Ever since humanity invented cake, we’ve been trying to have it and eat it, too. And while we haven’t yet figured out how to do both, we have been saving slices of this most celebratory of desserts for several millenia now.

The Egyptians gave us the world’s oldest known cake–and also the world’s oldest Tupperware as it happens. During the reign of Pepi II from BCE 2251 to 2157, bakers mixed up a wheat dough for flatbread and filled it with honey and milk. The dough was poured into two pre-heated copper molds that fit tightly together. The heat from the molds formed air bubbles inside the cake, which escaped as it cooled, creating an air-tight seal inside the copper dome. To the ancient Egyptians, bread symbolized renewed life, and this preserved cake accompanied Pepi’Onkh, a member of the royal family, as he made his journey to the afterlife. The cake was discovered in Pepi’Onkh’s tomb in 1913 and is held today by the Alimentarium Museum in Vevey, Switzerland.

Modern-day China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region served for centuries as a key connection between East and West. Situated along the Silk Road, Xinjiang represents a historical convergence of cultures, from nomadic Tibetan Buddhists to Turkic Muslim farmers. This delicate, palm-sized cake embodies the influences of trade and migration across the centuries. While the golden crust looks almost as if it just came out of the oven, the cake was baked nearly 1,400 years ago and placed in a tomb in the Astana Cemetery, a collection of more than 1,000 burial sites built during the Tang dynasty near the now-abandoned oasis city of Gaochang. The region’s arid climate helped preserve the cake, which bears a striking resemblance to mooncakes still eaten today, including the elaborately molded baoxiang hua or treasure-chest flower design. While baoxiang hua is a common Buddhist motif, the cake’s filling is likely made of dates, walnuts and raisins, products that would have made long journeys over ancient trade routes to end up as nourishment in the afterlife for a wealthy Gaochang resident.

Londoners knew how to throw a great party during the Little Ice Age. They also knew that no party is complete until there’s cake, which is why gingerbread featured prominently among the festivities of the Frost Fairs. Between the 1600s and 1800s, the Thames froze over completely on a fairly regular basis. Enterprising ferrymen and merchants sensed a business opportunity and set up tents directly on the ice to sell wares and novel experiences to their fellow ice-bound city dwellers. While games and souvenir stalls brought much merriment, the main attractions were food and beverages, with gin flowing liberally from makeshift taverns and thick slices of gingerbread served alongside the stiff drinks. Though the fair of 1814 would be London’s last, we can still get a small taste – metaphorically, at least – of the frosty food scene thanks to a perfectly preserved piece of gingerbread from the final Frost Fair. The 200-year-old cake is hard as a brick now, but according to the Museum of London it still gives off the warming scent of cinnamon, ginger and cloves.

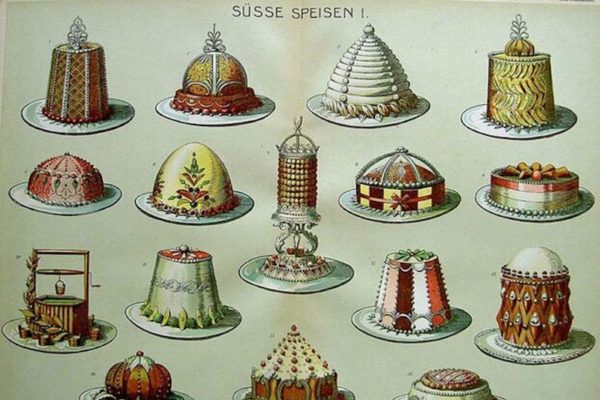

When Queen Victoria married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in February 1840, she changed the wedding industry forever and set trends to which brides still adhere today, including making the white wedding gown de rigueur. And while cakes baked to celebrate nuptials were already an established tradition dating back to the Romans, Victoria’s wedding cake created a new standard for reception confections. Weighing in at 300 pounds, the three-tiered English plum cake measured 10 feet across. Mirroring the Queen’s wedding dress, the cake was draped in white royal icing–an incredible luxury at the time due to the high price of refined white sugar. A miniature statue of Britannia, the personification of Great Britain, stood atop the cake, blessing tiny versions of Victoria and Albert clad in Roman attire. (It isn’t difficult to see where today’s white frosted cakes topped with miniature brides and grooms got their royal inspiration.)

Small slices of the massive cake were boxed up, sealed with the royal cypher and distributed to guests and people who were involved in preparations for the wedding. It’s common today for newlyweds to save the top tier of their cake for their first anniversary (in the U.S.) or the christening of their first child (in the UK), but not many couples save them for more than 150 years. Yet in 2016, a slice of Victoria’s wedding cake surfaced for auction at Christie’s, fetching GBP 1,500.

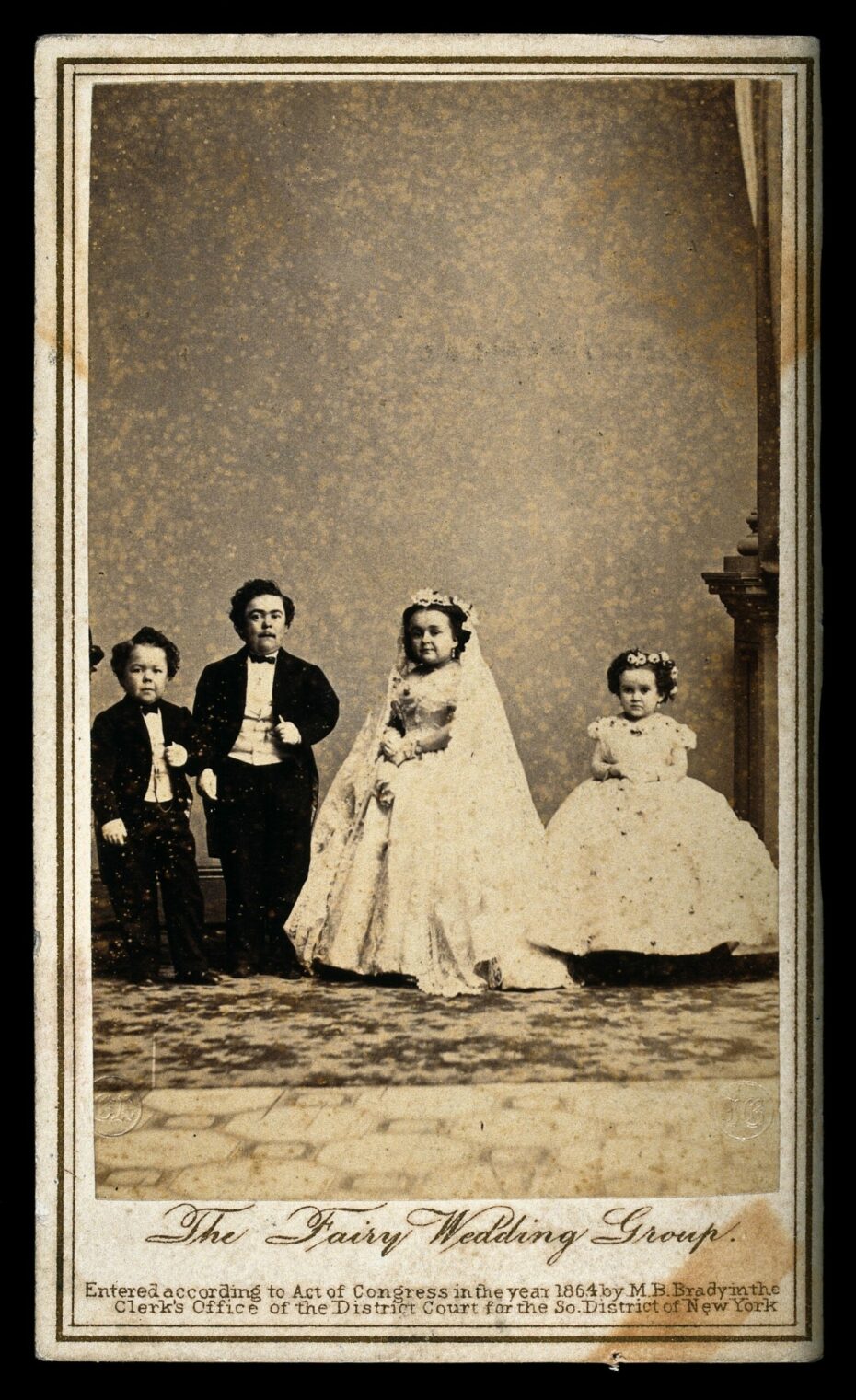

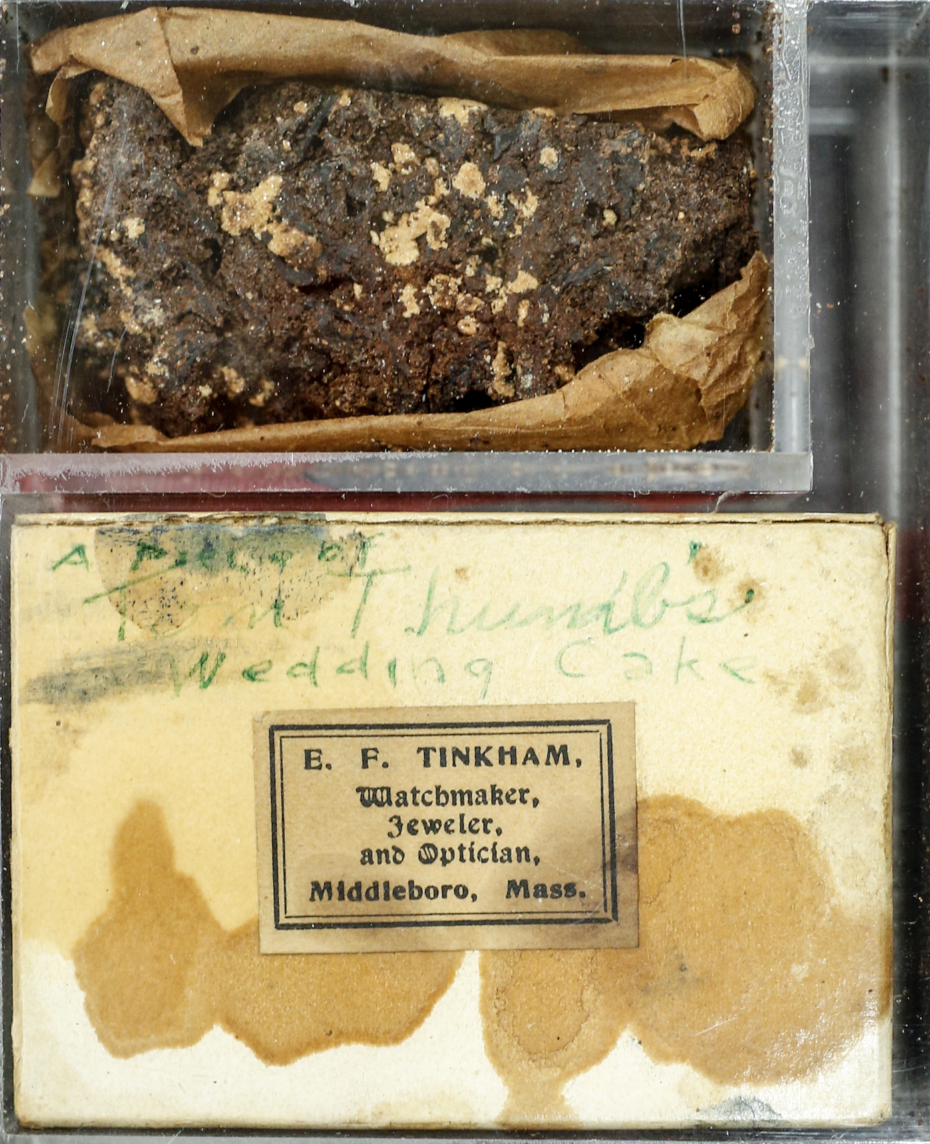

What the U.S. lacks in the royal wedding department it certainly makes up for with spectacle. Spectacle was a full-time occupation for circus and sideshow impresario P.T. Barnum, and in 1863 his foray into the wedding business created a sensation that pushed the Civil War off the front page of the New York Times. Charles Stratton was recruited by Barnum at age 5 to perform in his American Museum. Due to his small stature, a result of dwarfism, Stratton was billed as General Tom Thumb. Renowned as a gifted actor, comedian, dancer and singer, Stratton toured the U.S. and Europe and performed for Queen Victoria twice. When he wed fellow Little Person Lavinia Warren Bump, dubbed the Queen of Beauty, the event was billed as the Fairy Wedding and was by all accounts the society event of the year. The couple was even welcomed to the White House by President and Mrs. Lincoln following the wedding. Their reception was held at the Metropolitan Hotel in New York City and was attended by 10,000 guests–-5,000 of whom bought tickets sold and promoted by Barnum himself.

Boxed slices of the couple’s bridal fruit cake, which was outfitted with four detailed Cupids, were distributed to the ladies in attendance. Several of these slices still exist today, including pieces in the Library of Congress and the Barnum Museum.

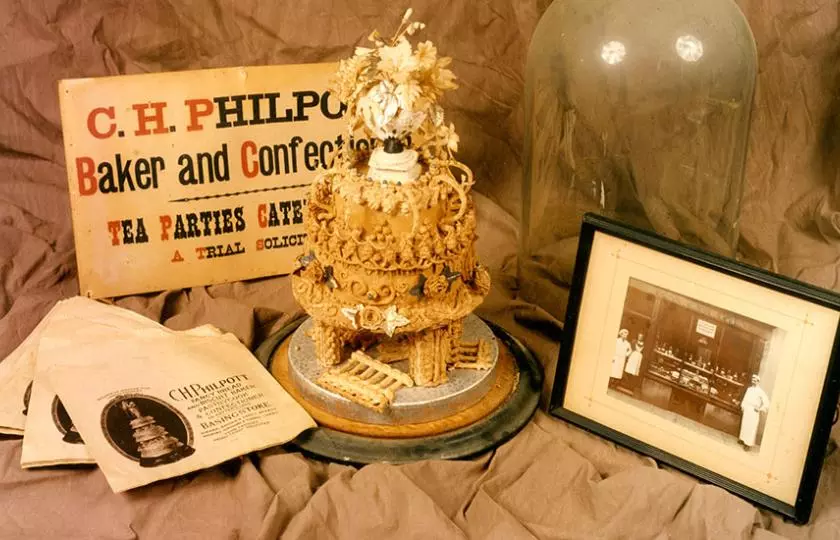

As the price of refined sugar decreased, towering, white-frosted wedding cakes became accessible to the masses as well as royalty. In 1898 Charles Philpott and his wife opened a bakery in Basingstoke, England. In order to advertise their wares, they baked an elaborate wedding cake bedecked with pearly icing columns, frosting buttresses and delicate sugar flowers and placed it in their shop window as an example of their work for passers by. When Basingstoke was heavily bombed during World War II, the cake, still in its bakery window, survived with a single crack. It remained on display at the bakery until the Philpotts retired in 1964, at which point they moved it to their home. In 1995, the Philpotts’ daughter donated the intact cake to the Willis Museum. According to museum preservationists, the cake was still moist inside at the time of donation. But don’t get any ideas about enjoying a slice today. To ensure the cake perseveres for future generations, the museum dried it with silica gel and strengthened the interior with glue.

In 1910, British explorer Robert Falcon Scott led an expedition aboard the Terra Nova in a race to be the first to reach the South Pole. The grueling work of trekking across the frozen landscape of Antarctica requires a high-fat, high-sugar diet to sustain the body, so Scott commissioned bakers Huntley and Palmers to supply cakes and biscuits for the team. Tragically, Scott not only missed being the first to the Pole by 34 days but he and his team froze to death only 11 miles from the next depot with food and supplies. In 2017, the Antarctic Heritage Trust embarked on a project to preserve the first buildings constructed at Cape Adare. Among the artifacts uncovered was a rusted tim from Huntley and Palmers containing a paper-wrapped fruitcake from Scott’s expedition.

While the cake reportedly had a very slight rancid-butter scent, it had been almost perfectly preserved by the extreme cold. Like all of the other 1,500 artifacts collected during the preservation project, the fruitcake tin underwent a few conservation efforts such a rust removal, deacidification of the label and physical repair of the wrapper. The cake itself was left untouched, and the package was returned to the restored hut where it was found.

Late in the night of March 28, 1942, British Royal Air Force planes roared into the airspace over Lübek, Germany, raining bombs over the city in retaliation for the Nazi bombing of Coventry two years earlier. It was the evening before Palm Sunday, and merchant Johann Wärme’s family had set out a hazelnut-almond cake, a fine coffee service and a gramophone with records such as Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata and Ninth Symphony for the next morning’s celebrations. Those celebrations never came, as the house collapsed under heavy Allied bombing.

But during a 2021 excavation, archaeologists found the charred remains of the cake in the home’s basement. While it had shrunk to a third of its original size due to the heat of the shelling, the cake’s frosting swirls were still recognizable.

You may notice that many of the preserved cakes in our brief compendium are fruitcakes. A generous soaking of brandy or other alcohol means fruitcake is far more likely to stick around for generations than the average fluffy, white birthday variety. Today, fruitcake is the butt of many a holiday joke, with some people contending only one fruitcake exists and it is simply passed from person to person each year. But for one Michigan family, that’s no joke. Fidelia Ford had a tradition of baking a fruitcake annually and letting it age for a full year before serving it during the holidays. In 1878 she baked her last cake; she died before the holidays arrived. The family couldn’t bear to slice into the cake after the loss of their matriarch, so the cake was passed down from generation to generation, enclosed in a glass compote dish. The cake’s fate was uncertain for a brief time in 2013 when Morgan Ford, the cake’s caretaker since 1952, died at the age of 92. None of his family members were particularly enthusiastic about taking on the responsibility of a 137-year-old fruitcake. But eventually Ford’s daughter Julie stepped up to the glass compote dish, and the family’s fruitcake tradition lives on.