The nefarious world of conning has long been considered a boy’s club. Even when you google “biggest con artists in the world,” men’s names overwhelmingly dominate the search. Historically, women were thought to have lacked the social capital needed to shrug off the moral trappings of propriety. For the con woman, however, their social limitations are merely another angle to work the hustle. Hiding throughout history, let’s dive into the archives and find our favourite candidates for the real-life Carmen Sandiego…

Jeanne de Saint Remy was one such woman. Although Jeanne was a descendant of royalty, her connection with the royal family was distant to say the least. Jeanne was the illegitimate great granddaughter of King Henry II. Her father, Jacques, was a drunk and the family was impoverished. Once she was of age, Jeanne married a man who called himself Comte de La Motte, giving her the fabricated title of Comtesse (one of many fake titles and names that Jeanne would use throughout her life.) After her husband proved to be as shiftless as her father, Jeanne took on two lovers: famous gigolo Rétaux de Villette, who just so happened to be gifted in the art of forgery, and Cardinal de Rohan, who was obsessed with winning the approval of one Marie Antoinette after being socially rebuffed by the Queen. Jeanne used the opportunity as her way into the royal family and devised a scheme to swindle the most expensive necklace in history.

The exquisite piece was made in the hopes that the previous king’s mistress: Madame Du Barry would purchase it, but she died before being presented the chance. The piece was now bankrupting the jewellers as it was too heavy, gaudy, and expensive for the average consumer. They tried (repeatedly and unsuccessfully) to convince Marie Antoinette to buy the piece.

Jeanne employed her lover, Villette, to forge letters of friendship between herself and the Queen in order to convince Rohan to buy the piece. In them, Jeanne was sure to include the Queen’s secret desire to have the necklace and her fear of the financial burden of buying it. Jeanne painted herself and the queen to be the best of friends in their correspondences. Finally, she presented the forged letters to Rohan, persuading him to buy the necklace and of her ‘real friendship’ with the Queen. Rohan wasn’t totally convinced, however, and asked Jeanne to arrange a meeting between himself and the Queen. Ever-resourceful, Jeanne paid a prostitute who possessed a striking resemblance to Marie Antoinette to fool Rohan. Her impersonation was convincing enough that he purchased the necklace and entrusted it to Jeanne to pass along to the Queen.

With the necklace now in her possession; Jeanne, her husband and Villette the forging gigolo, got to work selling off the diamonds, amassing a fortune. Jeanne’s loose-lipped husband was soon caught and arrested however, and ultimately, so were Jeanne and Villette.

The King and Queen insisted on a public trial to defend their honour, but it wouldn’t quite pan out how they expected. Instead of convincing the public of the Queen’s innocence in the matter, the public perception of her soured even more. So much so, that it’s said that this incident was the tipping point for the French Revolution.

Jeanne played the part of martyr beautifully, garnering so much public sympathy that the press wrote that she was the true victim in her own con.

Even with the sympathy of the people, Jeanne was the only one of her posse to be sentenced to prison. She escaped soon after, disguised as a boy and fled to London where she published her memoir: Memoirs of the Comtesse de Valois de La Motte. This memoir detailed much of her early life and the entire scandalous con and has spawned several films and television adaptations, including one starring Academy award winner Hilary Swank. But a woman like Jeanne could not merely die in obscurity or go on to lead a normal life of course. In 1791, at age 35, Jeanne fell out of her hotel window to her death, apparently escaping debt collectors.

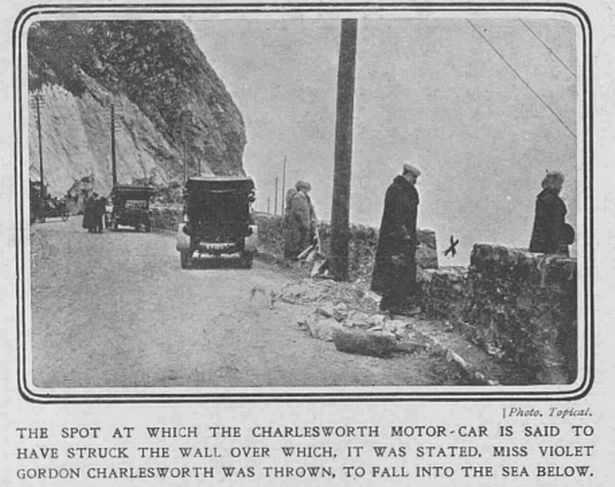

Violet Charlesworth

Rivaling Jeanne’s bombastic story is a hard task, but Violet Charlesworth comes pretty close.

Born the youngest of four children in 1884, Violet got her start in the con game early. Although her father made decent money as an insurance agent, apparently the Charlesworth family thought they deserved more. Together, Violet and her mother Miriam, devised a lie to centre Violet in the wealthy dating pool.

They claimed that Violet was actually the goddaughter of General Charles Gordon, a famous British Army officer who had been killed in action. The lie convinced wealthy suitors that Violet was a lucrative heiress, and soon the money began pouring in from rich suitors. Violet poured this money into stocks, a fleet of automobiles, jewels, and a diamond tiara. Her wealth, beauty, and social grace made her a true socialite in the eyes of the press – and they documented Violet’s every move. With creditors on her tail, by her 25th birthday, Violet knew it was time to get out of the con game before it was too late. On a January night in 1909, she faked her own death by sending her car off a cliff, and beat a hasty retreat to a hotel in Scotland. The sensational story made headlines worldwide. The hunt for the body of the missing heiress was on. False sightings began popping up in papers until, finally, Violet was found hiding out in the Scotland hotel.

For her crimes, Violet was sentenced to two years of hard labor in Aylesbury in England and was released in 1912 back to Scotland. Not much is known about Violet’s life after her release, but her sensational ploy lives on as the cliff side she staged her death on would forever be known as ‘Violet’s Leap.’

Bertha Heyman

Bertha “Big Bertha” Heyman, was dubbed ‘The Confidence Queen’ for her conning abilities. Some reports marvelled at her ability to swindle as many men as she did due to her “stout, gross-looking” appearance. Other accounts claimed that she was, in fact, an attractive, plus sized woman with an arresting gaze. Regardless of Bertha’s level of attractiveness, she was still able to swindle thousands of dollars out of numerous men while living in the lap of luxury.

Bertha employed the age old tactic of ‘fake it till you make it.’ She pretended to be a wealthy woman unable to access her fortune and in need of financial assistance until she was able to access her funds again. To do this, Bertha positioned herself amongst wealth by staying at luxury hotels and bragging to any parlour room that would listen about her connections to rich and powerful people. By 1880 it was an open secret that Bertha was a notorious scammer. The Chicago Tribune reported: ‘She has long since earned the sobriquet in the police circles and other cities as ‘The Confidence Queen.’ After fleecing thousands more out of several individuals, Bertha was finally arrested by the notorious Pinkerton Detectives. While serving her time, she was able to get in touch with a man by the name of Charles Karpe, who gave Bertha $1,000 after she convinced him that she was the owner of a strong box that contained jewels and bonds. She promised to pay him back twice over after she bribed her way out of jail with the money. Karpe would go on to loan Bertha thousands several times over until he had nothing left to give.

Even after scamming people under the noses of the guards, Bertha was released from Blackwell Prison. She went to live at the historical Hoffman House in New York City where she continued to swindle folks before being sentenced again to five years in Sing Sing Prison. It was reported that she conned over $87,000 from her victims.

While imprisoned for a third time in San Francisco, Bertha talked openly with the press, attracting the attention of theatre impresario, Ned Foster. Enraptured by Bertha’s reputation, Foster saw in Bertha the perfect opportunity to capitalise on her appeal. He bailed her out and began putting together a stage show centered around her. Foster promoted Bertha by organising photo shoots for cabinet cards and selling them at ¢.25 a pop. Posters were plastered around the city promoting Bertha’s stage act and the press reported on her upcoming debut. When it was time for the show, Bertha did not disappoint. She scandalised audiences by wearing flesh coloured tights and participating in staged boxing matches where she knocked out her opponents.

Bertha spoke rather proudly about her extensive career in the con game saying: “I take no pride in overveiling a fool. The moment I discover a man’s a fool, I let him drop. But I delight in getting into the confidence and pockets of men who think they can’t be ‘skinned.’ It ministers to my intellectual pride.”

May Dugas

May Dugas began her con career around the same time Bertha was starting her legitimate one. In 1887, after relocating to Menominee Michigan, May found work as a prostitute in one of the top bordellos in Chicago, Carrie Watsons, where she got the idea to begin blackmailing her married, wealthy clients. May would put herself through university; taking classes on psychology, French, and business law. This was in part because she was genuinely intelligent, but also to make herself more appealing to her wealthy and intelligent clientele. May tried to marry her way into wealth when she attracted the eye of a rich young man, whose father, immediately suspicious of May, hired Pinkerton Detective, Joe Edwards to investigate her.

Edwards entrapped May by setting her up in illegal dealings, which was all the evidence her beaux’s father needed to bribe May to leave town. May conceded, but not before securing a $20,000 bribe for her to go quietly. In San Francisco, May was arrested for attempting to rob a wealthy suitor, but she seduced the prison guard and, after spending only one night in prison, escaped to an ocean liner headed for China. Thus began May Dugas’ globe trotting adventures.

May’s Shanghai excursion began with her taking up with a rich British mining executive whom she blackmailed out of $25,000. She continued her journey east and landed in Tokyo where she met and fell in love with an American expat who lavished her with money and jewels. Her old friends at the Pinkerton Detective Agency had not forgotten about her, however. With even more crimes under her belt, they tracked May to Tokyo, forcing her to skip town again. It was said that this left her suitor so distraught that he committed suicide several months later, but (as if May’s story wasn’t sensational enough), the coroner concluded that he had actually been murdered.

This time, May set sail for London where she landed her biggest fish yet, Baron Rudolph van Eerde. By 1892 the couple was married at his Netherlands estate. At just twenty-three year old, May Dugas was now Baroness May Dugas de Pallandt van Eerde. Bred for a life in upper crust society, May lavished in the royal social circles she now found herself in. So much so that she never seemed to find time for her husband. After years of dissatisfaction with May’s avoidance of him, the Baron asked for a divorce. When May refused, the couple agreed to sign a deed of separation in 1899, which provided May annual support. Upon his death, May inherited her husband’s fortune along with her Baroness sister-in-law’s fortune.

May returned back to Menominee as the greatest success story. She bought her mother a grand, eccentric house rumoured to be filled with rare artefacts and secret passageways. She bought her brother a resort hotel in Arkansas. When a wealthy socialite, Miss Frank Gray Shaver, arrived in town fresh out of law school and having inherited $375,000 from her father, May took immediate interest in her. She invited Shaver on a world tour, much to her delight. The socialite was so taken with her new friend that she was almost willingly conned out of much of her inheritance.

Eventually, Miss Shaver realized that she was being had. Distraught and hurt, she took May to court and the scandalous story drew audiences that packed the courtroom. Shaver’s lawyers pointed to May’s past history with wealthy men as well as her former career as an escort. May responded to the allegations by fainting and halting court. After this incident May tried to take an oath of poverty, but was still made to pay $13,515 to Shaver who was awarded a $70,000 judgement.

After the trial, the Baroness entered a relationship with Lord Powerscourt Allen, a member of a prominent Irish family, and she returned to Europe where she was welcomed by royal society. May seemed to live the latter half of her life in relative obscurity. She died seeking treatment for cancer in New York City in 1937.

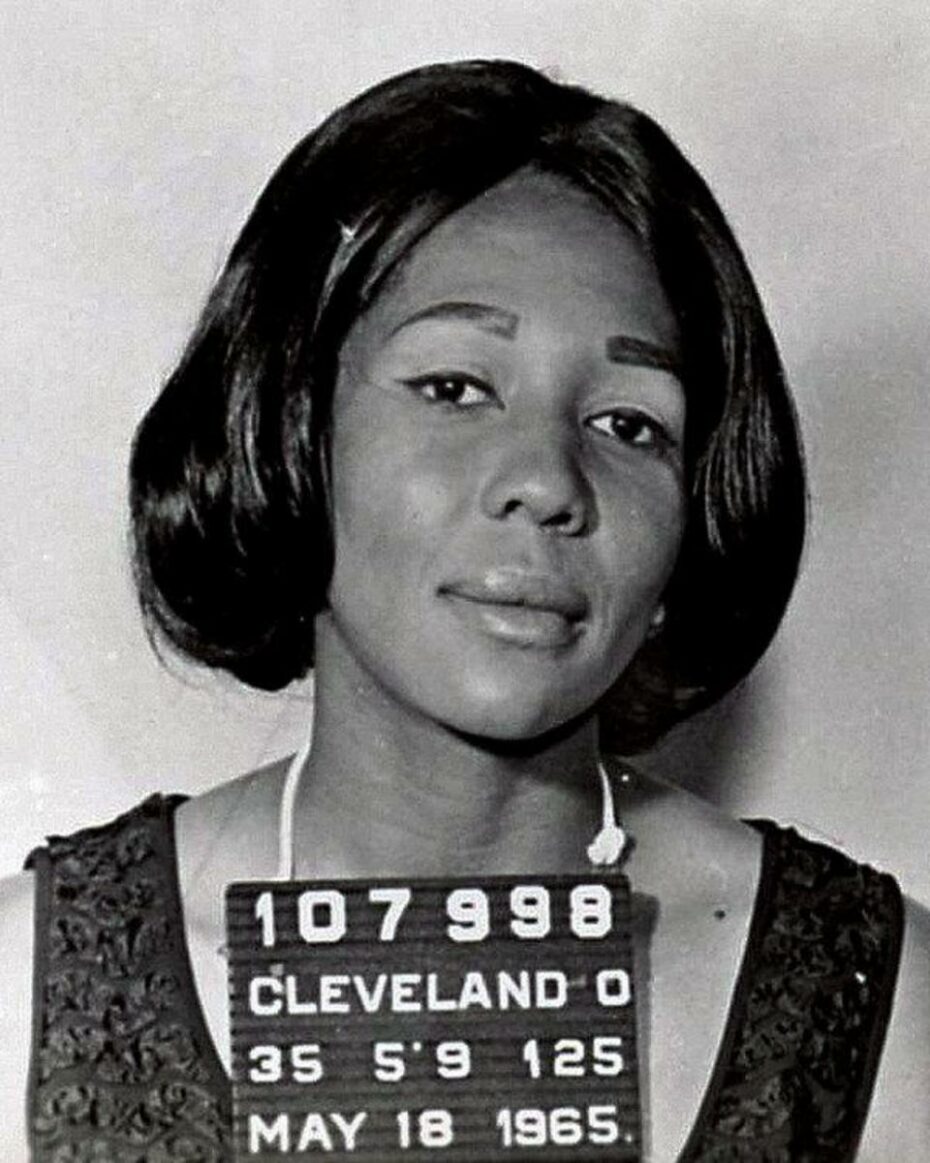

Doris Payne

Our final con woman has earned her name in infamy as being the greatest jewel thief to ever live, and — up until recently — she was still pulling jobs. Doris Payne fell into the life of crime accidentally when one day she went to a drugstore to run errands for her mother. The store clerk, who at first had been friendly to Doris, quickly changed his tune when a white patron entered the store.

Not wanting to be caught treating Doris favourably, the clerk kicked her out. Confused and upset by this, Doris realized on her way home that the store owner forgot to take back a watch he had let Doris try on in his haste to get rid of her.

She considered, for a moment, going back to return the watch, but thought better of it. Not only was this payback for mistreating her, the money could go to someone who needed it much more than the store clerk. Payne pawned the watch and saved the money with the hopes of getting her mother out of her abusive relationship with Doris’ father.

Thus began Doris’ life of crime. Once she became of age, Doris escaped her hometown and moved to Cleveland Ohio where she became a nurse. She began toying with the idea of stealing again and began crafting her game by absorbing fashion magazines. She elevated her style and emulated the rich white women she observed in movies and magazines; transforming herself into the picture of an upper class Black woman complete with high end clothing and jewels. She called this persona “Miss Lady.”

Her con was complex, but brilliant. Doris would ask for several pieces of jewellery to be brought out all at once and then, by sleight of hand, would begin moving the pieces around so quickly, trying on and removing them, so that the jeweller could no longer keep up. In the midst of the confusion she would slip a piece in her purse and point out the missing piece to the jeweller, going to great lengths to help them locate the “missing” piece and then suddenly “finding” it. This trick made jewellers believe Doris was trustworthy enough to leave her alone to browse the selections while they tended to other customers. When their defences were down, Doris would slide on a piece and simply walk out. Doris began making a pretty penny by reselling stolen jewels in other cities and states. All the while, she would send the money to her mother.

She would make her first big score in 1953 in a Pittsburgh jewellery store when she managed to make off with a $20,000 diamond. For fear of being followed, she spent the night in the bathroom of a Greyhound bus station. She had no reason to worry, however, because the next day she was able to pawn off the jewel for the equivalent of $65,000.

With this new found confidence and success, Doris bought herself, her family, and her mother new homes. In 1957, she began dating a man by the name of Harold “Babe” Bronfield; a man with deep ties to the criminal underworld and even deeper pockets. In fact, it was Harold’s impeccable legal team that allowed Doris to wiggle her way out of serving jail time when she was caught stealing in Pittsburgh. However, the sensationalism of a Black female jewel thief escaping legal recourse, meant Doris’ identity had been compromised in local papers and media. This forced Doris to move to a smaller city where she may not be recognised, but smaller cities meant smaller scores. Not only were the pastures no longer as green for Doris, sometime after her move, her well connected beaux died, leaving Doris without the money and protection she had become accustomed to.

It was time for a new approach. It was time to take her con game international. In 1974, Doris would relocate to Monte Carlo in France, where she pulled her biggest heist yet. She would steal a diamond ring from Cartier valued at over nine figures. Intending to skip town before anyone could ever suspect what she’d done, Doris headed for the airport immediately. But the police were already a step ahead. In custody, Doris managed to pry the diamond from the ring’s setting and disposed of the band. She managed to hide the diamond itself in her girdle. After conducting several full body strip searches, the police were stumped when they were unable to find the ring, but without any evidence, they couldn’t hold Doris. They released Doris with her clothes. The diamond was still hidden in her girdle. Doris fled to New York City to sell the ring for $150,000.

Her next big heist would be at Bulgari in Rome where she managed to make off with a diamond worth hundreds of thousands. Several passports, identities, jewels, and decades later, Doris was finally pinched in 1999. She was sentenced to twelve years after stealing a $50,000 ring in Denver, but only served five.

The new millennia did not slow Doris down and between 2010 and 2013 she continued to steal high end clothes and jewels. In October 2013, Doris was detained for stealing a $20,000 diamond ring in Palm Desert California.

By this time age had begun to catch up with Doris. Not only was she not as fast as she used to be, but technology had greatly improved and she was now being caught on security cameras. She also stole more out of compulsion than necessity by this point. It had been all she’d known up until this point.

Recently her lawyers have plead on her behalf by citing her age and health. Still, after decades of major and minor heists all over the world under various identities, Doris has rightfully earned her spot as the world’s most infamous international jewel thief.