If you had lived in 1920s Paris, you would know who Barbette was. She was an icon of the night. A muse to the greats. A pioneer of queer. She might have built a career as a trapeze and high-rope performer in the United States, but made a name for themself in a very different milieu. As a “female impersonator”, Barbette captured the photographic eye of Man Ray and the literary eye of Jean Cocteau, and at the height of fame, would even go on to coach Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis with their career-defining roles in Some Like it Hot. Vander Clyde Broadway (a disputed last name), was born in Texas and attended a circus in Austin as a young boy, fascinated by the high-wire act. He would practice by walking across his mom’s steel clothing lines. As Barbette later told the New Yorker in a fantastic 1969 profile, “I knew I’d be a performer, and from then on I’d work in the fields during the cotton-picking season to earn money in order to go to the circus as often as possible.”

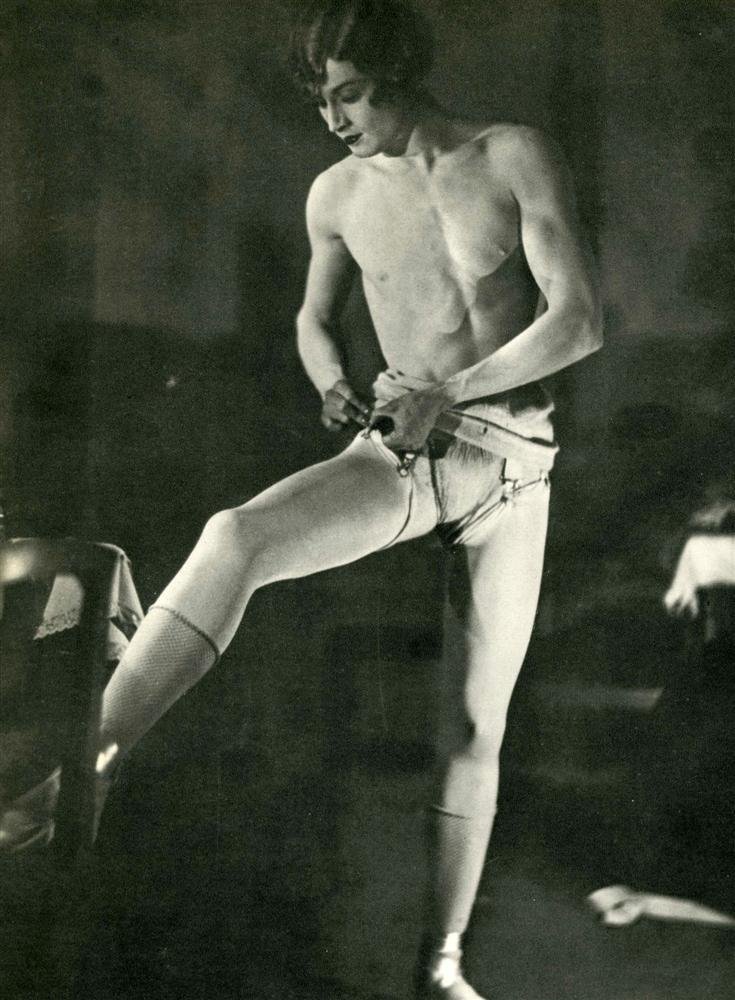

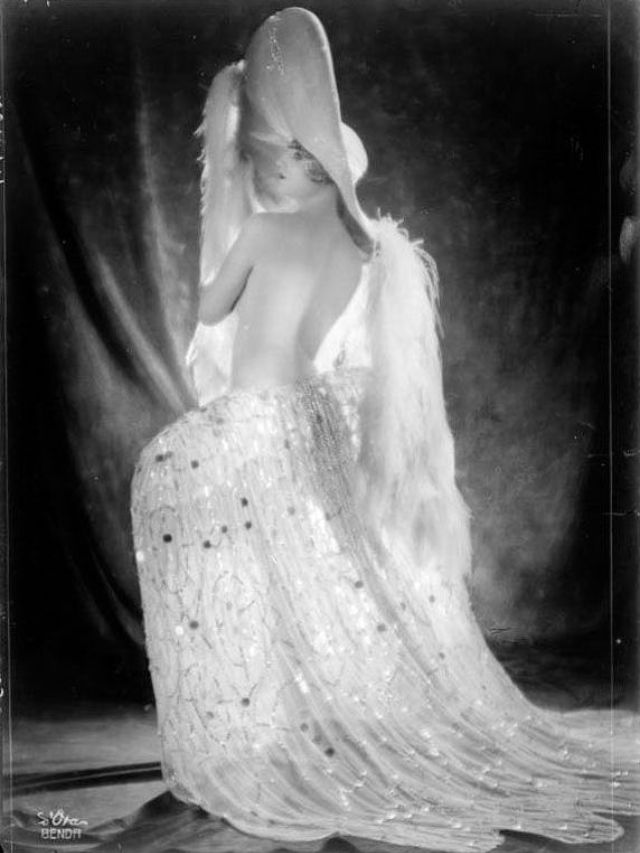

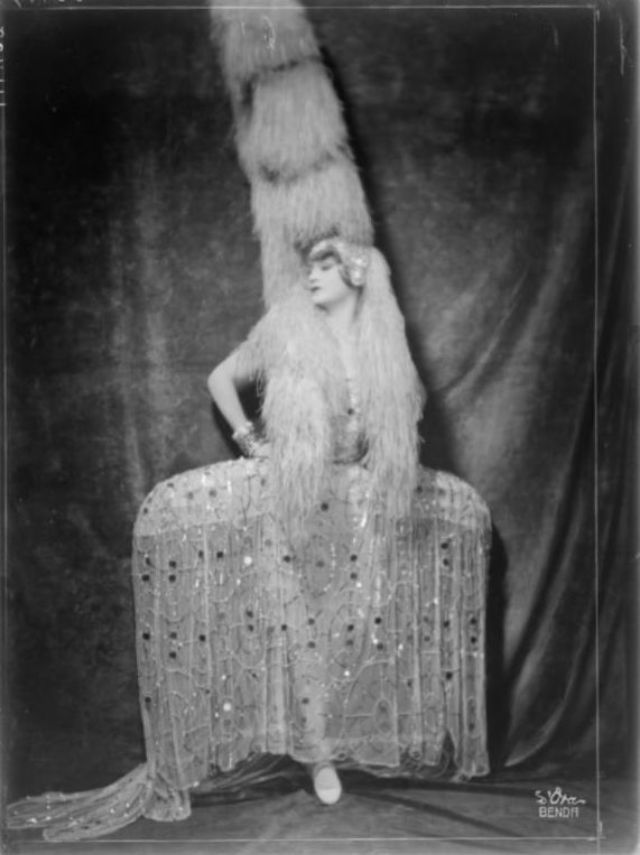

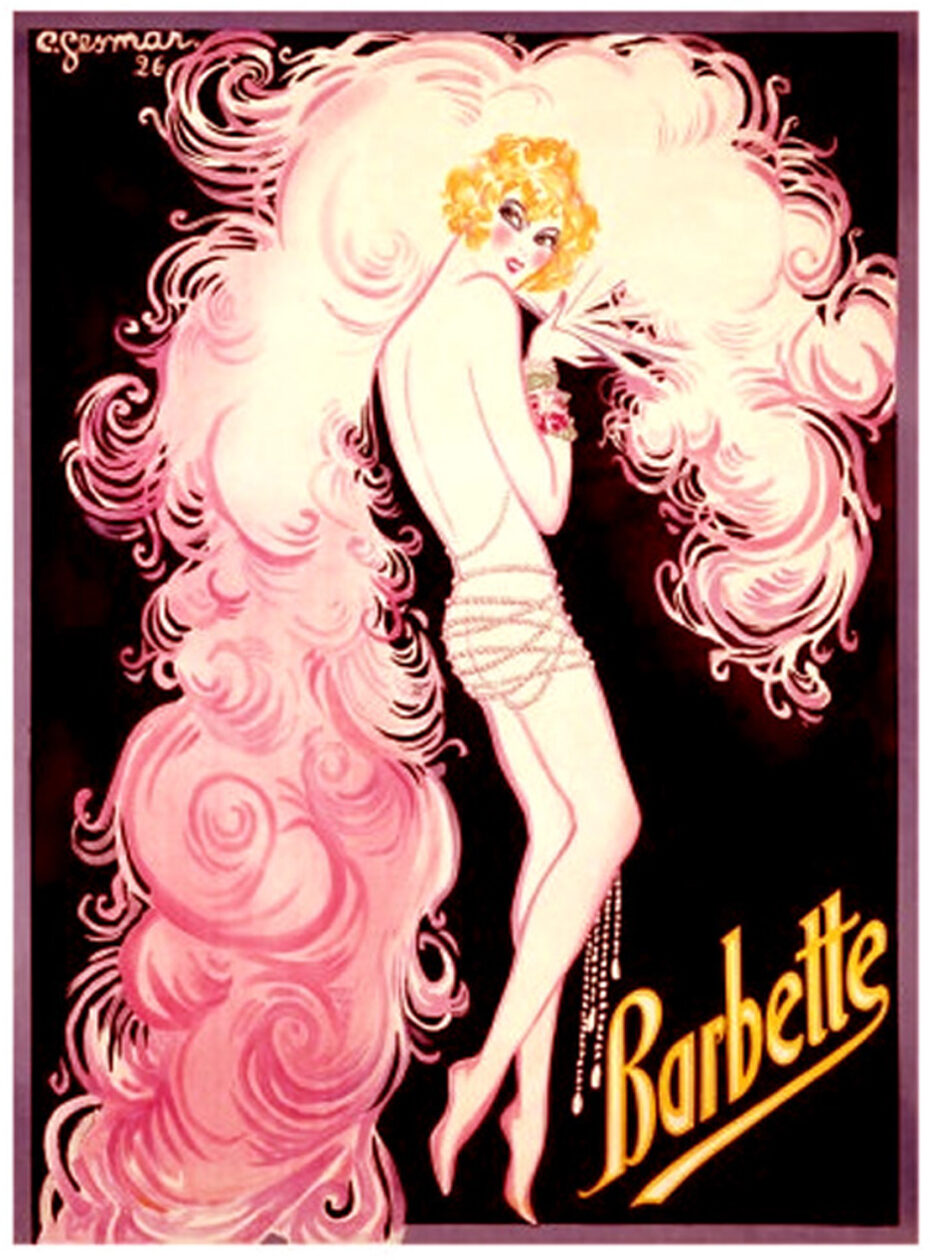

Broadway responded to a billboard ad looking for a replacement in the famed Alfaretta Sisters act. They asked Broadway if he would mind wearing women’s clothing, as “the plunging and gyrating are more dramatic in a woman” and he readily agreed. In the new role, Broadway went on to be part of Erford’s Whirling Sensation, performing a stunt in which the performer hung by his teeth wearing large butterfly wings. (Barbette would later become known for a signature ballgown and ostrich-feather hat.)

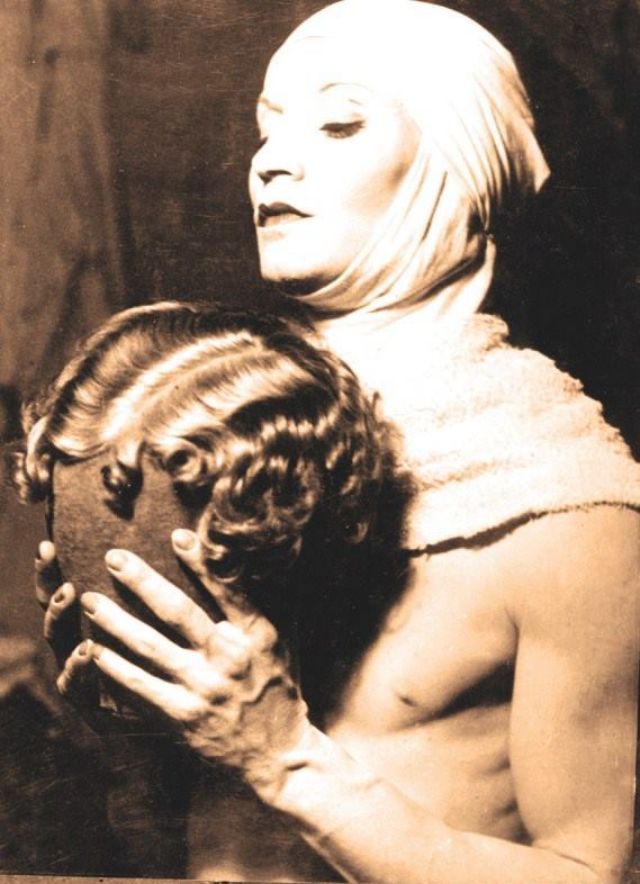

The Texan began developing a unique act, inspired by the magic not only of these death-defying feats but also of disguising his gender, only revealing he was a man at the end, taking off his wig and parading around with a masculine gait. As he told the New Yorker, “I’d always read a lot of Shakespeare and thinking that those marvelous heroines of his were played by men and boys made me feel that I could turn my specialty into something unique.”

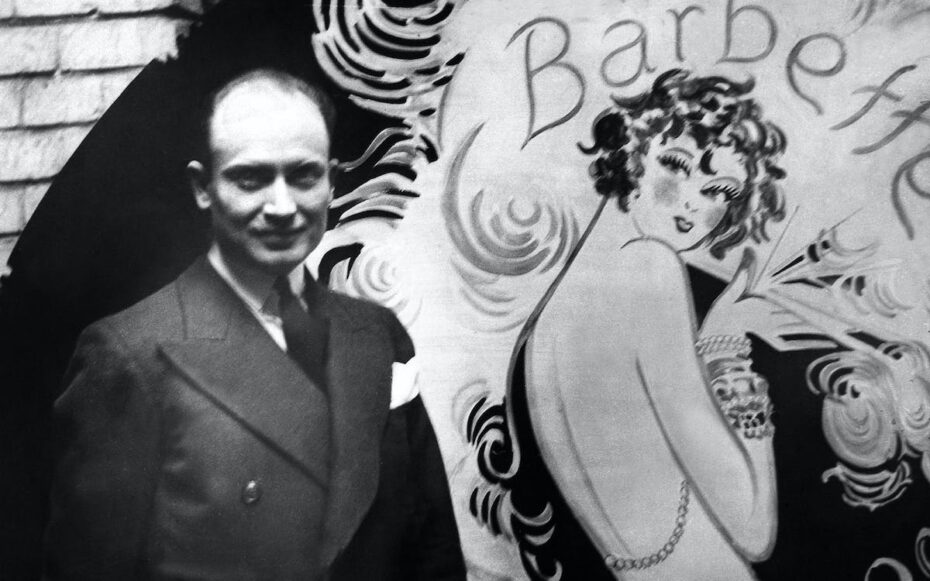

Broadway’s popularity as Barbette, a name he felt wouldn’t be too alienating for American audiences, led the way to Europe, where she became a sensation. In the fall of 1923, Barbette fell in love with Paris and Paris fell in love with Barbette. She became a regular feature at the Moulin Rouge and was quickly taken in by connected American expats, who introduced them to their circle of Parisian creative types, including Jean Cocteau, who was a fan of the circus and vaudeville. In a letter to friends, Cocteau described Barbette’s performance as a “theatrical masterpiece. An angel, a flower, a bird.”

In 1926, Cocteau wrote an influential essay on Barbette in the literary magazine Nouveau Revue Française entitled “Le Numéro Barbette,” describing what made the performer so enthralling: “The reason for Barbette’s success is that he appeals to the instincts of several audiences in one room and mysteriously brings together contradictory opinions. For he is liked by those who see him as a woman and by those who sense the man in him — not to mention those stirred by the supernatural sex of beauty.”

In a very French analysis, Cocteau argued that Barbette had transcended, both figuratively and literary, what could have simply been a gimmick done in bad taste: “He walked tightrope high above the audience without falling, above incongruity, death, bad taste, indecency, indignation.”

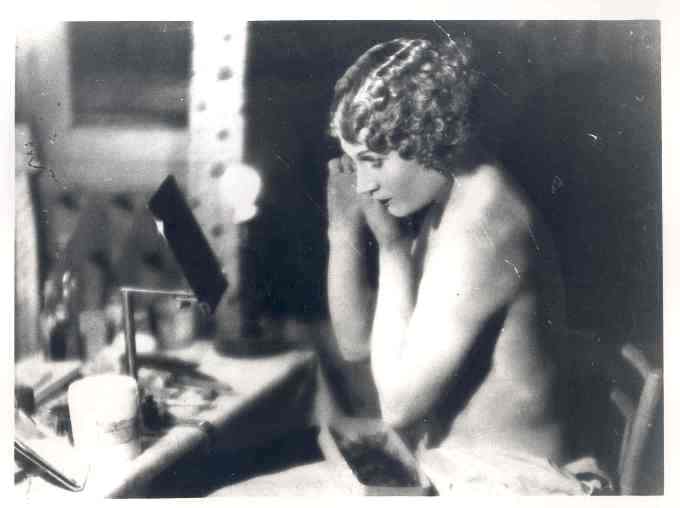

The essay was accompanied by photos that Cocteau commissioned from none other than the famed Dada and Surrealist artist Man Ray. In one, Barbette wears a towel around her waist in the style of a Roman statue, while others show the glamorous costumes and physical transformation for her performances. Cocteau, who also worked as a filmmaker, went on to feature Barbette in his 1930 avant-garde film The Blood of a Poet (which also includes the only movie appearance of famed photographer Lee Miller). Barbette appears with other actors in Chanel dresses in a theatre box, where they watch a card game that ends in suicide.

While Barbette traveled the world, including with the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus and supposedly with “28 trunks, a maid and a maid to help the maid,” the performer would return to their beloved Paris every year. By 1935, opportunities pulled her back to the United States, but some combination of a fall as well as pneumonia and polio put an end to a performing career, and Broadway was forced to spend months in the hospital and even to relearn how to walk.

But Barbette did not stop working, transitioning to serving as a circus artistic director and aerial trainer, choreographing the circus scenes in the Broadway musical Around the World, which Orson Welles produced. In the 1950s, Barbette was hired to teach “gender illusion” to actors Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis for the 1959 film Some Like It Hot. In the crime comedy, which went against the era’s prevailing Hays Code for including LGBT+ themes and cross-dressing, Lemmon and Curtis play musicians who join an all-female band to escape the wrath of gangsters.

Back home in Texas, Barbette continued to train new generations of performers but sadly committed suicide in 1973. The legacy of this 1920s star lived on most notably in the other artists she influenced. Barbette may have inspired a character in the 1933 German film Viktor und Viktoria, which includes a plot point around female impersonation, as well as Alfred Hitchcock’s 1930 film Murder! that focuses on a young actress in a traveling theatre group. A 2003 eponymous play also tells Barbette’s story, as well as a 1993 piece entitled Light Shall Lift Them by performance artist John Kelly, who has dedicated his career to shining a light on forgotten queer icons, most recently gay tattoo artist Samuel Steward. While Barbette was ahead of her time in more ways than one, what is most impactful about this story is how Broadway’s unconventionality was so openly embraced. “I wanted an act that would be a thing of beauty — of course, it would have to be a strange beauty.”