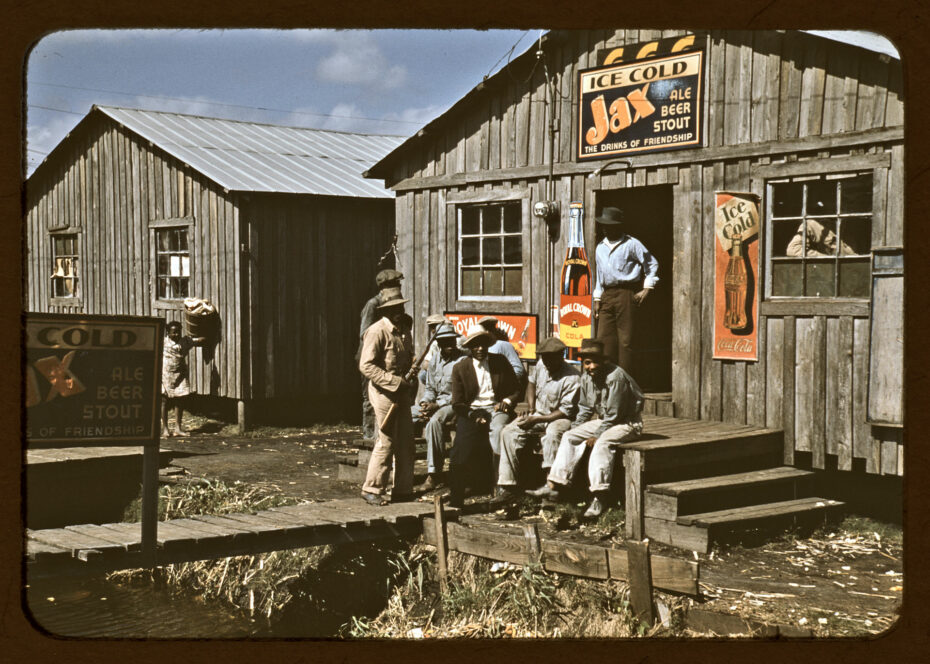

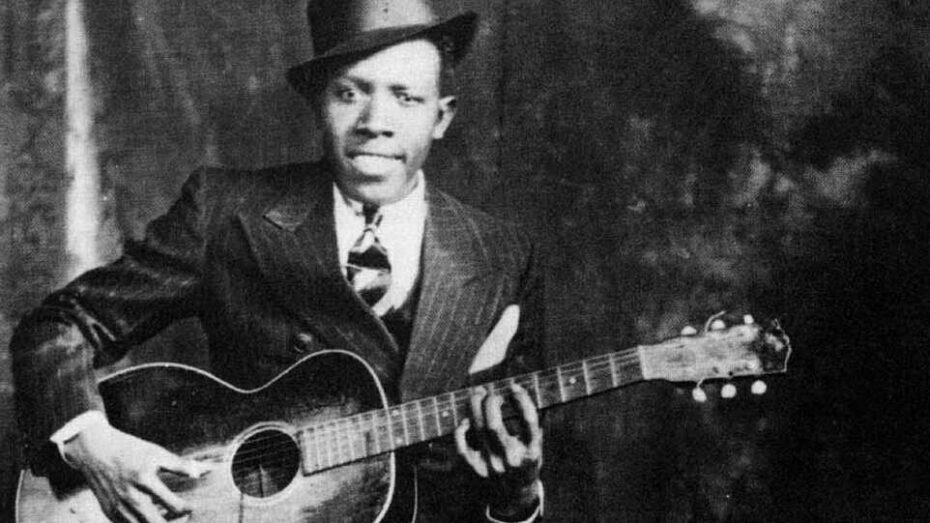

Before the Juke Box, there was the Juke Joint, a reverberating sanctum of the Mississippi Delta and the indefinable heartbeat of southern African American culture. The traditional Juke Joint seems to have grown out of the landscape more than it was constructed. A ramshackle collection of lost and found, partner to the barrel house and second cousin to the shotgun shack, the Juke Joint was a place to shed the shackles of slavery and the Jim Crow laws of the post-emancipation proclamation. Blues pioneers would ‘cut their teeth’ there; legendary but often forgotten names like Son House and Charlie Patton. “The first ever rock star” (as described by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame), Robert Johnson, was reportedly poisoned in one and BB king risked his life to save his guitar from a fire in another. Only a handful now remain; gone are the days when Juke joints were scattered all over the South. The Juke Joints were the place to meet, tell stories, dance, gamble, and drink moonshine liquor until the early hours.

After 1865 and the abolition of slavery, newly freed African American men and women of the South were still subject to Enforced segregation. Sharecropping and poverty forced many families to be tied to the land and had to work relentlessly just to survive. Around these conditions, the first Juke Joints would emerge. The Word ‘Juke’ may derive from the African word ‘Juga’ meaning bad or wicked or to lead a disorderly life. Initially no more than debilitated wooden structures, they became the life and soul of the South. Later, many were built on crossroads and near train tracks to attract the transient and nomadic workers of the Depression era.

It was in 1937 that the coin-operated record-playing machines that would become so popular from the 1950s onward would adopt the name ‘Jukebox’ after the influence of the Juke Joint. Traveling musicians would move from one to another, often with just a hat or guitar case to collect money from the crowd. ‘Jukes’ would appear around temporary work camps, in rural locations, and in the back and beyond of nowhere.

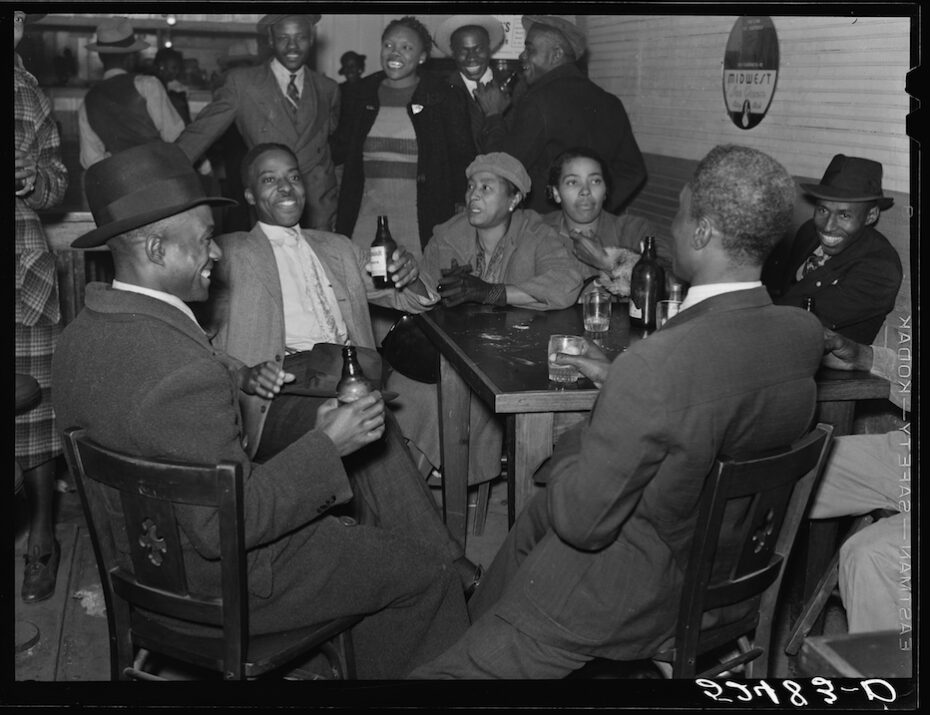

These locations offered some privacy and freedom from the restraints of the time. Fuelled by the local white lighting and corn whisky, the party would begin until the whole shack was shaking. The Juke Joint would be a catalyst in the development of Black music in America; from Blues to Ragtime and onward to Rock and Roll, and the never-ending influence on todays music.

Elvis Presley would peak through the slats of a Juke Joint in Shake Rag, Tupelo Mississippi, and go on to change the course of popular music, so affecting was the rhythm and resonance vibrating from the structure.

You can count the the number of original juke joints left in the country on your hand – and most of them are in Mississippi. One of the most authentic ceased operating as recently as 2016 when its owner, Willie “Po Monkey” Seaberry died.

A humble shack located in a dirt road in the tiny Delta hamlet of Merigold surrounded by old cotton fields, Po’ Monkey (also known as Poor Monkey’s) was founded and built by Willie in the 1960s and named after his childhood nickname. It was decorated with Christmas lights year round, dolls, disco balls and toy monkeys hung from the low ceiling. The Oxford American Literary Project visited the Juke Joint and interviewed Willie before his death in 2013. “Poor Monkey’s has given generations of music loving customers an experience that is uniquely Southern and uniquely American” noted the filmmakers who documented the visit on film. “It was, after all, in places like this where American music was born”…

The contents of the building were sold off at auction in 2016, but it still stands, silently now, at 99 Po Monkey Road. The shack has a National Register of Historic Places marker in front, and as a key landmark of the Mississippi Blues Trail, the buyer had plans “to share the cultural cache with the public”, but no recent developments have been reported.

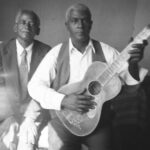

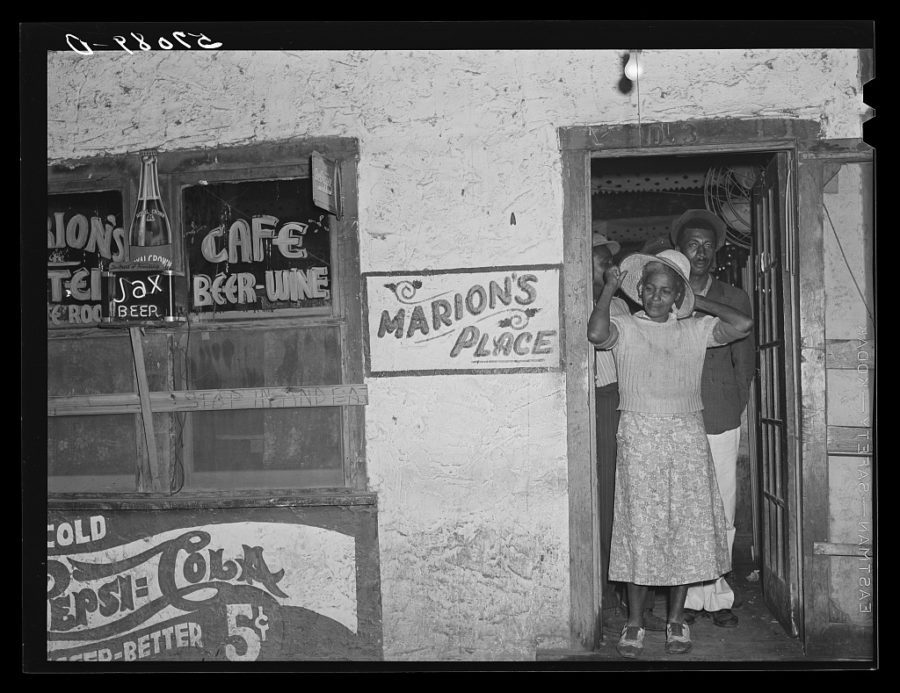

In places like Bentonia, Mississippi, where one of the last few Juke Joints still stand, the Blue Front Café is the oldest continuously operating establishment of its kind. Owned by Jimmy “Duck” Holmes (pictured above right), it opened its doors in 1948 before Jimmy took over from his parents in 1970. It’s a cinder block cultural time capsule. The Blacks Keys shot their video to ‘Crawling King Snake’ there, and in the 90’s it was used for a Levis’s commercial. Originally it serviced the workers from the cotton fields around Yazoo County, and in the height of the work season, it would stay open for 24 hours a day. If only the walls could talk, they would howl to the rhythms of the famous cast of blues musicians that have played there – people like Skip James, Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2, and Jack Owens to name but a few. The walls are now covered with these ghosts of the past, a tattered reminder of gigs come and gone. Jimmy himself isn’t just the proprietor of the Blue Front, he’s a Grammy-winning musician in his own right and an exponent of the Bentonia Blues style that sprang up in the area in the early 20th century.

On a Crossroads in Clarksdale, Mississippi sits Reds Lounge, Flanked by the river and a graveyard. It’s a true Juke Joint; dark, cramped and sweaty, people shoot pool while guitars growl, and a rumbling voice cries out from the past. Walls are layered with memories and miscellanea. Owner Red Paden was born into it and is a champion of Blues. And if you can count Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin as a patron you must be doing something right. More Blues players have come from this area than anywhere else and today tourists flock to the blues trail to try and catch some glimpses of the past.

Red often puts on events to help the community with festivals and charity gigs. And that’s what The Juke Joint seems to represent these days, a community space where all are welcome. The Juke Joint proprietors seem to have that all in common; a reverence for the place they grew up and a wistful longing for a “simpler” time. Over the road from Red’s is Ground Zero, owned by actor Morgan Freeman. It’s an ode to the traditional Juke, with mismatched furniture, crumbling brickwork, and walls plastered with posters but has a traditional menu, a website and Wi-Fi. Some things it seems can’t be recreated, and maybe they shouldn’t because if it doesn’t look like it could collapse at any time under the sheer weight of time and music, is it really a Juke Joint?

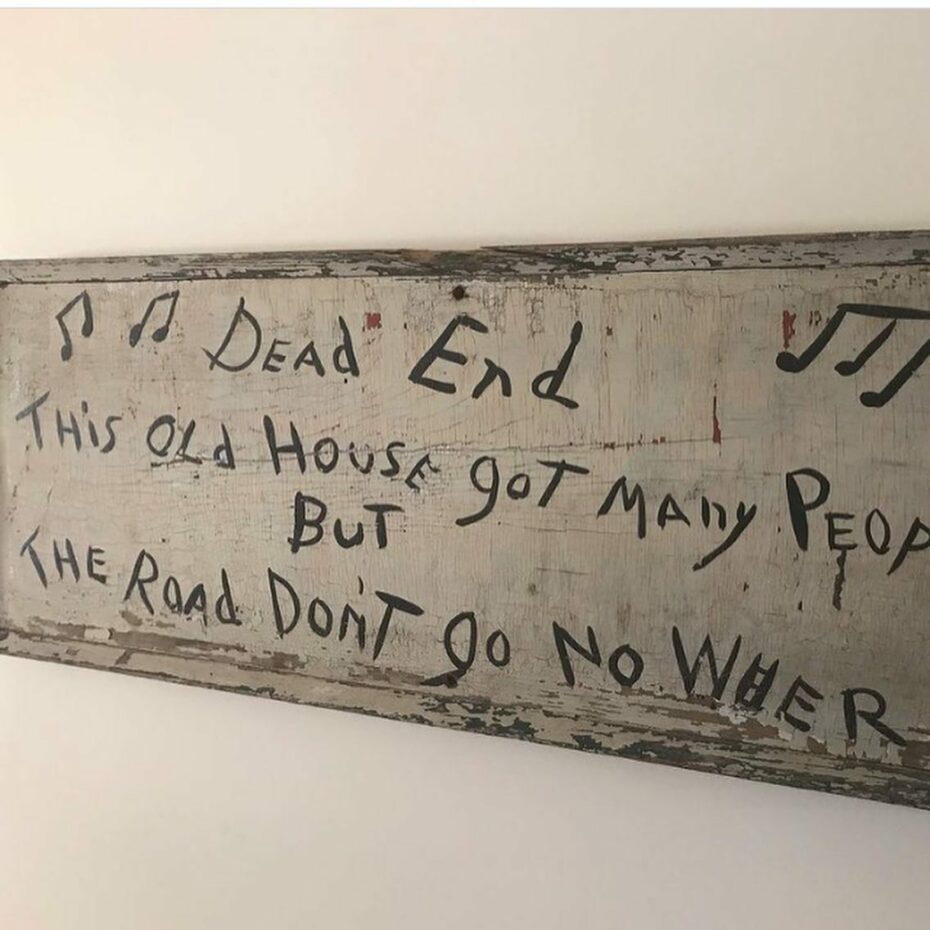

Early 20th century sign, possibly from a juke joint.

The first decline of the original Juke Joint came with the migration of rural workers to the big cities and the appeal of more jobs and a better life. Automated cotton-picking machinery had entered the industry and left a work force obsolete. The musicians who had given the Juke Joint its soul would burn out, retire, or relocate and invent the electric blues, and times would change. Music continued to evolve and young people just weren’t as interested in the raw and gritty source. These days, you are more likely to find the White middle-class and European tourists visiting the remaining juke joints in Mississippi than the what would have been the traditional crowd of laborers, field hands, and sharecroppers, but the pilgrimage to the delta and the Juke Joints can be a right of passage for many aspiring blues musicians and aficionados. Now with only a few solitary bastions of the culture holding the flame, the writing seems to be on the wall for the Juke Joint. And when eventually the levee breaks and progression carries the last of the Juke Joints out of collective consciousness, what will remain will be the echo of the times that were had, and the songs that were sung.