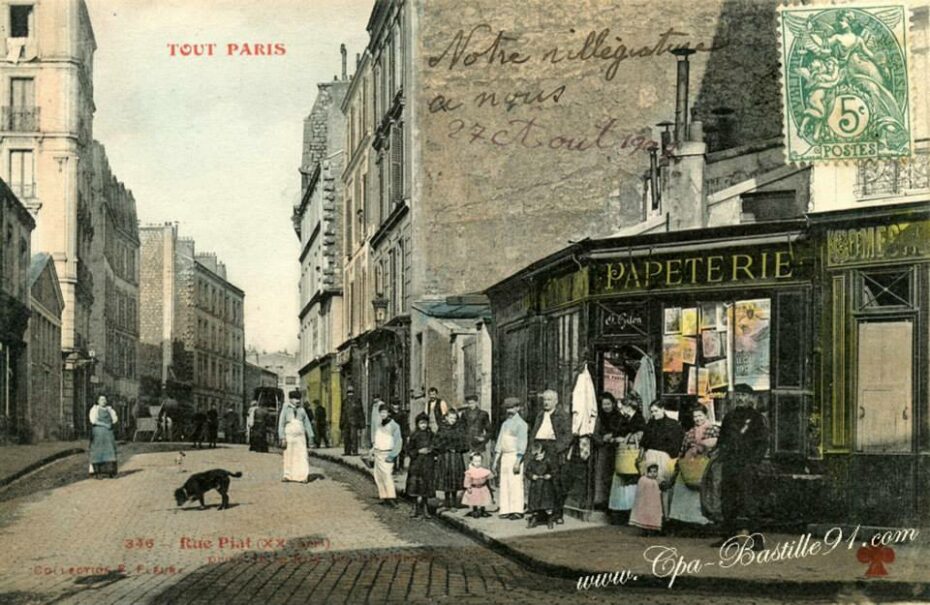

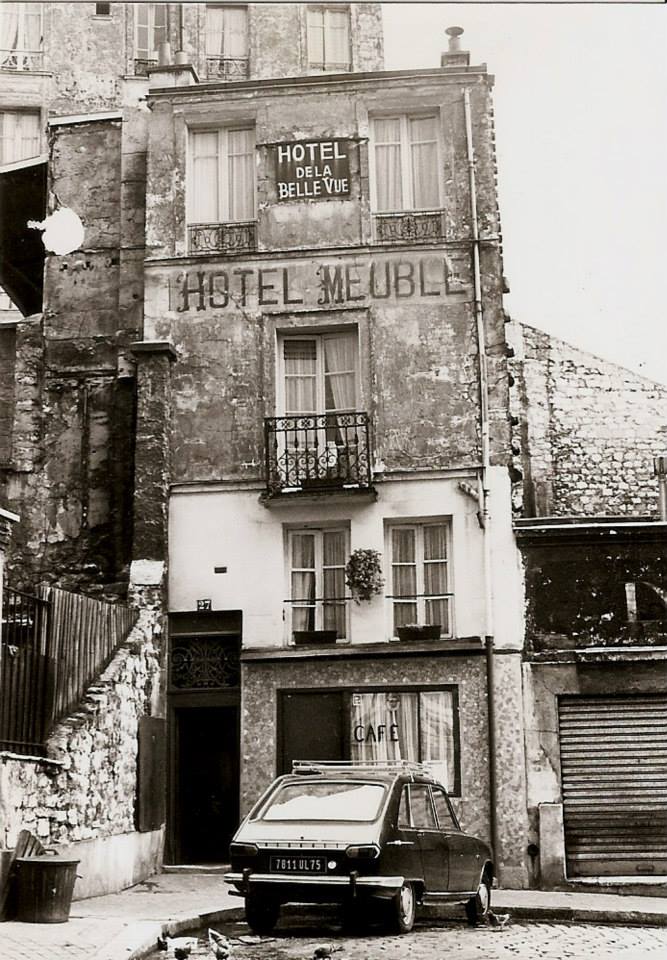

At the start of the 19th century, Belleville was a small village of 2,500 people outside Paris’ walls. Yet, many visitors flocked to its country cabarets flowing with cheap wine. The population swelled as Haussmann’s plans for Paris’ center renovation advanced. Many displaced workers moved to the little village, accelerating its growth.

By the time, Belleville integrated into Paris in 1860, it was home to 60,000 people. What was once the capital of the Canton Pantin, became a smaller 20th arrondissement of Paris’ landscape, and they worked hard for the man.

Change is coming

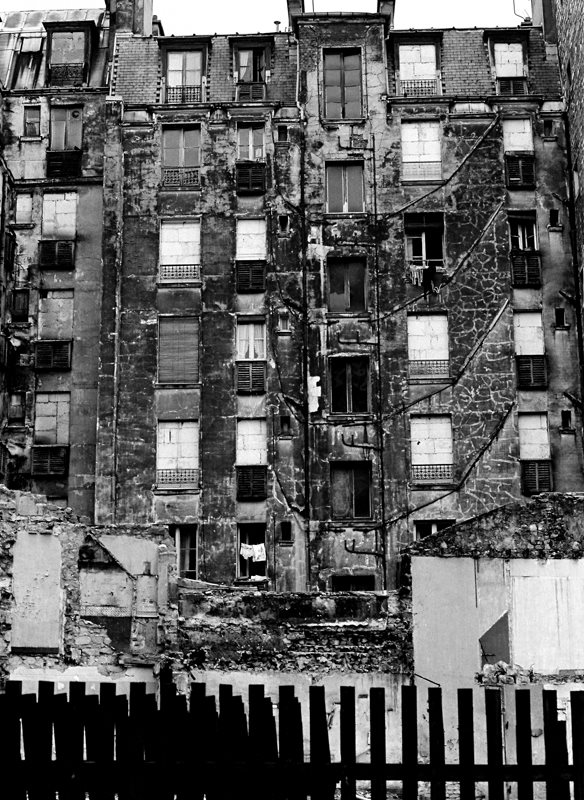

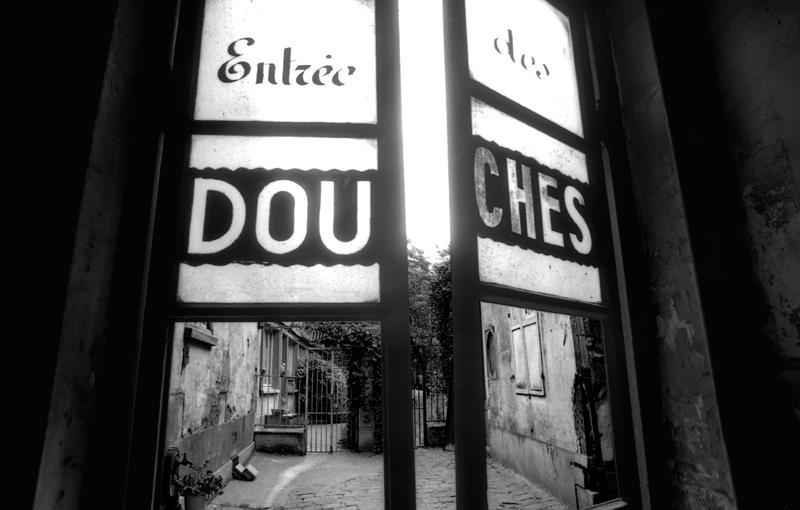

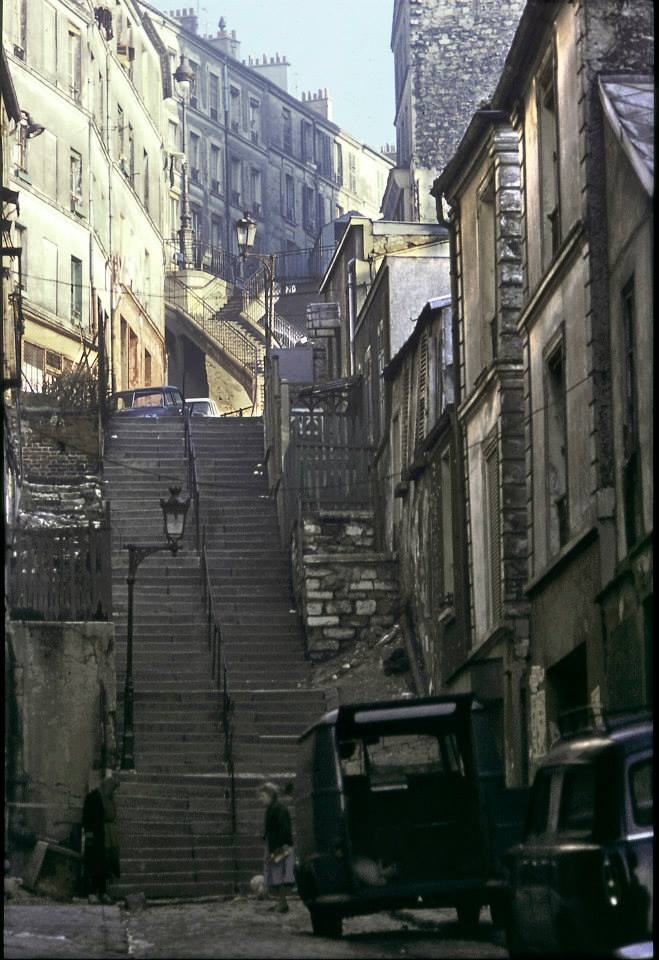

In 1909, Belleville landed on the list of îlots insaloubres or “unsanitary islands”. Its shoddy 19th-century construction of houses on slopes atop unsafe fragile quarry ground and narrow pathways were quite frankly terrible, and sanitary conditions raised concerns about tuberculosis breakouts.

The plan was to destroy and rebuild all these places, but change happened slowly, like with most government projects. Other unsanitary islands on the list were going through the destruction and reconstruction process first. When World War I erupted, priorities shifted.

As the birth of a new middle class dawned, working class Armenians, Greeks, Algerians, Tunisians, Africans who had come to Paris in several waves of immigration were left to live amongst the rubble of sporadic renovation; abandoned in limbo with the expectation of uncertain change.

Then, World War II left Paris in a desolate state. Industries were ruined, food was rationed, and housing was in short supply. Post-war Paris was in dire need of modernisation. So, in the 40s, urbanisation and progress started making their way through Paris. New buildings, metro systems, and skyscrapers emerged. It was the biggest construction project since the Belle-Epoque, a symbolised breakup with the evils of the past, heralding a new age of modernity.

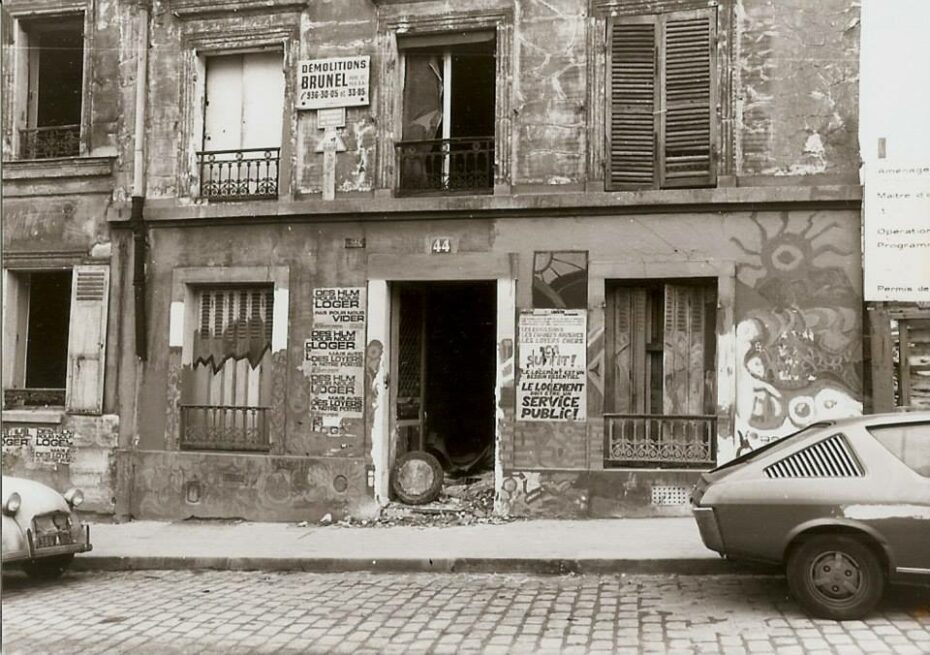

Work on the îlots insaloubres eventually picked up again in the 1970s, and finally it was Belleville’s turn. Old cottages and workshops would give way to modern buildings up to sanitary codes. The pathways taken by donkeys would become modern, wide straight streets.

New Belleville

But all that progress needed investors infusing money into a decaying Belleville. The investors came at a high cost: land developers. The developers started to buy land and move forward with the plans for the new city. First to go was the train station in the Courounnes sector. In its place rose a new 13-story building foreshadowing what was to come to the rest of the areas.

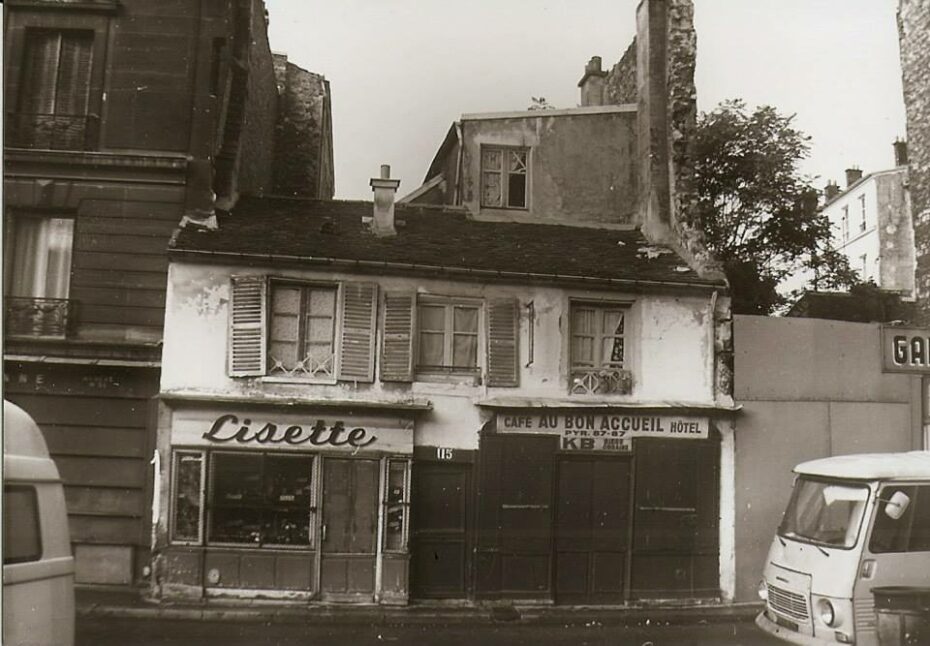

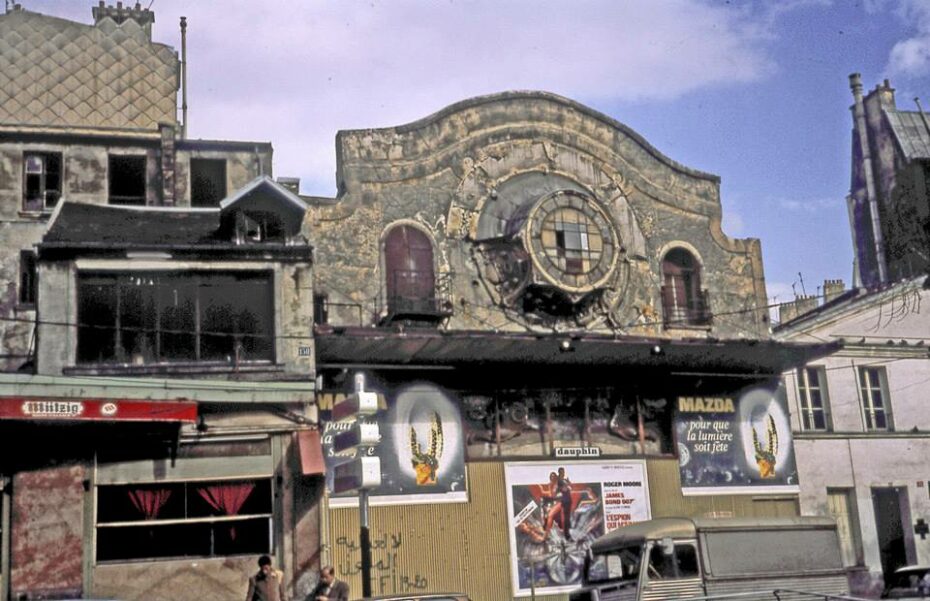

Throughout those years, the population dwindled. Many workshops and shops closed due to the strain of living on a constant construction site. The renewal swallowed most empty spaces and changed them for modern construction. All the newer buildings with bigger living spaces brought new people with more resources.

The ateliers, cinemas, bistros, and studios reflecting the town’s diversity and history were exchanged for purposeful buildings devoid of personality. Photographers such as Serge Degoud, Michel Guillard and Jean-Louis Penel, whose images you are looking at, captured the old districts of Belleville and Ménilmontant; where they grew up, where their families lives; before the destruction of the 1970s. The Oscar winning short film, The Red Balloon (1965) which follows the adventures of a young boy who one day finds a sentient, mute, red balloon, was filmed entirely in the Ménilmontant neighborhood of Paris and offers a rare cinematic glimpse of the quartier. It is available to watch in full on Youtube:

These new suburban areas live in contrast with the other parts of the city that remain untouched. A blend of old and new that reminds everyone of the city’s deep historical roots and importance. In the 90s, residents created the Association La Bellevilleuse to protect and preserve what was left.

Nevertheless, this village’s spirit could never be erased. Places like the brasserie La Veilleuse still have shattered glass bearing the markings of a german shell that hit it in 1918. Still today, the city center is a melting pot of modern and historical buildings, echoing the spirit of self-expression and freedom throughout Belleville’s history.