“What works good is better than what looks good, because what works good lasts,” once said Ray Eames, the artist, designer, and wife of Charles Eames. The Eames partnership revolutionised our concept of modern furniture and quite literally shaped the way we live. Although their collaboration was truly egalitarian, Charles Eames became the face behind the household name, while his wife Ray’s legacy was tucked away behind her husband’s shadow. “Anything I can do, Ray can do better,” Charles had said, who frequently acknowledged his wife as his equal partner in his business and credited her as the brains behind many of their designs. Still, design history didn’t leave much room for a woman in the picture.

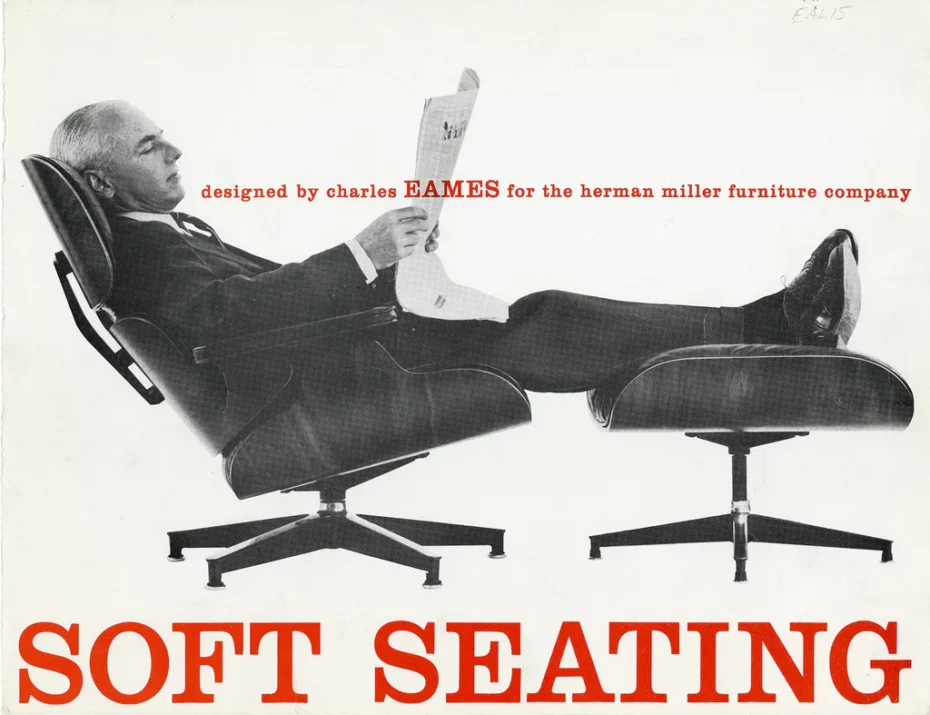

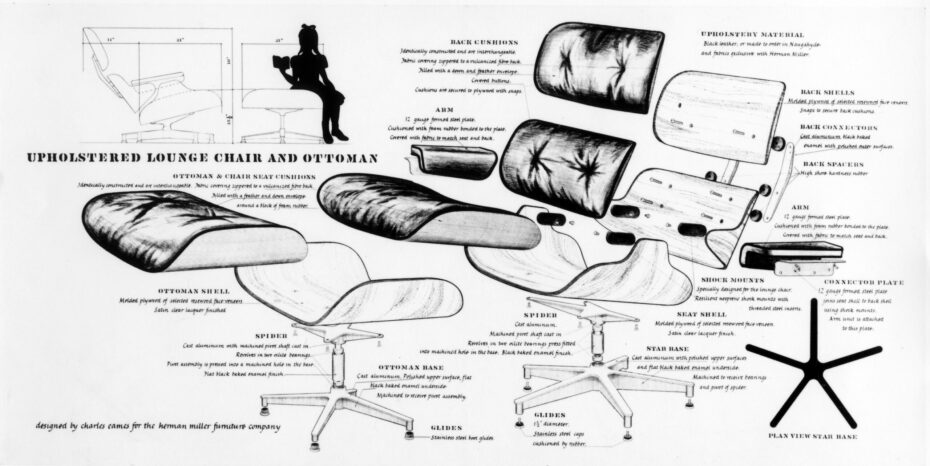

By moulding plywood with their magical “Kazam! Machine”, the design power couple introduced the world to the iconic Eames Lounge Chair and the Eames Dining Chair, and contributed heavily to graphic design, fine art, and film. The Eames even impacted modern medicine with their invention of plywood splints, replacing the metal traction splints that caused gangrene due to impaired blood circulation.

Although she would make her name in design, Ray took a different path towards abstract art in her early career, mainly as she followed her early passions for art and ballet. She studied illustration, poster art, and art history at the local Sacramento Junior College in the early 1930s before she moved to New York to study with European emigré artist Hans Hofmann, one of the key players in the transformation of European abstraction in American art. Hofmann had an excellent way of using abstract form, colour, and composition to create illusions of depth, space and movement, most notably his “pull and pull” technique that created tensions in his art, which clearly inspired Ray Eames later in life.

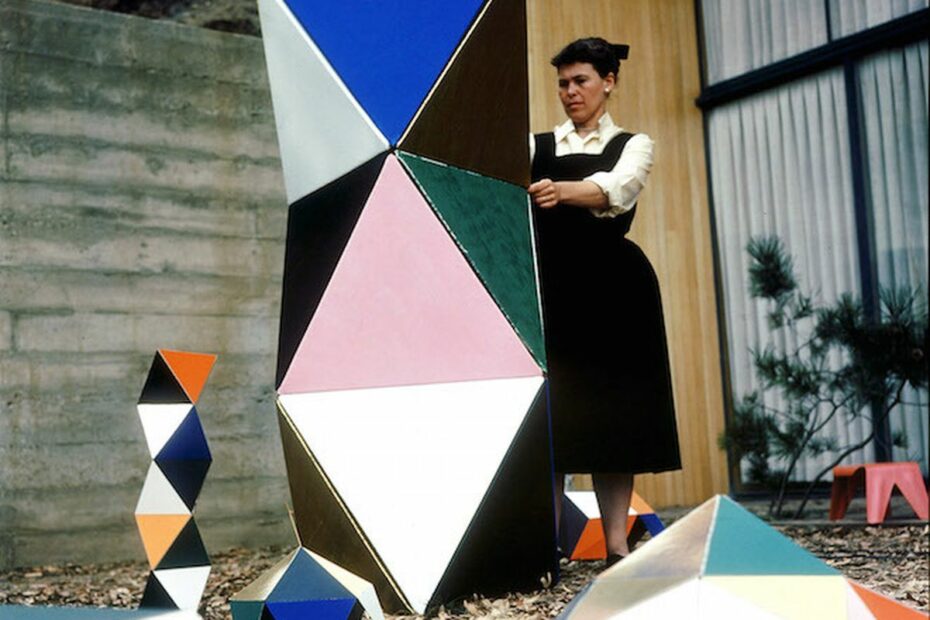

In New York, she exhibited her paintings and became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group. She blossomed in the New York art scene as she hobnobbed with the likes of Lee Krasner and Mercedes Matter, critical figures in the abstract expressionist movement. Maybe Ray would have become a celebrated abstract artist in another life, but she had to abandon her New York life when she was called to the bedside of her ailing mother. Although Ray left the art world, she always carried her love of shapes, structure, and colour into her designs in the decades to come. In fact, she’d deny she left art and once said, “I never gave up painting, I just changed my palette.”

Ray wanted to develop a career beyond art and was fascinated with structure and architecture. She even considered going into engineering at one point. Or, at the very least, Ray wanted to build a house. But upon the recommendation of an architect friend, she instead enrolled at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan following her mother’s death in 1940. This decision would be a life-changing one for Ray, as she’d not only move beyond painting at Cranbrook, but she’d also meet Charles Eames, the head of the department of industrial design at the academy. Although Charles was married, he divorced his first wife in 1941 and married Ray shortly after, and they moved to Los Angeles.

Even before the Eames invented their iconic plywood furniture in the early 1940s, Ray was already experimenting with the technique as she was creating biomorphic-formed sculptures out of bent plywood. Just look at her sculptures; it’s easy to see they were prototypes for their furniture, even if the famous Eames chairs would only be developed a few years later. Her sculptures allowed the Eames to tinker with the techniques of bending and shaping pieces of laminated plywood into these complex curves.

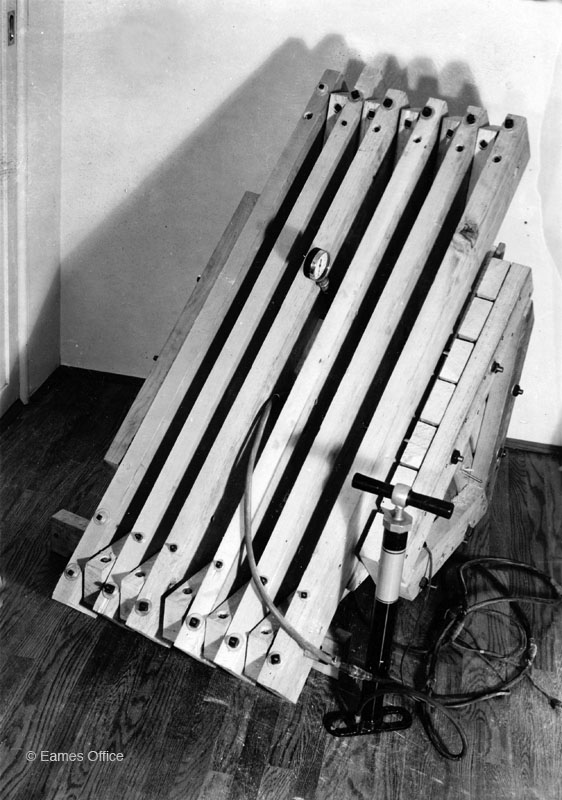

We can thank Ray for the technique. When the couple moved to Los Angeles in 1941, Charles got a job at MGM as a set designer, so Ray was left to her own devices at home and set up the prototyping process to make their early designs a reality. Being based in LA gave them a unique advantage, as they were close to the aircraft industry, so Ray found it easy to get her hands on the perfect materials they could use for constructing plaster moulds that would eventually be used for chairs and splints.

These early experiments with plywood would eventually lead to the invention of the Eames “Kazam! Machine”, a kind of a magical machine that worked by placing a sheet of veneer into the machine mould, and then a layer of glue was added on top.

This process was repeated five to eleven times, and using a bicycle pump, they would inflate a rubber balloon once the machine was shut, pushing the wood against the form. Once the glue was set, the Eames released the pressure and removed the moulded plywood from the mould. They would then use a handsaw to finalise the shape and smooth the edges down, sanding by hand.

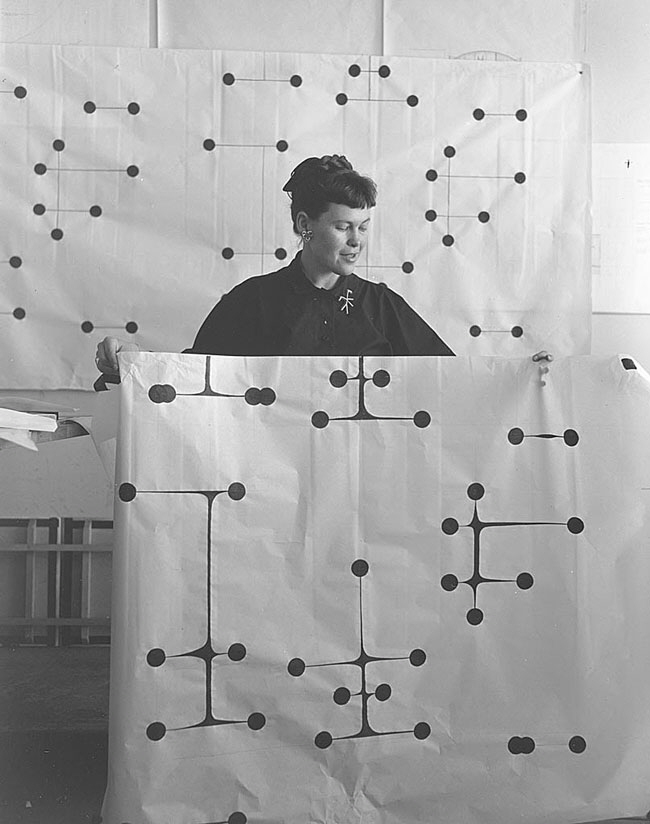

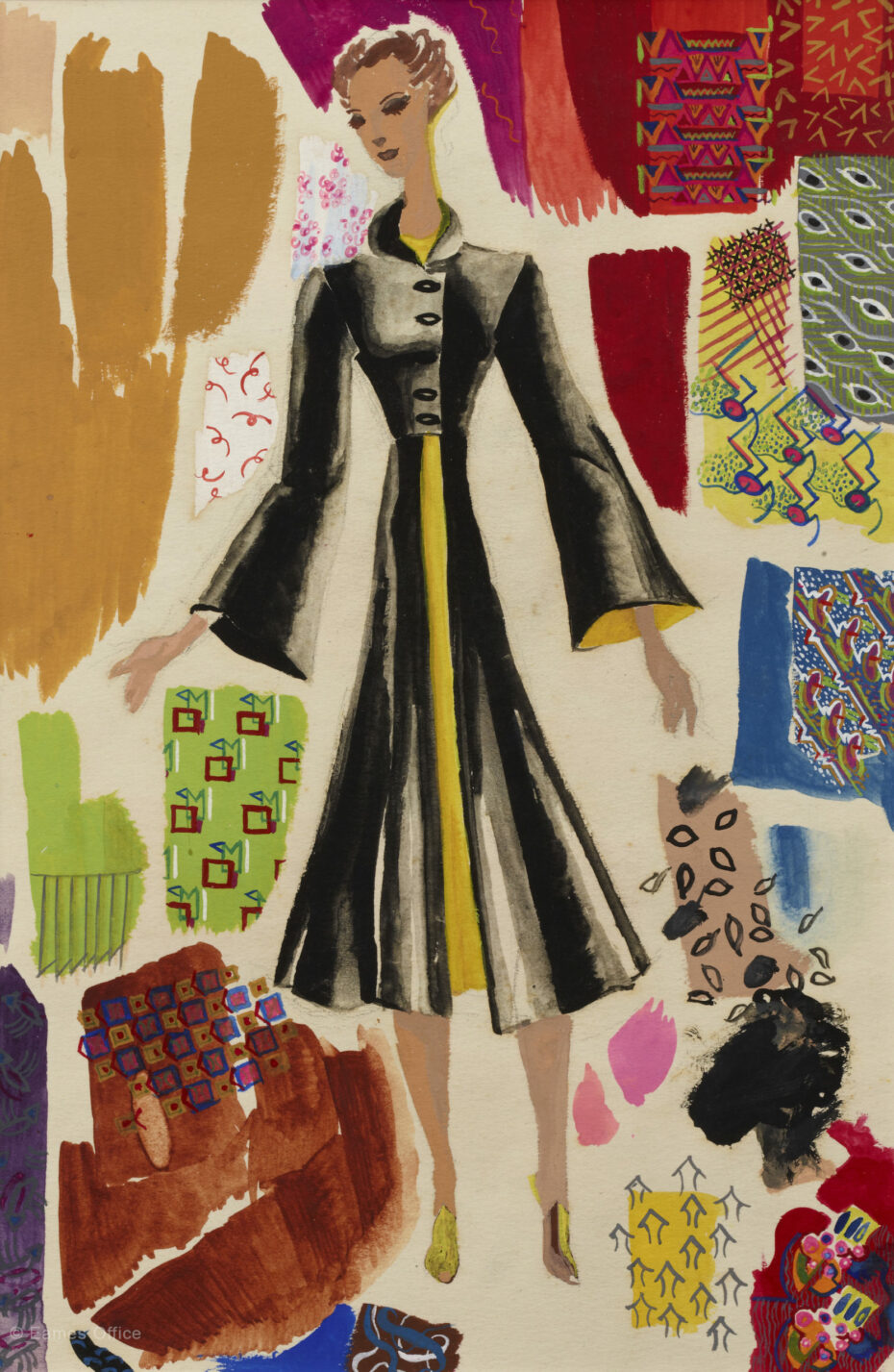

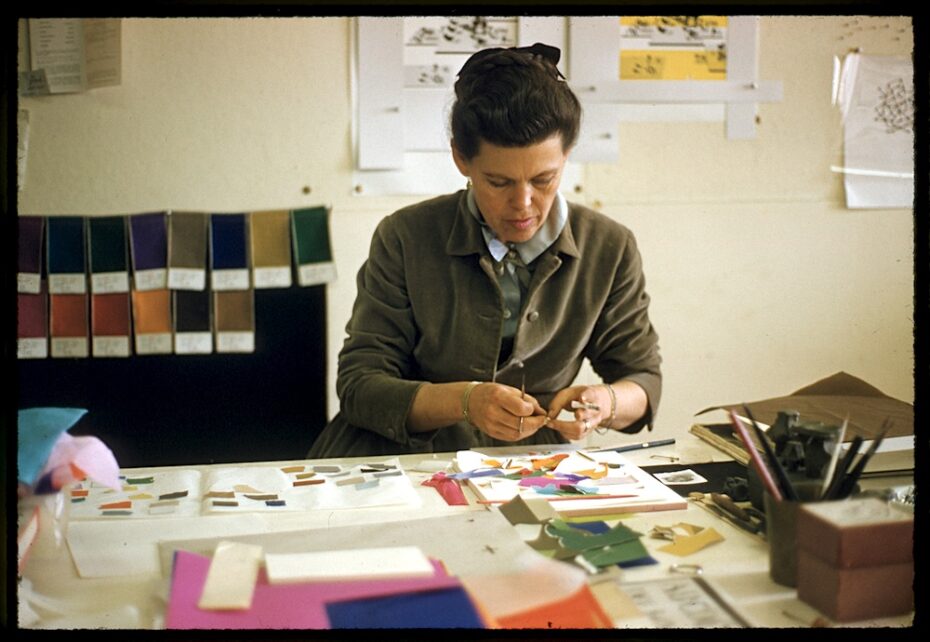

That’s not all Ray Eames did; she also turned her hand to graphic design and textiles. She did the former in the Eames Office, and we can thank her for the aesthetic style of the Eames branding. She also designed 27 covers for the journal Art & Architecture between 1942 and 1948.

In 1947, Ray created several bold geometric textile designs, the most notable being the “Cross Patch” and “Sea Things.” Many of her designs are still in production with Maharam almost 70 years later. She won awards for two of her patterns in a competition organised by MoMA, and you can still find some of her textiles in various art museum collections.

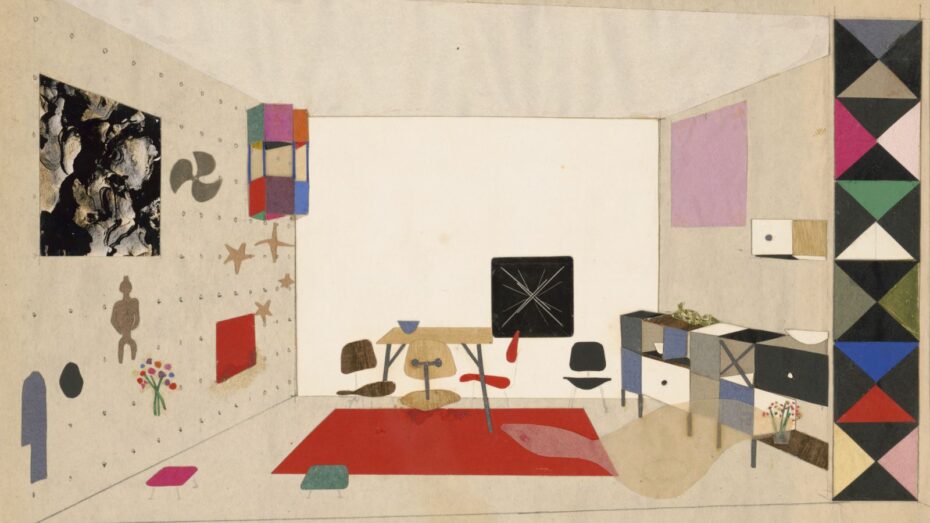

Ray and Charles would delve into architecture at the end of the 1940s when a challenge was proposed to the architectural community to create a series of homes that would express life in the modern world. The mission was to build and furnish these houses with materials and techniques derived from the experiences of World War II. They would be case study houses, and Case Study House #8 would be for a married couple working in design and graphic arts with no children living with them, so of course, Ray and Charles seemed like a good fit. They built their house, a two-storey structure that would accommodate a studio and a residence, and incorporated a design that would not destroy the meadow surrounding it but instead “maximize volume from minimal material.”

Their modular home was finished by December, and the Eames moved into Case Study House #8 on Christmas Eve 1949 and would stay there for the rest of their lives. It would be their base where they would create furniture, experiment with new technologies like fibreglass and resin, live, and play.

Of course, this ultra-modern couple also explored the medium of film from 1950 to 1977 to explore their interests, like the relative scale of the universe, the beauty of soap suds, collecting toys, and exhibiting their work.

Ray had a passionate love for the little things, quite literally. She collected curious and delightful objects throughout her life, like those left behind after film shoots, sugar figures made for Mexican altars, shells, balls of yarn, Chinese kites, combs, and even charmingly wrapped (yet unwrapped presents). She collected these items and made artistic arrangements that wouldn’t be out of place in a Wes Anderson film.

Ray’s love for small objects would go on to usher in an interior design trend. Architect Charles Moore said that Ray “single-handedly brought about a return to richness, the joy of the miniature object in a modern framework.”

She was known for her attention to detail, which is why you’d never want to get in a car with her. Ray was so drawn to anything visual she paid attention to everything but the road while driving, hence her husband’s refusal to ride in the car with her (luckily, Ray lived a long life and, amazingly, as far as we know never crashed her car). She died in 1988, ten years to the day after Charles passed away. She didn’t even leave their funerary details to chance, and she designed the pine boxes that would house her and Charles’s ashes. She made them out of straight-grain sugar pine, force-fitted lids, and had them lined with handmade Japanese paper embedded with flowers and leaves. Ray was buried next to her husband in the same grave in St. Louis. It’s hard to separate Ray and Charles’s creations, as they were a true partnership and created everything together. The office of Charles and Ray Eames operated from 1943 to 1988 until Ray passed away. Ray Eames was one of the design icons of the 20th century, but we think she could use a bigger page in history.