She is one of the most prolific photographers of the Victorian era, but much of her life remains a mystery. Clementina Maude, also known as Lady Clementina Hawarden, took up photography in 1857 and in seven years shot more than 800 images, mostly sun-drenched portraits of her daughters, from her home in South Kensington, London, before her death at the age of 42 in 1864. Although considered an amateur photographer, her work is now in many major collections and is still exhibited today. Hawarden used mirrors to create a body double and natural sunlight to light her shots, which was considered groundbreaking. And to the modern eye, it feels so contradictory to everything we know about the buttoned up mannerisms of the Victorian world.

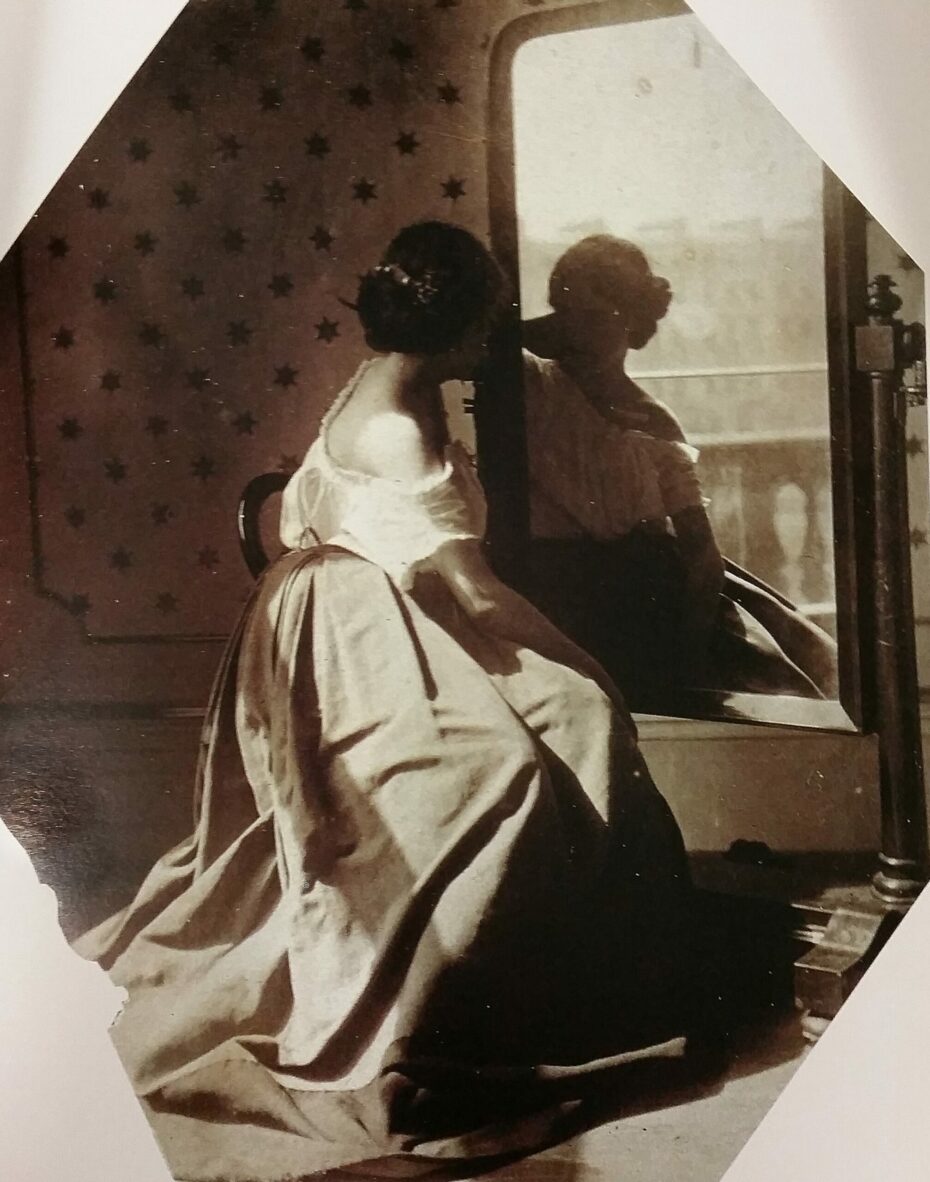

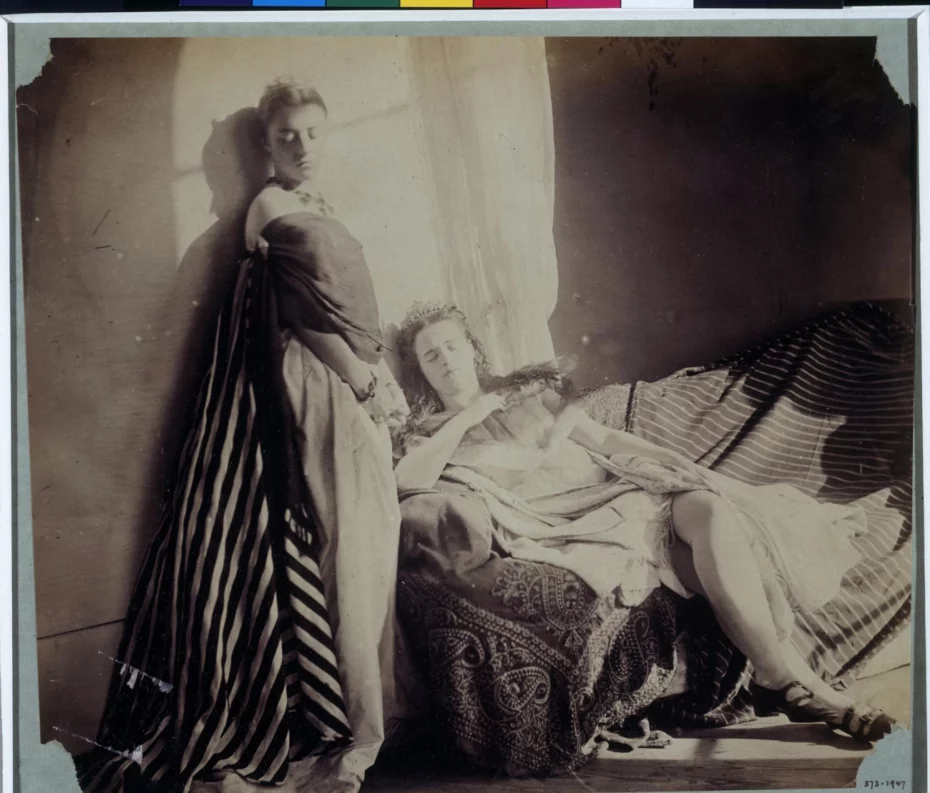

Hawarden was born into privilege as the daughter of Charles Elphinstone Fleeming, a member of Parliament and admiral who fought in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, as well as the Colombian and Venezuelan wars of independence. (Not much is known about Hawarden’s mother). In 1845, Hawarden married the 4th Viscount Hawarden and the couple had 10 children: eight girls and two boys. Despite having so many children, Clementina found time to set up a studio on the first floor of a luxurious home in South Kensington, London. And while she used her daughters Isabella Grace, Clementina and Florence Elizabeth as models, her work was not confined to simple family portraits. Furniture was removed to transform the dwelling into dramatic scenes. The girls often wore extravagant gowns or costumes, like for a nun; ancient royals like Mary, Queen of Scots; and a Spanish dancer. She experimented with techniques like using natural sunlight to light a picture, which wasn’t yet common, and a mirror to create the image of a body double.

Lady Clementina first turned to photography around 1856 on her family estate in Dundrum, in what is now Northern Ireland, taking stereoscopic landscape photographs that created a 3D effect. A few years earlier, English photographer Frederick Scott Archer had developed the wet-plate collodion process, using glass negatives coated in silver nitrate to produce sharp and vibrant images. (These notably also had a shorter exposure time.)

Hawarden became particularly fascinated with the new medium after moving to London. Her work was so contained to her home that the only time she took photos in person was at the Grand Fête and Bazaar to raise money for the new the Royal Female School of Art. In fact, one of her clients there was Lewis Carroll, who in addition to being a writer was also an avid photographer, particularly of children. (It wasn’t her only literary connection: A photo of her daughter Isabella Grace was used as a cover for Wilkie Collin’s famed mystery novel Woman in White).

Hawarden first displayed her albumen silver prints with the Photographic Society of London in 1863 – it was one of the first organizations of its kind, as photography was only about 25 years old at the time. While she was awarded a silver medal in the society’s annual exhibition that year as well as in 1864, she died of pneumonia at age 42 before she received the acknowledgments. Her immune system might have been weakened from exposure to photography chemicals.

She didn’t keep a diary and few of her letters are preserved, so her immense oeuvre provides some of the only insight into her life. She also wasn’t the only British female pioneer in the medium: Julia Margaret Cameron became renowned for her portraits of famous Victorians (like Charles Darwin), featuring soft backgrounds, as well as more creative work featuring mythological figures. Cameron, who was also a member of the Photographic Society of London, didn’t start making photographs until the age of 48, after her daughter had given her a camera as a gift.

Compared to their male peers, these women have largely been forgotten in the history of photography, particularly in terms of technical innovation. Luckily, Hawarden’s granddaughter Clementina Tottenham donated 775 of her portraits to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 1939. She in fact made the donation after visiting an exhibition on Victorian photography at the museum and being disappointed to not see any of her relative’s work. Tottenham ended up taking many of the images out of family portrait albums, highlighting that they had been intended for merely personal use: Most photos were given nondescript titles like “Photographic Study.”

Of course, this does not diminish their value as both works of art and scientific innovation and because of the insight they provide into life during this period. Later academics like Lillian Faderman and Carol Mavor have interpreted her work through an erotic and even queer lens, whether in the physical touch between the subjects, a sultry gaze or an evocative pose in a glamorous outfit. Some of Hawarden’s most powerful pictures feature her daughters looking at their reflections in mirrors. These represent the photographer’s ability to not only successfully remove herself from the frame but also suggest ideas around the female gaze that would be present in the work of female artists decades later.

In a Guardian review of a 2018 show on “the Victorian Giants” at the National Portrait Gallery in London, Jonathan Jones connects her to American photographer Francesca Woodman.

As Jones wrote, “Hawarden’s pictures of Victorian women have an intimacy that transcends time and a mystery that asserts the autonomy of her subjects. They are feminist, and gothic too, in their eerie atmosphere… Hawarden’s ultra-sharp yet shadow-rich prints create unresolved stories featuring women free to show who they really are.”