Some American companies are such a part of our everyday lives, they’re taken for granted, the likes of Apple, Microsoft and Google for example. But there is another company that although it can be seen everywhere, no-one notices. Even more mysteriously, the company no longer exists. But walk through any American city, or picture its greatest manmade landmarks and the chances are it was made with Bethlehem Steel. For over a century, the star of Bethlehem Steel burned bright, becoming one of the world’s largest producers of steel. Based in a small city in Pennsylvania, the company built the backbone of America; from the Chrysler Building to the Empire State Building, the Hoover Dam, Madison Square Garden, Rockefeller Centre, the Golden Gate Bridge, even the prison island of Alcatraz were just some of the iconic structures made with Bethlehem Steel.

By 1940, a staggering 80% of New York’s famous skyline was built with Bethlehem Steel. But by the 1990s, the unthinkable happened, and this titan of American industry went bankrupt. The blast furnaces closed, taking most of the city of Bethlehem’s fortunes with it. One winter’s day we went to visit the haunting ruins of the city that built America.

Bethlehem can be found about two hours north of Philadelphia, and is very much a tale of two cities. Divided by the LeHigh River, in the north end you’ll find beautiful and historic old Bethlehem, one of the oldest communities in America. Settled by German Moravians in the 1700s, it was christened with its iconic name on Christmas Eve 1741, by bishop Count Zinzendorf who while ‘conducting a love feast named the place Bethlehem.’

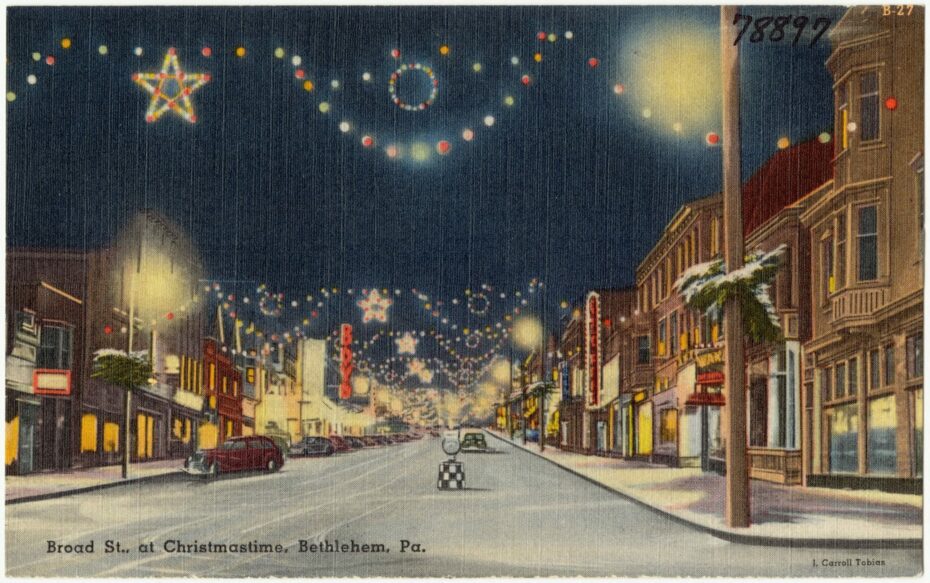

The city became the first in America to feature a large, decorated Christmas tree in its centre, and was officially recognised as ‘Christmas City USA’ in 1937. Still today, the holiday tradition plays a large part in Bethlehem life with authentic German Weicnachtsmarkts, a life-sized Advent calendar, and a giant illuminated star on South Mountain in a nod to its famous namesake in Palestine.

Wander through this beautiful old city and you’ll find one of America’s great historic hotels, the Hotel Bethlehem, as well as the oldest bookstore in America, the Moravian Bookshop which opened in 1745. This quaint city is steeped in old world charm, where every house window is lit by atmospheric candlelight, and you can hear the clatter of horse drawn carriages on cobblestones. Full of enchanting discoveries, curiously, it is perhaps the only place in America where you’ll find the tombstone of a soldier from Napoleon’s Grand Armée, belonging to one Karl Matthew Kafka, inscribed ‘Soldat de L’Empereur Napoleon, 1798-1813’.

Follow the hillside down from the historic Hotel Bethlehem, and you’ll find the remarkable ruins of the industrious Moravian settlers: a creek mill, brass foundry, blacksmith shop, clockmaker, tinsmith, pewterer and a dye house. In short, one of America’s earliest industrial parks. Upon visiting in 1777, John Adams described this “curious and remarkable town where they have carried the mechanical arts to greater perfection than in any place which I have seen.”

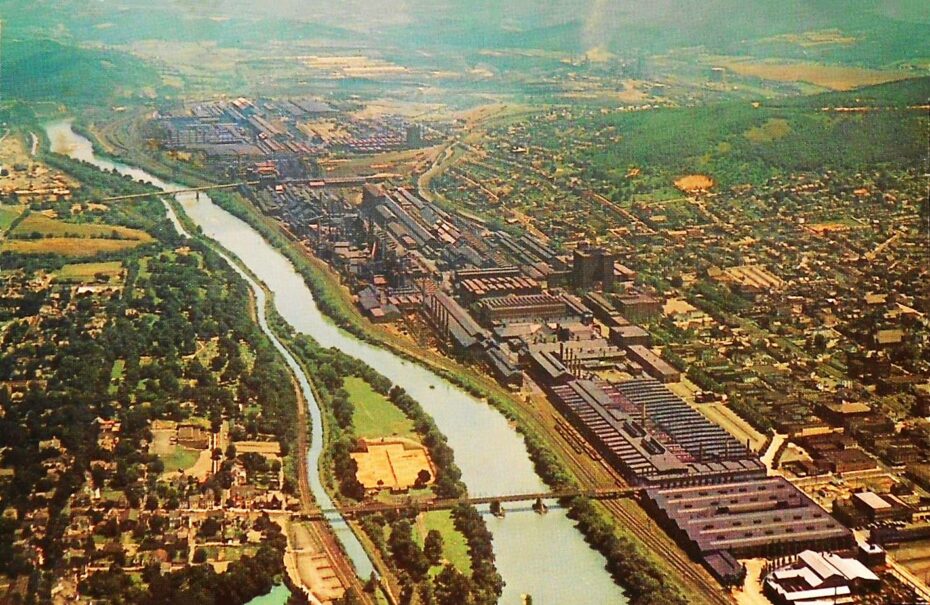

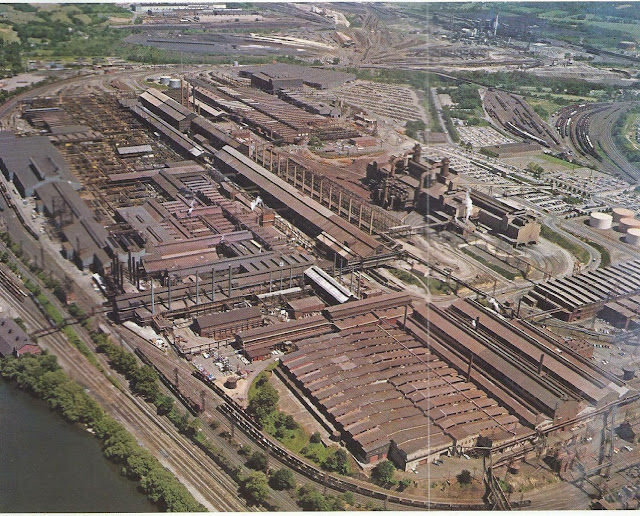

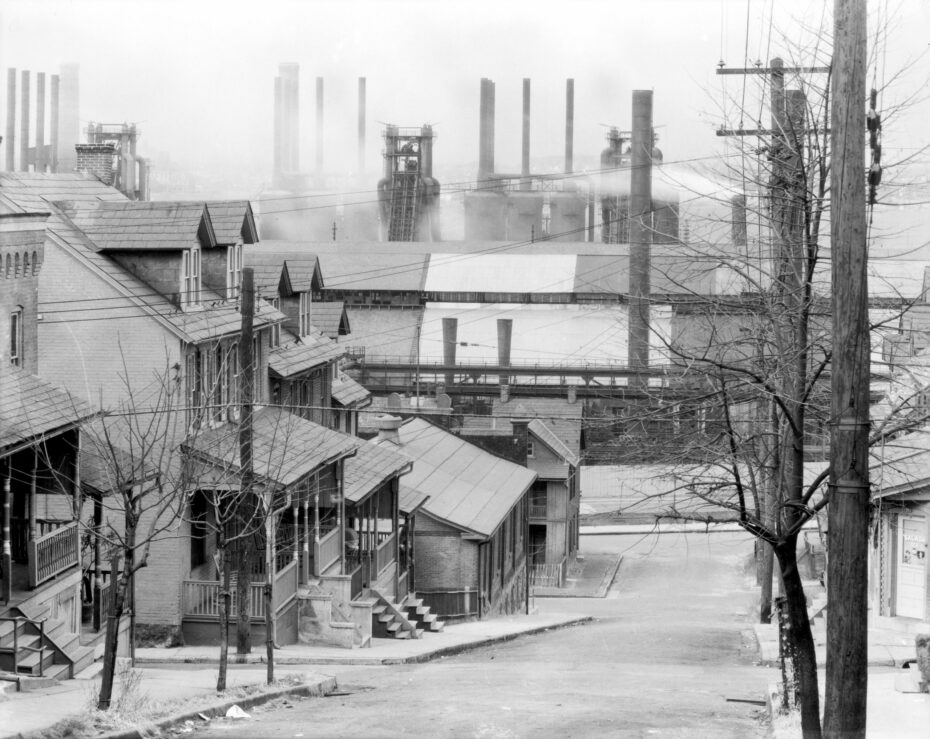

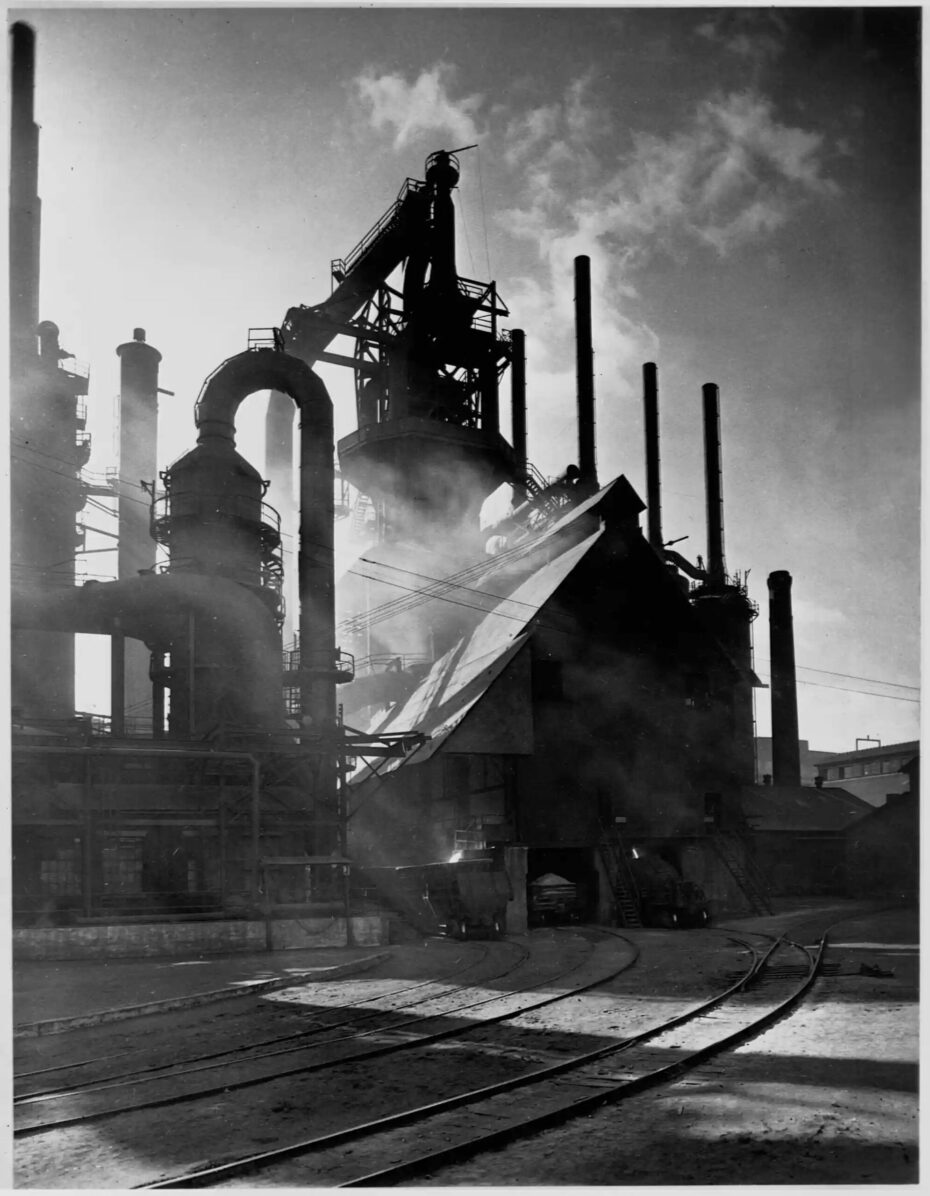

A century later, nowhere in America was this more true than in the southern half of Bethlehem, where you’ll find the vast industrial ruins of the old Bethlehem Steel plant. The steelwork ruins are unmissable: the plant covered nearly five miles and stretched two hundred and thirty feet into the air, a dense tangle of rusting machinery surrounded by crumbling brickwork of a miniature city that was once home to furnaces, open hearths, railways and forges.

To give a some sense of the scale, just one of these brick buildings, the former Number 2 Machine Shop is five football fields long. This colossal monolith to American industrial might was known simply to the tens of thousands who once worked here, as ‘The Steel’.

Even now, with the giant plant closed down and covered with weeds, Bethlehem Steel is an imposing sight.

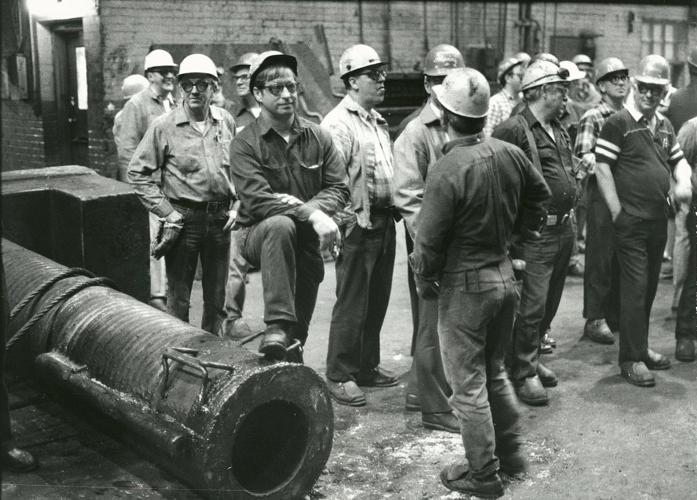

In its heyday with the blast furnaces running seven days a week, the heat and noise was a cacophony: “I remember the first day I was on the job and I was like ‘this is hell’”, recalled Guillermo Lopez, a millwright in the coke works, “smoke and fire, it was just incredible. I almost ran out of there, it was like a dungeon.”

Bethlehem Steel Corporation started out far more modestly: drawing on the abundant anthracite coal fields of Pennsylvania, the Bethlehem Rolling Mill and Iron Company began by making railway rails during the Civil War. By the 1870s, the company was fitting the US Navy with steel armour plating and guns. But it was the invention of the patented ‘Bethlehem Beam’, an Ɪ-shaped steel beam that transformed the company and the American skyline. This steel beam could be made longer, stronger and cheaper; it allowed skyscrapers to reach new heights, and bridges to traverse wider rivers and could be found in every American city.

The heart of the old Bethlehem Steel plant were the giant blast furnaces, which today are the most striking of the ruins. Several hundred feet high, the furnaces were where pig iron, coal, iron ore and limestone met heated pressurised air to forge the steel. The furnaces ran continuously, and at night the flames could be seen twenty miles away. Working here required fortitude.

“It takes uncommon talent, a strong body, and a mind that knows no fear to be able to transform piles of red dirt and scrap into the molten metal that is poured, rolled and pounded into the various shapes that support the mainframes of civilisation,” wrote Pulitzer Prize winner and reporter for the Bethlehem Globe Times, John Strohmeyer, in his account of the collapse of the plant in ‘Crisis in Bethlehem.’

Exploring the ruins today amidst the rusting machinery and weeds, it is hard to picture the sounds of an industry that built battleships and skyscrapers. As Strohmeyer described first hand, it was a ‘hellishly hot place where the air was dirty, the noise ear-shattering and a mis-step on a hot coke oven could be fatal.’

Between 1905 and 1941, five hundred people died working at Bethlehem steel, thousands more were injured, maimed by burning metal, toxic gases, and the lethal fast moving machines. “I almost went down in the fire,” recalls Frank Furry, a coke and ore dumper. “If it wouldn’t have been for my buddy standing right in back of me, he caught me. Otherwise I would have bought it, sure thing.”

The shifts were as long as they were hazardous. Joesph Mangan, who Strohmeyer recalled as a ’sixty-eight year old, peppery leather-faced survivor,’ recalled how, “the heat goes up to 190 degrees when they push an oven. A guy wearing wooden shoes walks on the roof to open the oven door. A second guy pushed the coke onto a car, another guy catches it. They push thirty, forty, maybe fifty ovens…they push until they keel over. That’s where the stretcher-bearers came in.”

Despite the gruelling nature of the work, many workers were proud of making the steel that built American cities, and at a local level, paid for homes, sent children to college and created a strong community in the union halls and bars of south Bethlehem. Mostly immigrants to America, generations were born, worked and died in the shadow of The Steel. Family stories such as the Checks were common, where eleven family members worked an incredible combined four hundred and forty one years at Bethlehem Steel.

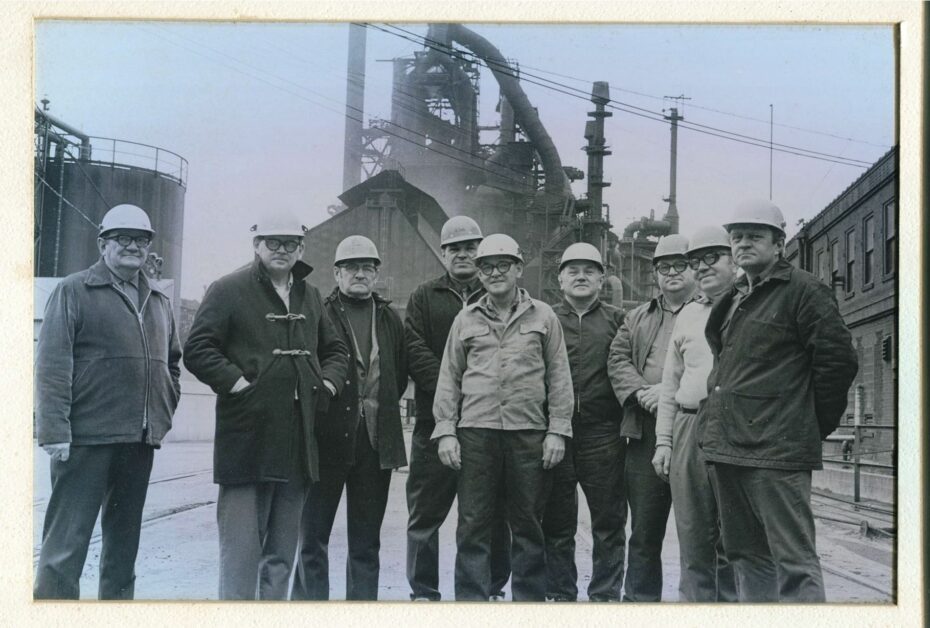

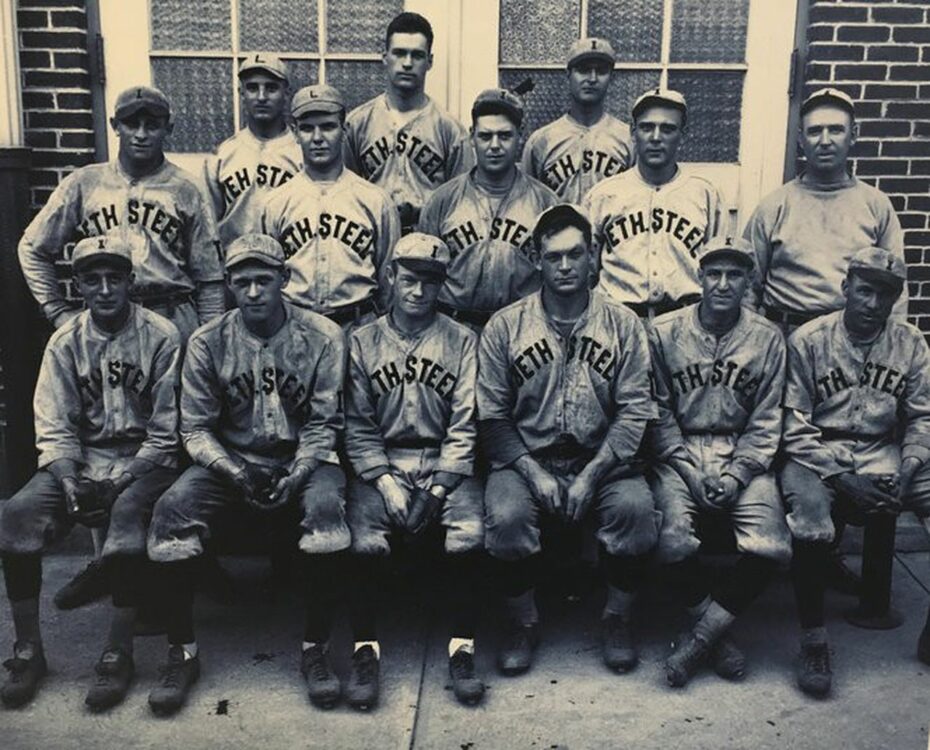

The company dominated life in south Bethlehem, from organising baseball teams, marching bands and even one of the first seated soccer stadiums in America, to the streets of family row homes surrounding the plant, who’s window sills, sidewalks and gardens required constant sweeping of the industrial dust spewed out of the open hearths.

Bethlehem Steel would also play a vital role in both World Wars, manufacturing millions of artillery shells and nearly a third of all the armour plating and heavy guns used by the United States and exported to European Allies.

By 1943, the company was constructing one battleship per day. “Bethlehem Steel was the most important to America’s national defence of any company in the past century”, wrote historian Lance Metz in the Washington Post. “We wouldn’t have won World War I and II without it.” As one of the largest defence contractors in America, over 25,000 women would work for Bethlehem Steel during the Second World War, helping to make ammunition, airplane parts, gun forgings and over 1,100 warships.

But half a century later, the unthinkable happened when this giant of American industry was declared bankrupt. Foreign competition and newer production techniques meant it was cheaper to import steel rather than use American-made. In 1982, Bethlehem Steel posted a loss of $1.5 billion, beginning to spell the end for the company that shaped much of the modern American landscape.

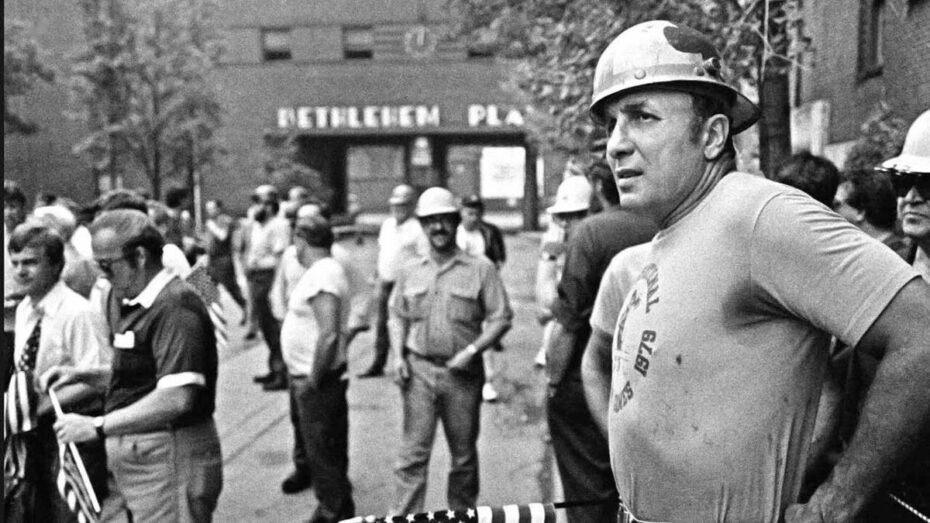

On November 18th in 1995, the last cast was made at Blast Furnace C. “When the saw-operator made the last final cut, the tears started to come down our eyes,” recalled beam yard saw operator Dave Schwartz. “And that was the first time we heard the mill silent. A lot of the guys you work with, you’re never gonna seem them again.”

It seemed inconceivable that the company that made the Empire State Building, Golden Gate Bridge and the Hoover Dam could ever fail. “I never would have believed it in my wildest dreams,” recalled Union leader Jerry Green who worked at the Steel for twenty seven years. “I thought Bethlehem was a giant and steel was king.” By 2001, the company filed for bankruptcy and was finally dissolved in 2003.

The effects on south Bethlehem were devastating as the collapse of the car industry was to Detroit, or the closing of the coal mines to any number of small towns throughout Pennsylvania. Still today, wander through the streets of South Bethlehem and you’ll find rundown houses and empty storefronts; the once elegant company head office was torn down in 2019.

It would have been all too easy to simply demolish the steel plant, but a local plan was hatched to create something remarkable: Bethlehem Steel would be preserved and the ruins transformed into a backdrop for one of the most unusual and visually arresting art spaces in America. Working with the nonprofit Artsquest, the City of Bethlehem created the ‘SteelStacks’ art campus, a ten acre site filled with art, sculpture, music and festivals.

Rather than let the collapse of Bethlehem Steel continue to decimate the city, the awe inspiring ruins were saved as a permanent memorial to those who worked here. Expert tour guides, many of whom worked at Bethlehem Steel are on hand to pass on the story of life at the plant; the Hoover-Mason Trestle, a narrow gauge railway that transported the raw materials to the blast furnaces was saved and turned into an elevated walkway similar to Manhattan’s iconic High Line.

Part of the brick infrastructure was turned into a casino, and the former Electric Repair Shop was transformed into the excellent National Museum of Industrial History. As SteelStacks explain, “rather than demolish the historic mill or walk away and let it fall apart, the community rallied around the iconic plant, working hard to bring new life to the former industrial giant.”

Explore the rusting remnants of Bethlehem Steel and it is hard not to be struck by the the scale of the ruins, a symbol of 20th century American industrial might and also its decline. Next time you’re walking around a major US city glance up at its oldest skyscrapers or bridges and the chances are they brought to you by Bethlehem Steel.