It should come as no surprise that some of the world’s most fascinating collections are found in churches. But today we’re not talking about Florence’s abundance of Renaissance murals or the Baroque masterpieces in Rome. Arguably the most intriguing religious collections are the ones overlooked by art historians, created by self-taught local artisans, donated by nameless worshippers and accidentally curated by devoted pilgrims and monks. We’re looking at the enchanting (and sometimes macabre) world of ex-voto.

The thing is: when I started looking into ex-voto, I wasn’t prepared for the vast range of votive objects that exist, sometimes exceeding the confines of religion. The Latin term (literally meaning “from the vow made”) refers to an offering of an object for display without the intention of recovery or use in a sacred place to gain favour with supernatural forces (saints, spirits and deities)…

Objects customarily gifted to Christian churches and shrines by the faithful throughout history come in all shapes and sizes around the world as I would discover. A votive offering can be something as plain as a crucifix, but ex-voto objects as we understand them today can get a lot more creative, ranging from miniature silver sculptures to folk art paintings. They can also take on more obscure forms, from braids of hair to prosthetic limbs – all offered as expressions of faith, thanks for protection and sometimes, for miracles…

Very often, they end up looking like contemporary art exhibits, wouldn’t you say?

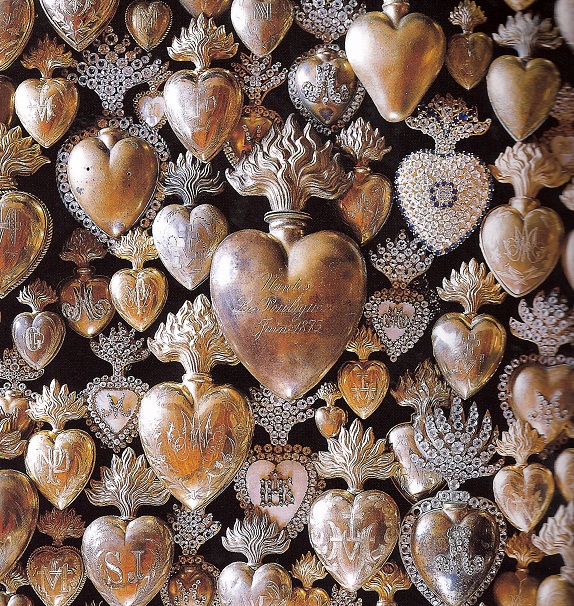

One of the most familiar forms of ex-voto is the Sacred Heart, a flaming and wounded heart sculpture, often depicted with a crown of thorns, alluding to Jesus’ death and divine love.

You’ll usually find them, along with other ex-voto objects, displayed on the walls in side alters, or surrounding pilgrimage sites like a kind of accidental exhibit of sacred art, collectively curated by the people.

They’re procured from religious shops, where worshippers (or collectors) can purchase them to be hung in churches or displayed decoratively at home. Once gifted to a church or sacred place however, ex-voto is not supposed to be removed from that location. Older ex-voto found in the antiques trade tends to come from private collections and deconsecrated churches.

Ex-voto collector Mariolina Salvatori makes an interesting point about collecting such religious artifacts as objets d’art: “It has been argued that collecting them, writing scholarly articles about them, displaying them in museum exhibits, appropriates and does violence to them. But what this argument does not acknowledge is the extent to which collections, scholarship and museum exhibits can ignite respectful and responsible appreciation of cultural expressions, and artifacts that would otherwise be ignored or remain marginal.”

Examples of ex voto sacred hearts range from copper to silver to embroidered, encased and bejewelled. Both eBay and Etsy has an interesting range of charms, medallions and wall hangings, ranging from a few dollars to upwards of a thousand.

Alongside silver and metal hearts, we can also find plaques that take on the shape of body parts to symbolise a miraculously healed foot or even a successful childbirth.

At the Basilica of Our Lady of Aparecida, Latin America’s most popular shrine, people leave ex-voto objects ranging from motorcycle helmets to guns to wax body parts either to ask or give thanks for the saint’s help in overcoming illness, accidents or other hardships.

Parisian ceramicist Lise Meunier is inspired by ex-voto of this kind (you can see more of her work here). Meanwhile, in the church of Notre-Dame de la Garde in Marseille, you can find ex-votos in the form of model boats, historically given to the church by sailors, merchants or families of soldiers, praying for their safe passage.

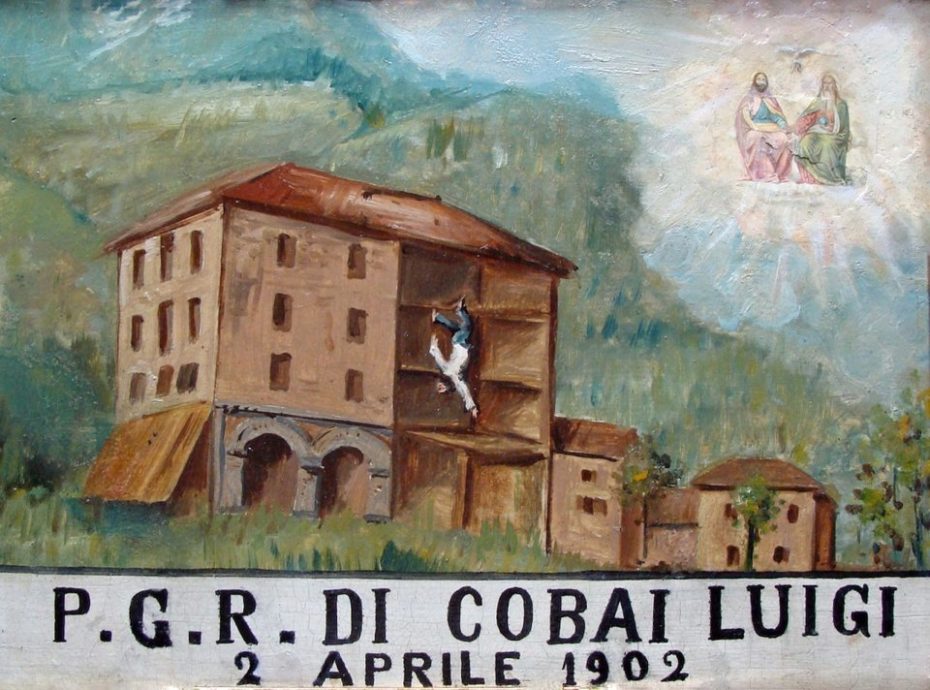

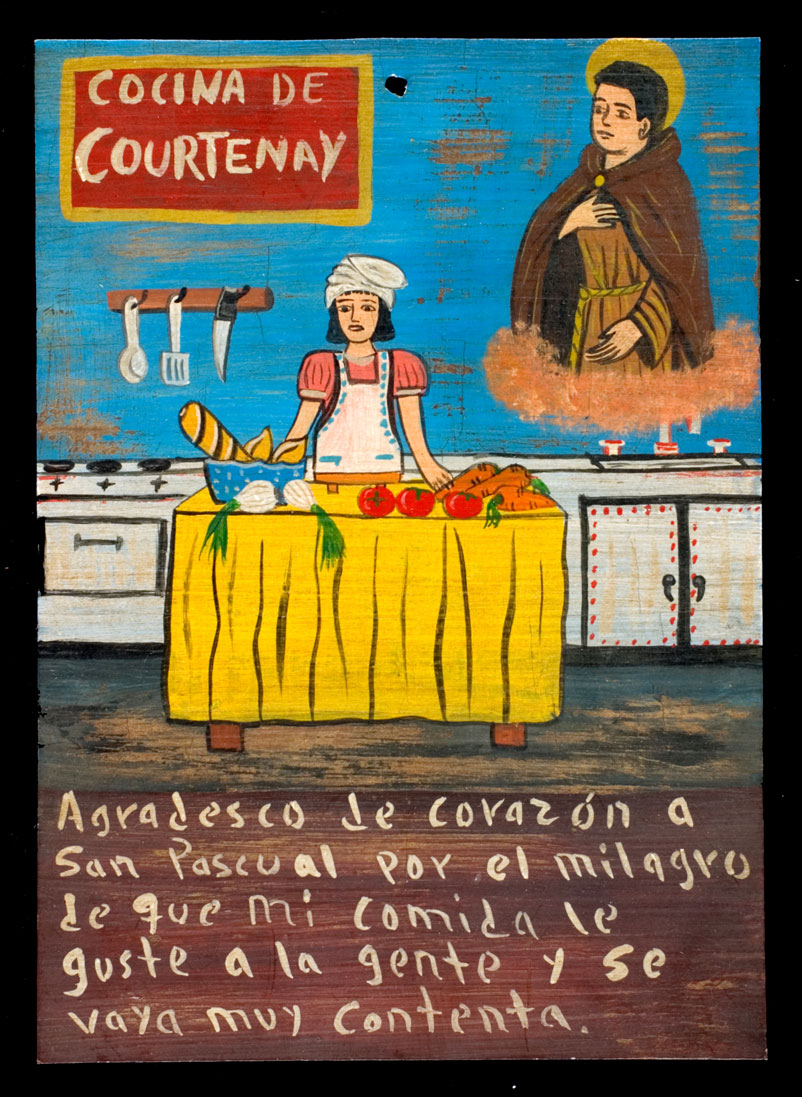

Another major form of ex-voto is the painting, a tradition that originates from 15th century Italy. Wealthy patrons commissioned skilled artists to create ex-voto paintings depicting a miracle attributed to the helper, which would be hung in their private chapels. The practice became so popular with the middle and working classes that it eventually fell out of fashion with the elite and took its place as a “low art”, produced mainly by self-taught artists.

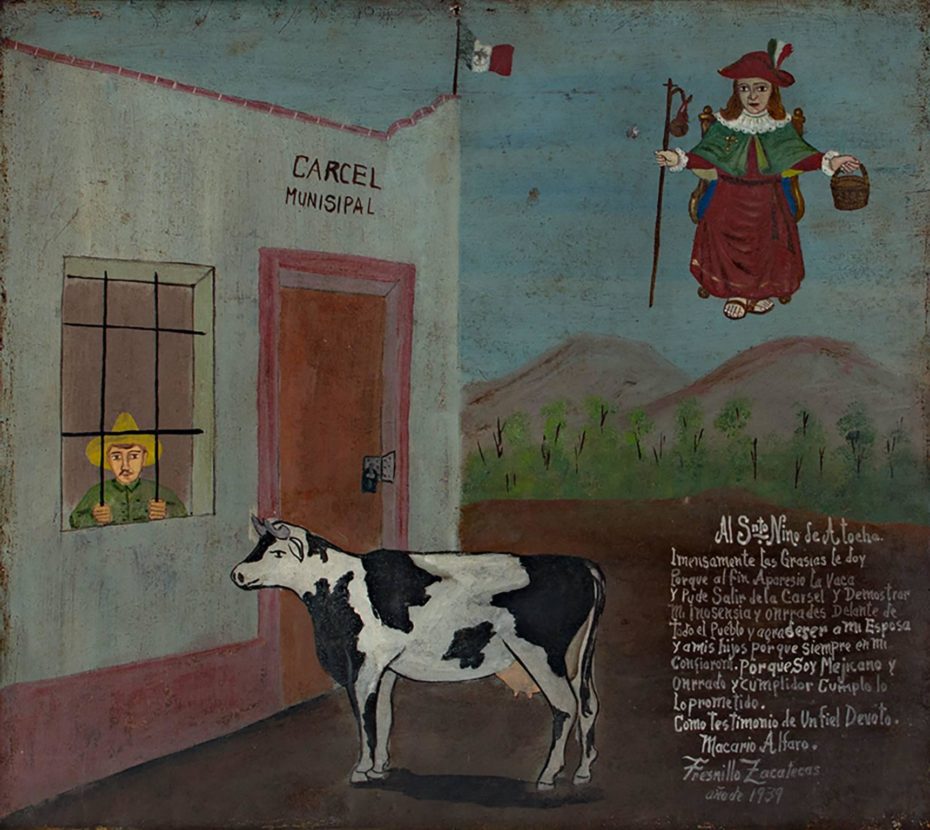

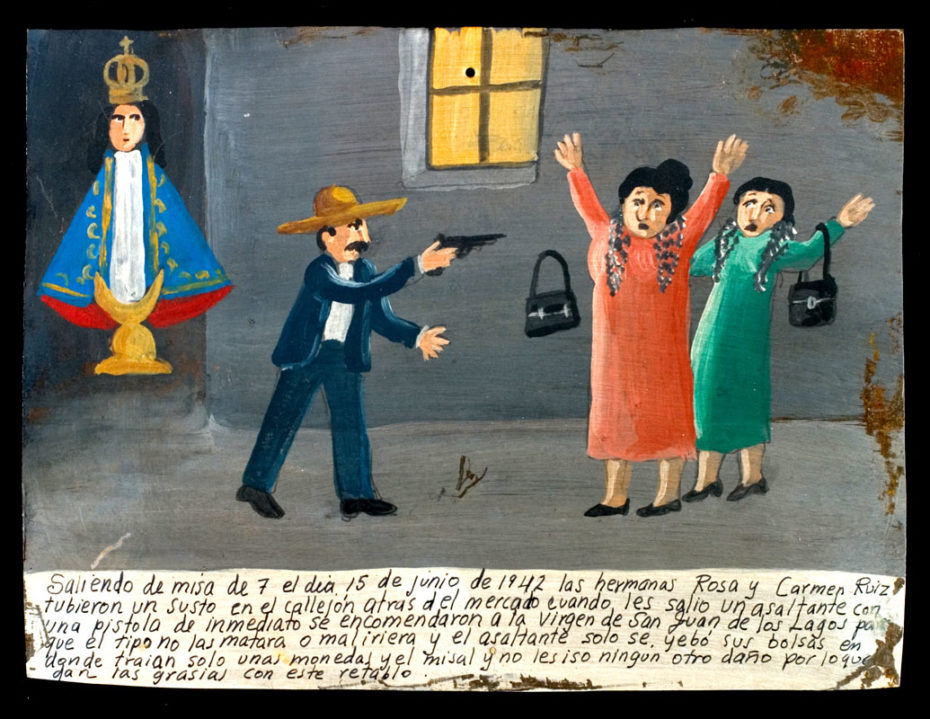

Ex-voto paintings spread across continents wherever Christianity flourished, particularly in Mexico. They would become a recognised genre of folk art, known as “retablos” (which translates to “behind the alter”), usually produced on tin, zinc, wood or copper for use in home altars.

Subject matters can range from the injustices endured by the working class, but ex voto paintings can also take on a surprisingly violent nature, depicting fatal accidents or crime scenes:

This style of painting greatly influenced none other than Frida Kahlo, who held many retablos in her personal collection. Kahlo and Diego Riveras had a collection of more than 1000 Ex-Votos which can be seen in the Blue House in Mexico City.

With the advent of photography, the tradition of commissioned painted ex votos in both Mexico and Italy is dying out. Prayer cards, photos, and written notes are cheaper to commission than paintings, while ex voto paintings are rare, and can fetch a pretty penny on the art market. One 19th century Mexican ex voto painting on 1st Dibs is currently asking upwards of $9000.

But if you’re on the hunt for ex voto collectibles that fit within your budget, Mexico is no doubt the best place to start.

“Unlike Italian culture, Mexican culture has deployed several ‘popular’ ways of keeping alive, re-appropriating, and transforming the ex voto tradition,” explains collector Mariolina Rizzi Salvatori. “Ex votos as souvenirs, commercially produced and sold on the streets of Mexico; ex-votos embroidered by women living in small rural communities, mainly in central Mexico, who sell them to support their families; decorative uses of ex votos hung in homes, offices, public places or painted on room dividers, fire place screens, refrigerator magnets.”

Moving from Mexico over to the South of France, we turn our interest back to ex voto objects with the “Santi Belli”: moulded clay figurines, painted in lively colours, decorated with gold foil and often encased in glass domes. They were found on mantels in all Provençal homes during the nineteenth century and their name possibly comes from the Italian pedlars who sold them crying “santi belli” as they roamed the streets of Marseilles.

The Souleiado Museum in Tarascon Provence (in our Provence eBook) has a substantial collection of Santi Belli, as does the Hotel d’Agar outside of Avignon, a veritable curiosity cabinet open to the public. The intimate museum is also home to a substantial collection of paperolles, which might fall better into the category of relic over ex-voto, but nonetheless, I highly recommend taking a look, preferably in person, next time you’re antique hunting in Provence!

I’ll leave you to browse the ex voto marketplace or google the delights of Paperolles – happy collector’s hunting!