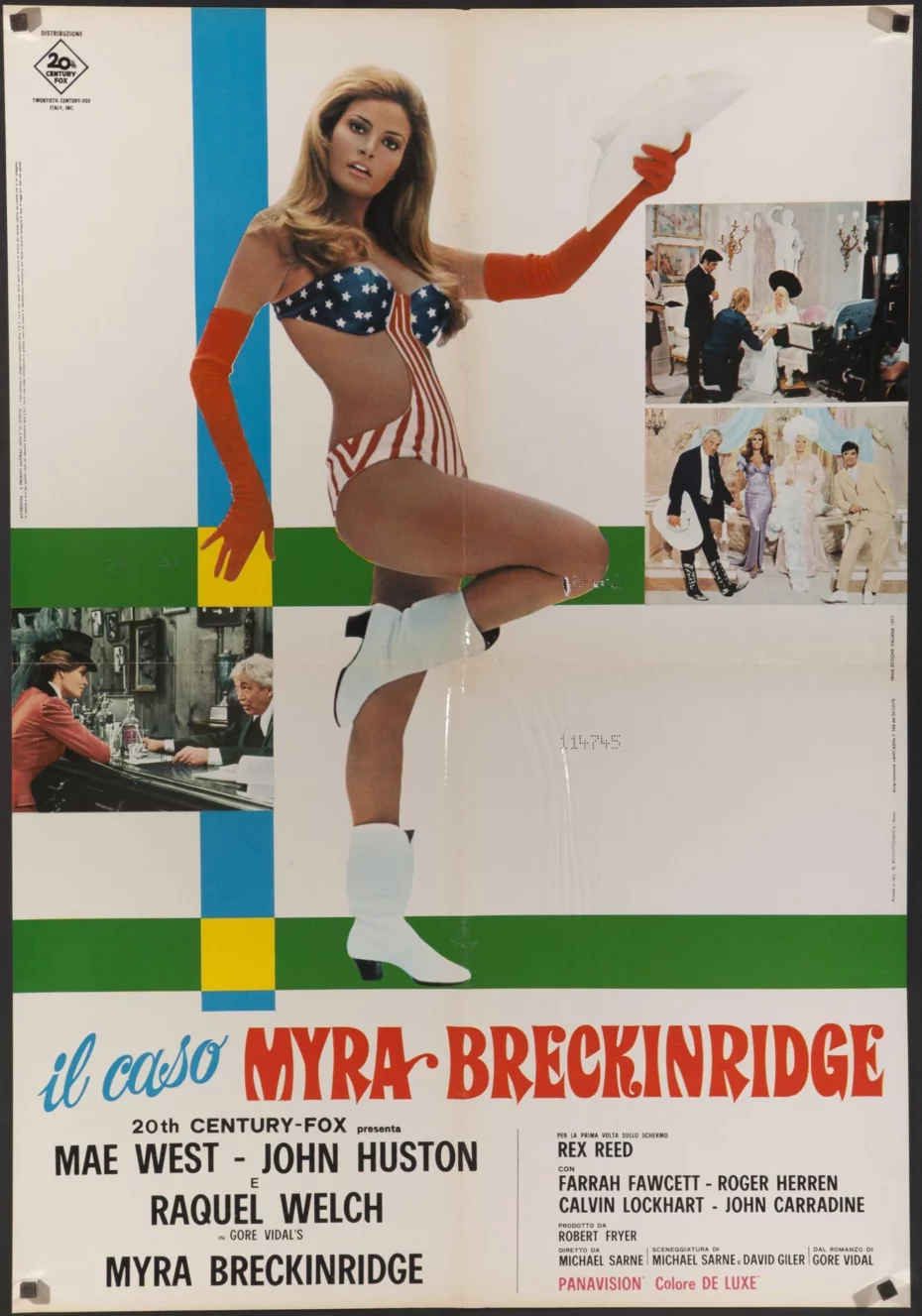

At first glance, the surreal plot of what has been called “one of the worst films ever made” seems like a reiteration of harmful tropes: an ambitious transgender woman cons her way into a position of power and ultimately uses it in an attempt to destroy gender norms (in a nutshell). But believe it or not, the 1970 comedy Myra Breckenridge starring Raquel Welch, Mae West, and a then-unknown Farrah Fawcett and Tom Selleck, was revolutionary in its portrayal of transgender identity; the first big-budget Hollywood movie ever to depict a leading transsexual character. And maybe, just maybe, amidst the current boom of Hollywood reboots, this is one story deserving of a 21st-century comeback. Just not in the way you might think. So hear us out.

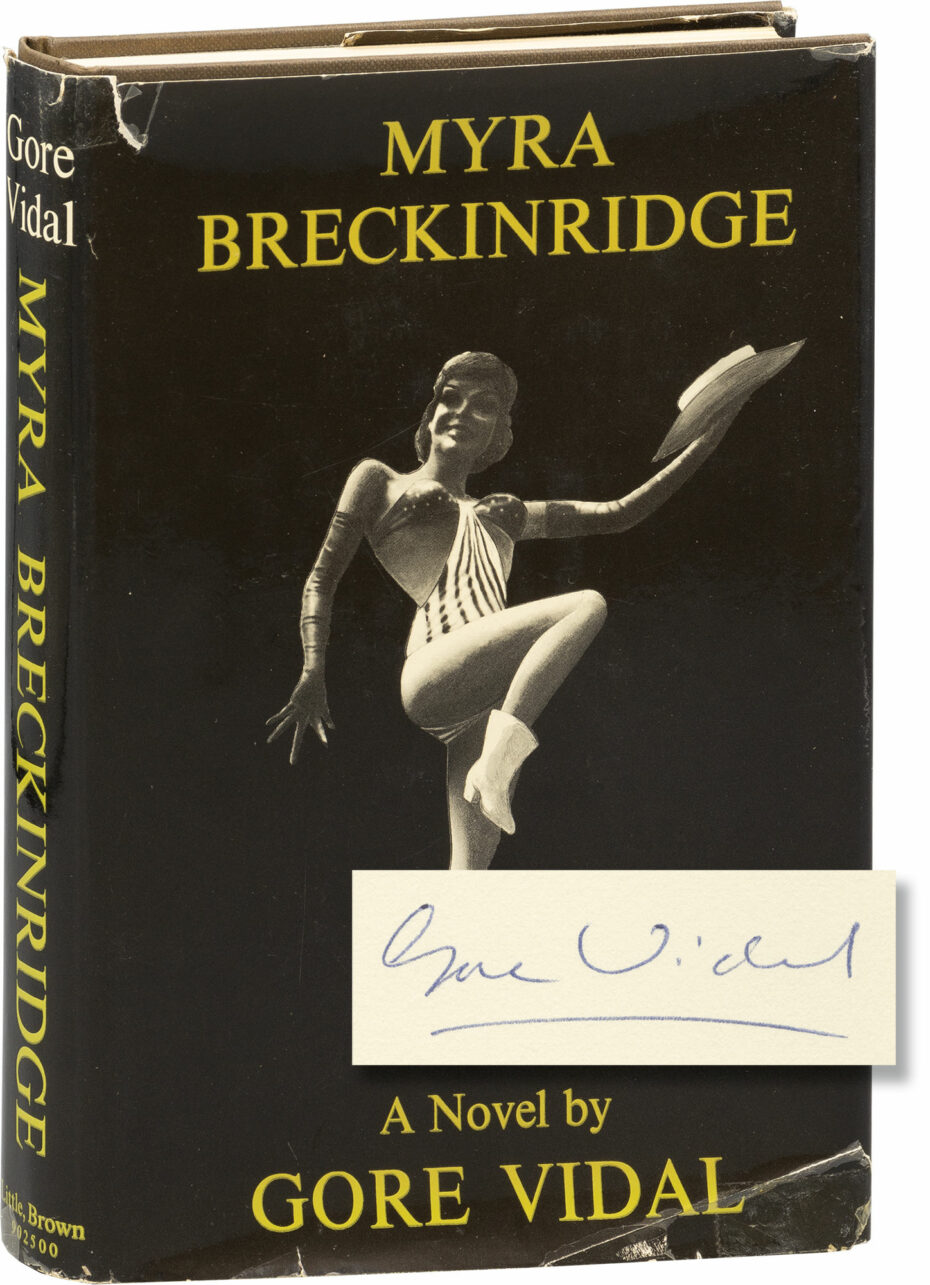

Myra Breckenridge is based on a 1968 novel of the same name by Gore Vidal, a queer writer and aspiring politician who openly explored sexual themes in his work. The satirical book, the first to ever feature a clinical sex change, was both an instant bestseller and critically acclaimed as a classic in many circles. Twentieth Century Fox paid Vidal a remarkable $900,000 for the rights.

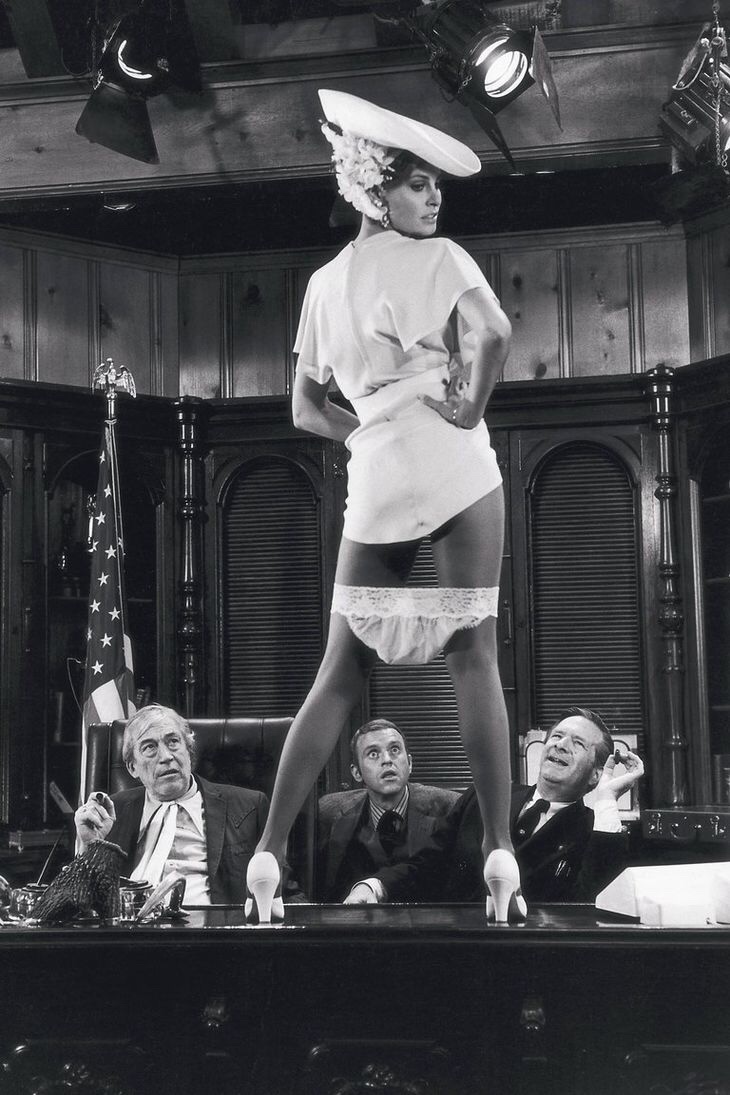

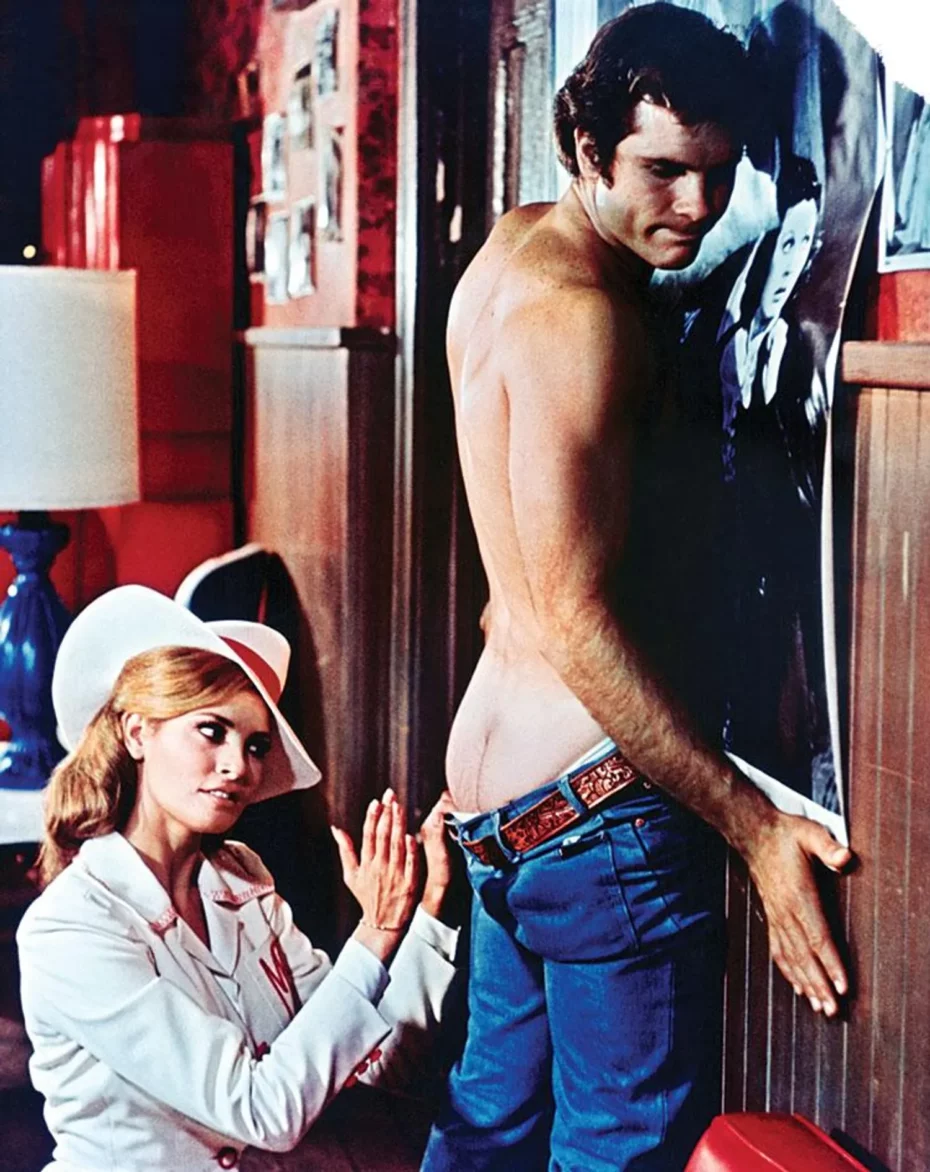

The story begins with Myron Breckenridge, a gay film critic, flying to Copenhagen for a sex-change operation to become the beautiful anti-hero, Myra – enter Raquel Welch. As a woman, she then shows up in Hollywood pretending to be the widow of Myron and lays claim to half of his uncle’s fortune, a respected acting school in Westwood, California. Uncle Buck settles on letting Myra teach there but also secretly begins investigating her. While teaching an etiquette class, she switches up the curriculum to deconstruct the social order and introduce her students to the concept of femdom, the practice of female domination in BDSM activities. Her character ultimately reveals that her mission is to destroy “the last vestigial traces of traditional manhood in the race in order to realign the sexes, thus reducing population while increasing human happiness and preparing for its next stage.” But in a surreal, Tarantino-style “revenge fantasy” twist (warning: sensitive material ahead), the most controversial plot point sees Myra, dressed in a Stars and Stripes bikini, rape one of her male students with a sex toy before seducing his girlfriend (played by Farrah Fawcett). It was the first time the world had seen anything like it from a major Hollywood studio, and Twentieth Century Fox trailers teased the scene as “the most sensational scene in the history of the screen’’.

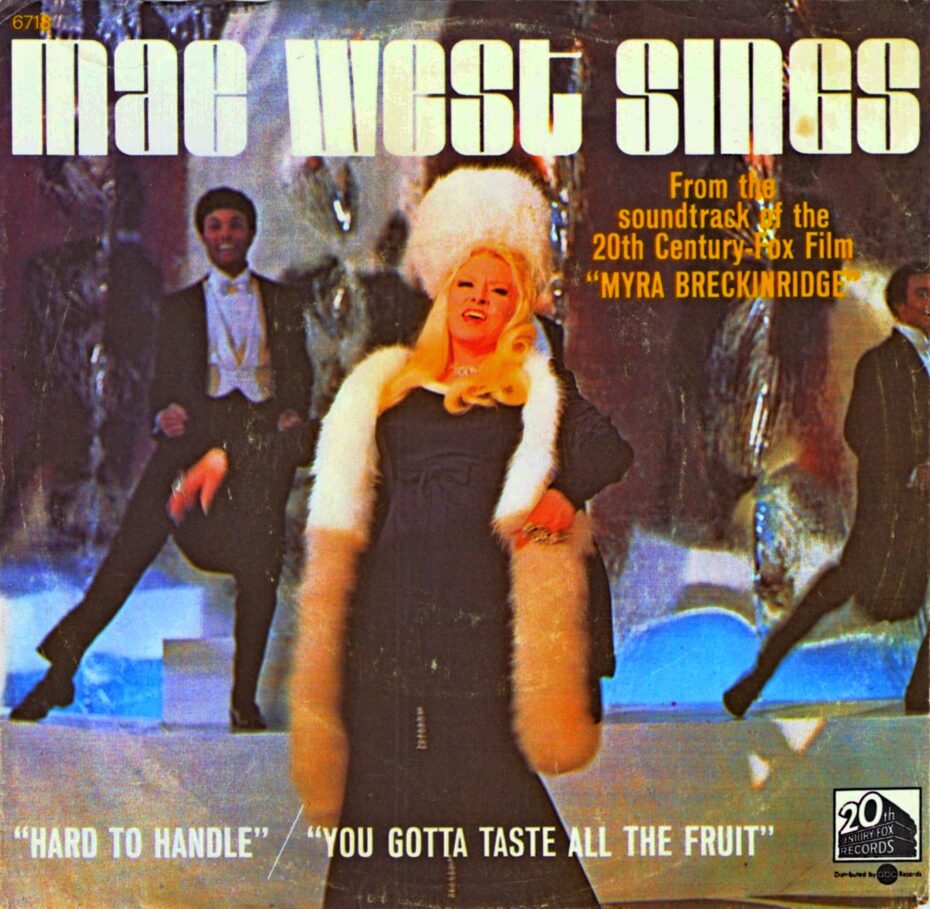

She isn’t the only female character who abuses her power. Mae West, who came out of a 27-year retirement to be in the film, plays Leticia Van Allen, a female casting agent who seduces the much younger men who audition for her, including Tom Selleck. For her part, West was paid a whopping $350,000, was allowed to write her own lines and arguably steals the show with her sensationally camp musical numbers.

Spoilers ahead: Buck is able to find out about Myra’s true identity, at which point she strips naked to reveal to him that she still has male genitalia. An apparition of Myron (Myra’s male alter-ego, who reappears in visions throughout the film), eventually runs Myra down in car, believing she has become too ambitious. In the Wizard of Oz-esque ending, Myron reawakens in the same hospital back in Copenhagen, and discovers no gender reassignment has taken place, but he has been in a car accident. Myron looks over to see a magazine on his bedside table with a photograph of actress Raquel Welch on the cover. It was all a dream.

Upon its release, the picture was universally bombed by critics. Variety wrote that it “plunges straight downhill under the weight of artless direction” and Time Magazine said it “was as funny as a child molester.” It has been included on many “worst films of all time” lists, and many lamented how it had ruined what was a clever and innovative novel. Even Vidal disowned the movie as “an awful joke” despite having written the original screenplay before it was scrapped for another version. Myra Breckenridge the book is littered with transphobic, homophobic and sexist innuendos which Gore Vidal had written satirically but were lost in translation on film. “It just really didn’t do Vidal’s book justice,” Raquel Welch remarked in an interview 45 years later, and admitted to the same magazine that the film eliminated a deeper analysis of the trans experience. At the time of filming, she was under contract at Fox. “I didn’t feel that the script was leading anywhere. It didn’t really have a narrative. It was just impressions, a transgender fantasy or something.”

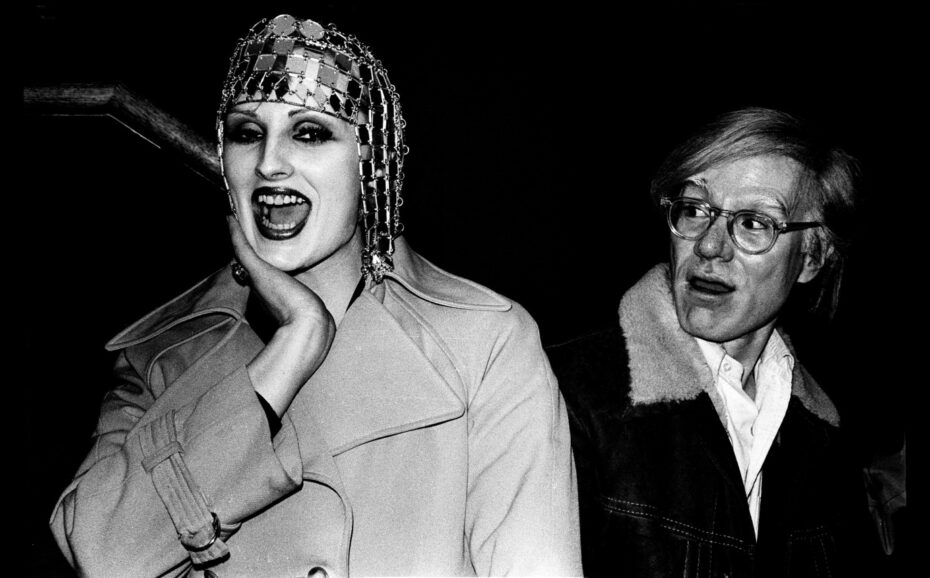

The movie adaption was directed by Mike Sarne, who was given complete control over the project, but after Myra Breckenridge, he never directed another film with an American studio again. The producers did initially try to cast a transgender actor as Myra, and several auditioned, including Andy Warhol muse Candy Darling. Before Welch won the role, other notable cisgender stars allegedly turned down the role such as Audrey Hepburn and Vanessa Redgrave. Elizabeth Taylor and Angela Lansbury were also reportedly in the running.

In Andy Warhol’s memoir, he wrote about the studio’s decision to pass on Darling, a pioneering trans woman who was discovered by his factory in 1967: “Candy suffered a big disappointment in ’69. In fact, she never got over it. As soon as the news that a movie of Myra Breckinridge was going to be made appeared in the trade papers, Candy began writing letters to the studio and the producers and whoever else she could think of, telling them that she’d lived the complete life of Myra … It was true. And they gave the part to Raquel Welch. Poor Candy wrote begging them to please, please reconsider. She knew that if there was ever going to be a role in Hollywood, for a drag queen, this was it.”

Several members of the cast have since discussed how dysfunctional of a set it was and how conflicting visions for the film resulted in the disjointed final product. Mae West called out “the inexperience” of director Mike Sarne, who in turn referred to her as an “Old Raccoon.” Farrah Fawcett, then unknown, supposedly hid in her dressing room, crying and scared to come out, notably because of the conflict between West and Welch.

In her 2015 interview with Out, Welch said, “I didn’t know what to think about [Mae] at the time […] I only knew her camp performance and I was thinking I might meet the real-life person, but that never happened. I don’t know if she had a real-life person in there […] I guess Mae wanted me to carry her train and maybe crawl behind her in homage.”

Welch also butted heads with co-star Rex Reed who played her alter-ego, Myron. Decades later, the backstage bickering appeared to be still very much in play when Out magazine caught up with the cast in 2015.

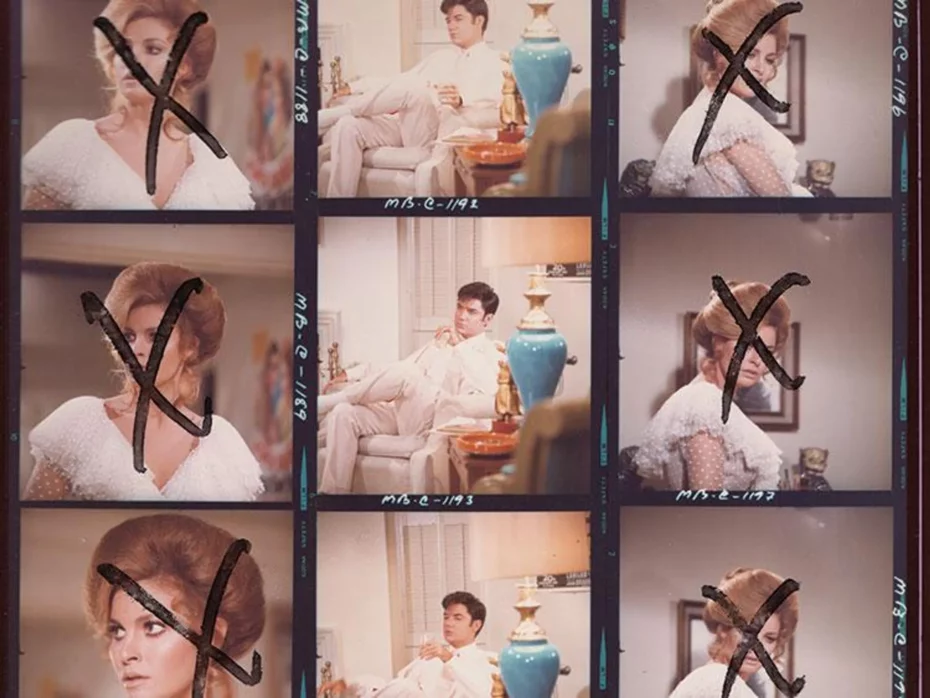

“Raquel was so mean to her. She treated her like a mule!,” said Reed giving his account on the lead actress’ relationship with Farah Fawcett. “Raquel really made things difficult for herself. She’s a very insecure actress. I’d get contact sheets back, and she’d crossed out any photo where I looked great”.

The many classic films referenced in Myra Breckenridge also caused a political storm. The film style stands out, for better or worse, with its usage of scenes from classic movies interspersed heavily throughout the narrative. The White House asked for the footage from 1937’s Heidi, featuring Shirley Temple, to be removed, given that she was serving as a US ambassador. As actor Rex Reed recalled, “This was a film where the lawsuits really flew”.

It was also a difficult balancing act for the stars promoting the film, especially for Welch, who faced criticism for being recognised just for her looks. (She was then most famous for a poster of her from the 1966 film One Million Years B.C., in which she wore a doe-skin bikini.) Raquel Welch also later disowned the film.

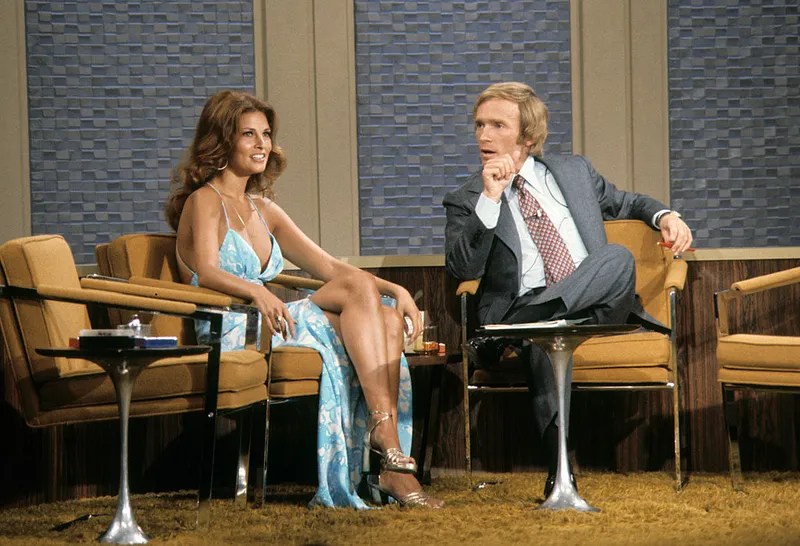

In a 1970 interview on The Dick Cavett Show, with Janis Joplin also on stage, Welch noted that the majority of the audiences she saw watching the film were homosexual, a subtle acknowledgment of who recognised themselves in the narrative. She noted the mixed reaction from critics — from “disgusting” to “novel” — and said herself, ”it’s going to be treated importantly. It’s not going to be dismissed.” As for Joplin, she diplomatically noted that she found all the quick cuts to be “too choppy. I couldn’t understand it. It kept changing all the time.”

Over 50 years later, it’s hard not to grimace at much of Myra Breckinridge, but it has merit as a relic of its sociopolitical era and has since gained a small cult following. The end of the free-loving 1960s included a backlash against the progressivism of the anti-war movement, civil rights protests and third-wave feminism. At a time when the rise of Richard Nixon and the modern American conservative movement were gaining a base around supposed traditional family values, the film laughed in the face of all that was considered normal and proper — did we mention the movie also has an orgy scene? It wasn’t the only transgressive response to neo-conservatism at the time; Beyond the Valley of The Dolls, the other R-rated film that 20th Century Fox released in 1970, went on to become a cult classic, itself a parody of the critically derided Valley of the Dolls.

In the book and film, Myra describes young men as “quite totalitarian-minded, even for Americans, and I am convinced that any attractive television personality who wanted to become our dictator would have their full support.” (Talk about foresight).

It’s perhaps no surprise that influential American conservative writer William F. Buckley seized on the film’s source novel as “an exemplar of the perceived collapsing mora ls of the left,” as Mark Athitakis wrote in a 50th-anniversary article. Buckley in fact took part in a series of heated debates with author Gore Vidal during the contemptuous presidential nomination conventions of 1968, a year marked by mass civil unrest. Buckley called him a “crypto-Nazi” and told him to “go back to your pornography.” For Vidal’s part, he would return to the characters of Myra Breckenridge with the 1974 novel Myron, set in 1940s Hollywood.

As the first major Hollywood picture ever to depict a transsexual character, albeit in all the wrong ways, Myra Breckinridge was an important moment in history. One can only imagine the enormous potential of a more nuanced version of Myra Breckinridge, re-examining the real experiences of transgender people and how queer stories are told in the entertainment landscape. Here’s what we’re thinking: instead of yet another Hollywood remake, perhaps the most powerful story would be a behind-the-scenes one. In the same way Michael Tolkin’s fantastic Paramount miniseries The Offer (2022) followed the chaotic making of Francis Ford Coppola’s highly-praised gangster film, The Godfather – what if this behind-the-scenes formula could be used to revisit “the worst film ever made”? Alternatively, there’s ample material for the gender identity debate to be explored in Gore Vidal’s little-known and even whackier follow-up, in which the lead character’s recently reconstructed male version and the anti-hero Myra, fight for control over their body. Let the fantasy casting begin.