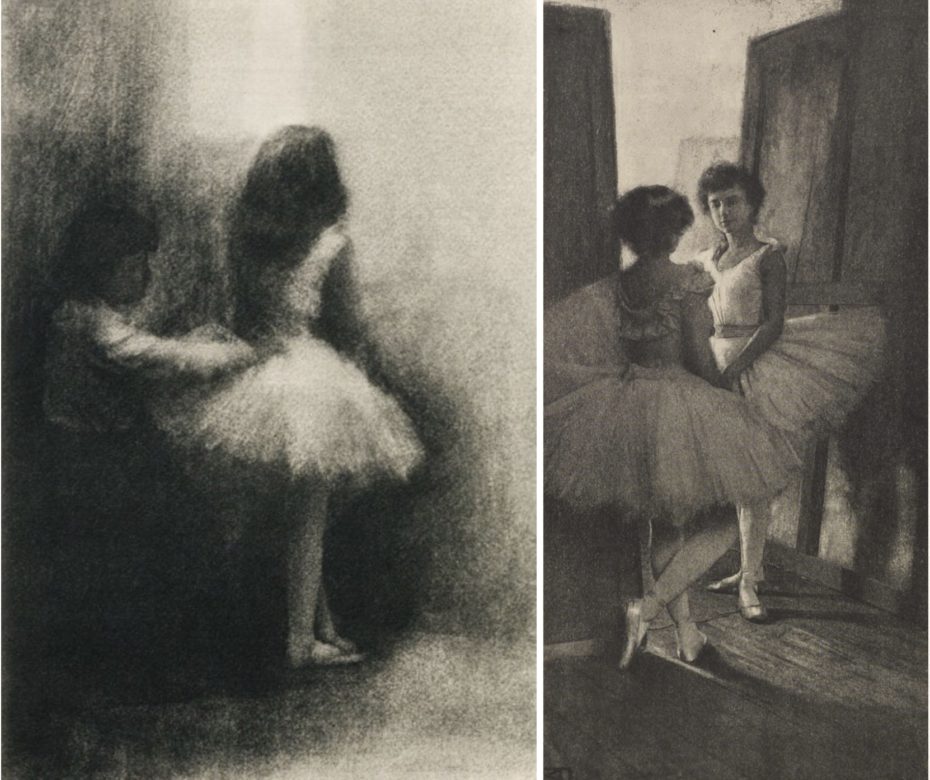

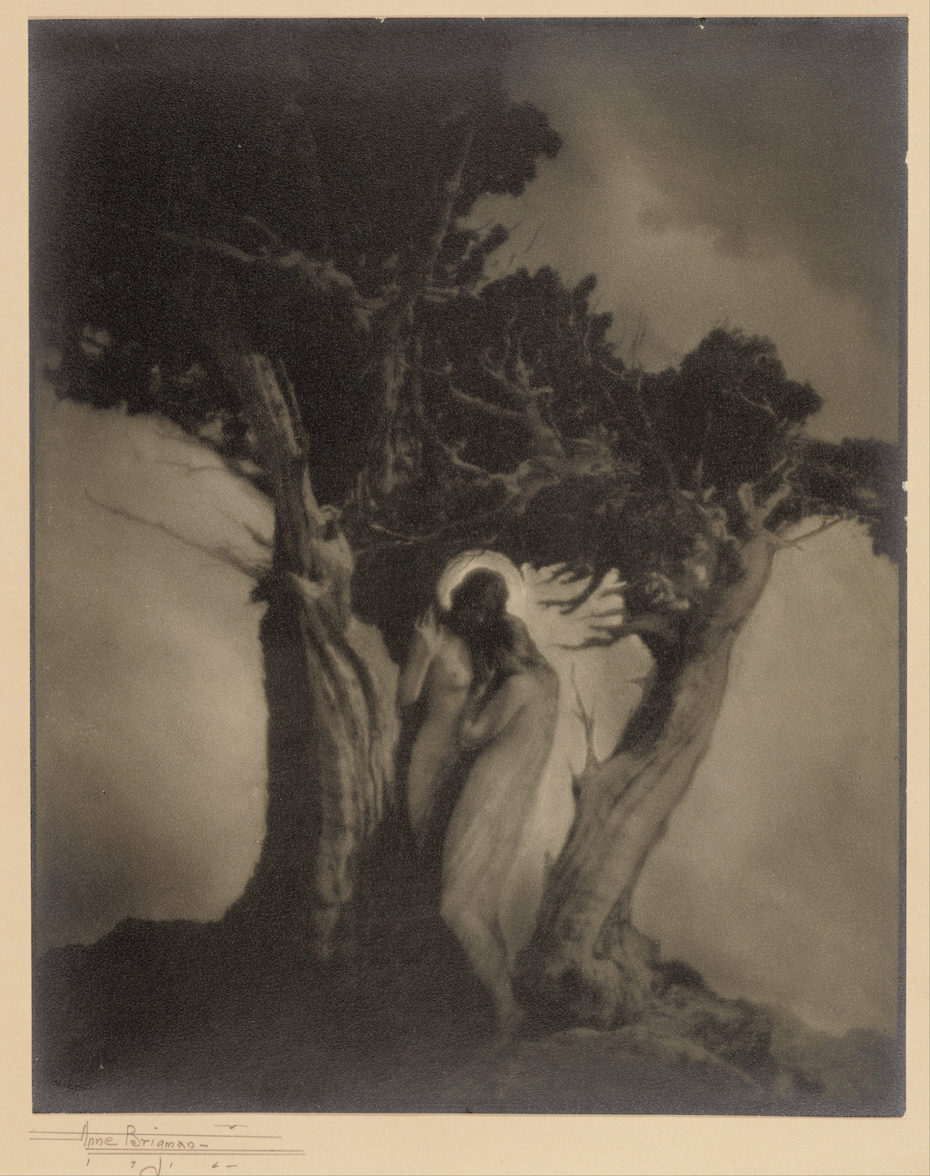

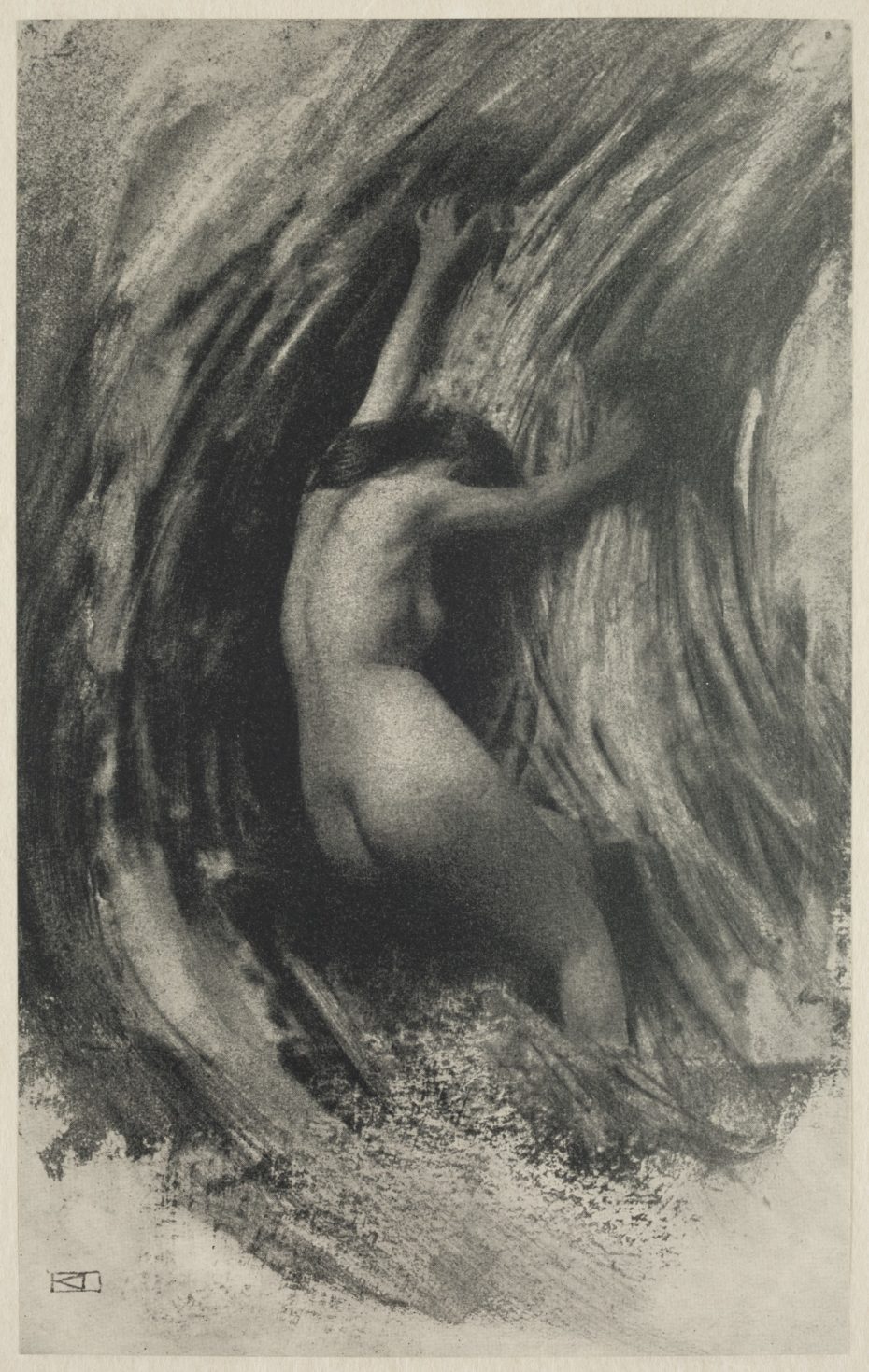

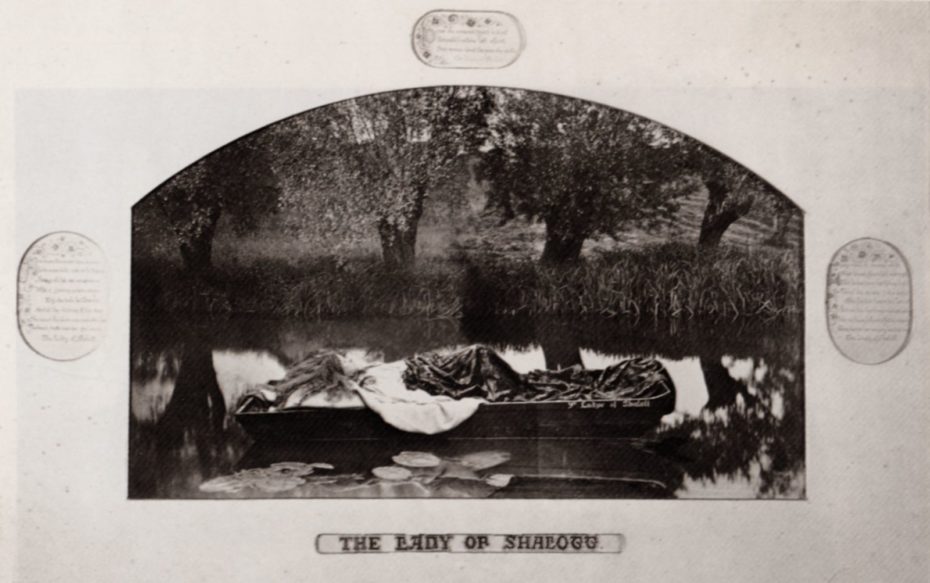

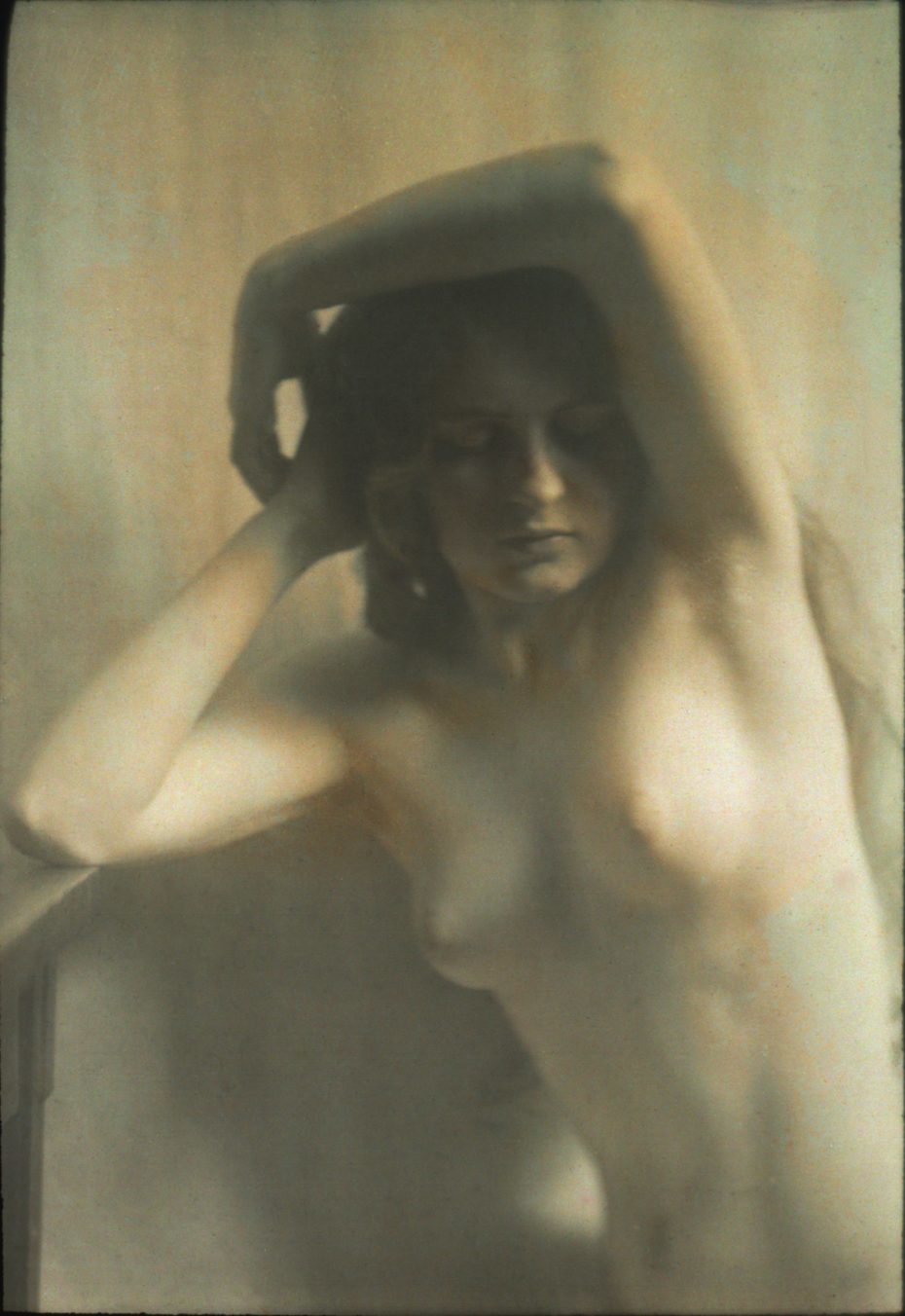

It would take most people a moment to figure out that the images above aren’t charcoal sketches by Degas or some other Impressionist artist. These are in fact photographs from the late 19th century, artfully manipulated to look like paintings. They were made at a time when it hadn’t yet occurred to most of the world that photography could be used to create an image rather than simply record it. Before Photoshop and machine-generated images, a little-known movement of creators used this curious aesthetic of photo manipulation to help photography find its place as a true art form. They were called the Pictorialists.

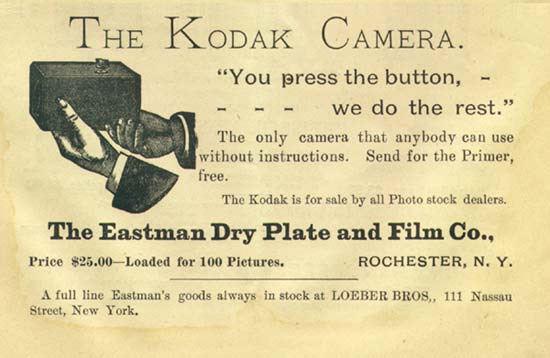

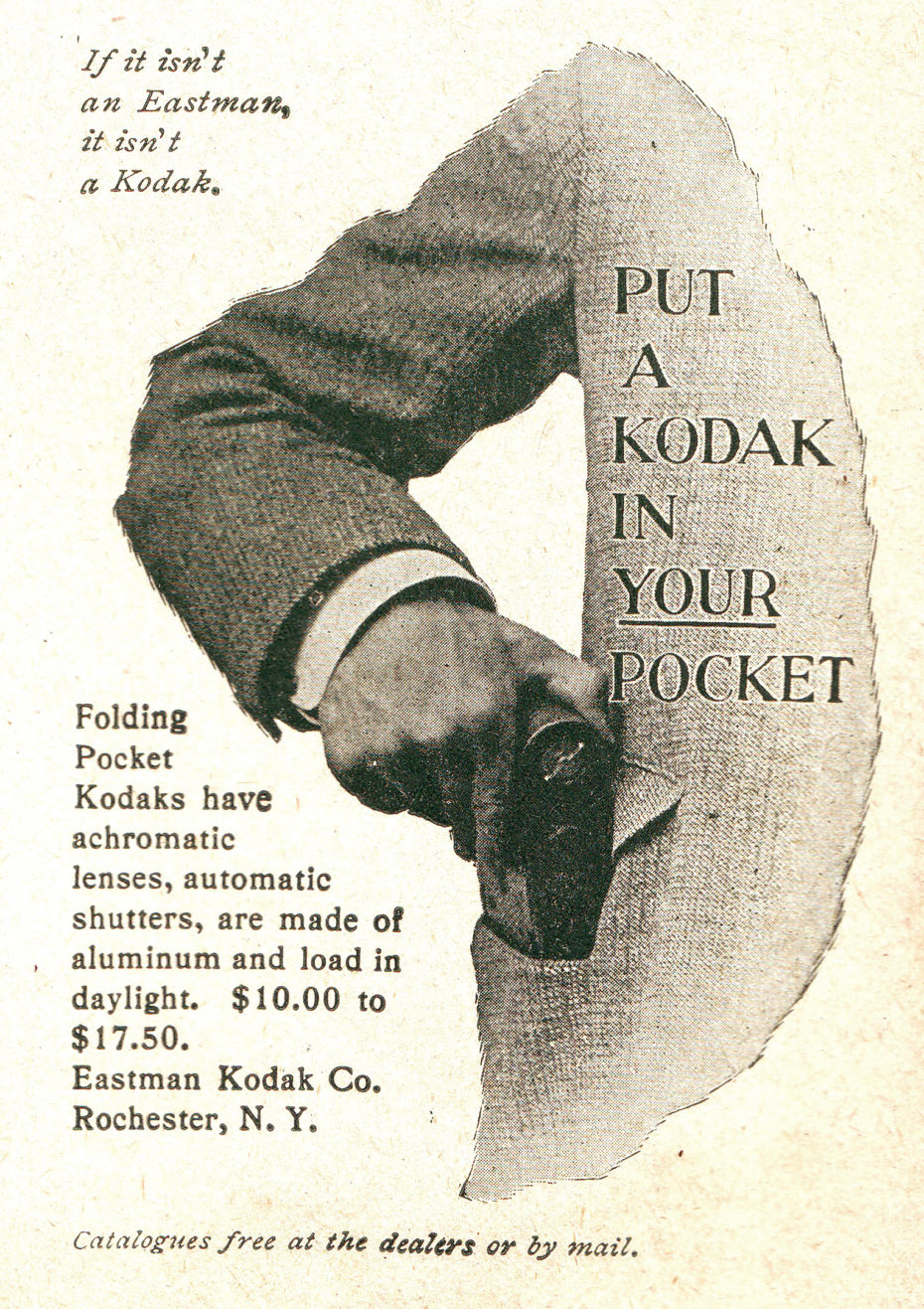

When Kodak introduced the first handheld camera in 1888 with the slogan “You press the button, we do the rest,” photography suddenly became one of the biggest fads in the world.

“Thousands of commercial photographers and a hundred times as many amateurs were producing millions of photographs annually,” explains Dr. Michael Wilson, the world’s foremost collector of 19th century photographs (who also happens to be the producer of every James Bond movie since Moonraker). “

“The decline in the quality of professional work and the deluge of snapshots (a term borrowed from hunting, meaning to get off a quick shot without taking the time to aim) resulted in a world awash with technically good but aesthetically indifferent photographs.”

Suddenly, everyone was a photographer and the amateur “point-and-shoot” approach undermined the artistic nature of photography . If anyone could take a photograph, how could it possibly be called art? The debate sounds familiar – like when photography went digital, and again most recently, when Instagram and its ready-made filters took over social media. Or even when photography was first invented, in 1839 Charles Baudelaire wrote a piece on how the medium was set to destroy art itself, since nobody would bother to make paintings anymore. Instead, painters were free to become more expressive and some of the best works in history followed.

Pictorialism was born out of this ongoing debate that began in the 19th century – out of photographers trying to “prove” their art and align it more closely with the attributes of great paintings. The movement really took off at the dawn of the 20th century when dedicated photographers were ironically forced to separate themselves from the technology that was propelling their medium forward into the future and into the mainstream, in an effort to slow down the photography of their time and essentially reverse its progress. They invented laborious homemade processes to manipulate their images and convey emotion and atmosphere – like a painting. They used special lenses and more complex, outdated cameras that no casual weekend “snap shooter” could possibly master.

Purists however, hated Pictorialism and still believe that image manipulation is against the rules. Charles Dickens simply gave up photography when the masses of weekend snap shooters invaded the realm that had been dominated by aristocratic gentlemen in the first forty years of its invention. Lewis Carrol, who excelled at the art, became a well-known gentleman-photographer and had his own studio, but he too quit when they introduced dry plate. Others were more dedicated and persistent when it came to staking their medium’s claim among the fine arts. Henry Peach Robinson and Peter Henry Emerson were among the pioneers of the movement that gathered a group of other likeminded photographers thanks to their early publications on the elements of pictorial photograph. The very concept of photo clubs was conceived with Pictorialism, spawned by a desire to associate with artists and their private salons and galleries.

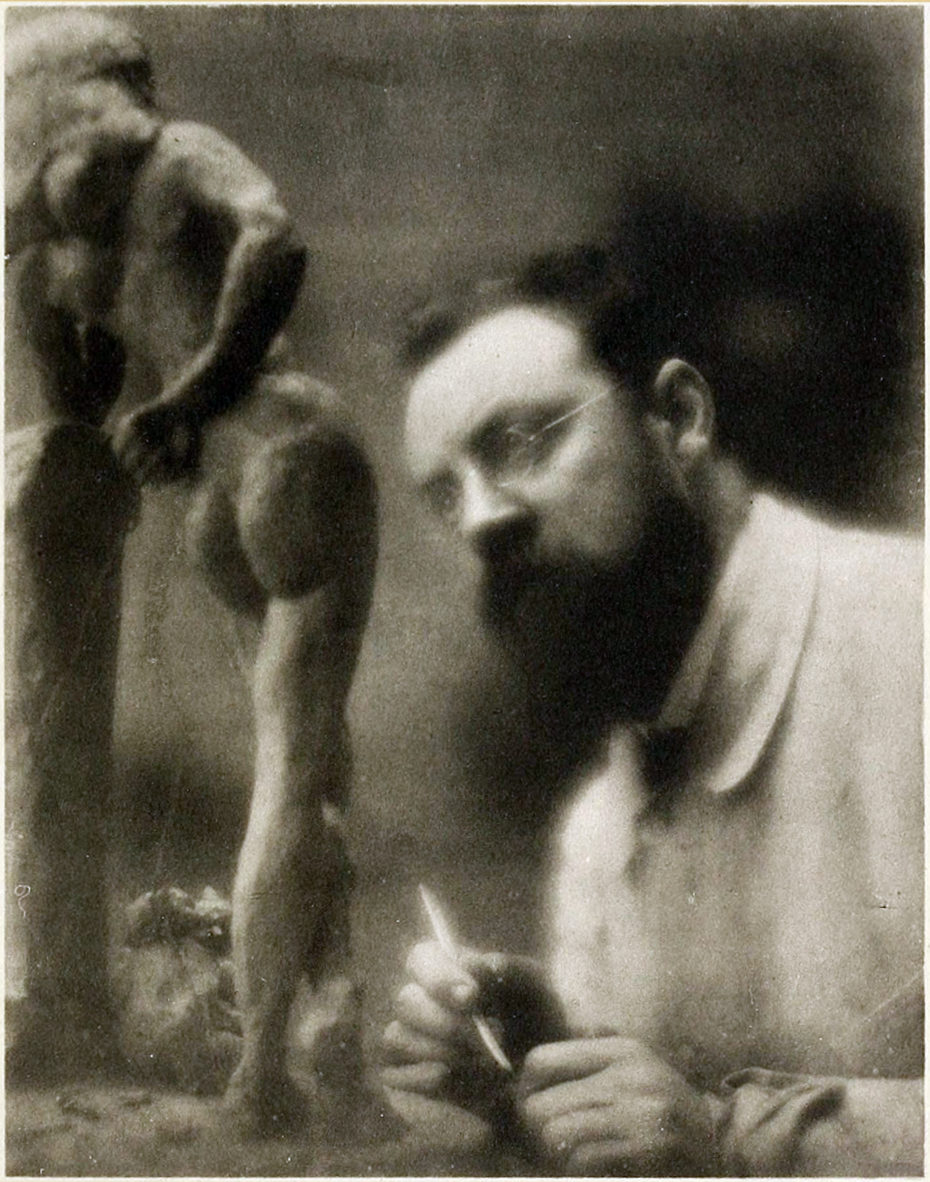

A good number of the movement’s photographers were in fact painters originally, who had adopted photography as a tool to help them record a model’s pose, or a landscape scene (everyone from Delacroix to Cézanne to Gaugin used photography for their work). Some of the finest prints created during the Pictorialist era are the most painterly; the ones that emphasise the physical properties of paint and how it’s applied across the canvas.

Such painterly effects were achieved with variety of labour-intensive processes, including the use of homemade emulsions, platinum prints and gum bichromate printing – techniques that emphasized the physicality of the light sensitive materials, created a soft impressionistic effect that paid homage to the painters who had come before them.

Pictorialists briefly embraced colour photography when it was first invented as early as 1903 by the Lumière Bros’. At first, they were fascinated by the results of the “Autochrome” process, but just as quickly rejected it because of its “pre-made” process and lack of hand control over the chemicals and techniques involved. Today, Autochrome is considered a dead art, left uncharted by 21st century technology and yet to be truly explored or recreated for the digital age. So much of what was produced using Autochrome plates however, is Pictorialism 101.

Pictorial photographers covered a broad array of subject matter, from domestic portraits, still lifes and nudes to landscape and architectural studies. But they didn’t always agree on the aesthetics of it and not all of it was very good. Peter Henry Emerson, who was all about honest documentation and natural landscapes, hated the work of his fellow pictorial pioneer, Henry Peach Robinson, who used costumed models in staged scenes. But they both agreed that photography could be regarded as a form high art. Despite the world of Pictorialism being led by a curious mélange of scientists, artists and academics, all Pictorialists certainly seemed to have one thing in common: nostalgia.

Pictorialists were modern, well-educated people, but when machines were “taking over the world” during the height of the Industrial Revolution, they yearned for the good old days and held on to the tradition of handmade craftsmanship. Many intentionally banned any hint of the modern, commercial and machine-driven world in their subject matter. However, later, as the movement evolved, some of the movement’s photographers started acknowledging industrialism and working with that factory-produced smog to create an eerie atmosphere, similar to how J. M. W. Turner did in his paintings.

But Pictorialism would be short-lived and the movement only really thrived between 1885 and 1915. When World War I broke out, the modern world had arrived. If you didn’t acknowledge machines and modernism, you were living in the dark ages. Public taste shifted, and it wanted sharp, focused images. Some of the most important Modernist photographers of the 20th century, such as Edward Weston, had began their careers in Pictorialism, but abandoned it like many others when went it fell out of fashion and effectively became a forgotten movement.

Will Pictorialism see a comeback? In the post-modern age, where liquid crystal displays are now a commonplace technology from mobile phone displays to wide screen televisions and sharpness becomes so common and ordinary, you could argue that Pictorialism’s renaissance is already underway. Such crystal clear sharpness in photographs where you can read every pore on the human face may very well feel grotesque to the art world in the near future, if it already doesn’t.

Jamie Beck is one of our favourite 21st century Pictorialists, who can recreate a Pre-Raphaelite-style image while still embracing and mastering digital photography. Meanwhile, collectors like Dennis Reed can be credited with reviving the forgotten movement, having recovered the lost work of an entire community of early 20th century photographic artists.

So how does one become a collector of fine art photography? First, train the eye. A good place to start would be the museums, art fairs and archives that have photography departments. Sir Elton John was, quote, “completely ignorant” about photography and today he possesses one of the most important collections of fine art photographs in existence today. Of course, he had a very different budget to the rest of us and his collection mainly centres around the modernist masters, but my point being, it’s never too late to start.

The next time you’re at the flea market or at your local auction house, turn your attention to fine art photography. Look out for the painterly photographs amongst a pile of antique prints. Check the internet for unknown early 20th century pictorialists whose $50 original signed prints could very well fetch thousands at an art gallery in the future. As technology continues to advance at lightening speed and history repeats itself, you might want to take a bet on Pictorialism.