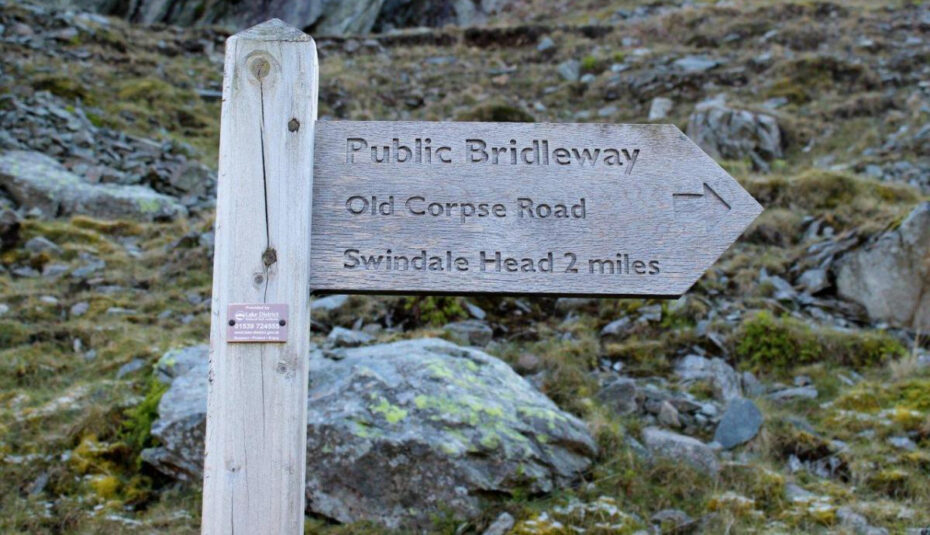

Walk with us, as we follow ancient trails where the living once carried the dead. We’ll be traversing Europe’s rural landscapes via a network of so-called “corpse roads”, occasionally marked with crucifixes and low stone benches, cutting across windswept hills, overgrown pastures, gushing rivers and rocky brooks. In Britain alone, 42 of these little-known funerary ways are documented in 19th-century Ordnance survey maps, literature, and memoirs, and those are just the ones we know about. Of course, when you have a network of roads trodden into the countryside just to transport the dead, folklore and legend will follow not far behind. Even in Shakespeare’s most magical story, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Puck pays homage to the corpse roads in his quote: “Now it is that time of night, that the graves all gaping wide, every one lets forth his sprite, in the church-way paths to glide.”

These remote corpse roads, also going by other morbid aliases such as coffin roads, bier ways, church ways, lych ways, or burial roads, may not lead to Rome, but rather they connect isolated communities to the main parish church cemetery.

Like all good stories, the corpse roads have their roots in power and money; in this case, we’re talking about the power and money concerning the local church. When these paths were etched into the rocky grounds of barren landscapes, churches wanted to make sure they kept their flocks in line – both those living and those dead – so when someone from their parish died, they had to be buried in the consecrated ground of the designated cemetery, which sometimes could be quite a literal trek from the deceased’s home. This meant the church got to keep the money that came with the parishioner’s burial rights, even if those who had died lived by the far borders of the parish. As communities expanded, some moved further and further away from the hub that was the parish church, which meant travelling miles just to bury the dead.

Since villagers generally didn’t want decomposing corpses carried past their front doors, these coffin roads traditionally cut across the parts of the land where no one wanted to go. Churches often had specially-allocated “death’s door” or Leper’s door for the passage of corpses. And naturally, since no one wanted the dead to come back to haunt the living, corpse roads also came with a few superstitious stipulations to safeguard against any unwanted supernatural activity.

Corpse roads often followed straight lines, the main reason for this being a practical one (taking the most direct route to the burial ground) but many also believed the spirits of the dead travelled in a straight line close to the earth. Something that ties in with this superstition is the sightings of the ominously named “corpse lights” or “corpse candles”.

These are mysterious lights or orbs running low to the ground said to have been spotted by passers-by on these burial roads. There are even legends that recount how these corpse lights would appear at the deceased’s house the night before they passed away, and then travel along the coffin road to the cemetery and disappear into the ground where the burial would later occur. Some said these lights were spirits of the dead trying to lead travellers astray, while others believed they were spirits of unbaptised children stuck in limbo between heaven and hell.

The next bit of corpse road housekeeping is the tradition that the body was always carried “feet first” in the direction of the cemetery to prevent the spirit from returning home. Other measures included the avoidance of obstructing the funerary path, so fences and buildings were not allowed to get in the way of transporting the body, but at some point, the road would have to cross some body of water. This latter measure arose from the belief that the spirits couldn’t cross water, so this was extra insurance to stop ghosts from returning to the community.

Crossroads were a tricky territory to navigate and harder to avoid (especially with all those straight lines). Not to mention there seems to be conflicting consensus about whether a coffin road intersecting with these was a good thing or not. Some considered it dangerous for a crossroad to meet a burial road, as they believed it would be an intersection between the world of the living and the underworld, and crossroads had the reputation of being a place where you could encounter the devil. Others thought it was a positive if a corpse road passed another road, as they believed crossroads had the power to bind spirits, which is why criminals often got hung at crossroads. Either way, some crossroads had crosses placed there to safeguard travellers from meeting the devil or being bothered by other troublesome spirits. “Witch balls” – a bottle or enclosed circle of glass containing threads and charms inside would sometimes be hung to catch and tangle passing spirits. Essentially, the living wanted to ensure at all costs that they would stop the dead in their tracks from wandering the land as lost souls or animated corpses.

Since coffin roads traversed the countryside, they would inevitably have to cross a few fields at some point too, and farmers were understandably less thrilled about it. Not only because many believed that any field used for a corpse road would ultimately be cursed and fail to produce good crops, but there was also some legal misunderstanding about the use of the land. There is a widely held, yet incorrect belief, that the passage of a coffin party across private land automatically turned that path into a legally-binding right of way. Although this law never actually existed, it perhaps arose from the agricultural practice of leaving a strip of unploughed land along the field’s edge wide enough for coffin bearers to walk abreast along the edge of the field that would be used for funeral ways to avoid contamination of the land.

If you were to hike some of these old corpse roads today (and many hiking trails follow these sombre paths), you might notice large stones along the route. These were called “coffin stones”. The flat bench-like stones served as a resting point for pallbearers, who could put the coffin down on the stones without cursing it by placing it directly on the ground. Coffins were usually made from wicker, which was much lighter and easier to transport than your traditional wooden coffin.

Although many believe coffin routes tend to be medieval in origin or even more recent, some clues show the tradition could even date back to Neolithic times. Archaeologists have found a few funerary routes in northern Europe that lead to Bronze Age burial grounds. In Britain, some burial mounds have been found to have neolithic earthen avenues, called cursuses, that run in straight lines connecting funerary sites – just like the corpse roads. In those days, you didn’t have the church or the need for consecrated burial grounds, so the reason behind their original pagan purpose is still a bit murky, but one possible explanation is they were used as a spirit-way function. Some may have even had stone rows lining them. There have also been archaeological findings in Somerset, where straight tracks made out of timber dating back some 4000 to 6000 years were found in bogs and likely used as causeways to transport to the dead.

This ancient tradition of using spirit ways thousands of years ago may explain the prevalence of another curious piece of folklore attached to this tradition: faeries – but not the fairytale kind. “A number of coffin paths across the country are linked to stories of faerie processions, sometimes described as faerie funerals or as faerie troops heading into battle,” explains Esmerelda’s Cumbrian History & Folklore. “In Ireland in particular, houses that intersected old coffin routes were believed to suffer bad luck as a result of faery wrath.; ancient spirits of the dead. We find it difficult to make the link, but many a faery tradition makes perfect sense when you substitute the faeries with ghosts.”

If we look back to Shakespeare again, Puck’s quote leaves little doubt that these coffin routes were perceived as spirit routes for centuries, and their legends still prevail in folklore even to these days. Whether you think of ghosts, spirits of the dead, faeries, sprites, or will-o’-the-wisps, the supernatural seems to haunt the corpse roads wherever you go. So the next time you’re out for a wander in the olde country, keep an eye out for the clues. Some of the most interesting and beautiful routes include:

- Ambleside to Grasmere, Cumbria

- Black Mountain, Carmarthenshire

- Lych Way, Devon

- Coffin Route, Outer Hebrides

- Buttermere Corpse Road, Cumbria

- Kintail, Highland

- Garrigill to Cross Fell, Cumbria

- Swaledale Corpse Way, North Yorkshire